You want to play exciting solos. Ones that will make the audience sit on the edge of their seats, that’ll make you stand out from every other musician in the room. But when you improvise everything ends up sounding exactly the same..

Many musicians share this frustration and for many it goes right back to the standard approach to improvisation that you find in most books. The mentality that each chord has a designated scale:

- Major scales for major chords

- Dorian for minor chords

- Mixolydian for V7 chords

This is a fine place to start, but if you limit your harmonic and melodic approach to these 3 scales you’ll end up feeling trapped inside of a musical box.

However, listen to some of your favorite solos and you’ll notice that the best players aren’t always following these “rules.” In fact, everyone from Charlie Parker to Brad Mehldau has used non-diatonic notes in their solos.

Notes that don’t belong in the chord, notes that don’t fit into any particular scale, yet they still sound good…

And the same can be true for you, if you know the right way to use them.

You’re too creative to settle for the same old scales in every solo! Here are 5 ways to escape the diatonic trap and start thinking outside of the box when it comes to jazz improvisation…

1) Learn to alter V7 sounds

The most common place you’ll find non-diatonic notes in the solos of great players is on the V7 chord.

And when you’re looking for ways to expand your own harmonic vocabulary the V7 chord is the easiest place to start.

The dominant chord is a natural spot to add harmonic tension before resolving to the one chord, specifically by altering the upper chord tones – the 9th, 11th, and 13th.

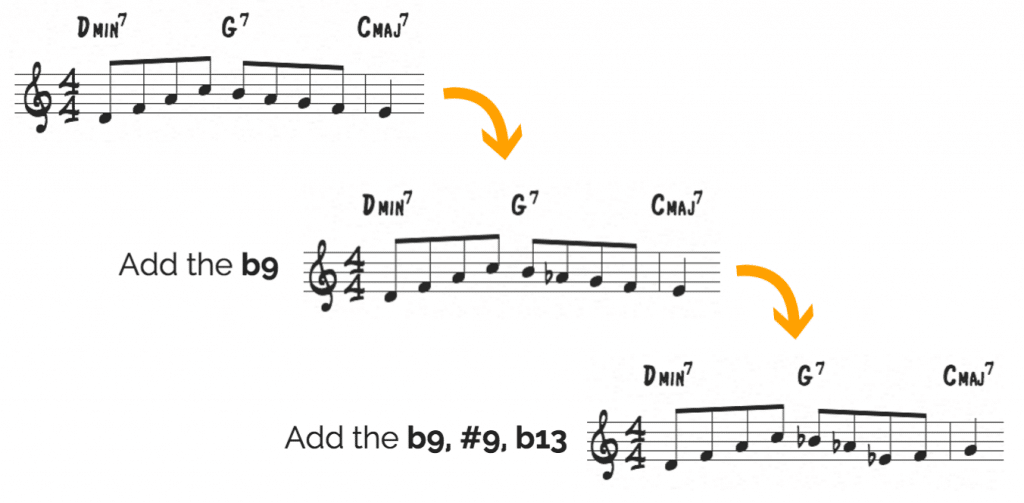

For example, you can take a simple ii-V7 line that you already know and alter the upper structures of the V7 chord:

With a few simple note changes, that simple ii-V-I line takes on a completely different character.

By learning to alter the chord tones of the V7 chord you’ll open up the door to a new world of harmonic possibility. You don’t have to reinvent the wheel on dominant chords – you can simply augment the language that you already know.

