Have you ever tried to play over a so-called easy tune, only to find that it’s not actually that easy? All Blues, one of the most incredible tracks from the legendary Miles Davis album Kind of Blue, is commonly referred to as an easy tune throughout jazz education, yet this seemingly simple composition contains more challenges than most people realize…

So why do people believe All Blues to be such an easy jazz tune?

Simply put, when you look at the tune in The Real Book, it looks easy – after all, it’s just a blues. But what are people missing about this tune that makes it more complex, and more importantly, why do most people struggle to solo well over All Blues if it’s supposed to be easy?

To understand why people believe this tune should be easy, you first have to think in terms of how they’re measuring easiness, which seems to be based upon:

- The basic form of the tune – it’s “just” a blues

- The number of chords in the tune – it only has 4 chords

- The moderate tempo – typically it’s not that fast

These points lead someone who glances at the facts to quickly jump to the conclusion that this jazz standard is trivial, that anyone could easily play a great solo on it…

But, here’s what they’re missing…

- The unfamiliar key – most blues tunes are not in G

- The unfamiliar time signature – most tunes are not in 6/8

- The unfamiliar dominant chords – the alt dominant chords in bars 9 & 10

These 3 factors add quite a bit more challenge to the scenario. And, not to mention…when’s the last time you heard a player besides a professional jazz musician sound amazing over a blues??

I don’t care what anyone says, the blues, although conceptually simple, is by no means easy to actually sound good over.

Put all of these points together and you’ll quickly realize why All Blues should never be categorized as an easy tune, yet so much of the time, it is…

In fact, for years I can recall going to jam sessions and masterclasses where the teachers or students would call this tune and without fail, the unfamiliar key and time signature greatly limited everyone’s improvisation.

And there always seemed to be one place in particular where literally every single person sounded like they were lost – their lines stopped being coherent and no one knew what to do…it was clear that during this particular part of the tune, everyone was faking it…

All Blues – The 2 bars that mess everyone up

All Blues is a beautiful composition.

Its apparent simplicity, as we just talked about, makes it accessible to even the most casual listener, yet it provides a perfect canvas for the most intricate improvisation to occur.

And when you listen to All Blues, it doesn’t matter who you are, whether your ears are well trained, or you’re just a jazz fan…measures 9 & 10 naturally pop out at you because of the inherent tension in the chords as contrasted with the rest of the tune.

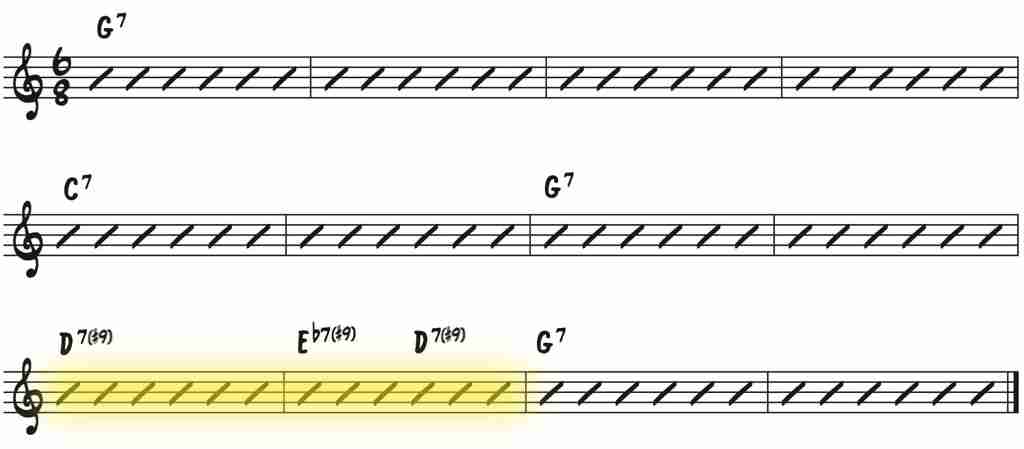

I’m talking about these two measures…

And these my friend, are the 2 bars that mess nearly everyone up when trying to take a solo on All Blues.

What’s so difficult about these two measures? Is it that these chords are actually that difficult, or might it be that we’re thinking about them in the completely wrong way?

