Every musician has spent time in the practice room working on etudes. Diligently running through exercises that cover various techniques like articulation, the altissimo range, or diminished arpeggios. This is a good start for most players, but where does the jazz musician turn to develop the techniques that are essential for improvisation? After all jazz is a music that you learn by ear, not from a dusty book of exercises…

Well the answer can be found in an unlikely place: the repertoire of jazz standards that we’re all expected to learn.

By using jazz standards as your etudes, you’ll kill two birds with one stone: learning tunes and developing the techniques necessary for jazz improvisation.

Below we’ll show you how to turn 8 jazz standards into the daily practice etudes that will transform your skills as an improviser.

Before you get started, listen to the YouTube clip of each tune. You can either learn the melody from the recording (a great way to work on ear training!) or find the sheet music. For each tune we’ll:

- Give you an excerpt of the first 8 measures

- Show you what you’ll learn and what to focus on as you practice

- And highlight unique practice ideas specific to each melody

Ready to go? Awesome, time to meet the 8 jazz standards that are your new practice etudes…

1) Moving from Major to minor: Ornithology

One of the first bebop tunes many players learn is Charlie Parker’s Ornithology, a 32 bar melody over the chord progression to How High the Moon:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LUo-6JfVoTIOne common chord relationship that pops up in the jazz repertoire is parallel motion – the direct movement from a major chord to its parallel minor. Practicing the melody to Ornithology in all 12 keys is a great way to ingrain this concept into your technique.

Start by isolating the sequence in major to minor in the first four bars:

The goal is to be able to think quickly when it comes to switching a phrase between major and parallel minor. After you’re comfortable with that, move onto the second phrase:

If you master this exercise, it will prepare well you for the other jazz standards that share this parallel minor relationship: Just Friends, On Green Dolphin St., How High the Moon, and I’ll Remember April to name a few.

2) An exercise in 3rds: Jitterbug Waltz

You’ve probably practiced your major scales in thirds before…

But the trick comes in translating this standard exercise into a musical technique that you can use in your solos.

Working on Fats Waller’s Jitterbug Waltz forces you to apply this sequence of 3rds in a musical way, all within the context of time. Take a listen:

There are a few key concepts that make this melody more musical than a scale pattern: Notice (1) how the melody starts on an upbeat, off setting the predictable pattern, and (2) how the line extends past the octave, getting away from the root to root mentality of major scales.

You’re already playing scales in the practice room, so why not incorporate this 8 bar sequence into your warm-up routine? Practice it with a metronome and take it around the cycle, keeping the phrasing and articulation of the line in mind.

3) Developing diatonic language: Joy Spring

Clifford Brown is one of the most melodic improvisers ever to play this music. And his tune Joy Spring is a great example of creating interesting melodic lines with simple diatonic material:

When many players hear the word ‘diatonic’ they think of scales and arpeggios…and this is exactly what you end up hearing in their solos.

But you don’t have to be stuck running scales to play diatonically. As you play the melody to Joy Spring notice how the shape and intervallic content of the line adds to the character of the tune. And check out how the simple addition of ornamentation creates interest in the melody line.

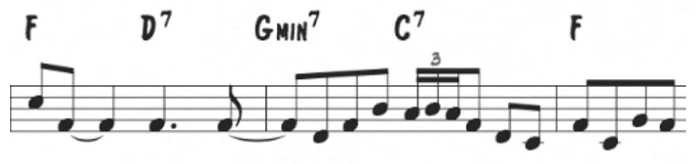

Remember, a good melody (or solo line) doesn’t have to hit each chord tone of the progression every single time. For example, take a look at the turnaround at the end of the excerpt:

Over the I-VI-ii-V progression he uses only diatonic material in F. You don’t have to be a prisoner to every chord in your solos, strive to create melodies over music theory.

