The jazz standard Blue Bossa is often referred to as a beginner jazz tune, but as you quickly find out as you start your journey into jazz, even these so-called “beginner” tunes are not easy to sound great on.

Playing beautiful lines through the changes that connect and flow from one chord to the next and craft an overall story is a challenge no matter what the chord changes are.

And playing ideas filled with unique and interesting approaches goes even beyond that, primarily reserved for those who’ve spent years exploring the jazz language.

Today we’ll study a player who exhibits this next-level skill – the one and only Dexter Gordon.

When you think big, lush, classic tenor saxophone sounds, Dexter Gordon has to be near the top of your list. But it’s not just his brilliant sound or laid-back in-the-pocket swing feel that make him great…

It’s the unique improvisational tactics within his jazz lines.

In this lesson, we’ll look at 12 Dexter Gordon lines on his solo over Blue Bossa, but these aren’t just any lines – they’re lines that have something noteworthy about them, something different…something you’d never think of…

Blue Bossa: The Chord Changes

Take a listen to Dexter playing over Blue Bossa and notice how effortless everything seems…

Now before we getting into Dexter Gordon’s solo and all the great jazz lines he plays, let’s first talk about the chord changes…

In terms of learning the changes, a great place to start with is The Form.

Go ahead and listen to the first 8 bars of the form and try to hear if it’s operating in a major or minor key…

Can you tell?

Now listen to the next 8 bars of the tune and try to do the same – does it sound like it’s in a major key or a minor key, or both?

Are you able to hear it?

If you’ve spent some time training your ear, then you should be able to easily hear when the tune is in a major tonality, and when it’s in minor, but let’s talk about this for a second…

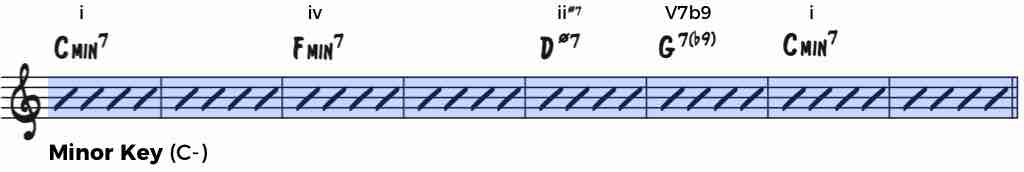

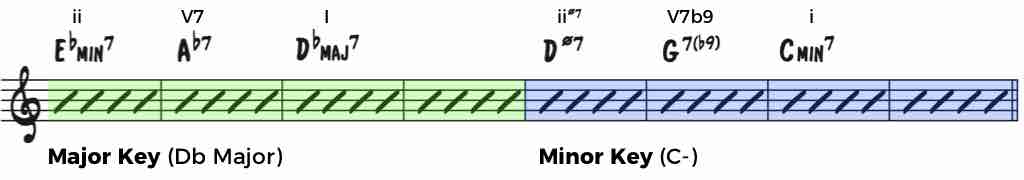

If you listen closely to the first 8 bars, the A Section of the tune, you should be able to hear that it’s in a minor key…pay attention to the minor tonality and how the changes move from the i to the iv of the key, followed by the ii and V7.

And in the second 8 bars, the B Section, hear how it starts with a ii V7 I in a major key, Db Major, but then quickly shifts back to the ii V7 of the minor key?

Being able to take a jazz standard like this and hear whether the big sections of the tune are operating in a major or minor tonality is crucial to understanding the story behind the tune, something we teach you how to do in our new course, Jazz Theory Unlocked.

And If you can hear these 2 sections, then you can hear the whole tune because the whole form only uses these 2 pieces.

That’s right, all you do is play the A Section, followed by the B Section, and that’s the entire tune, ABAB…

But remember…just because the changes might seem simple doesn’t mean that playing beautiful melodic lines is ever easy.

12 Dexter Gordon Lines on Blue Bossa

Okay, now that you have the form of the tune under your belt, let’s get into Dexter’s solo on this tune…

Now, when you transcribe licks and lines from your favorite players, it’s a good idea to understand what types of lines you’re going to find when you transcribe.

In Blue Bossa, because of the chord changes to the tune, the main things you’ll find are lines that fit over:

- C minor (functioning as a tonic)

- F- (the minor chord functioning as the iv in C minor)

- Part of a minor ii V i (in C minor)

- Part of a Major ii V I (in Db major)

These are the main types. And then, keep in mind that chords might be inserted and implied by the soloist to connect these main pieces, so always be on the lookout for these as you transcribe as well.

Alright, you know the form, and you know the types of lines we’ll find…

Next In this lesson we’re going to explore 12 different Dexter Gordon lines that illustrate all sorts of interesting and unique approaches to these seemingly simple chord changes.

In the process, you’ll discover all the things you would never think of playing on Blue Bossa…

The Natural 13th & Interesting Shapes

In this first section, we’ll look at 3 different Dexter Gordon lines that emphasize some very important concepts. The first concept we’ll look has to do with the details behind using the 13th on a minor chord…

What makes it sound good? Are there tricks to using it within your lines?

Then, we’ll get into some of the interesting melodic shapes that Dexter uses and how you can start using them, too.

LINE #1 – THE 13TH ON MINOR (@1:20)

This line is only a single measure long, so most people would probably look right past it, but often one bar or even a couple beats holds vital information that you can add to your improvisational concept.

Have a listen to this line and notice the specific way that Dexter uses the natural 13th sound within this idea.

Why you’d never think of it: Most people shy away from the natural 13th sound on minor because it’s notoriously difficult to control and has a very bright sound that stands out.

Or, if they do play it, they simply hold it out, not fully understanding how to weave it into their melodic lines in a smooth way…

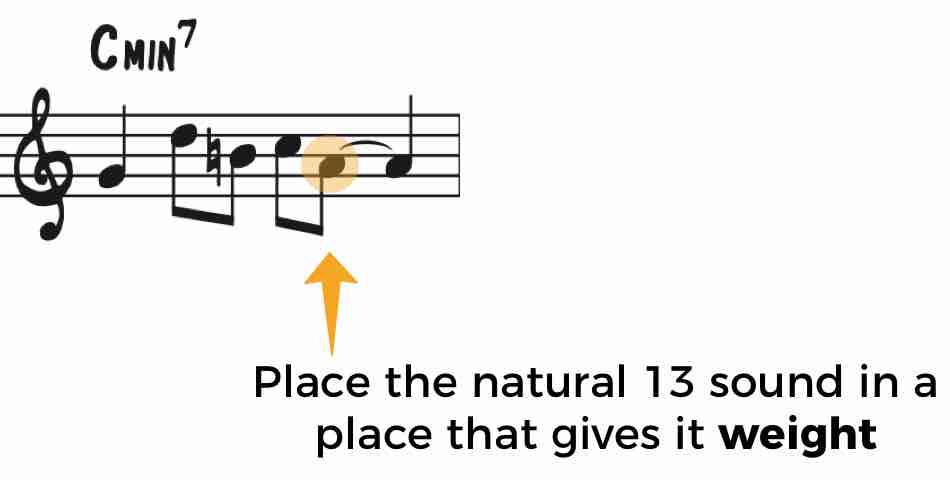

To start using the natural 13th on minor, instead of just playing the 13th on minor wherever you want, the way most people do when they randomly mix notes from the Dorian Mode, think about where you place this unique sound within your line.