When most people get to these two bars, they’re thinking about 2 things:

- A chord symbol they’re looking at

- A scale that the chord symbol translates to

If you’re approaching these measures in this way, you’re already starting off on the wrong foot because chords are not symbols or scales…they’re sounds.

The chord symbol attempts to visually encapsulate the sound, and a scale attempts to translate the chord into a horizontal string of consonant notes, however, without being able to clearly hear the chord sound in your mind, chord symbols and scales will leave you searching in the dark for something coherent to play.

So the first thing to do is to change your meaning of these chords from just visual elements, something you see, to aural elements…something you HEAR…

Hearing the altered dominant chords in All Blues

Relying on chord symbols and scales to improvise jazz without actually knowing what the chord sounds like, how it functions, and generally how it works, is a lot like painting by number…

You’re blindly following a formula that approximates the results of your heroes, without having a true understanding or connection with what’s actually transpiring.

But not to worry…training your ear, to hear these altered dominant sounds is easy even if you’ve never done it before.

First, let’s find a place where the rhythm section is clearly laying down these chords so we can easily hear what’s going on.

Bill Evans plays the first altered chord (D7) very clearly right here…

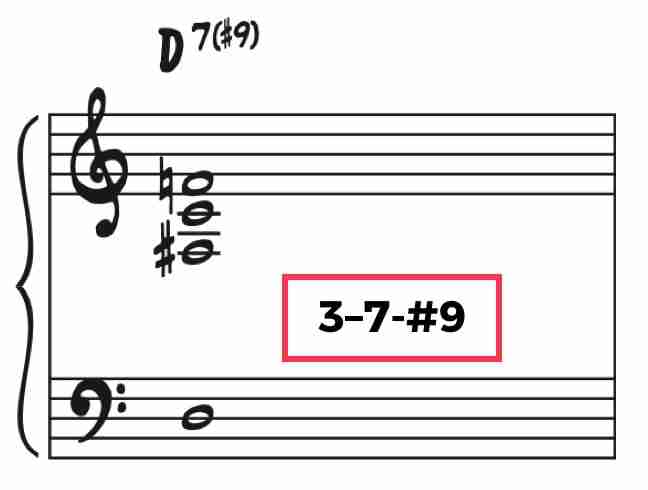

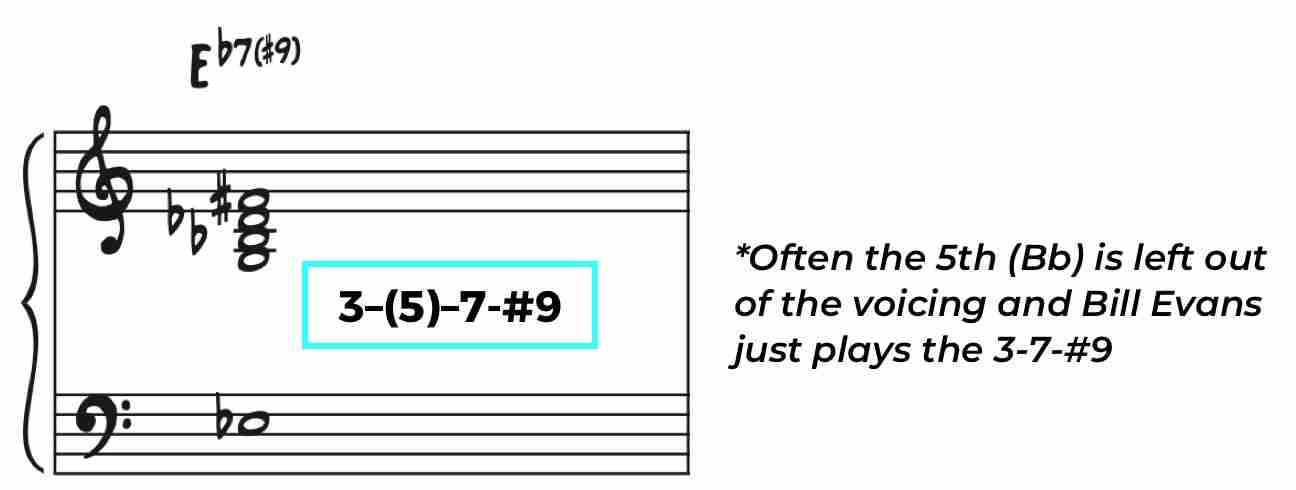

And if you listen closely, you can hear that his voicings throughout the changes for this chord tend to include a #9 along with the 3rd and 7th, and occasionally during solos, he might add in the #5.