4) A Scale Workout in all 12 keys: Parisian Thoroughfare

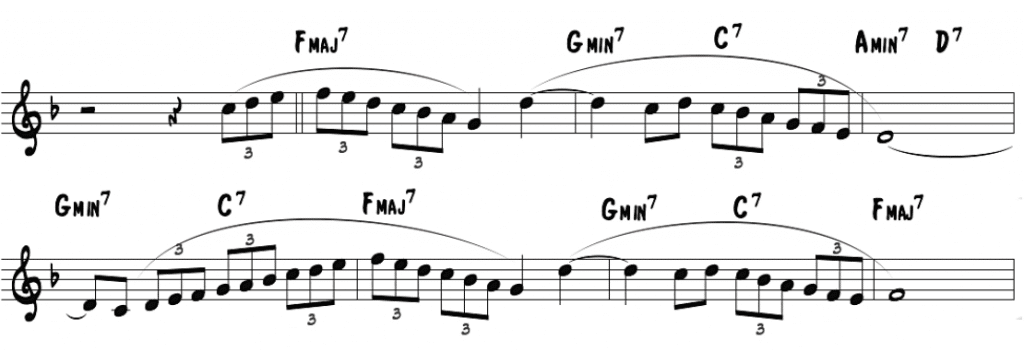

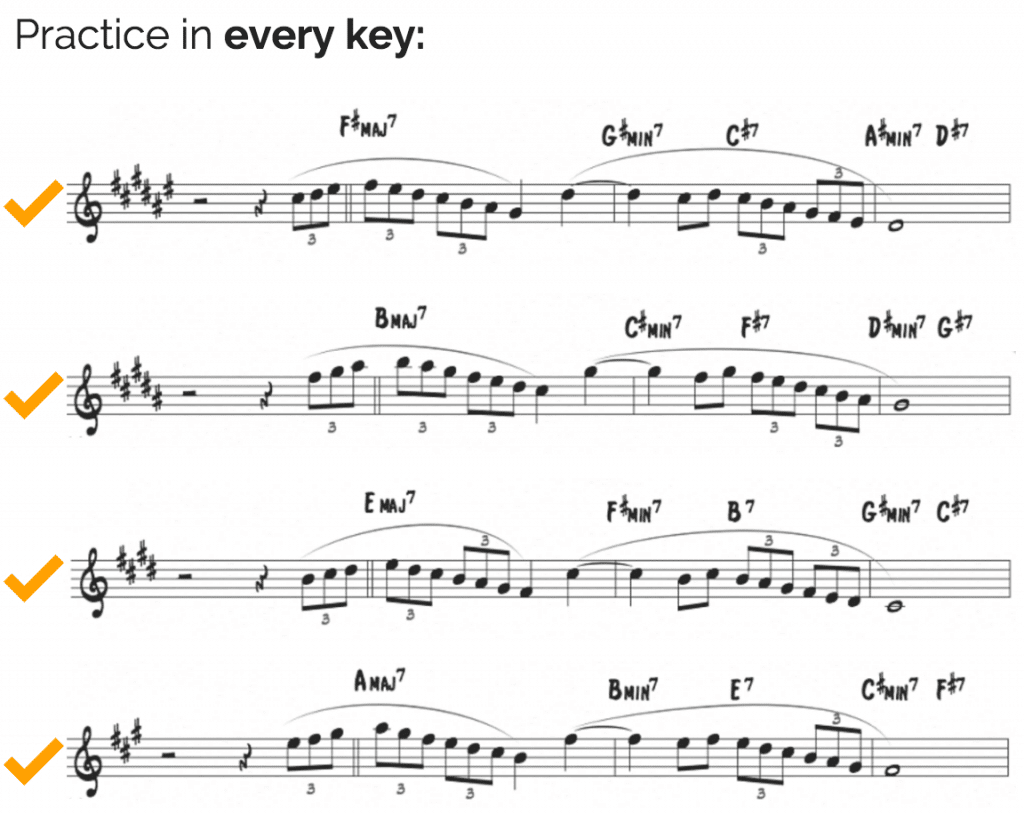

The melody to Bud Powell’s Parisian Thoroughfare is composed of mainly one thing – a major scale. However, the secret to sounding good is how he uses this scale in the context of a tune:

Start with the metronome = 80-100 bpm and increase until you can play it with ease at 200. As you increase the speed, try to feel it in cut time.

Remember, this is not just an exercise in running major scales. It’s a melodic application of major scales. Think in musical phrases!

Practicing this melody in all 12 keys is a great way to gain facility on your instrument. Focus on the more difficult keys first.

Having technique in every key is essential for jazz improvisation, but being able to apply this technique in a musical way is what sets the best players apart.