In this line, Dexter chooses to place the sound at the end of the idea.

Think about whether you’re leading into it or starting from it – What beat of the measure will you land on it? How long will you hold it out?

And, think about how you can use shape and direction to guide the line toward this sound, highlighting it, just like Dexter does.

These are the types of things you want to think about in the practice room because obviously, when you’re performing, all of this has to be at your fingertips…

LINE #2 – TRIAD SHAPES (@1:41)

Shape is something that’s not given much attention when it comes to melodic lines. Rather, most people focus on mixing up notes from a scale or they try to target a particular chord-tone.

But the shapes within a line and the overall shape of the line play a huge role in the way it sounds. Now, when we talk about shape, we’re talking about the intervals within the line – the shapes that the intervals form.

In this line, Dexter uses diatonic triads over the C minor chord, but mixes them in a creative way to create interesting intervals within his line…

Why you’d never think of it: When you think about playing over minor, you probably think about playing the C Dorian Mode.

But, unless you’ve worked on this scale from many alternate angles and transcribed some language, chances are you approach it in more of a scalar fashion.

With this scalar approach, you would never play a line with these kinds of shapes in it because it’s not something you would just stumble across.

Remember, you have to go beyond the basic scale…

To start using interesting triad shapes, first understand how Dexter is using triads within this line and where they come from…

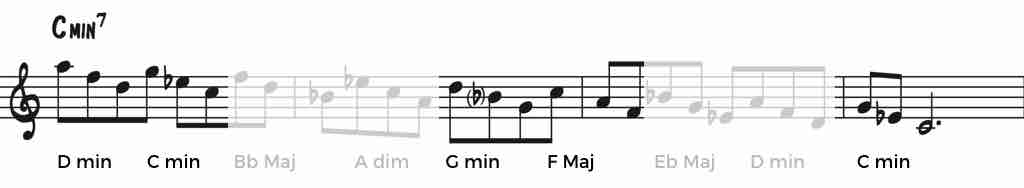

If you take a look at all the diatonic triads from C minor (with a natural 13th), you can see that his line is simply a combination of these, while selectively leaving a few out.

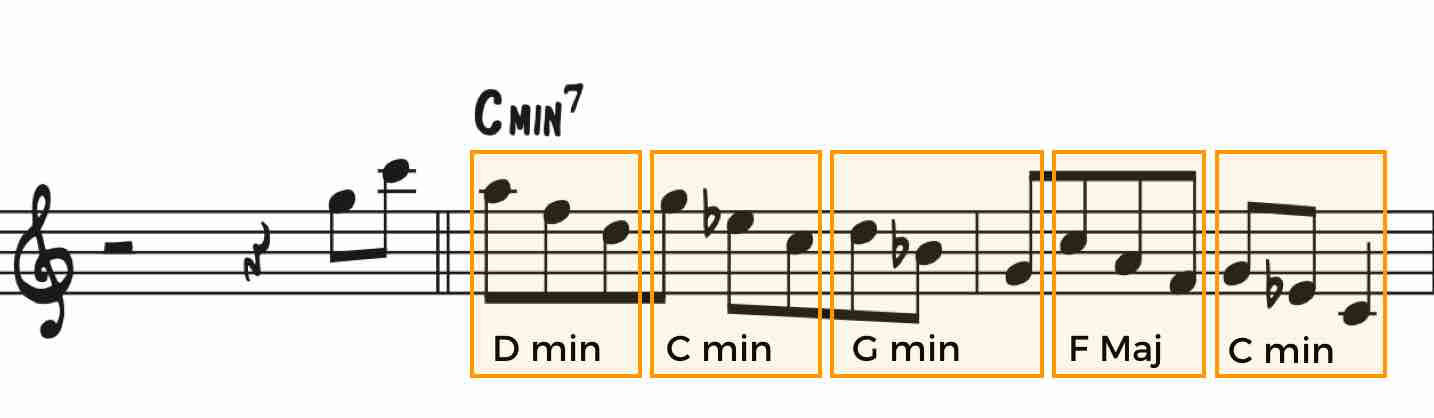

You see, his line uses the D minor, C minor, G minor, and F major triads…

Starting with D minor, you can think of this combo as this pattern: Play 2 diatonic triads, then move a whole step up from the note you’re on to the 5th of the next triad (the note C up to the note D) and play another 2 diatonic triads from there.

This pattern is what creates the interesting shapes within his line – by leaving out some of the triads that are possible, he disguises his use of triads and creates more interesting intervallic content.

You can steal this pattern or even come up with your own!

Another strategy to start using more interesting shapes in your lines is to take a specific shape from within the line that you like and work on it.

