Becoming fluent with jazz language is the key to unlocking your musical freedom when you improvise. It’s the missing piece of the puzzle. The lost ship. The thing everyone ignores…

And it’s totally counter-intuitive…

- You copy, to sound original.

- You practice the same line over and over, to be creative.

- You use limitation, to find freedom.

If you’re already confused, that’s okay. We’ll get there…

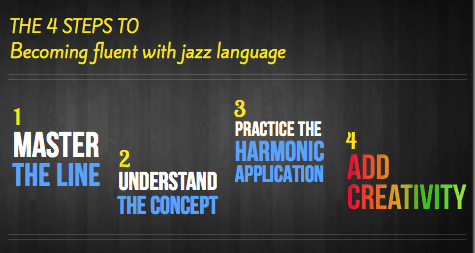

The 4 steps to jazz language fluency

Jazz is a language and acquiring useful jazz language is essential.

The whole process of learning the jazz language can seem overwhelming and ambiguous as there’s so much to focus on.

But, just by becoming fluent with one piece of jazz language you can begin seeing results today.

When you’re fluent with a piece of language, say a dominant 7 piece of language, you now have a line and a concept of how to approach a dominant 7 chord.

You have more than a lick, you have an understanding, a visceral intuitive knowledge that allows you to play musically over a sound, instead of having a purely intellectual concept of how to go about things rooted in music theory.

With fluency in jazz language, music theory supplements and supports your knowledge, ear training practice becomes more applicable, and jazz improvisation starts to make sense.

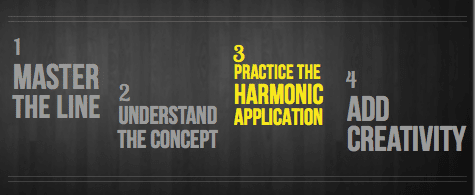

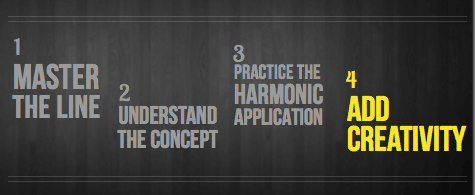

Here are the four steps of becoming fluent with a particular piece of jazz language:

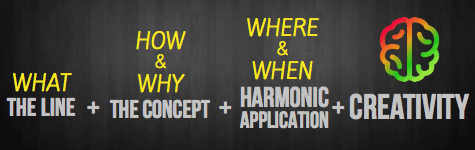

And what do each of these steps entail? What information do they hold?

The line you’re transcribing and studying is “The What.” It’s the substance.

The concept behind the line is “The Why” and “The How.” It answers the questions, Why does it work? and how does it work?

The harmonic application is “The When” and “The Where.” It tells you where in the form you can use it and the precise harmonic situations when it will sound good. And creativity is exactly what it sounds like.

Let’s take a look at each one of these steps…

Step 1: Master the line

So you’ve transcribed a line you like and you can play it on your instrument. What’s next?

The first step with jazz language is always to master the line. And by master, I mean completely know inside and out. This may take days, weeks, or even months depending upon the line and your experience with learning lines.

But you have to remember your goal. Your goal is to use this line to inspire your own creativity, which we’ll cover later, and the only way a line can do that is if you don’t have to think about it when you play it.

It’s like speaking.

The more words, phrases, and ideas you have mastered and don’t have to think about, the easier it is to communicate effectively and creatively.

Communication becomes difficult when you have to think about the definition of a word or can’t remember a particular word for a specific context, or perhaps you can’t recall how a word fits together with some other words.

In all these cases, thought gets it in the way.

And because jazz improvisation is a real-time activity, there’s no time for thought.

So, how do we ensure that thought will not impede our creative flow?

We master the line by:

- Visualizing it in all keys

- Playing it in all keys—review this process to practice lines in various root movements

- Alternating between visualizing and playing it in all keys

Things to remember when mastering a line:

- Go slowly, use a metronome on 2 and 4 and gradually increase the tempo

- Know what chord you’re playing over when you play the line in all keys—you should never be on autopilot. This is where visualization skills really come in handy. The goal is more than technique, so you need to know where this line works, which will elaborate more on later…

Step 2: Understand the concept behind the line

Once you master the line, you probably have a pretty good idea of how it’s constructed and what makes it tick, and if you don’t then chances are you don’t know the line that well, so this step is a good test to make sure you’ve mastered the line.