Keep in mind though, during the melody it’s just the 3rd, 7th, and #9 in the chord voicing, and Miles is actually sustaining the natural 5th of the chord.

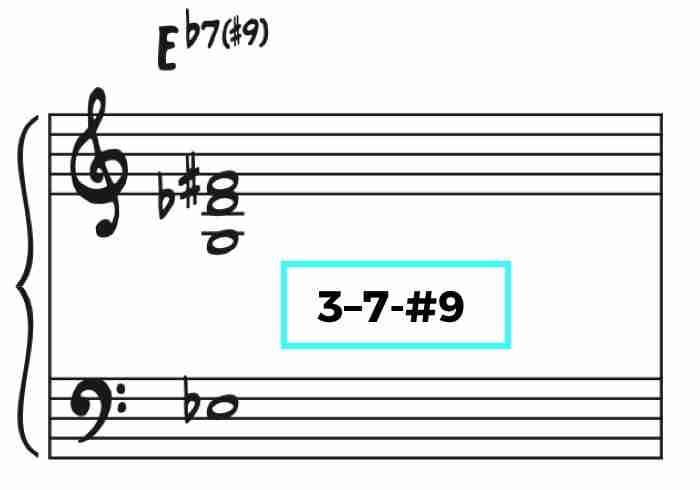

So an easy voicing for you to play at the piano and hear the chord would be something like this…

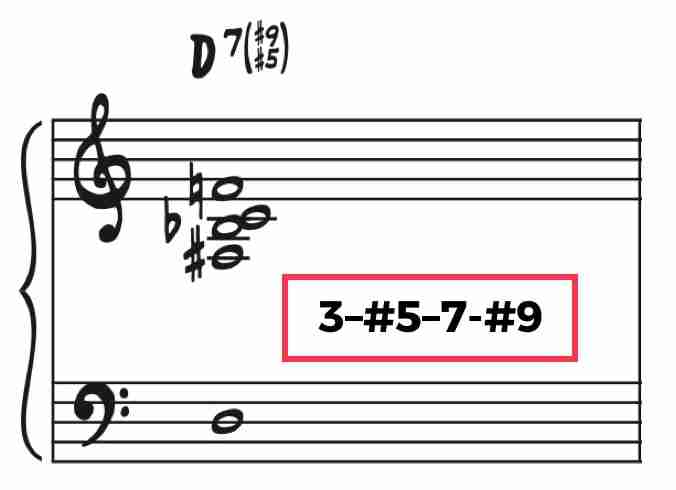

And you can also add the #5 into this voicing to get an idea of what that might sound like…

Now let’s take a listen to the second altered dominant chord (Eb7) voicing to get an idea of how Bill Evans voices this chord throughout the tune…

Throughout the entire recording, Bill Evans generally only plays the 3rd, 7th, and #9 of this chord, however he may occasionally sustain the #5 from the D7 chord (Bb) over the Eb7 as well, which would be the natural 5th of the chord.

So for the Eb7 altered dominant chord you could play this simple voicing…

And you could also add the natural 5th just to get your ear used to that sound, although like I mentioned before, Bill Evans usually leaves the 5th out of the voicing, favoring a more open chord sound.

Now just to go one step beyond this, it’s always a good idea to look for more clues about the chord sounds to make sure you truly understand what’s going on…