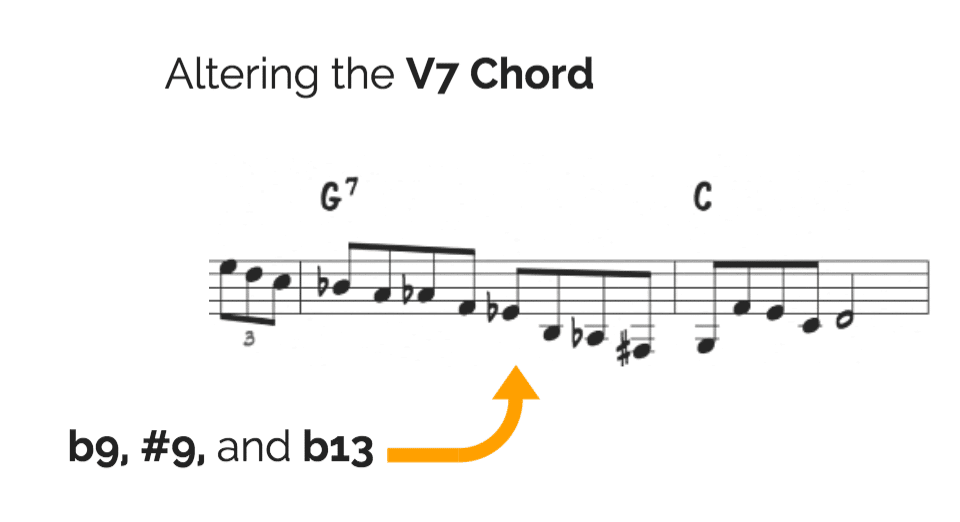

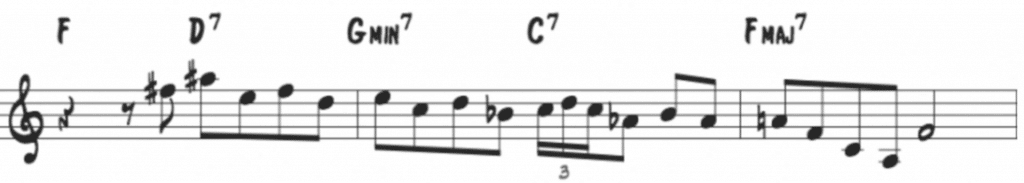

Listen to this excerpt from Charlie Parker’s solo on Cheryl and pay attention to how he approaches the G7 chord:

Now take a close look at how he alters the diatonic notes of the G7 chord. By using the #9, b9 and b13 over the G7 he can create a completely different “dominant sound.”

Each altered note, used by itself or in combination with other altered notes, adds a unique ‘flavor’ to the V7 chord. Study how the best improvisers use these sounds in their solos – listen closely to their ii-V-I’s or how they navigate the bridge to rhythm changes.

Simply inserting these notes or an altered scale based on music theory is not enough, you need to know how to use them melodically. You’ll be much more successful when you learn to hear the unique sounds of these altered dominant notes by ear.

Check out this article for more ideas on the V7 chord and then Learn to Play V7 to I Like a Pro!

2) Emphasize non-diatonic notes

One of the biggest challenges as you progress as an improviser is to break free of the beginner mindset of music theory…

Scales, chords and strict rules for constructing melodies.

We learn these rules in the classroom and ingrain them in the practice room, but when you get on stage you need to adopt a different mindset. Here it’s all about creativity, almost like an experiment with sound.

Any note is fair game if you can hear it…

Just because a note isn’t in a chord or part of a specific scale doesn’t mean that you can’t play it!

Take a listen to some of the most famous jazz solos. The greatest improvisers frequently relied on outside harmonies to add color to their solos…and so should you.

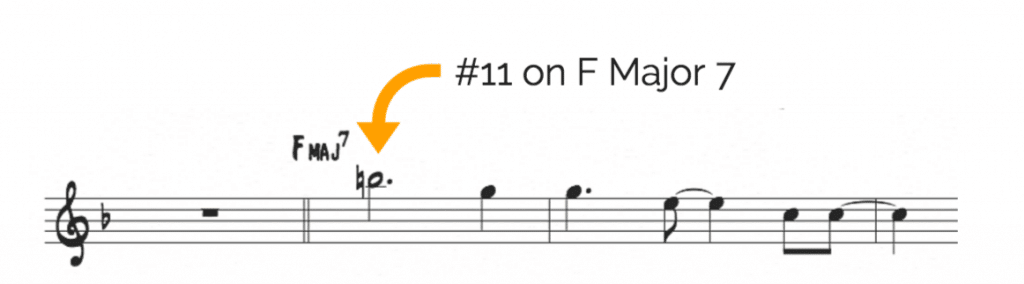

For instance, check out how Miles Davis uses the unique sound of the #11 to add color in his solo on Four:

The #11 grabs the attention of your ear because it’s dissonant and unexpected. However, once you become accustomed to the sound it will become yet another color that you can employ in your solos.

As you listen to more and more players, you’ll hear altered notes on the V7 chord over and over again. And you’ll find dozens of players using the #11 on Major and Dominant chords.

