John Coltrane is probably best known for Countdown and Giant Steps, or his earth-shattering intensity on A Love Supreme. But often overlooked is the depth and beauty of his phrasing and lyricism…

When I first heard the album Kind of Blue, I was blown away.

And I still am to this day.

There is so much there. Every time I listen to it, I hear more.

One solo that has always hit me dead-center between the eyes is Coltrane’s solo on Blue in Green.

This solo transports me to another world…

But this is not the Trane that we think of. The one that’s pounding down the door, in your face, playing faster than what seems humanely possible!

No. It’s a different side of him, yet the intensity of his playing is still just as present.

And much of this intensity has to do with how he phrases.

What’s the secret behind Coltrane’s beautiful phrasing and how does he sound so lyrical?

Does Coltrane phrase like a pro?

Over five years ago, I wrote an article about how to phrase like a pro.

In that I shared four points about phrasing that pros do and amateurs do not:

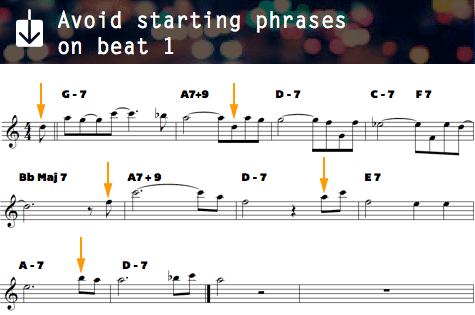

- Avoid starting phrases on beat 1

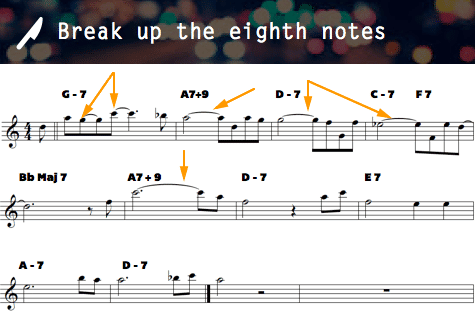

- Break up the eighth notes

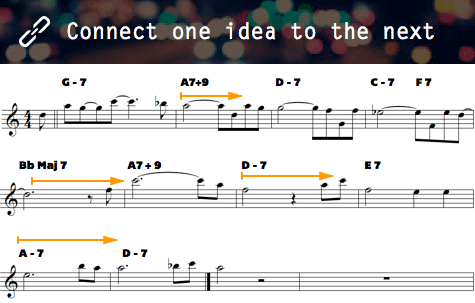

- Connect one idea to the next

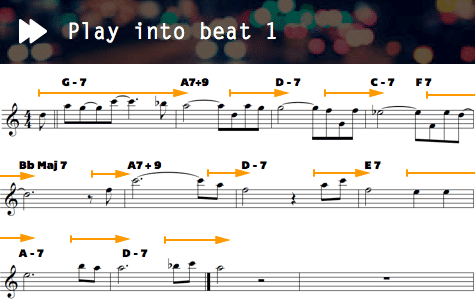

- Play into beat 1 and beyond

They seem simple, right?

But, as many things go, the simpler they seem, the more difficult they are to put into practice.

Do pros really do these things? Am I just making things up or guessing?

Well, let’s take a look at Trane’s solo on Blue in Green and see what we find.

Listen to the whole track. His solo starts at 2:26:

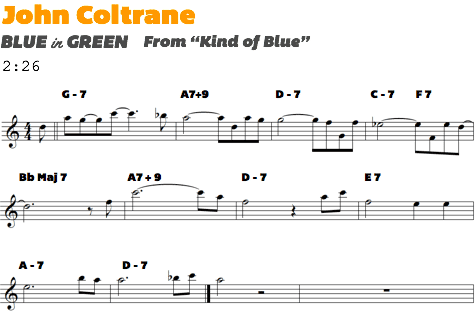

Now let’s take a look at the first chorus of Coltrane’s solo. It’s a 10 bar form and we’ll use that chorus as our study material throughout:

So, does Trane follow these 4 guidelines to phrase like a pro?

He does not start phrases on beat 1 in this excerpt, not even once!

He’s constantly starting phrases an eighth note, or two or three, before the next measure, pushing every phrase he plays forward.

If you don’t phrase like this right now and you tend to start every line you play on beat 1, begin to practice this concept by starting every phrase you play from the And of 4.

You can either add an approach note to an existing line to practice this, or you could shift the line a half a beat early, the point is to get used to starting lines on other beats than beat 1.

Once you’ve practiced from the and of four, shift back to start phrases on beat 4, then the And of 3, then 3, and so on..

A simple tactic Trane uses to break up the eighth notes is to use longer note durations over up-beats, which end up looking like ties when you write them out.