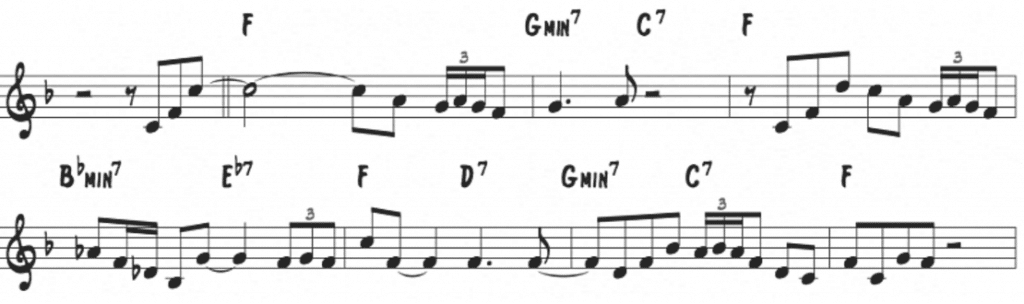

5) A Linear approach to Rhythm Changes: Room 608

One tune that every improviser must master is Rhythm Changes.

How do you create a long line that sounds good over the first 8 bars of tune?

A great way to learn how to create lines over this progression is to practice Horace Silver’s Room 608:

Start by taking a few bars of the line and learning it in every key:

Now you have a I-VI-ii-V line in that you can play in all keys. After that work on the first 8 bars as one line. Study what devices Horace uses to create a long melodic line and how you can use these in your own solos.

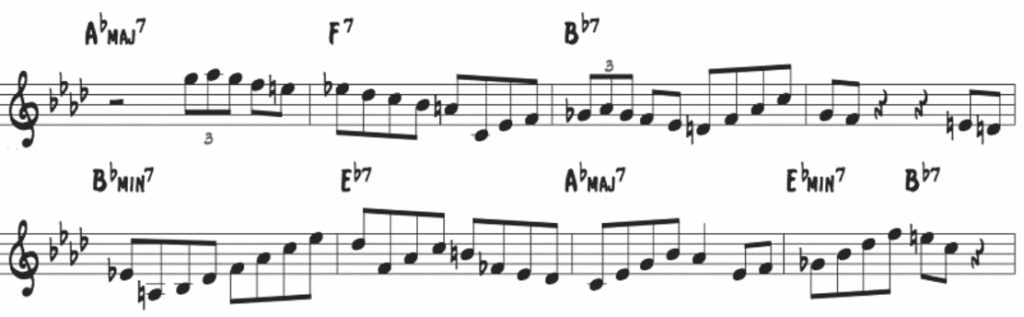

6) A Bebop Etude: Donna Lee

Some melodies in the jazz repertoire are so challenging that learning to play them is like diving into an etude. Donna Lee is one of these tunes:

This tune is a standard bebop line in terms of shape, rhythm, and harmony. As you practice, figure out where to articulate the notes without losing the flow and swing/time of the line.