But that doesn’t mean that you have to stop there…

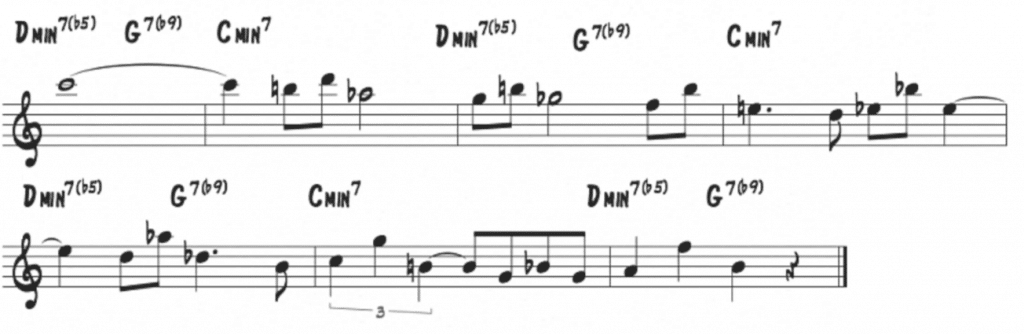

Listen to how Rich Perry uses a sequence of non-diatonic notes in his solo on Softly as in a Morning Sunrise:

In this short passage you hear him utilize a number of nontraditional note choices:

- Playing the Major 7th on a minor 7 chord

- Playing the Major 7th on a V7 chord

- Playing the b13 on a minor chord

Your harmonic adventurousness all depends on what you can hear – the sophistication of your ear. If you only know the sounds of major thirds and sevenths, that’s what you’ll play in your solos. Aim to expand the awareness of your ear to include non-diatonic notes.

For more ideas on playing outside of the harmony, check out this lesson for Premium members!

3) Utilize chromatic patterns

Another method that you can use to escape the diatonic routine in your lines is to take a chromatic approach to melodic construction…

If you’ve listened to any Miles from the mid to late 60’s, you’ve probably noticed that he plays lines that include a lot of chromaticism. And many great improvisers have also used this technique in their approach to soloing.

Check out how Woody Shaw begins his solo in the video below:

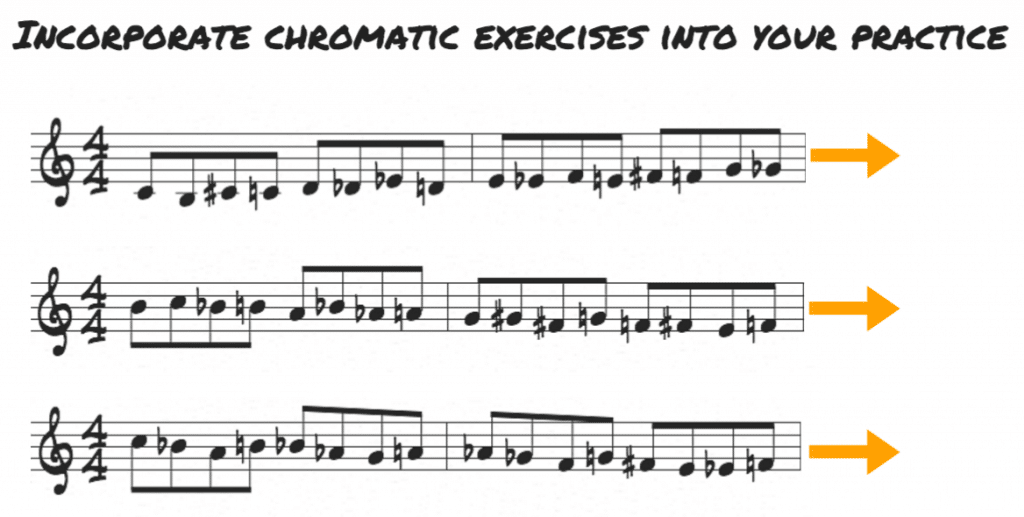

At 2:21 Woody starts with this extended chromatic pattern:

Woody plays a sequence of whole steps that move up chromatically, occasionally landing on goal notes that fit the chord. In your own solos you can use chromatic lines to move to goal notes or create forward motion in your musical line.

This is also an exercise that you can easily incorporate into your warm-up routine. For example take the line that Woody plays and see how you can vary it:

Just like diatonic scales, remember to practice these chromatic patterns in all four directions!

4) Implying major over minor

Beyond altered dominant chords and chromaticism, another way to slip out of the traditional harmonic constraints of music theory can be found on minor chords.