Try holding over notes like this in your own practice to break up constant strings of eighth notes, a habit we’re all guilty of.

Every single idea Coltrane plays leads beautifully into the next. He doesn’t play one idea and then a completely unrelated idea. His ideas flow naturally from one to the next, it’s almost as if one phrase completes the next, constantly having natural continuations…

The concept of playing into beat 1 is probably the most important to phrase like a pro. Every phrase pushes and lead to beat 1 of the next measure. No, beat 4 is not the goal. Beat 1 of the following measure is.

You can hear –and see– that Trane always does this here.

Reframe how you think of a measure so that you’re always pushing toward beat 1.

So, does it look like Coltrane phrase like a pro?

Is that even a real question? Of course he does.

Now let’s look at some other aspects of Trane’s phrasing and lyricism that we can perhaps make use of in our own playing.

Phrasing: a balancing act

Phrasing is a balancing act between opposite forces.

Length, direction, intervallic content, rhythm, tempo, volume…they all play key roles in the overall effect achieved.

Coltrane is a master at balancing his phrases between these opposites.

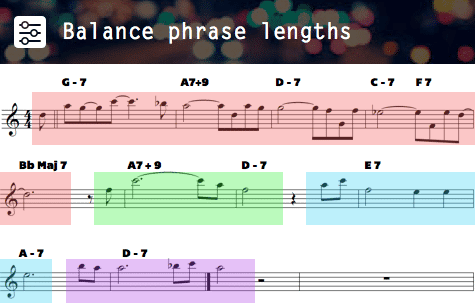

Notice how Coltrane begins with a long phrase, but then immediately follows it up with a series of shorter phrases. Phrase length is not something we often pay attention to, yet it’s hugely important.

Practice soloing with just one phrase length for a chorus, say short 1 or 2 measure phrases. Then another chorus try soloing with 4 or 5 measure phrases, and on another chorus try 8 measure phrases.

Practicing exercises like this will help you become aware of controlling the phrase length and will then help you better balance your solos as a whole between short, medium, and long phrases.

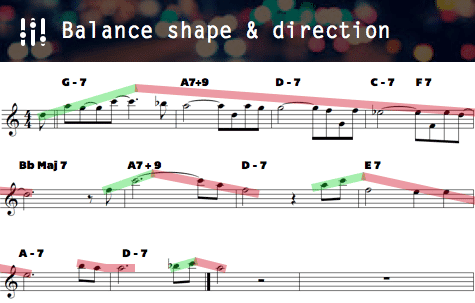

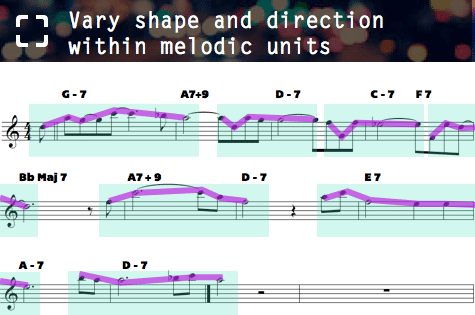

The overall shape and direction of each line Coltrane plays is carefully balanced between upward and downward shapes and direction.

Do you play lines that most of the time go up? or down? or do you even know?

Start to become aware of it and balance your phrases between upward and downward motion to create interest.

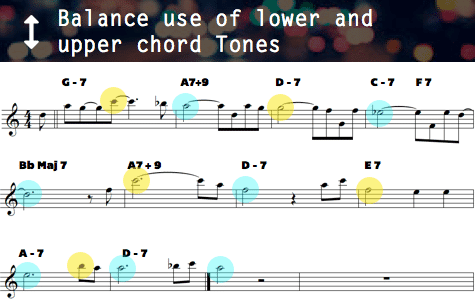

This chord tone balancing concept is something that Coltrane does that’s exceedingly cool. Listen to the solo again and try to hear where the points of tension and release are.

What did you hear?

The points of tension are where the upper chord tones (9 11 13 – shown in yellow) occur and the points of release happen on lower chord tones (1 3 5 7 – shown in blue)–as an interesting side note, realize that the “B natural” in measure 9 played over A-7, stays in our ear and is heard more as the 13th over D-7 in the next measure.

A lot of times when we’re first getting into jazz improvisation and learn about upper structure chord tones, we think they’re better or more important than lower structure chord tones.

This is not the case.

All chord tones have a purpose, even the ones that teachers tell you to avoid. They’re all just sounds and they’re used in different contexts to achieve different effects.

Balancing your phrases between the use of lower and upper chord tones will give them a sense of drama as you continue to move from points of tension to release.