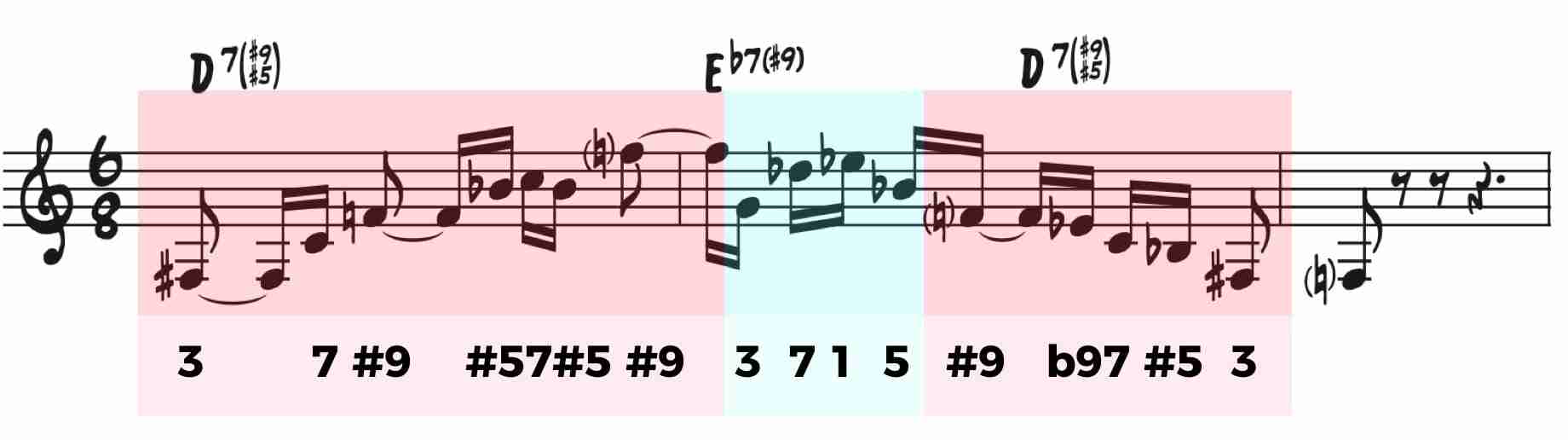

And a great place where clues lie in this tune happens when Bill Evans plays the chord voicing as a loose arpeggio when Miles is soloing…

In this example you get additional insights into how Bill Evans is thinking about and voicing these two altered dominant chords as he comps behind the soloists – It’s clear he’s using the 3rd, 7th, #5, and #9 over the D7, and notice the natural 5th on the Eb7.

Remember, much of the time, and during the melody, he’s just playing the 3rd, 7th, and #9, usually leaving the 5th of the chord out of the picture altogether, but as a soloist, we’re not just interested in how he voices the chord during the melody…we need to listen to what he does during the solos, too.

Obviously, to do all this work and figure out what chord tones you’re hearing within the voicings, you have to be able to hear these nuances. I can’t stress this enough: train your ear daily to hear these sounds. Once you have the basics down, even the most daunting of tasks becomes approachable.

So now that you have these chords at your disposal, it’s time to practice them at the piano…

Practicing Chords At The Piano

Go to the piano, or your midi keyboard, and work on playing and hearing simple voicings of these chords. Keep in mind you don’t need to be McCoy Tyner to play simple chord voicings…this is something anyone can do.