So once you’ve truly mastered the line, it’s time to look into the logic behind the line, and I don’t mean just the general theory.

There’s a big difference here…

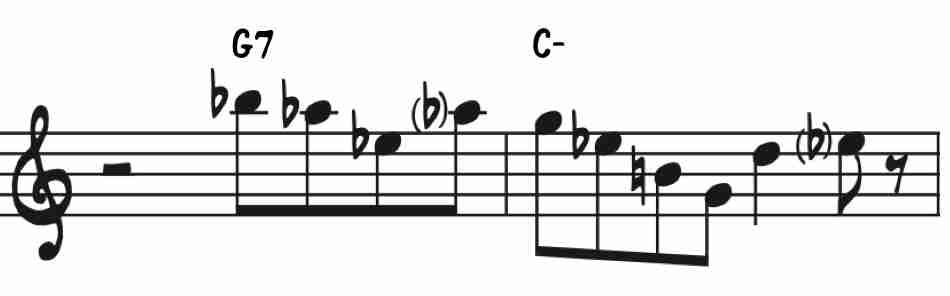

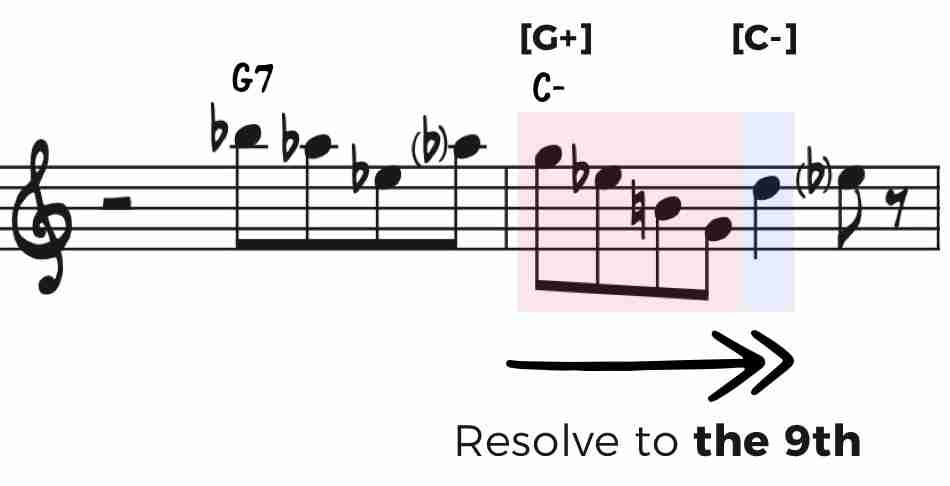

For example, take the opening line from Michael Brecker’s solos on Softly as in a Morning Sunrise:

It starts at 00:40 second in. Here’s the line slowed down quite a bit…

If I put this line under the typical jazz-theory microscope, I may miss some very valuable ways to implement this information. Let’s take a look…

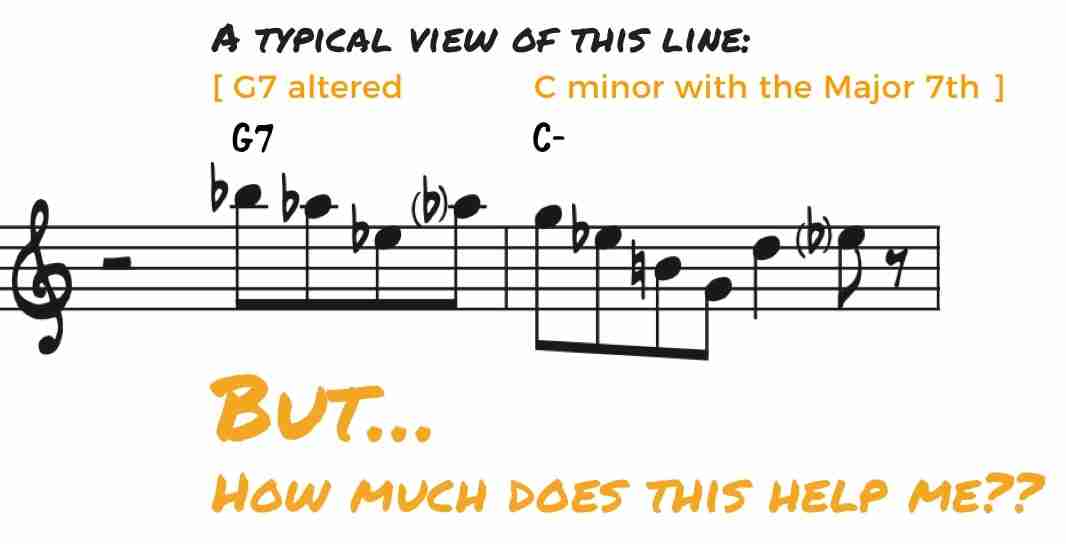

A very typical view of this line might be to call the first part G7 altered and the second part a C minor with a major 7th like this…

