It’s late. I’m exhausted. Been out all night at the jazz clubs and I just want to get home. I hop in the first taxi I see and get on my way. I’m listening to the radio and I hear something that sounds familiar. Trane? I know it’s him. His sound is unmistakable. But what album is this? What tune? I know every album, don’t I? This is so awesome and I’ve never heard it before?!?!?

Shazam.

Must get Shazam out now. If I don’t know what this is, it’s going to drive me crazy for the rest of my life!!

Sending…sending….sending….

“Transition. John Coltrane.”

This was the first time I heard the tune Transition from the album of the same name. It absolutely blew me away. It was a combination of “Oh my God what is this!?!?!” And, “This is the most insane %$^# I’ve ever heard!!!”

I knew that one day, I’d have to dig into it and see if I could make sense of anything he was doing.

And many people have done this before. I’m hardly the only tenor player obsessed with Trane. But I wanted to unravel this mystery for myself because when you study something yourself, you make sense of it in your own way instead of taking someone else’s word for it.

And if you listened to the video, you know that today, we’re not looking at ii Vs or how to craft a beautiful melody, oh no no no…

We’re looking at in-your-face, hyper-speed runs, that are NOT easy to make sense of.

But wouldn’t it be awesome if you could make sense of these runs? And wouldn’t it be even cooler if you could actually use some of the tactics that John Coltrane used to come up with these insane melodic bits?

This isn’t going to be some technical analysis or proof of what Coltrane was doing. To be honest, I wish I knew. I wish that I could peek into Coltrane’s notebooks and see for myself, or better yet, talk to him and ask him exactly what he was thinking to come up with this stuff…

But the closest I will ever get is right here. With the recording. Deciphering for myself what he possibly could have been thinking about and practicing.

And what I found was unexpected…

Defining a Macro Structure: Using target notes in a brand new way

When you’re moving at lightening speed, what communicates chord structure?

Teachers will tell you, with good reason, to place chord-tones on downbeats. And, while this is an incredibly over-simplified view of how to play jazz, putting chord-tones on downbeats will communicate the underlying chord-structure.

Now, when you’re moving really really really fast the way Trane is when playing Transition, the “chord-tones on downbeats” thing becomes even more paramount, because you have to communicate an underlying chord-structure while moving really fast.

But what if you wanted to impose your own structure rather than play the tune’s chord-structure?

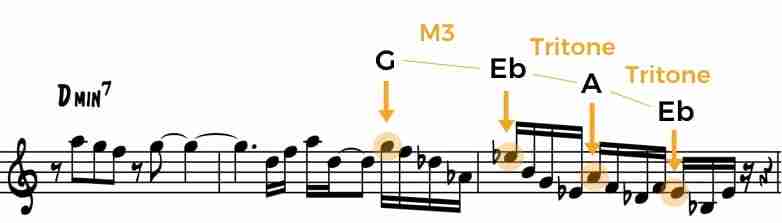

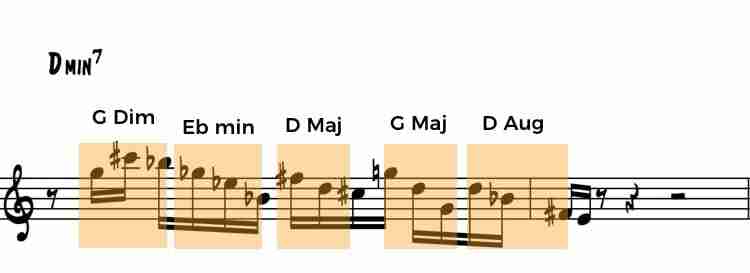

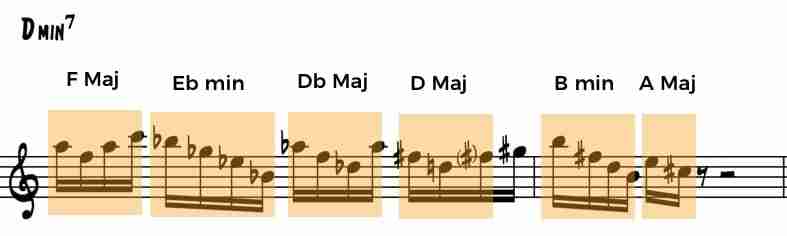

Well, you would structure the notes you place on downbeats. And that is exactly what Coltrane does, but it’s not easy to figure out. Take a look and a listen to the phrase below (1:04):

Before I explain how this concept works, take a shot at it. Given the idea I was just talking about, can you see how he’s structuring these notes?