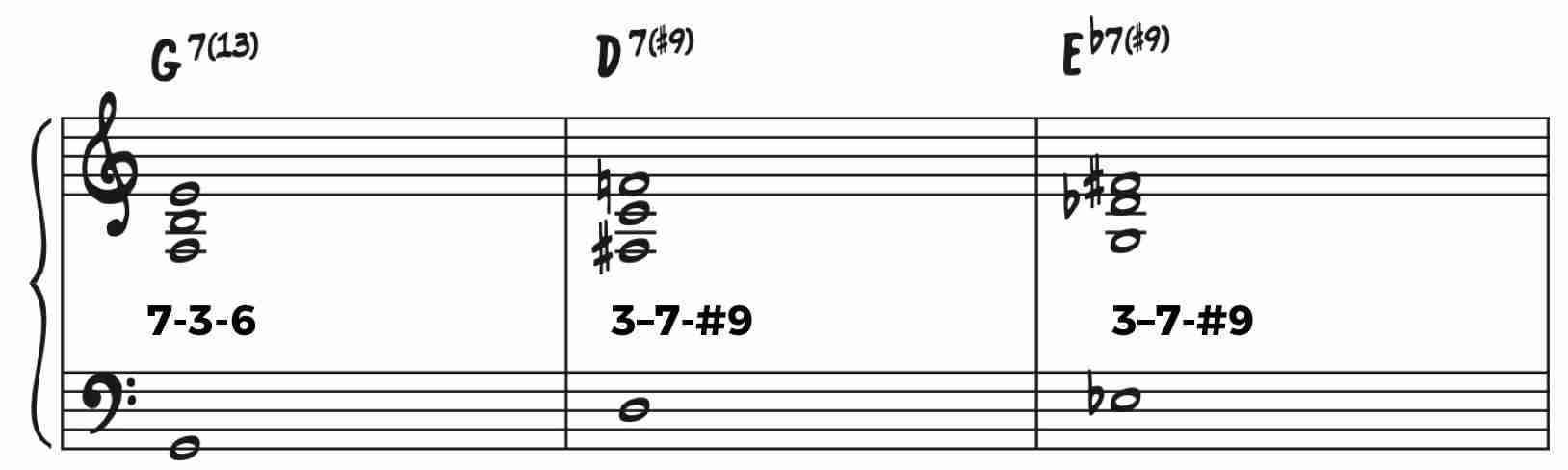

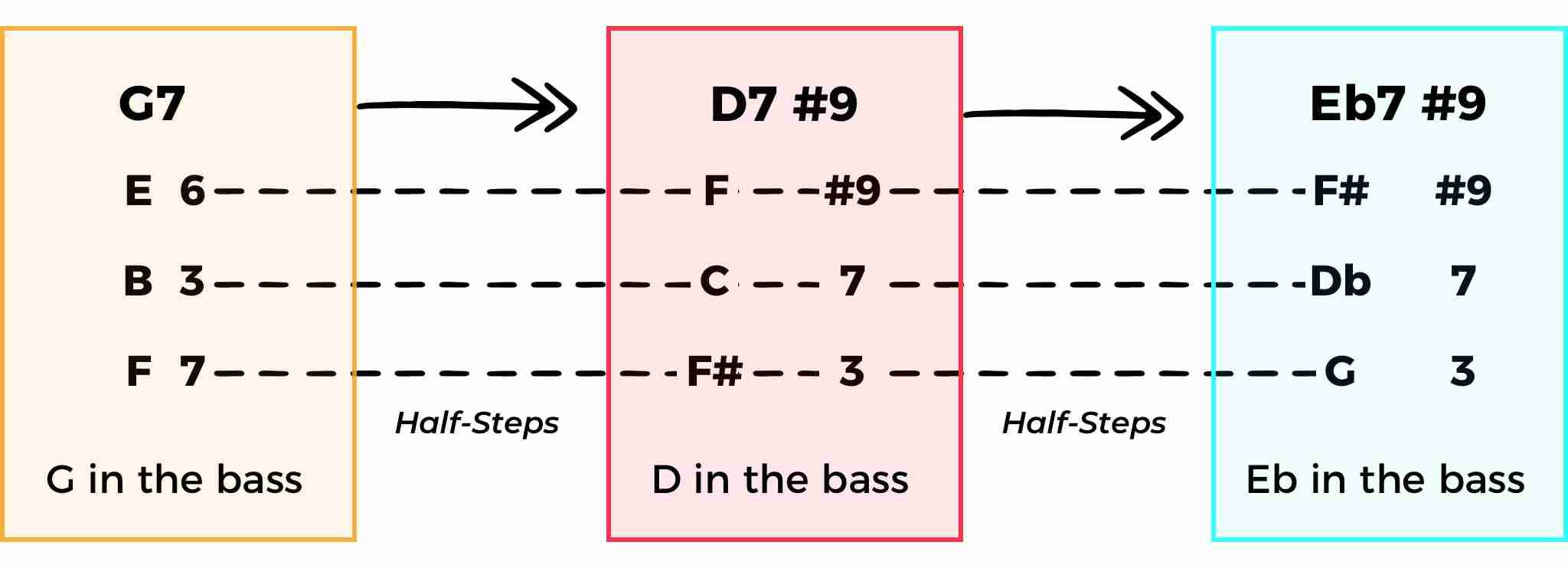

Here are the two simple altered voicings we talked about and a basic dominant chord voicing for the G7 with the natural 13th, which is the same the the 6th.

When you’re practicing these at the piano, pay close attention to the voice leading between the chord tones within the chord voicings.

Did you notice that the transitions from one chord tone to the next are half steps?