This isn’t wrong and you’re probably looking at the example thinking yeah, it is G7 alt and C minor with a major 7th, but how much practical knowledge do I gain from analyzing it this way?

Well, I now know that Michael Brecker uses the altered scale…or does he?

Yes, all these notes in the first bar are contained in the altered scale, but that doesn’t mean he had the altered scale in mind to create that part of the line.

Nor do I actually know if he really had the major 7th in mind in the second bar…

The truth is, you never know exactly what the improviser was thinking about in that moment to come up with what they played, however…

It’s your job to translate what you’re discovering into meaningful concepts that mean something to you so that you can apply them and get an equally effective result as the player you studied.

To understand this line, and make it useful and applicable for me, I need to think about:

- What makes it special?

- What makes it unique?

- How does it work?

- Why does it sound great?

- How can I best think about this concept to use it in my own playing?

And the way that I think about it may be totally different than the way you think about it. What’s important is that you understand the concept behind the line in a way that you can then make use of the information.

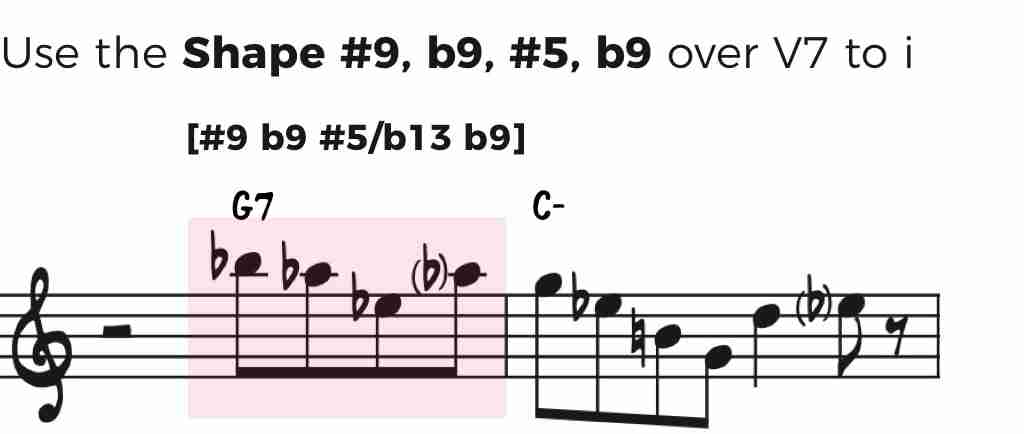

To me, it’s the shape of the line in the first bar that makes it so strong. So, I would highlight this as a specific technique that I can directly apply in the tunes I’m working on, like this…

Pretty straightforward, huh? Now I have a clear, concise, easy-to-apply concept that makes sense to me.

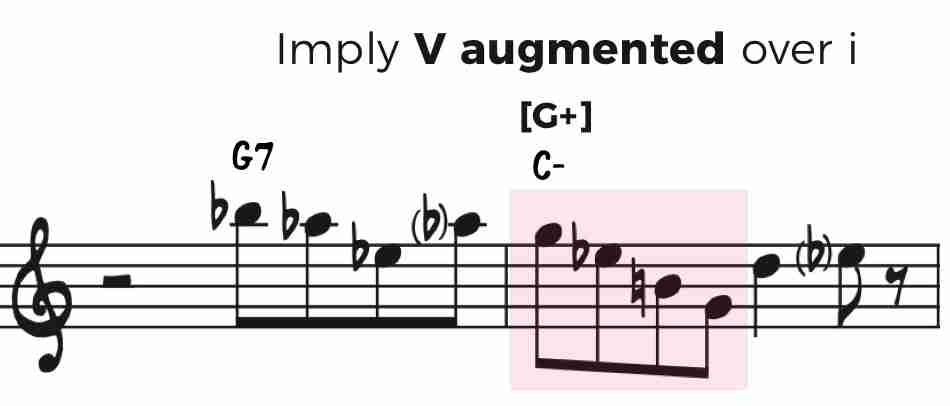

And just within this little line, there are many other techniques to pull out, like this powerful one – implying the V augmented triad over the tonic minor chord.