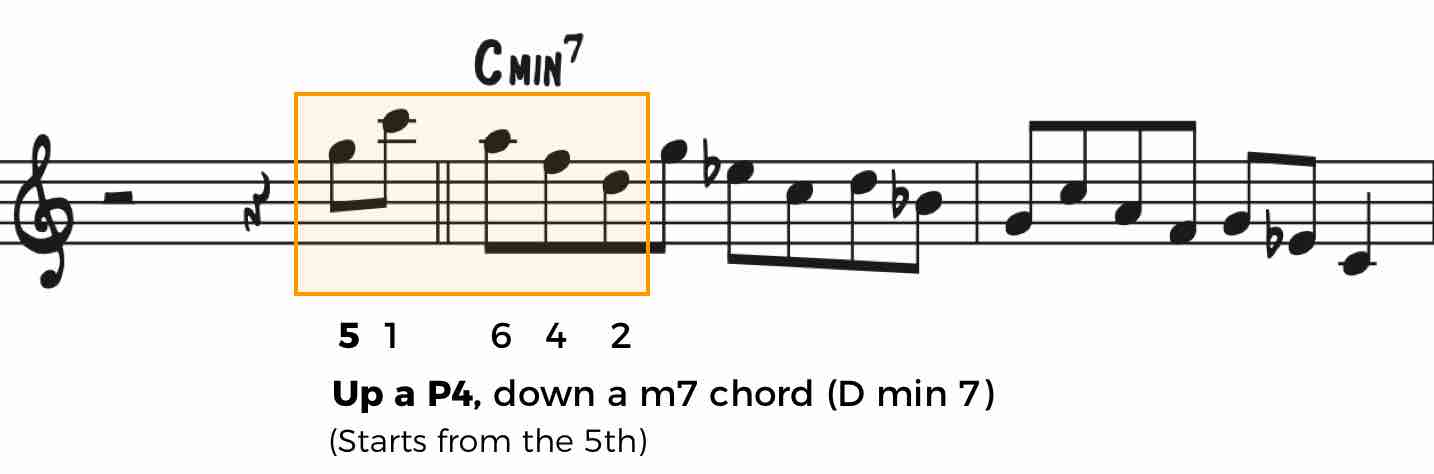

For example, I especially like the 5-note shape at the beginning of his line…

And there are quite a few ways to think about this shape…

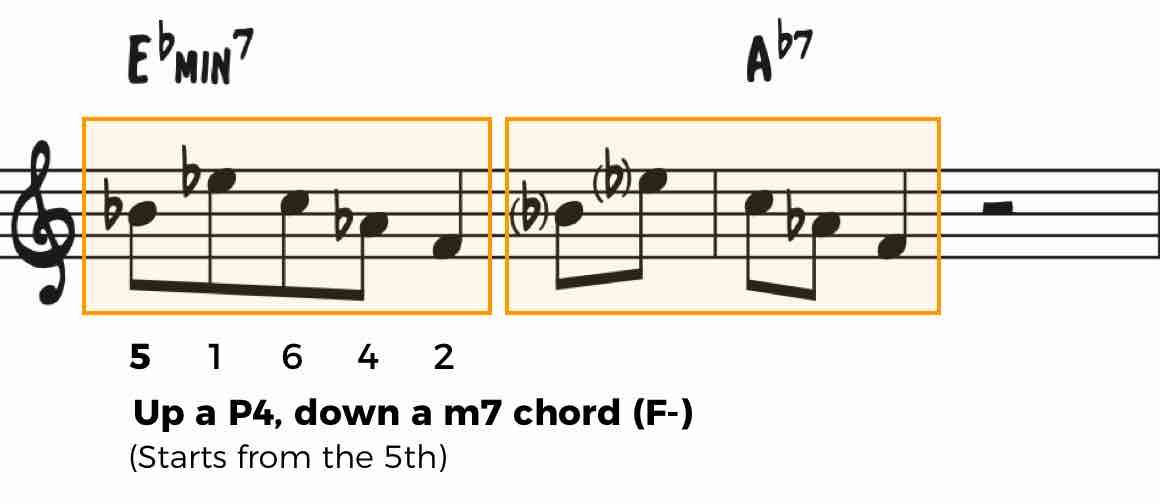

You could think of it as the chord tones 51642 on minor. Or, you could think of it as starting on the 5th of the chord, then moving up a perfect 4th and descending a minor 7 chord.

And I’m sure there are even more ways to think about this interesting shape, but the important thing is that you conceptualize it in a way that you can easily access it and add it to your improvisational concept.

Take a shape like this, play it in all keys, and start using creatively it when you improvise!

LINE #3 – SHAPES OVER ii V7S (@1:53)

Next we’ll look at another shape that will look very familiar…

You see, every good player repeats themselves. This is just the nature of having a musical personality. And within this solo on Blue Bossa, you can find Dexter using some of the same ideas throughout.

However, when great players like Dexter repeat something, they usually change up the specifics around how they’re using the information…

For example, take a listen to this line and try to hear what’s similar and what’s different from the shape in the previous line…

Can you hear it? Is he using the same shape as before? If so, is he applying it in the same way?

Why you’d never think of it: You probably think of using one melodic idea in one scenario, for example, a minor idea works over a minor chord, major fits over major and so on…

But that’s not necessarily the case. An idea can be used on other chord qualities, or it can even be used on the same quality, like Dexter does here, but starting from a different chord-tone.

And, you also might not think of this idea because when approaching a ii V7, you probably wouldn’t think to repeat the same shape you just played on the minor chord, over the dominant chord. It’s just not a natural inclination.

To start using interesting shapes on ii V7s, realize that a melodic idea can be used in many scenarios, that you’re not limited to playing it over a single chord. And then experiment with starting the idea from different chord tones and see if you can make it work.

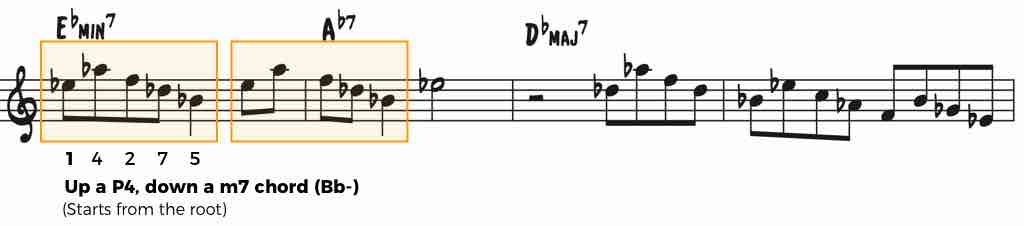

For instance, if Dexter used the same shape from Line #2 in the same way, starting from the 5th, it would look like this…

But instead, in this line, he starts the shape from the root of the chord…

So, he ends up highlighting a whole different group of chord-tones than he did in the other line.

He then repeats this same shape over the V7 chord, featuring the 13th, 11th, and 9th of the chord, which is a great ii V7 technique to have at your disposal.

Be on the lookout for shapes like this that you’re attracted to. Then, try repeating them from the root or the 5th, and experiment with how they lay over the ii and V7 chords.

In time, you’ll add new shapes to your vocabulary that can be easily applied to the full ii V7 progression.

Small and Large Intervals: Chromaticism & Octaves

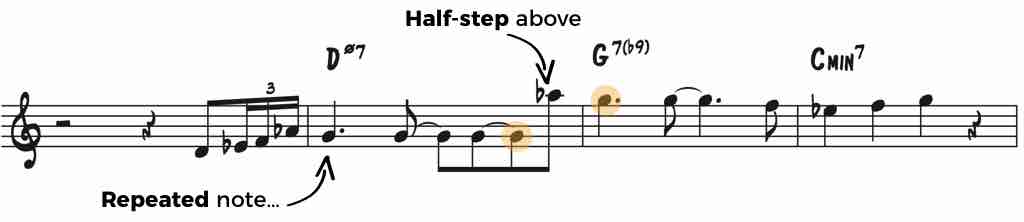

In this next section we’ll look at 2 different Dexter Gordon lines that make use of the smallest possible interval, the half-step, and the largest interval (within a single octave) the full octave.

Using both of these extreme intervals, Dexter adds a special flavor to his lines that most players don’t take advantage of.

LINE #4 – CHROMATICISM (@2:13)

One of the hallmarks of a more advanced improviser is their ability to freely add chromaticism into their lines, while still communicating the intended chord sound.

In this line, Dexter adds some chromaticism into the mix over the C minor chord, but still manages not to confuse where he’s at in the changes.

Why you’d never think of it: Chromaticism is not usually at the forefront of most people’s minds, especially if they’ve restricted themselves to a particular scale for a particular chord.

And, to make chromaticism sound good, you have to ensure that the non-chord tones are not landing in places they shouldn’t, or if they do, whether intentionally or not, you need to be able to hear and maneuver your way through this, a technique that many advanced players love to use.