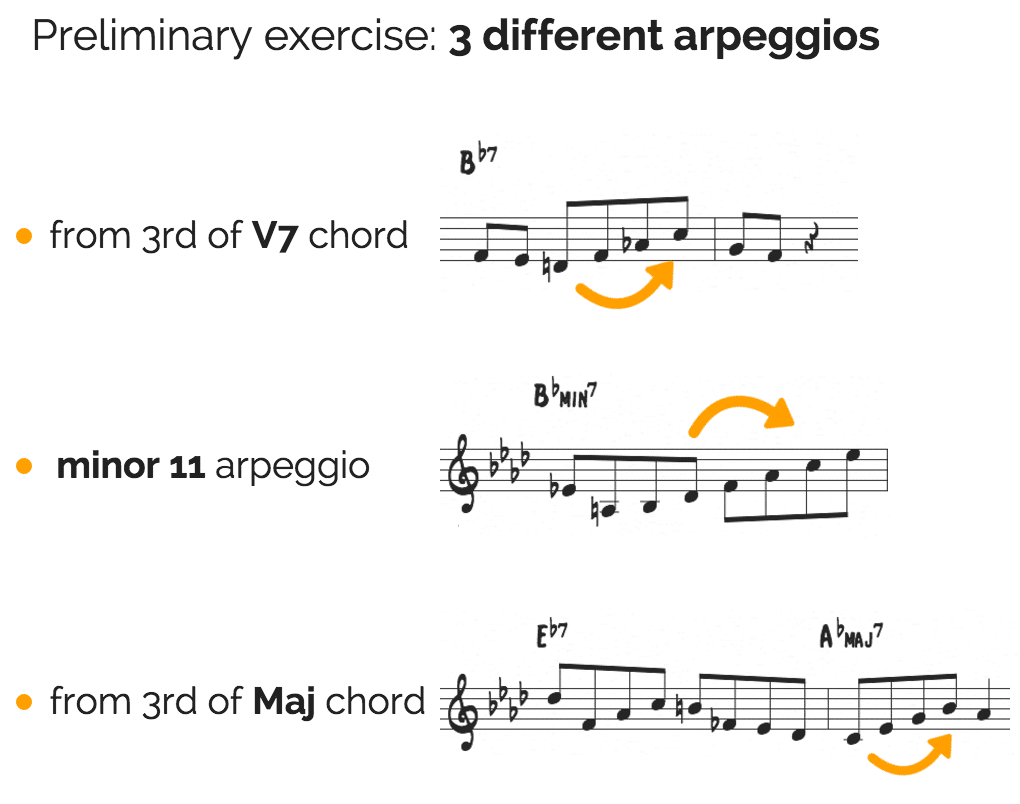

Just like any etude you need to isolate patterns and sections to master one at a time. For example in the first 8 bars of the tune there are three different types of arpeggios happening:

Work out each of these arpeggios in all keys before you begin so they are under your fingers. Also take note of the other musical techniques common to bebop like enclosure, chromaticism, and V7 alterations.

Remember to focus on the articulation and phrasing of the opening line. Every great player has a personal approach – here’s how Clifford Brown plays it on the album The Beginning and the End:

Check out how Clark Terry or Chris Potter or Eldar plays the melody. Which style of articulation and phrasing matches the concept you have for your own sound?

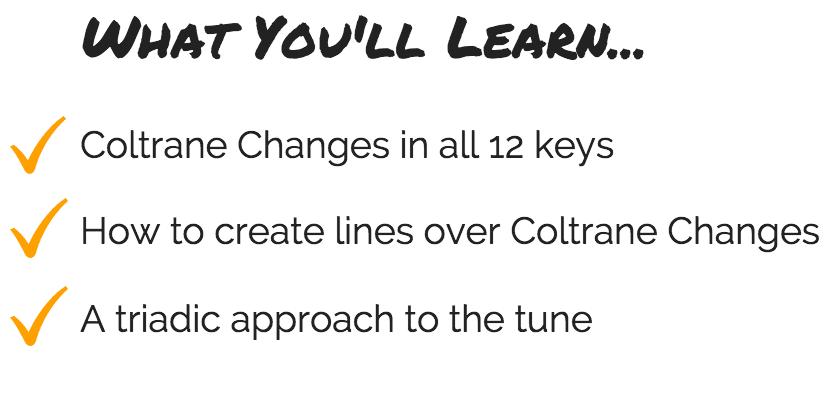

7) Focusing on Coltrane Changes: 26-2

A challenge for many improvisers is navigating the chord changes to Giant Steps.

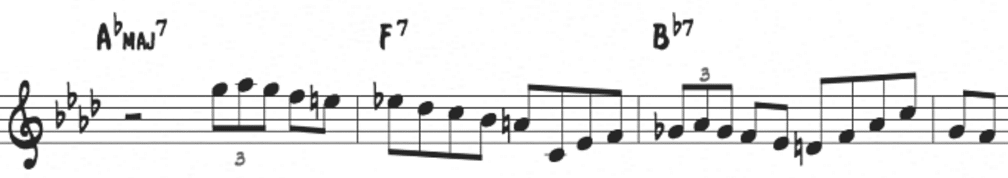

But rather than jumping in and trying to create a solo out of thin air, why not study a melody line that Coltrane wrote himself? Take a listen to his tune 26-2:

A good preliminary exercise is to start by visualizing Coltrane changes in every key. That way when you get into the practice room you don’t have to spend time thinking about the chords.

