Let’s face it. As improvising musicians, we’ve become obsessed with notes. Obsessed with harmony, chords, and scales. Which scales to use over which chord progressions, which diminished scales to play over dominant chords, how to play “outside,” how to play “inside,” which chords can be substituted for others…We even reduce entire sounds, full of infinite sonorities, down to measly scales: “Oh, G7 #9, you just gotta play an altered scale, works every time!”

Even when we get on the right track and begin to transcribe solos from our favorite records, it can be easy to forget that we’re looking for more than just the notes. It’s through this process of imitation that we absorb the styles of our heroes and begin to create our own sound, but this involves much more than simply determining the pitches in a solo or conducting a theoretical analysis.

Looking beyond the notes

Countless transcription books have reduced entire solos down to mere shadows of what the recording presents. The actual pitches of the solo are only one piece of the valuable information available on the record. You can get the notes from the page, but what about the articulation, time, tone, touch, volume, accents, feel, idiomatic effects, or other “intangibles” of the solo that can’t be represented in print?

It’s hidden within these intangibles that you’ll find the true musicality of the solo. The subtle aspects of expression that make it personal, intriguing, and emotional. The daring excitement of Elvin, McCoy and Jimmy Garrison playing behind Trane, the swagger in Lee Morgan’s sound, the warmth and joy emanating from Clifford’s bell, the eye-opening effect of Miles and Wayne playing over Herbie’s comping – these are the real reasons that we listen to music.

If you reduce all these aspects to just the notes, what’s the point of listening?

This would be like a chef trying to recreate a famous dish and only copying the basic components – the ingredients – to recreate the dish. The aspiring chef has the building blocks of the dish, however, the true essence of the dish comes in the preparation and presentation.

Anyone can look at a recipe to find the ingredients, but it takes years of practice to turn those pieces into a fully realized meal. In the end, it’s the technique of preparation, the personalization that comes with experience, and the subtleties of flavor that make it unique.

What’s missing from transcription books

We’ve all encountered books of transcribed solos or purchased them at one time or another. Why not? You can get all the notes and secrets of the greats just by looking at a page, right? The only problem is that these books don’t work. No matter how easy or logical it seems, you just can’t learn to improvise by reading from a page.

The true benefit of transcription comes from doing the transcription yourself. In order to study the great voices in jazz and eventually create your own concept, we must learn directly from the records.

The great trumpet player Clark Terry has that much sought-after quality of many master musicians: the ability to create musical expression and convey personality with just one note. After listening to a single note, you can tell immediately that it’s Clark Terry’s unique voice on the trumpet..but can this be reflected on paper?

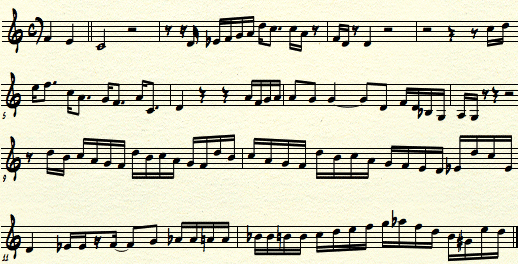

Take a look below at the opening 12 bars to his solo on One Foot in the Gutter from the album In Orbit. Just by looking at the notes, how would you play this excerpt?:

Now, keeping your interpretation in mind, listen to how this truly sounds (solo begins at 1:19):

As you can see from the example above, the best you can do with a written representation of a solo is a well-intentioned approximation. You can write down the notes, try for the rhythm, figure out the scales and chords, and come up with a concept based solely on music theory, but these are all meaningless without the recording.

But what about reading a transcribed solo along with the recording?

While you can approximate the style of the solo because the notes are right in front of you, the primary mistake, is that you’re leaving your ears totally out of the equation. By reading the notes, you aren’t hearing the intervals of the solo, figuring out the chord progressions, or internalizing how the lines relate to the changes. You can imitate the style of the solo you’re reading from a piece of paper as you play along with a record, but when you try to create your own solo, you’ll find yourself hitting a wall.

Transcribing everything

The first step to getting more out of the transcription process, is to transcribe absolutely every aspect of the solo. Get away from the habit of transcription that goes directly from the record to the paper note by note – the only goal being to get the pitches. Yes, when you’re finished you’ll have all the notes on a page to look at, but how much is that going to benefit your playing?

Instead, take one phrase at a time. Listen for tone quality, the time and the overall feel of the soloist. Emulate every articulation, every accent, even every breath. A quick way to absorb all of these subtle details is to sing it before you figure it out on your instrument. By singing the phrase, you’ll naturally imitate the tone, articulation, time, and volume with your voice. As you learn the solo in this fashion, the nuances of musicality will be automatically ingrained into your playing.

Getting past technique and theory

Of course you need to understand harmony and the particulars of music theory, but this alone is not a means to an end. We must curb our obsession with notes long enough to explore the other valuable aspects of musical expression, things like: How to make a musical statement, how to develop a phrase, the tonal varieties inherent within our own instruments and subsequently within ourselves.

In an academic setting, you can teach which notes work over a chord and what scales are theoretically “correct”, but you cannot teach expression. This must come from imitation and serious study – total immersion in the records. Excellent technique and theoretical knowledge are necessary, but they’re no substitute for musicality. The nuances of expression and emotion in music are what truly create meaning for the listener.

It is a widely accepted notion among painters that it does not matter what one paints as long as it is well painted. This is the essence of academicism. There is no such thing as good painting about nothing.~Mark Rothko