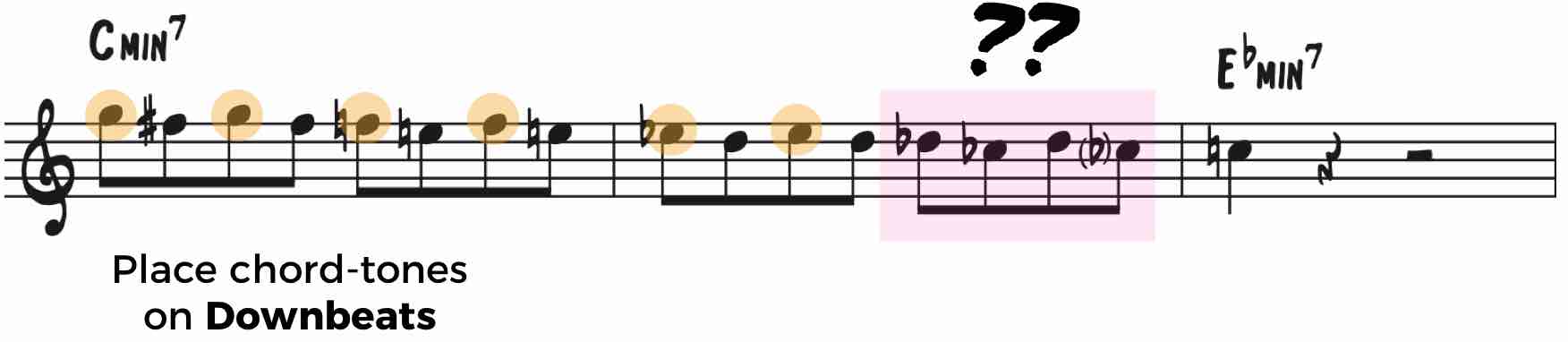

To start using chromaticism effectively, make sure that the chord-tones you place on the big downbeats (1-2-3-4) line up with the chord sound you’re aiming for.

For example, here Dexter places the 5th, 4th, and 3rd on the downbeats before playing what looks to be a b9 and a major 7th over the C minor.

But, like all great players, he’s thinking forward toward the next chord…

The Db and Cb are not a b9 and major 7 of the C minor chord, but a #9 and b9 of an implied Bb7 chord, the V7 chord leading to Eb minor.

This implied chord is yet another part of the line that you probably wouldn’t have thought about doing. In combination with the chromaticism, it creates a beautiful melodic line.

LINE #5 – OCTAVE LEAPS (@2:21)

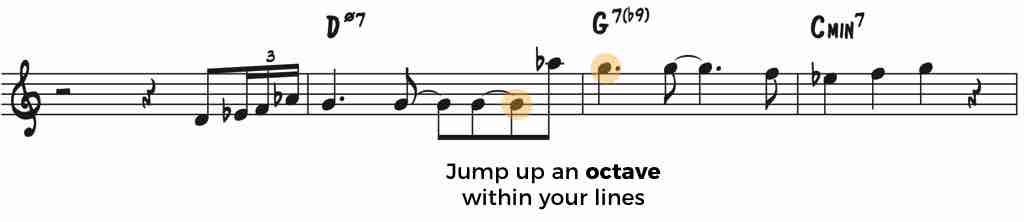

Another device that Dexter likes to use, and that you don’t see many others use, is big octave leaps in the middle of his lines.

Take a listen to this and hear the big jump in the middle of his line…

Why you’d never think of it: Octave leaps are just not a technique that most people tend to think about, I mean, why would you?

The thing is, octave jumps in your line can be quite effective if used in a musical way.

To start inserting octave leaps into your lines, observe how Dexter works them into his lines in a musical way…

He begins by repeating the note that he’ll use for the octave leap, and then he approaches the note up an octave by a half-step above it.

This is just one way that’s effective when you’re using octaves, but as you begin to put them into your playing, you’ll naturally expand from there.

It’s a simple technique that not many think about using, but one that’s easy to quickly add to your jazz vocabulary.

ii V7 Perspective & Arpeggio Note Groupings

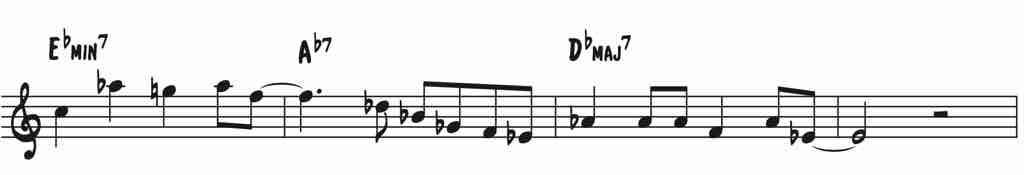

Now we’ll look at 2 more Dexter lines that showcase some very unique approaches to playing over the major ii V7 I in the B Section of Blue Bossa.

In the first line, he uses a powerful technique of changing his perspective on the ii V7, thinking of the chords in a different sequence.

And in the second line he plays an arpeggio over the entire ii V7, but groups the notes in a different way than you might expect.

LINE #6 – ii V7 PERSPECTIVE (@2:16)

This is a very important concept to understand and one of the big things that separates amateurs from professionals.

You see, the way you view the chord changes completely changes what you would play over them, and this is especially true over the ever-present ii V7 I progression.

And pro jazz musicians constantly change up how they think about this progression as they take a solo – this in turn changes up the melodic material that comes out as they improvise.

It’s simple: changes in what you’re thinking, lead to changes in what you play.

And here, rather than thinking of ii V7 I, Dexter thinks of something else…can you understand how Dexter’s thinking?

Why you’d never think of it: The first unique aspect of this line is that he plays the major third of the chord (G) on the downbeat of Eb minor. For most jazz students, this a big no-no.

Chord-tones go on downbeats, and putting a major third on the downbeat of a minor chord is against the rules, right?

Here’s the thing – It all has to do with how you hear…

If you can hear like Dexter, then you can use that major 3rd on the downbeat and clearly make it sound like a passing-tone to another note…

Anyone can hear it. The way he uses the G over Eb minor doesn’t sound awkward or confusing. It instead sounds like a pick up note to the Ab.

Now, the second aspect of this line has to do with how he’s thinking about the chord changes – his ii V7 perspective.

Rather than thinking of the standard chord changes of the tune, Eb- Ab7, he instead changes this up to Ab7 Eb-.

This might seem a bit bizarre to you, but it’s perfectly legitimate, and something you can easily apply to your solos.

To start changing up your ii V7 perspective, experiment with some different sequences of ii and V7.

Here are a few ideas to try:

- V7 for a bar, ii for a bar like Dexter does

- ii V for a bar (2 beats each), V7 for a bar

- V7 for a bar, ii V7 for a bar (2 beats each)

- ii V for a bar (2 beats each), ii V7 for a bar (2 beats each)

What other variations can you come up with?