How bout this phrase (2:17)…

Ok, I’ll help you out. After all, that’s why I’m here 🙂

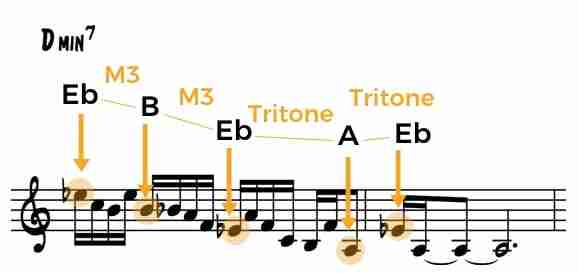

In this first phrase, and all the other phrases we’ll look at, he’s structuring each 4 note group by using whole-steps, major thirds, and tritones to separate them – these are all the intervals within a whole-tone scale, likely not a coincidence.

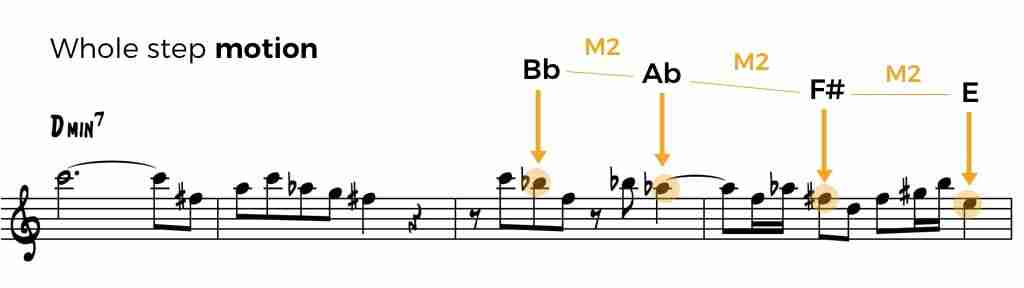

We’ll get more into what this means later, but looking at an example is the best way to start to understand this concept (1:04):

When Coltrane moves out of the key, D minor, each note on the downbeat is a “target note” and these target notes move in intervals found in the whole-tone scale: whole-steps, major 3rds, and tritones.

Most of the time, “outside” playing (moving outside the key center and outside of the chord changes) is actually highly structured. It’s not random, but highly organized.

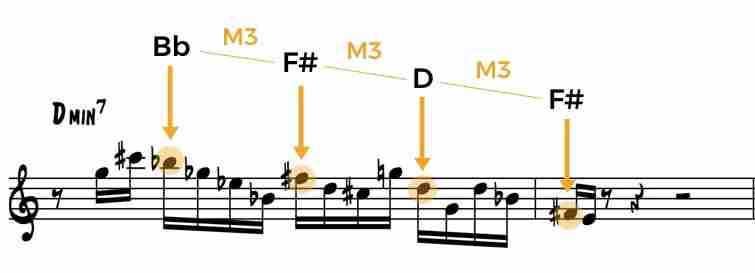

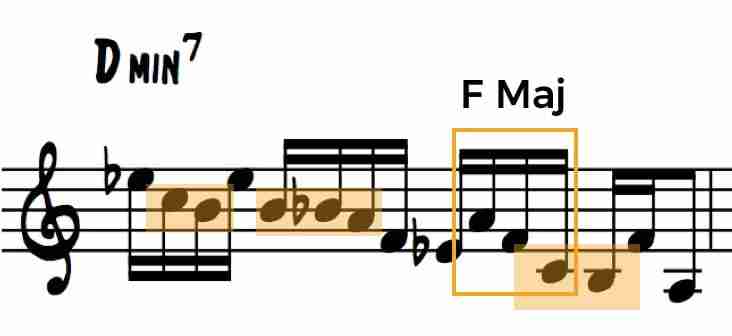

Here’s another example of this idea. Each group of 4 notes is spaced out by a major 3rd (2:17):

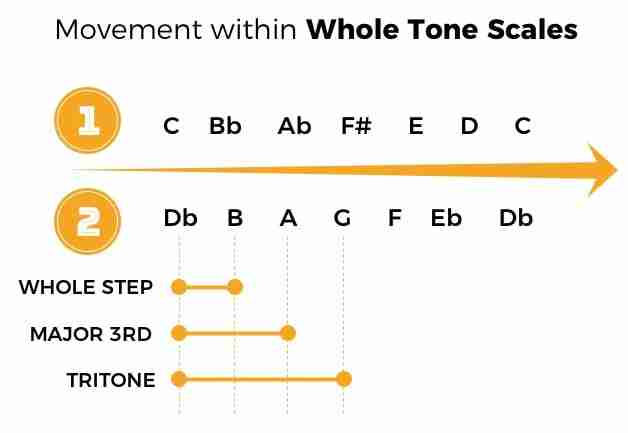

So why did I mention the whole-tone scale and how are these intervals related to it?