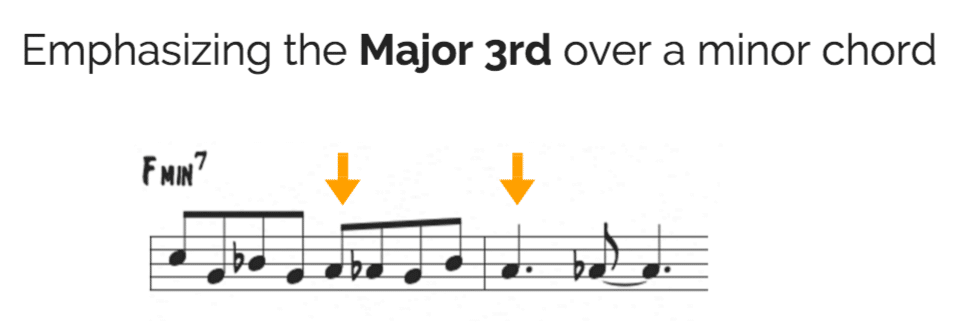

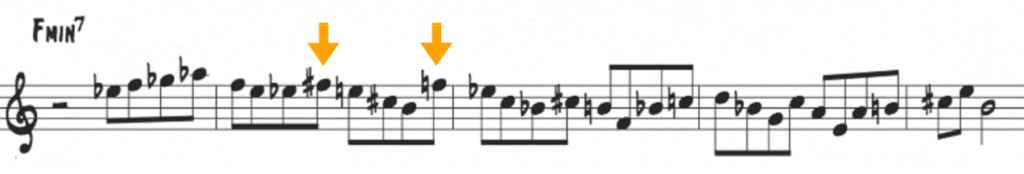

Check out how Woody Shaw alternates between the minor and major 3rd on an F-7 chord in this live solo over Stepping Stone:

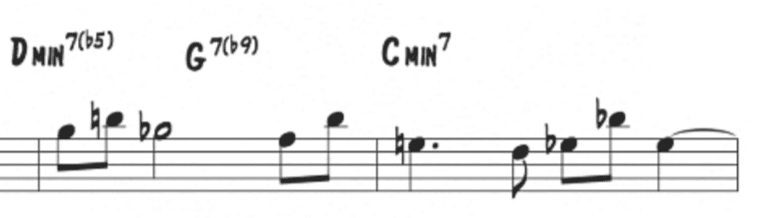

And if you take another look at that Rich Perry example from Softly as in Morning Sunrise you’ll find him using the major 3rd over minor and diminished chords as well:

Over the D-7b5 he emphasizes an F# (Gb) and over the C-7 chord he lands on an E natural. Each creates a harmonic dissonance that is briefly resolved in the following notes.

Aim to incorporate the major 3rd over minor 7 in two ways – as a passing tone and as an emphasized note that creates harmonic tension.

5) Symmetrical scales and patterns

In any style of music, the ear responds to patterns, repetition, and symmetry. And the same is true of the musical lines that you create in your own solos.

A sequence of notes that follows a logical pattern gives the ear something to latch onto…especially if the harmonic terrain is unfamiliar or dissonant.

Here are a few examples of symmetrical scales and patterns that you can employ in your solos…

1) The whole-tone scale is built entirely of whole steps. Listen to how Lee Morgan utilizes the whole tone sound in this line from his solo on Hocus Pocus:

2) The diminished chord is built on a series of minor 3rds. Take a listen to Coltrane’s famous diminished lick from the 2nd chorus of his solo on Moment’s Notice:

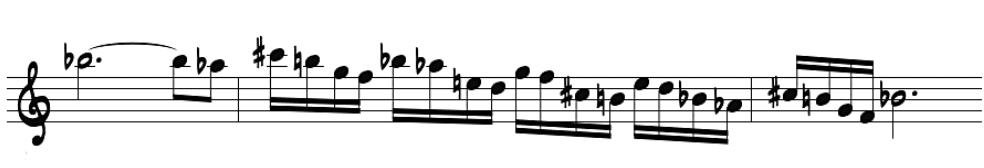

3) Sequential patterns are another way to create symmetry in a line that goes outside of the written harmony. Woody Shaw utilizes a pentatonic pattern that descends by half-step:

Woody uses this four note pentatonic pattern to alternate back and forth between F minor pentatonic and F# minor pentatonic.

Start by brushing up on your whole-tone scales and diminished arpeggios in all 12 keys. And be sure to check out this post for some more ideas on playing outside of the harmony.

Start thinking outside of the box…

Now it’s time for you to take these ideas into the practice room.

Start by incorporating these concepts into the language and lines that you already know: a ii-V, a minor line, a tune that you are memorizing, etc.

Here are a few practice ideas:

- Alter the upper structures of the V7 chord (b9, #9, b13)

- Transcribe what your favorite soloists are playing over V7 chords

- Take a non-diatonic note and apply it to a familiar chord or progression

- Try creating a melodic line out of only chromatic structures

- Practice alternating between the minor and Major 3rd on minor chords

- Work out a whole-tone or diminished pattern and apply it to V7 chords

Each of these ideas will take some serious practice to master, so pick one at a time and start slowly. Along the way listen to your favorite players for inspiration and guidance and use the examples above as a starting point.

Remember, you might have started improvising with a set scale for every chord, but it doesn’t mean that you have to stay that way forever!