Any chords of a tune you don’t understand, these should be your first steps – Transcribing what the rhythm section is doing, how they’re voicing the chords, looking for any other clues that might help you figure out the little details, and spending some time playing the chord sounds at the piano.

Studying the chord sounds like this does two very important things:

- It helps you mentally & theoretically grasp the structure of the chords

- It sets you up for truly being able to hear the chords

Without this information, playing over a chord is largely a theoretical exercise of matching symbols to scales. We don’t want to improvise in a paint-by-number kind of way…

Remember…before chords were a symbol or suggested a scale, they were sounds…and that’s what you need to focus on and absorb.

Alright, now that you can hear these chords, we’re halfway there…now we need to build an approach to play over these chords.

Most of the time as we mentioned before, people think of the chord symbol, which then translates to a scale in their mind, and then they launch into their improvisation…

But, to play over a tune like a pro, when you think of a chord symbol, you must get beyond the scale…you need some powerful melodic techniques at your disposal.

So next we’ll dive into some of the specific techniques Miles Davis, Cannonball Adderley, and John Coltrane use to sound incredible on All Blues.

Aim for the Altered 9ths like Miles Davis

The first technique we’ll talk about is so easy that most people immediately dismiss it, yet often, it’s the simplest melodic techniques that are most effective.

Rather than trying to use every note possible in the chord sound, why not focus on the most colorful chord tones?

Miles Davis loves to do this – he constantly emphasizes only one or two notes of a chord, but these notes are chord tones with great color and meaning.