It’s not really the scale that’s the focus here, he doesn’t even play the scale, but he uses the intervals contained within it as part of his “macro-structure” concept.

You see, a whole-tone scale (A scale made of all whole-tones) only has three possible intervals (excluding inversions). From any given note, moving to another note, the space between them can only be:

- A major 2nd (a whole step)

- A major 3rd

- A Tritone (augmented 4th/diminished 5th)

There are only 2 whole tone scales. One starting on C and one on Db. See how the intervals are restricted within the scale?

Using these intervals, Coltrane spaces out his groups of notes, and these target notes that lie at these intervals hit on the downbeats. By doing this, he suggests shifting tonalities.

Go ahead and listen to this (3:04):

Here, on each downbeat he places a note that is a whole-step below the previous. Each time he descends a whole-step our ear hears the contrast from the previous note, and shifts to a new tonality.

Now, it’s not the exact “key” or “tonality” that he’s shifting to that matters. What matters is that our ear hears the structure of the major seconds very clearly, which creates a clearly defined sense of shifting to somewhere new at a regular rate.

But what about when Coltrane does not shift by intervals from a whole-tone scale? What else is he doing?

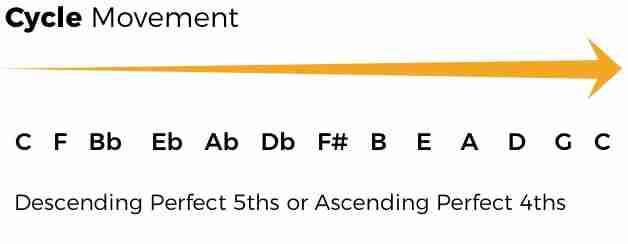

Sometimes, Coltrane will mix in another interval with the intervals from a whole-tone scale. And, not surprisingly, this interval is a perfect 4th up, the same as a perfect 5th down – something we call Cycle Movement.

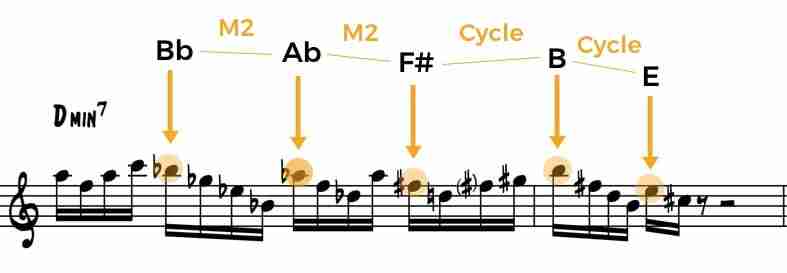

In this next line, Trane uses target notes from whole-tone, and mixes in a couple intervals using Cycle Movement (3:12):

Cycle movement is always an option because our ear is so used to it. Think about it. Every ii V, Every iii Vi ii V…

It’s all Cycle Movement. And mixing in this clearly defined structure works well, especially moving toward the end of a line, or a resolution point as seen above.

Now this is not an exact science, but looking at all these lines, there is structure to them. They’re not random. It’s not as if he goes on autopilot and plays whatever.

They sound a certain way because they’re structured a certain way.

But what is doing between the target notes?

Enter triads and chromaticism.

Triadic and Chromatic Craziness: Filling in the Gaps

Many people have examined Coltrane’s crazier playing like this before and one common theme seems to be the use of triads. People will analyze a Coltrane line, see the triads, assume that’s what makes it great and move on.

Well, the triads are obviously a huge part of what he’s doing. But as we just went over, the macro structure of his lines seems to dictate how he arrives at these triads.

The exact triads used within this solo are fairly unpredictable, however the structure of target notes does not seem to be. So combining the two concepts, we can aim for our target notes and use triads to “fill in the gaps” between them (1:04).