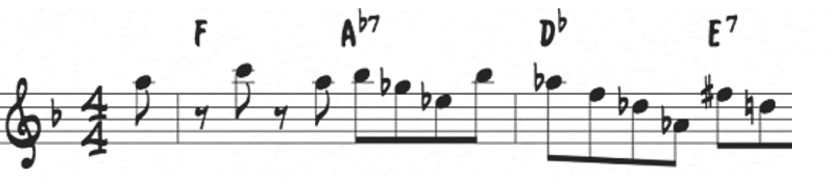

Break down the line into smaller pieces and work on those one at a time:

Repeat it slowly, thinking about the underlying chord relationships as you do. Then take the sequence around the cycle, covering every key.

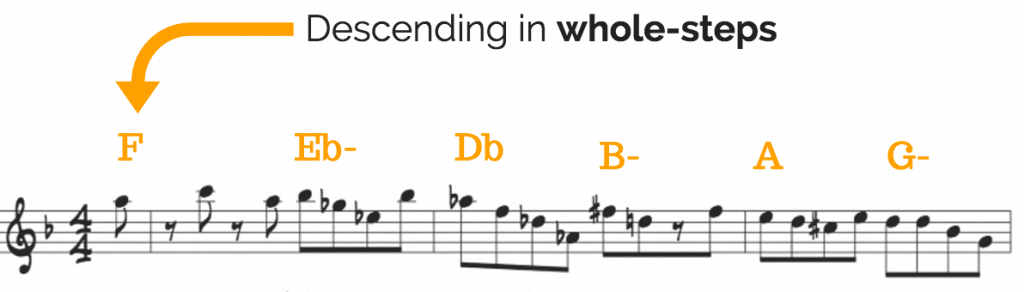

As you do this, notice how the melody is moving down in a whole-step pattern – using the 3rd and 5th on major chords and the related minor ii triad on the V7 chords:

Practice this descending “major to minor triad” sequence in every key. With this exercise, you’ll not only ingrain the melody to 26-2, you’ll have a new way to approach the changes to Giant Steps.

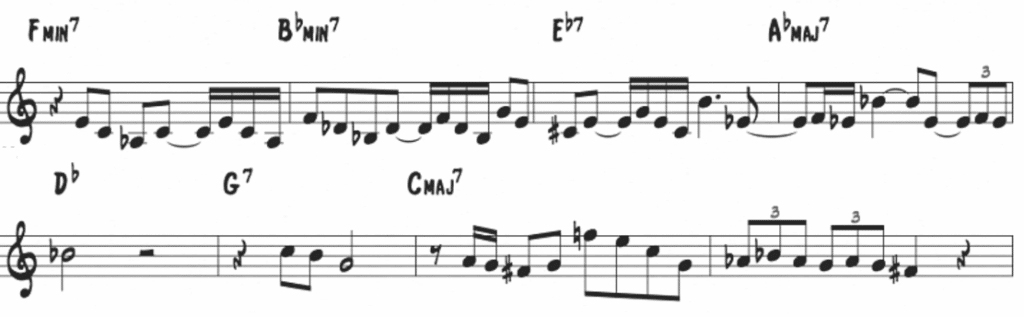

8) Thinking outside the box: Ablution

The last tune we’ll look at is Ablution, Lennie Tristano’s contrafact over the chord progression to All the Things You Are:

Tristano’s melody is a great exercise in thinking outside of the box when it comes to rhythm, phrasing and harmony. Notice how he creates a completely different approach to the familiar changes to All the Things You Are.

Practice the melody line slowly with a metronome, gradually increasing the tempo until you can play along with the recording.

Time to get started…

Start by selecting one of these 8 standards to focus on in the practice room. Treat it like any other etude that you would normally practice.

For example, let’s say you have 30 minutes to practice. Take the melody to Parisian Thoroughfare.

Spend a minute listening to the recording, then once it’s in your ear, play the melody along with the metronome. Focus on your time, your sound, your articulation, etc. In your mind think about what chord(s) you’d play this line over…

Suddenly you are working on the same techniques as any other etude you’d practice, plus a whole lot more.

If you spend the next few weeks working on these “jazz etudes” you’ll expand your vocabulary, improve your time and articulation, learn to play longer lines, and develop the techniques you need as an improviser.

And the best part? You now have 8 new tunes to add to your repertoire!