Again, a simple technique that makes sense to me and will be easy to apply in real-time when I solo.

And here’s an example a very subtly piece of information that you might use – rather than resolve to any note, try resolving to the 9th like Brecker does…

Another clear tactic to take advantage of that’s easy to miss…

Now I spot at at least three more important concepts that I could use. Can you find them? Hint: They don’t all have to be melodic.

Notice in all these cases the emphasis was not on analysis, it was on how can I interpret the concepts of this line so I can best use them in my own playing?

Very very different.

Now, supposing I’ve mastered the line and I understand the concept, now what?

Well, before we move on to the next step, realize that there’s a ton you can do now.

You have a line that you’ve mastered and gained a tremendous degree of technical and mental facility with because you mastered it in step 1, and you’ve also gained an understanding of the concept(s) that make(s) this line sound great in step 2.

Now you have options and options are always good. You can use the exact line in your jazz improvisation, parts of the line, or you can use the concept(s) behind the line when you solo, or you can even use a combination of both.

When you understand the concept(s) behind a line and can easily apply them, the single piece of language opens the door to improvisational freedom

Step 3: Practice the harmonic application

This is more than having the intellectual understanding about what chord the line is played over.

Practicing the harmonic application means that when you play the line in all keys, you can feel how the line is connected to the chord you’re playing it in at any given moment.

It’s a little difficult to describe.

If you do it right, when you play the piece of language you’re working on, it embodies the chord sound and feeling.

The line could stand on it’s own because you hear how the melody of the line expresses the sound of the chord.

In this way, the line is more than just a series of notes, but it’s a melodic interpretation of harmony.

The simplest way to practice this: apply the line you’re working on–or the concept behind the line as we talked about in Step 2–to parts of a tune where you know it works.

So, if you’re practicing a one measure minor line, use it in any tune you’re working on where a bar of minor happens. Repeat this over and over, and eventually that piece of language will become a tool of expression for you over minor chords.

Step 4: Add YOUR creativity

There are infinite ways to be creative in anything, not just music.

You just have to be willing to experiment a little and try things without seeking permission or advice

Creativity begins when you think to yourself, “What if I tried this instead?” and you try something that no one told you about or led you to. You simply decided in the moment that it might be worth a shot to try something off the standard path.

How do we get off the standard path and become more creative?

Often it’s just about asking the right question.

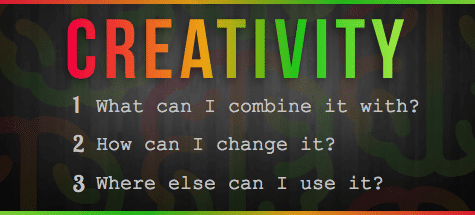

Once you’ve mastered a line, understand the concept behind it, and practice applying it to tunes for a specific harmonic situation, start experimenting.

It’s easy to make a line your own, or to make your own exercises form the line.

If at any point you’re stuck or don’t know how to add in your own creativity, simply ask yourself these three questions again and again:

- What can combine it with?

- How can I change it?

- Where else can I use it?

These three simple questions will take you far because they propel you toward infinite new ideas.

Attaining fluency with jazz language

These four steps if practiced diligently will lead you toward freedom with jazz language and each piece of language will allow you to improve exponentially!

You don’t need thousands of lines or even hundreds. Start with one, then add another…you’ll be amazed how much you can improve with each new piece of language if taken through this process.

And revisit these steps often. In my experience, the biggest mistakes are:

- Avoiding all keys – Make sure to master the language you’re working on in all twelve keys. Yes, it’s difficult. Yes, it takes time. And yes, the key of F# will never be as easy as the key of C, but work through it.

- Getting stuck in analysis – Focus on how you can actually use the information, not just understand it intellectually. Remember, the whole point is to make the language a part of your playing vocabulary.

- Not understanding the harmonic application – Knowing when and where to use the language you’re getting is very important. Without it, the line will rarely come out in your playing. Also, make sure to practice applying the line to these situations.

- Not adding your OWN creativity – Be creative. Try new things and experiment. You do not need to ask for permission, just go for it!

Focus on the 4 steps we went over today, avoid the big mistakes, and you’re well on your way to becoming fluent with jazz language.