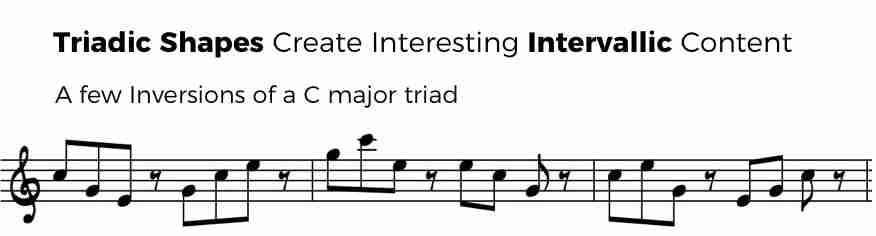

These are definitely triads and they come to us in various inversions. These inversions create well-defined shapes with great intervallic interest.

You don’t even necessarily have to use all 3 notes of the triad, or be super clear with it. The overall macro structure of the downbeats takes care of the strength and direction of the line. The triads simply fill in the rest of it with interesting, seemingly random intervallic content (2:17).

But wait a minute…what’s that “C#” doing in there?

Let’s be real. Some of what Coltrane was doing is not going to fit into some neat little box because he was so free. He had complete melodic freedom. But, our goal is not to determine what he was actually thinking, but to make use of the information in a way that we can add it to our playing.

And looking at places like this, instead of using triadic content for our “filler material” we can use chromaticism. Listen again to this line and hear that chromatic note (2:17).

Sometimes Trane will stick to using just triads, but other times he’ll be much heavier on the chromaticism (2:21):

And take note that even when he’s using chromaticism as his “filler content,” the downbeats still outline the strong intervallic structure from a whole-tone scale, in this case, major 3rds and tritones.

So now you know that you have two tools at your disposal. Both triads and chromaticism. Here’s another line where Coltrane uses only two notes from most of the triads. Notice how even just using two notes is effective (3:04).

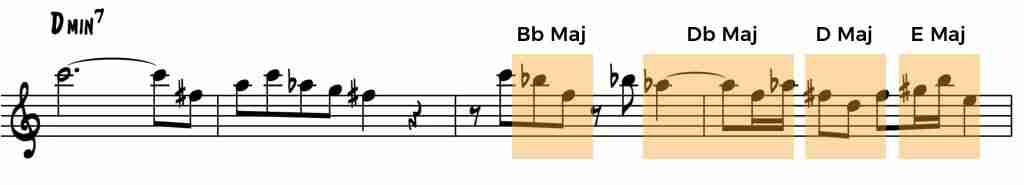

And in this line, he outlines triads almost exclusively (3:12).

Starting to understand this explanation behind the method of his madness?

Believe me. This stuff is hard. And it’s even harder to actually integrate into your playing in a musical way.

But start slowly, and over time, the relationships will begin to make sense to you.

Here are a few exercises to get you started on this path…

Triadic Shifting Exercises Through Whole-Tone Intervallic Motion

Gosh, that’s a mouthful…

But, that’s essentially what you’re doing. You’re shifting through suggested tonalities by using triads that are outlined by intervallic motion from a whole-tone scale.

Don’t be scared off. It’s not as scary as it sounds.

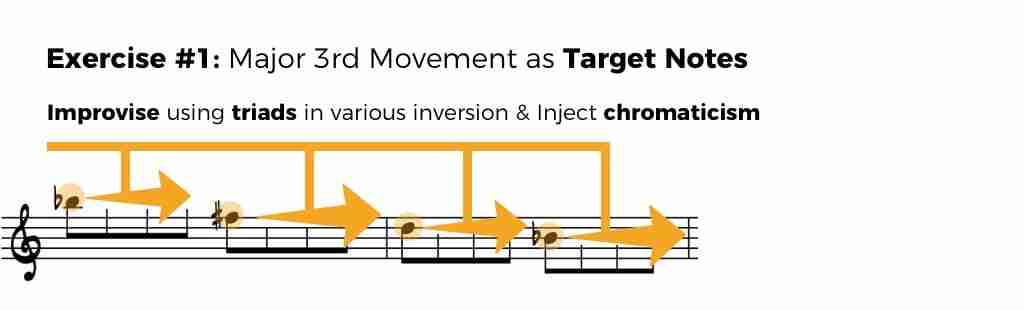

The first step toward using these ideas is to become comfortable using target notes from the whole-tone scale.

In Exercise #1 your goal is to hit the target notes a major 3rd apart on each downbeat. You fill in the gaps using either triads or chromaticism.