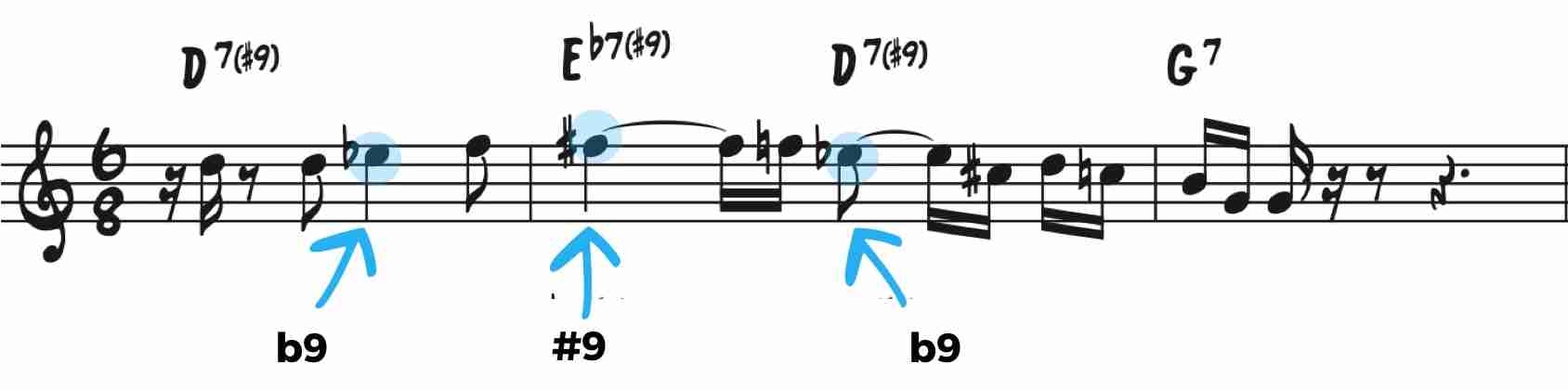

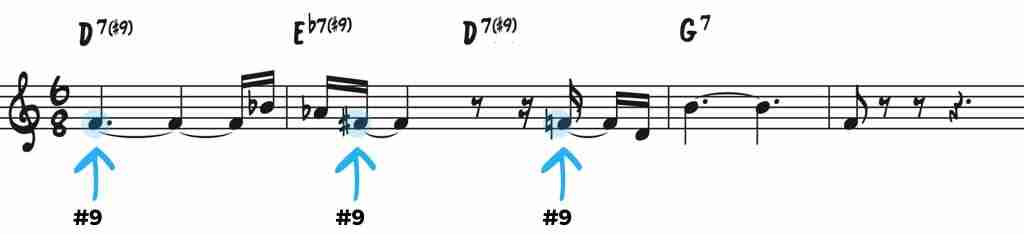

Take this phrase for example…

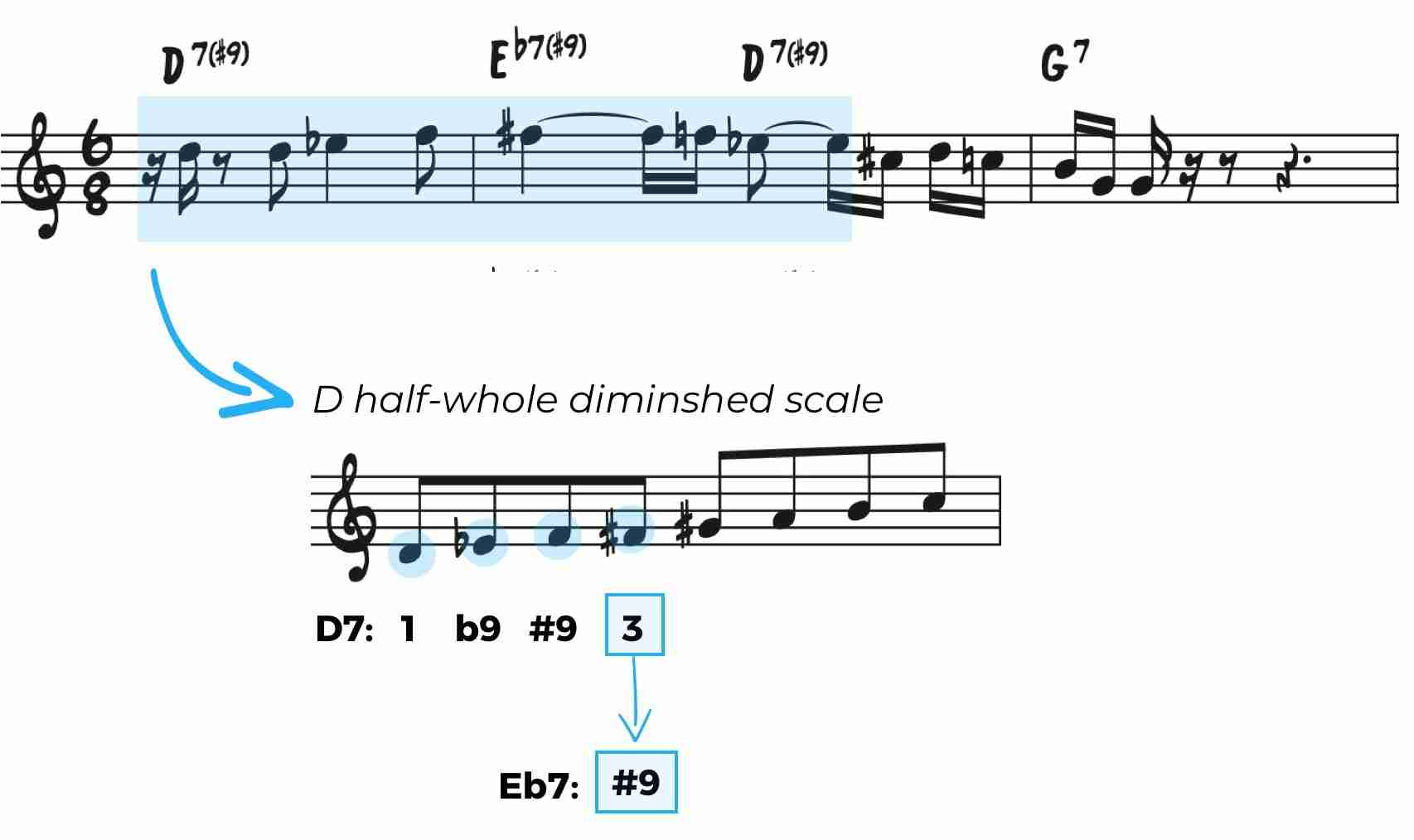

A simple melodic idea, Miles stresses the b9 on the D7 and #9 on the Eb7. And the idea has great melodic continuity because he’s leading to the b9 and the #9 by using a small piece of the diminished scale.