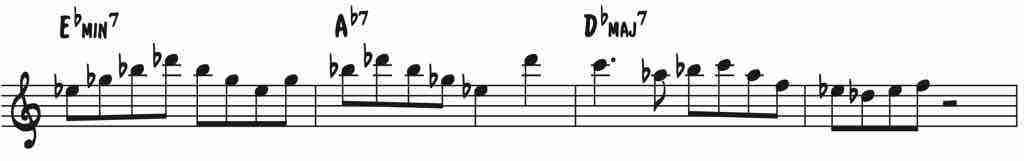

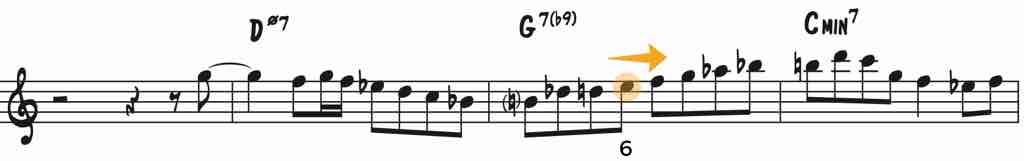

LINE #7 – ARPEGGIO NOTE GROUPINGS (@2:38)

Arpeggios are a great melodic tool…

They outline the harmony, they put chord-tones on downbeats, and they’re easy to access, but they can also sound predictable.

To counter this, Dexter does something that’s anything but predictable. Take a listen to this line and try to hear how he’s using arpeggios in an interesting way.

Why you’d never think of it: It’s common to play a simple chord arpeggio, 1357, in a note grouping of 4 notes because that’s how many notes it contains.

But rather than playing the arpeggio as a 4 note-grouping, he plays a note-grouping of 6 notes, playing the chord-tone pattern 135753.

This completely changes the rhythm of the line, as it takes up 3 beats instead of 2. Then, he repeats this idea over the dominant chord of the ii V7.

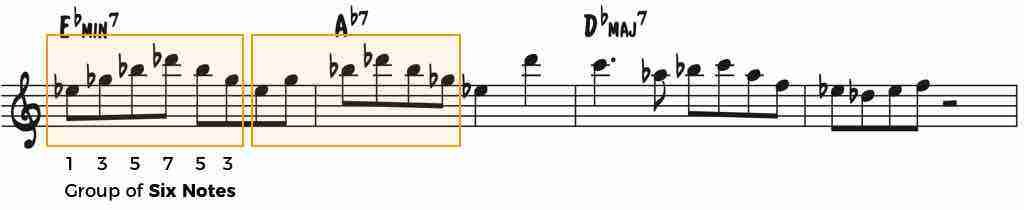

To start using arpeggios in non-4-note groups, think about using a 6-note arpeggio pattern like Dexter does. Try the original 135753, and then give some of these others a go…

What other combinations can you think of that sound good to you? What other note-groupings might you experiment with? Perhaps groups 5 or 7?

Any of these options will help get you out of the box when it comes to using arpeggios in your solos.

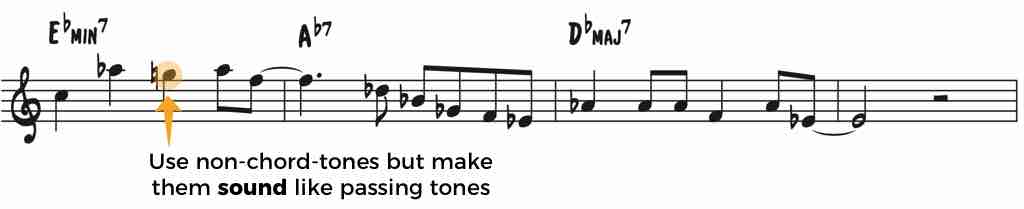

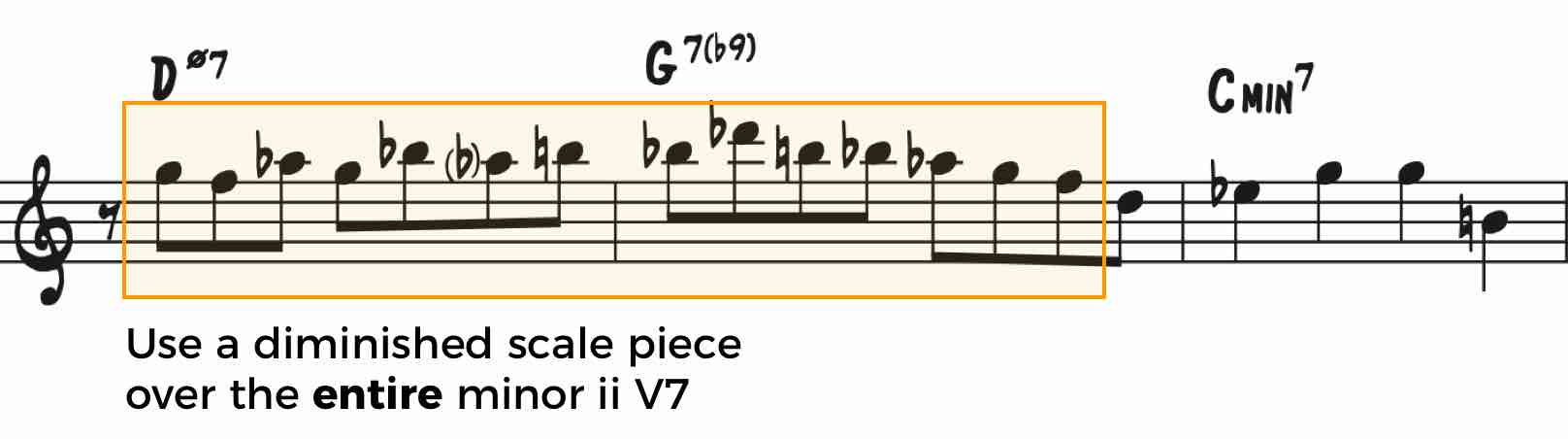

The Diminished Scale

The Diminished Scale may be easy to use, but for most people, it’s difficult to make it sound musical – It usually ends up sounding dry and mechanical.

So next we’ll look at 2 lines where Dexter makes use of the Diminished Scale in a musical way.

The first will illustrate how he uses the scale over a full minor ii V7, and the second will show you how he puts it over just the V7 chord of the minor ii V7 progression.

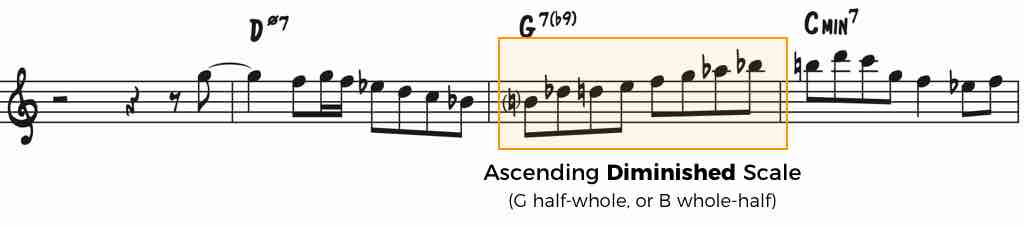

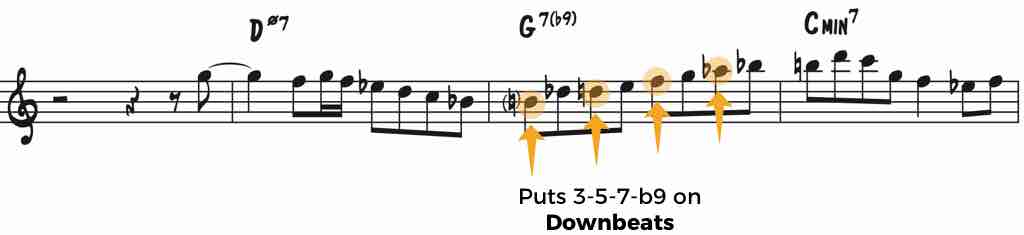

LINE #8 – DIMINISHED SCALE ON MINOR ii V7 (@2:44)

Over a full minor ii V7, both the half diminished chord and the dominant chord, you can use the Diminished Scale, but here’s the catch – you have to know what your’e doing.