While this exercise may look easy, It’s very difficult. Start by playing this exercise with no time so you can think because you’ll have to. Use each new target note you arrive at as a “1” “3” or “5” of a triad, and once you get comfortable, start to inject chromaticism into your line.

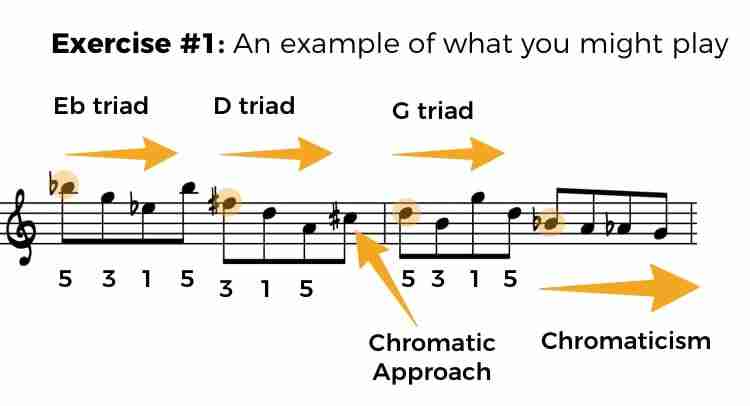

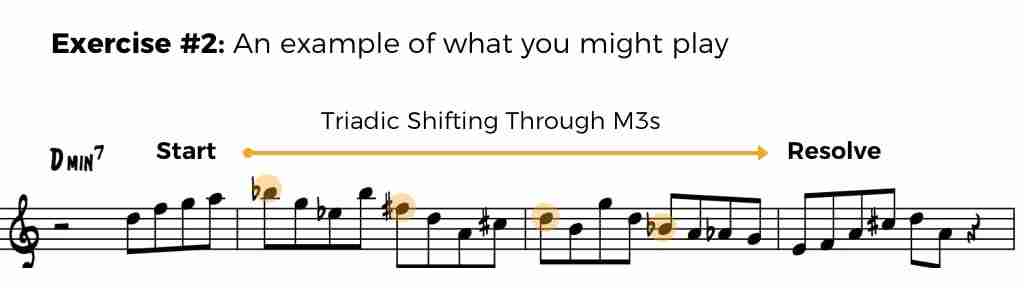

Here’s an example of what you might play for this exercise:

I repeat. This is not easy.

You could spend not days or even weeks, but months or years becoming fluent in this idea.

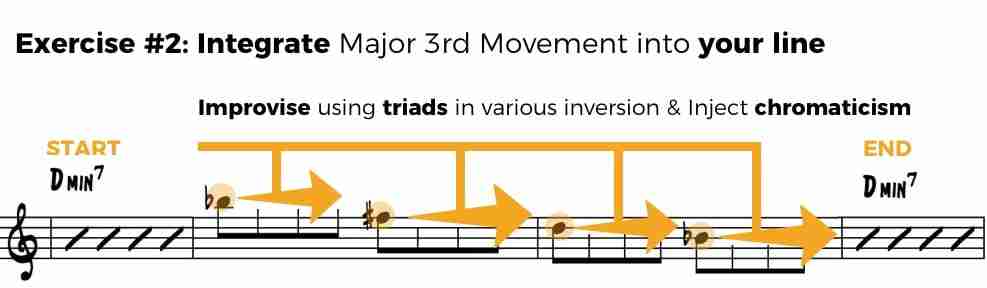

But once you have fluency with that exercise, you want to integrate the use of these shifting tonalities into a home tonality like D minor. In Exercise #2 that’s exactly what you’ll do.

This is exactly the same as Exercise #1, except you’ll start and end within the tonic key. Here’s an example of what you might play for Exercise #2.

Learning to weave between the home key and the shifting keys and back again is a huge skill. The tricky parts are still with Exercise #1, so if you’re interested in using these tactics, make sure you spend most of your time mastering that one.