Lyricism: it’s what’s on the inside that counts

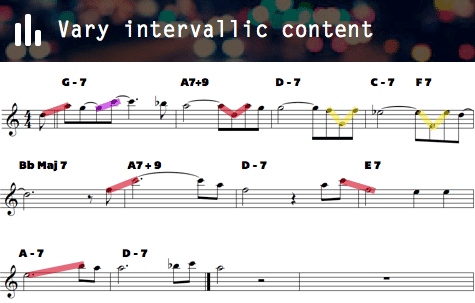

As we’ll see in this Coltrane excerpt, a large part of his beautiful lyricism comes from what’s contained in each small melodic fragment within each phrase, or even the relationships between the various notes within a phrase, the intervals.

Let’s take a dive into what Trane is doing at this small detailed level…

Just as Coltrane varied the shape and direction of each phrase, within each melodic unit–the small packages of melodies within each phrase–he varies the shape and direction of the notes.

What does this variation do?

It creates melodic interest.

Many people run up and down scales all day. Or, the run up and down arpeggios all day.

Either way, what are you not doing when you’re doing either one of those things? You’re not varying the shapes and directions of notes in an interesting way, hence it sounds boring.

Study what Coltrane is doing here with shape and direction and get away from just running scales or arpeggios in favor of creating melodic interest.

Closely related to varying the shape and direction, look at some of these intervals Coltrane is using!

- Red represents a perfect 5th

- Purple is a perfect 4th

- Yellow is a minor 7th

Most people stick to small intervals. Trane mixes in the use of much wider intervals, which…what do you think achieves?

Yes, you got it: creates melodic interest.

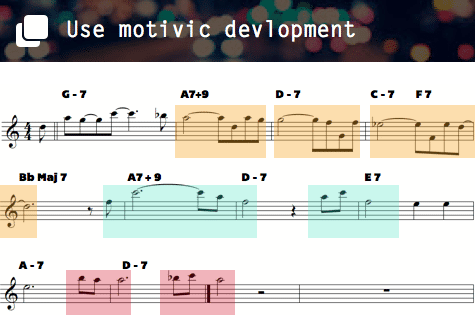

And lastly, Coltrane implements the use of a tried and true tactic for creating lyrical melodies: motivic development. Within just 10 bars he develops three different motifs.

The first time: he develops the motif by keeping the same rhythm, similar intervallic content, and lowering the pitches.

The second time: he develops the phrase by changing the order of the notes. First it’s FCAC, then he leaves the first note out and plays ACF, all part of a major triad by the way, increasing the strength of the melodic structure as well.

And the third time: he develops the phrase by leading toward an A in two different ways. Simple, but effective.

Motivic development is difficult to master, but easy to begin using.

Start with just two or three notes and see if you can develop them either rhythmically by changing the rhythm, or melodically by changing the pitches.

Now it’s your turn to learn from the lyrical John Coltrane

Although he might not be best known for being a lyrical player, John Coltrane was up there with the best.

As you can see by going through just 10 bars of his solo, there’s so much to study and learn from in every detail he plays…

- How he starts phrases

- How he breaks up standard rhythms

- How he connects phrases

- How he plays through to beat 1

- How he balances phrase lengths

- How he balances phrase shape and direction

- How he balances his use of lower and upper chord tones

- How he uses shape and direction on a small scale

- How he varies the intervals he uses

- How he uses motivic development

Today we went pretty deep into phrasing and lyricism, and yet we still barely scratched the surface! There’s always more to learn, another angle to take, another takeaway to be had…

When you transcribe for yourself and interpret the things you’re finding in your own way, you’ll gain even more.

And one of the questions we get a lot is how do we transcribe, analyze, and interpret so easily?

Besides doing it for a long time, it all goes back to the ear. I can honestly say that all the skills we wrapped up into The Ear Training Method are what allow me to easily and quickly learn from my heroes.

The other day I was transcribing the chords of a tune I wanted to learn. It took me less than 15 minutes to learn the specific voicings going on. How? Because I’ve already drilled the sounds into my head that I know I’m going to encounter over and over again. Repetition is the key.

You must work on your ear.

It may not be the fun or sexy thing to work on–it’s certainly not hexatonics or superimposition–but it will give you the aural freedom you desire and you’ll become a much better musician and enjoy your craft on a whole new level.

And during your next practice session go through the techniques we went over today and see if you can apply any of them to something you’re working on or use them some way.

Select something you particularly liked and practice it slowly until it becomes something you can use in performance–which, by the way, if you didn’t notice we just released a new audio course all about reaching your optimal performance state.

Sounding lyrical and phrasing like a pro is quite challenging. Focus on one technique at a time, isolate it in your playing, and work at ridiculously slowly. In time, you’ll notice that you’re singing out of your instrument more than you ever have.