In this line, Dexter Gordon moves up through a Diminished Scale in a diatonic scale pattern over the half diminished chord of a minor ii V, and then descends down the scale over the dominant chord.

So what makes this work?

Why you’d never think of it: Dexter isn’t just randomly mixing up the notes of the Diminished Scale and hoping for the best, or playing a thought out pattern like many might do with this scale.

He’s instead placing each note where he wants it to be within his line as it relates to the chord over the full minor ii V7…

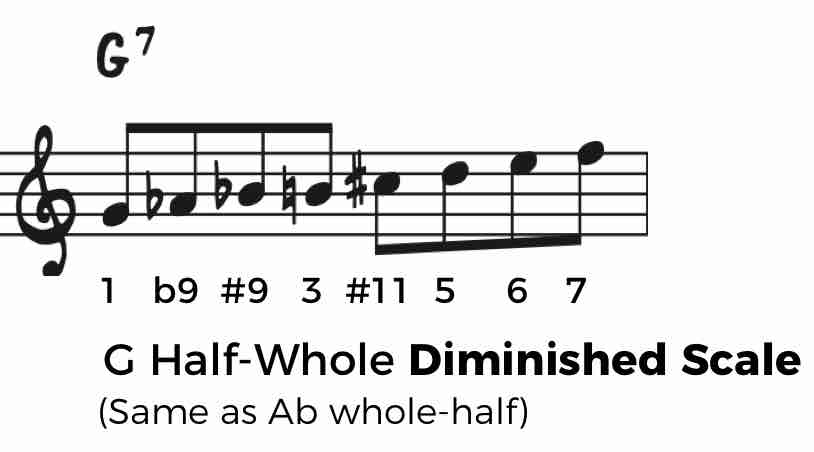

To start using the Diminished Scale over minor ii V7s, first look at what the Diminished Scale actually is in terms of a dominant chord.

To do this, view the scale starting with a half step – you can also view the scale as starting with a whole step. But to see how it relates to G7 here, make G the root, and start with a half step.

You can then easily see that the scale is simply the notes of a dominant chord, but a b9 and #9 instead of a natural 9, and a #11 instead of a natural 11. Make sure to take a look at a visual perspective of this in this lesson.

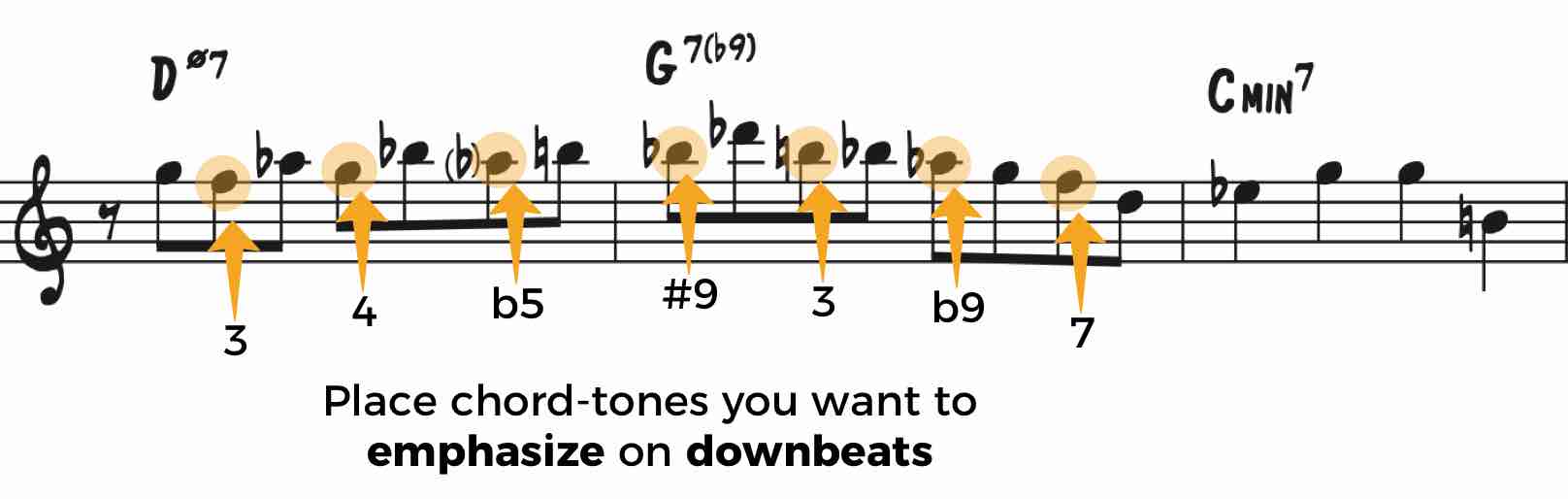

Now, take a look at how Dexter outlines the exact chord sound he wants to communicate over both the ii and the V7 of the minor ii V7 by placing specific chord-tones of each of the chords on downbeats.

Notice how he uses the other notes in the scale to lead into these essential chord-tones, so notes like B natural on the D half diminished, he doesn’t emphasize. He puts it on an upbeat leading into the #9 on G7

This care is crucial to take when using the Diminished Scale.

If you have a clear idea about what chord sound you’re going for and can easily place those chord-tones on the downbeats in your lines, then you’ll have success with this scale.

LINE #9 – DIMINISHED SCALE ON V7 (@2:55)