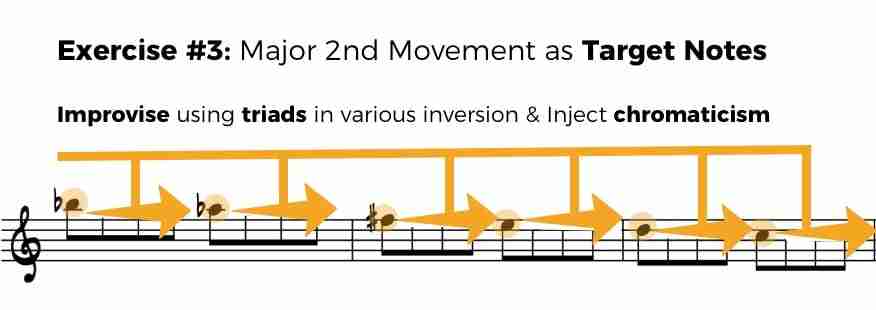

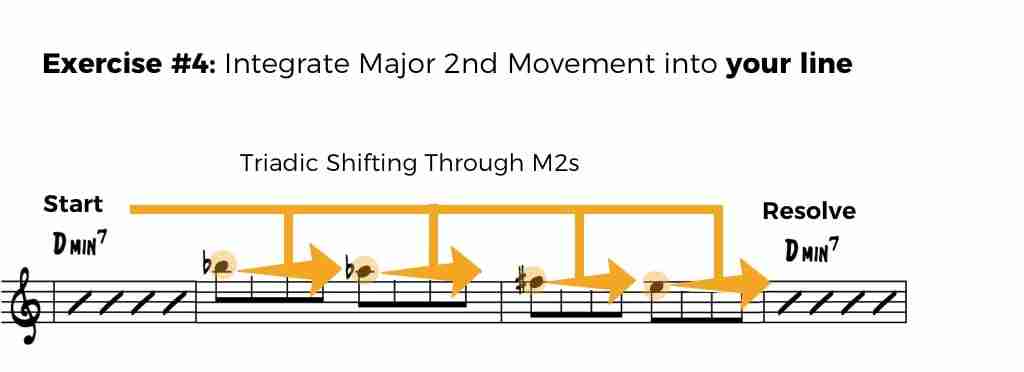

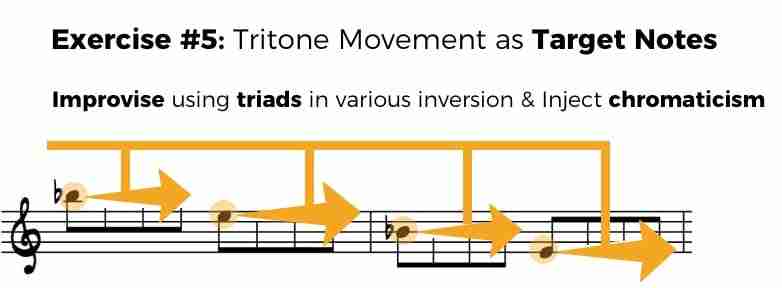

Besides moving by major 3rds, we can also move by whole-steps or tritones as we saw Coltrane do.

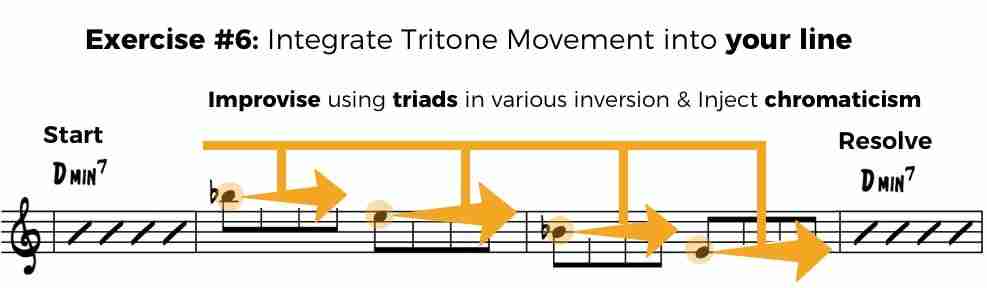

In Exercises #3 and #4, and Exercises #5 and #6, you’ll do what you did in the previous 2 exercises, but using major seconds and tritones as your macro structure of target notes.

First with major seconds (whole-steps)…

Next with tritones…

This is just the tip of the iceberg. There’s so much you can do with this concept and feel free to change or interpret the information differently. This is just one way to understand what Coltrane is doing and make use of it, but there are many other interpretations.

The important thing when learning a new device like this is to remember that it’s not a replacement or substitute for everything else you’re learning. It’s just another tool to add to your toolbox – another perspective.

Is it advanced? Yes. Is it fairly difficult. Yes. But so are ii Vs and playing Rhythm Changes. It’s all jazz and it’s all at your disposal to help make you a better musician.

Have fun with these Coltrane ideas and I hope Transition inspires you as much as it inspires me!