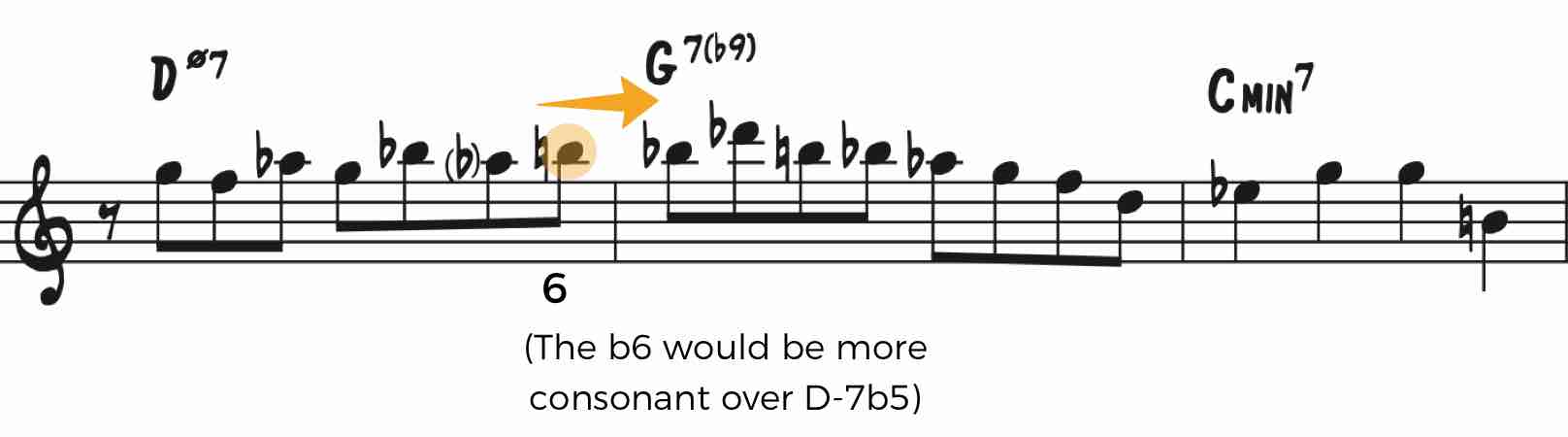

Now, Dexter not only applies the Diminished Scale to the full minor ii V7, but he also applies it to just the V7 chord, as shown in this beautiful line…

Why you’d never think of it: Again, he’s not just applying a diminished scale pattern, or mixing up the notes of the scale and hoping for the best.

He’s playing close attention to which notes he puts on the downbeats because he knows that this is what will communicate the chord sound he’s after.

To start applying the Diminished Scale on the V7 chord, start to be more aware of the notes you’re placing on the downbeats and understanding what type of altered dominant chord sound you’re communicating through this.

For instance, Dexter clearly communicates a V7b9 sound here by placing the 3-5-7-b9 on the strong downbeats 1, 2, 3, and 4.

Notice, just like he made sure not to put the B on the downbeat of the half diminished chord in the last line (the natural 13th of the half diminished chord), in this line he uses the E natural, the natural 13th of the V7 chord, on the upbeat as a passing tone (really a pick up not) into the dominant 7th, F.

And this is the care I’m talking about when using the Diminished Scale.

He doesn’t want to communicate that natural 13th in the overall chord sound here, so he places it in a particular place to make this happen.

If you’re going to use the Diminished Scale, this chord-tone awareness is absolutely essential.

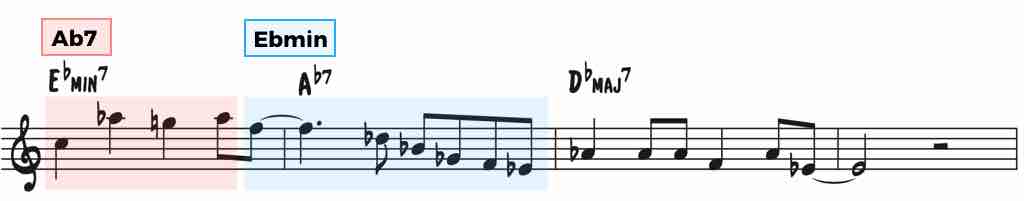

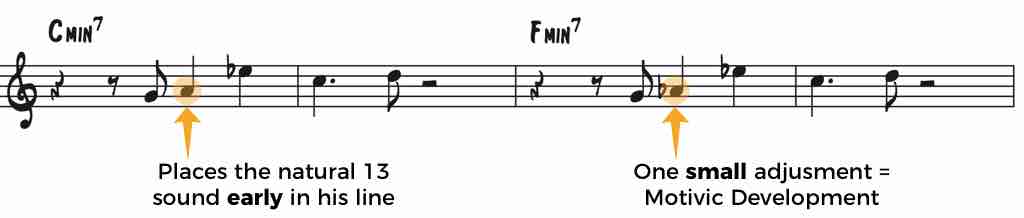

Simple Motivic Development

Motivic Development is a hot topic in jazz education and it might sound complicated, but it’s a whole lot easier than you might have you thought…

The final 3 Dexter Gordon lines we’ll look at depict how motivic development, while powerful, is just a fancy name for a simple technique.

LINE #10 – ONE NOTE CHANGE (@2:05)

Motivic development sounds like it would be difficult for beginners or inexperienced players to start using in their solos, but the truth is, it’s one of the easiest improvisational technique to implement, if you know how…

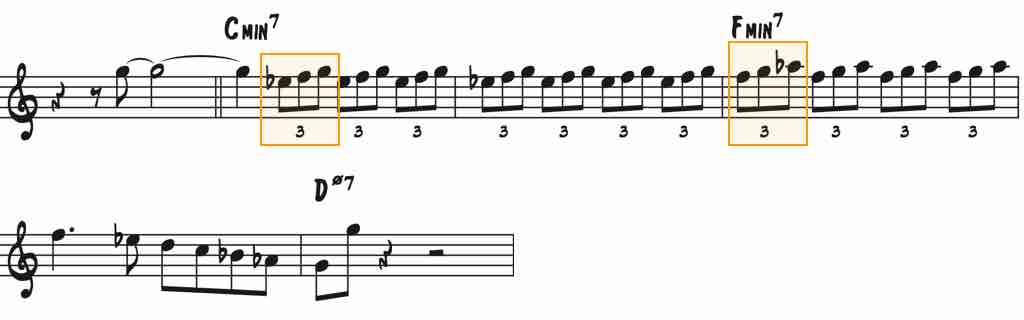

Listen to the idea that Dexter plays over C minor. And then notice that he plays almost the exact same idea over F minor.

This line is a great example of how easy a motif – a short & strong musical statement – can be developed in your solos.

Why you’d never think of it: When you try to develop a motif right now, you probably approach it in a way that is way more complicated than it needs to be.

Don’t overthink it! Motivic development is nothing special…

- You play a motif – a short and strong musical statement, usually consisting of a strong rhythm, interesting interval, or unique sequence of notes…

- And then you develop it!

To start using simple motivic development, observe how Dexter places the natural 13th early in his line (something we talked about previously) and then modifies this single note later to make the motif fit over F minor.

That probably seems pretty easy, but the key is to know what notes are in common between the two chords and what notes are different. And to be able to access this information without thinking.

Do this work in the practice room and make sure to figure out where the great spots within a tune are located to use this easy type of motivic development.

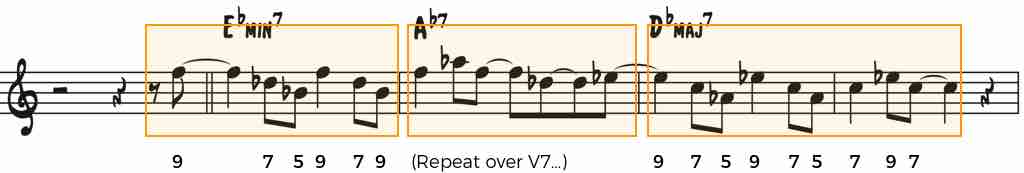

LINE #11 – ARPEGGIO AS A MOTIF (@3:46)

When it comes to motivic development, one of the main hurdles is coming up with a solid motif in the first place…

Well, an easy way to think of a good motif is to pair an arpeggio with a well-defined rhythm.

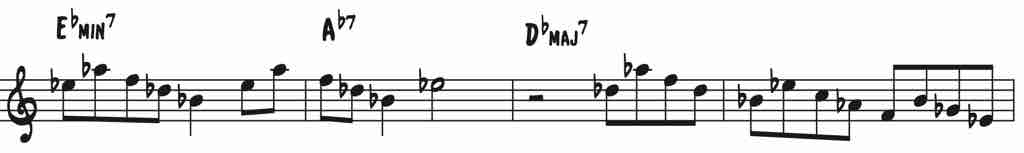

In this next line, Dexter does exactly that. He takes an arpeggio and pairs it with a strong rhythm over and entire Major ii V7 I.

Why you’d never think of it: Most people use an arpeggio for a beat or two as part of their line and move on. It never occurs to them that they could repeat an arpeggio in a rhythmic way to use it as a motif.

And they don’t think of using just a piece of the arpeggio, like the 3-5-7, or 9-11-13. You don’t have to stick to 1-3-5-7 of a chord, or always use four notes.

To start using arpeggios as motifs, first think about the chord-tones of the arpeggio you want to use. Then think about the direction you want to play them in.

In this line, Dexter uses the 5th, 7th, and 9th of an Eb minor arpeggio, but plays them in a descending fashion…

Then, once you know what part of the arpeggio you want to use and which direction you’re going to play it in, make sure you’re using a well-defined rhythm.

In this line, Dexter utilizes a quarter note followed by two eighth notes.

Does this rhythm sound familiar?

Take a listen to Night in Tunisia, and pay attention to the rhythm right before the solos just before a minute in, and you’ll hear exactly where Dexter got this from…

Remember, a well-defined rhythm does not need to be complex! It can be a simple combination of quarter notes and eighth notes, so no need to over think it.

And if you can’t think of one, just steal one from a tune, just like Dexter did!

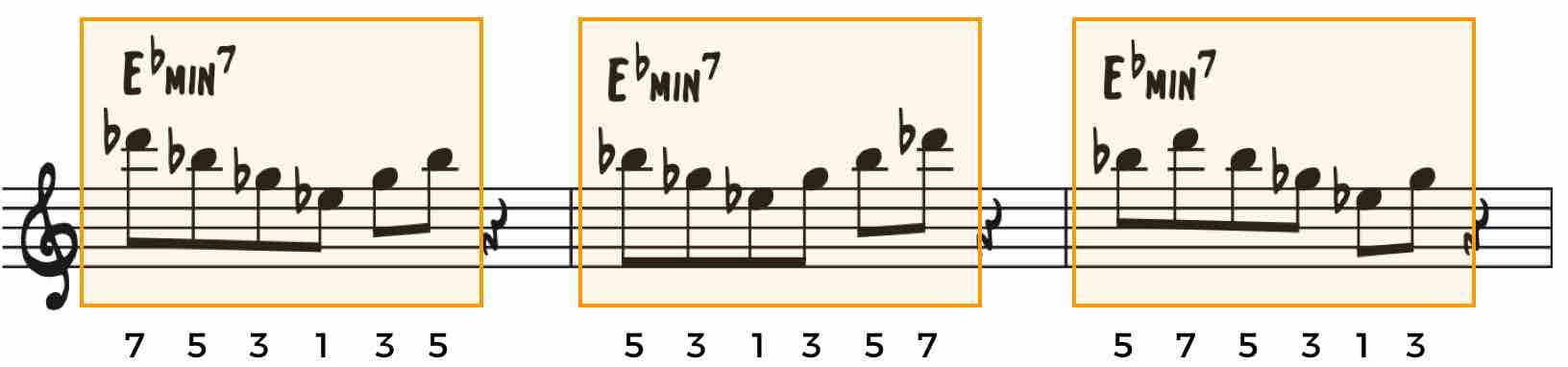

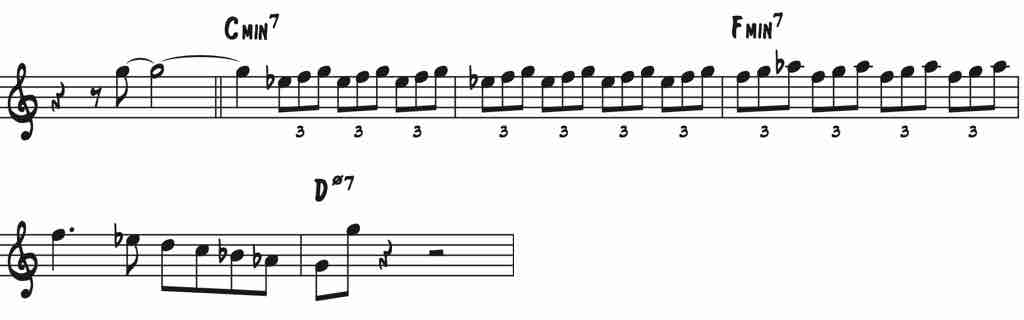

LINE #12 – TRIPLET SCALAR MOTIFS (@3:57)

So we’ve talked about using a piece of an arpeggio as a motif, but another excellent and easy way to make a motif is to use a piece of a scale.

In this line, Dexter takes the 3-4-5 of a C minor scale, repeats it using a triplet rhythm, and then moves the motif up a whole step while modifying it to work over F minor.

Why you’d never think of it: Most of the time you probably tend to use triplets as a springboard into eighth notes, a very Bebop inspired technique.

That’s usually the standard way that jazz musicians think about integrating triplets into their lines, so you might not naturally think of repeating a triplet idea like this over and over.

And then, sequencing it up a whole-step, and adjusting it to fit over the iv minor chord is genius.

To start using triplet motifs in your own playing, practice repeating a triplet idea a few times in a row and see where it leads you. Adjust it as you move through the chord changes to accurately reflect the harmony.

Then, start to explore with various directions and combinations of notes…

For example, Dexter uses the notes 345 in an ascending fashion, but why not try 543 in a descending fashion? Or, perhaps use other chord-tones like 123 or 567…

There are endless possibilities when it comes to triplet motifs, so don’t forget about them when you begin your journey into motivic development.

Learning From Dexter Gordon on Blue Bossa

Well now you have 12 Dexter Gordon lines that for the most part, you probably wouldn’t have come up with on your own.

We went over a TON today! Here are the concepts we looked at:

- How to use the 13th on minor

- How to play interesting triad shapes

- How to apply shapes over the ii V7 progression

- How to effectively use chromaticism

- How to insert octave leaps into your lines

- How to change your ii V7 perspective

- How to change up your arpeggio note-groupings

- How to use the Diminished Scale over a full minor ii V7

- How to use the Diminished Scale over the V7 chord

- How to simplify motivic development

- How to use an arpeggio as a motif

- How to use triplets in your motifs

If you take this information, practice it, apply it, and integrate it into your own jazz improvisation approach, this lesson should keep you busy for quite a while!!

As you see, there are so many answers to all of your questions on the recordings of the greats, and especially within a Dexter Gordon solo. He lays everything out in a clear and defined way that’s easy to learn from.

Have fun studying Dexter on Blue Bossa and expanding your improvisational techniques well beyond the normal approach!