This technique is super powerful here because the 3rd of D7 (F#) happens to be the #9 of Eb7.

But, note that in this phrase, the scale completely takes a backseat – he’s primarily focused on where he’s placing the b9 and #9 in his line. The piece of the scale just happens to help guide him to these tensions that he wants to showcase.

Later in his solo, Miles again plays over these measures using the same straightforward tactic of aiming for the altered notes, however, this time around he chooses to emphasize the #9 on both dominant chords:

You can start using this technique right away over these altered chords. First, practice playing just the b9 on each chord in 6-8 time, then, play the #9…

And after you can easily access each of those notes, practice mixing it up between the #9, b9, and leading into to these tensions the way Miles does to make your line rhythmically interesting.

As you can see, it really doesn’t take much to craft a clear melodic line through these chords simply by aiming for the b9 and #9.

Use the colorful triads like Cannonball Adderley

Cannonball Adderley’s playing is steeped in the bebop tradition, yet he’s well aware of how to apply his bebop language to any situation.

This knowledge gives him so much improvisational flexibility because he can take anything he already knows and completely transform its harmonic meaning by using it in a new situation…

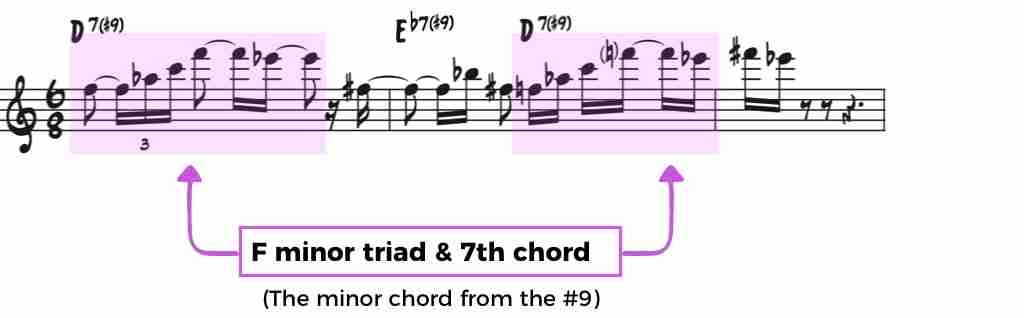

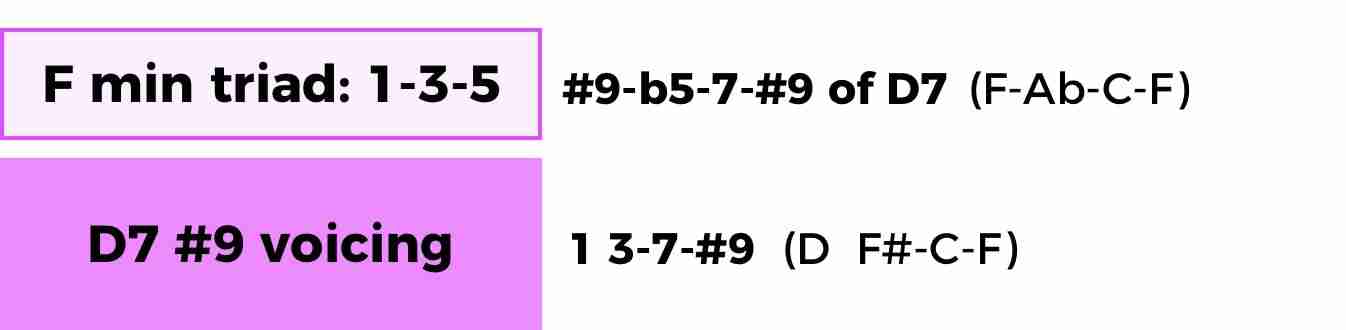

For instance, he can play a simple F minor triad, and sound incredible!

Here he’s using the minor triad from the #9 of the chord (F triad, the #9, on D7). And he also uses the 7th of the F minor (Eb), which works great because it’s the b9 of D7.

This is another easy altered dominant technique illustrating how you can think of a simple structure rather than running up and down the altered scale.

Listen to how the triad from the #9 sounds over the D7alt and try to hear how it targets specific colorful chord tones.

Whether you use the triad or the full 7th chord, it’s super easy to use…

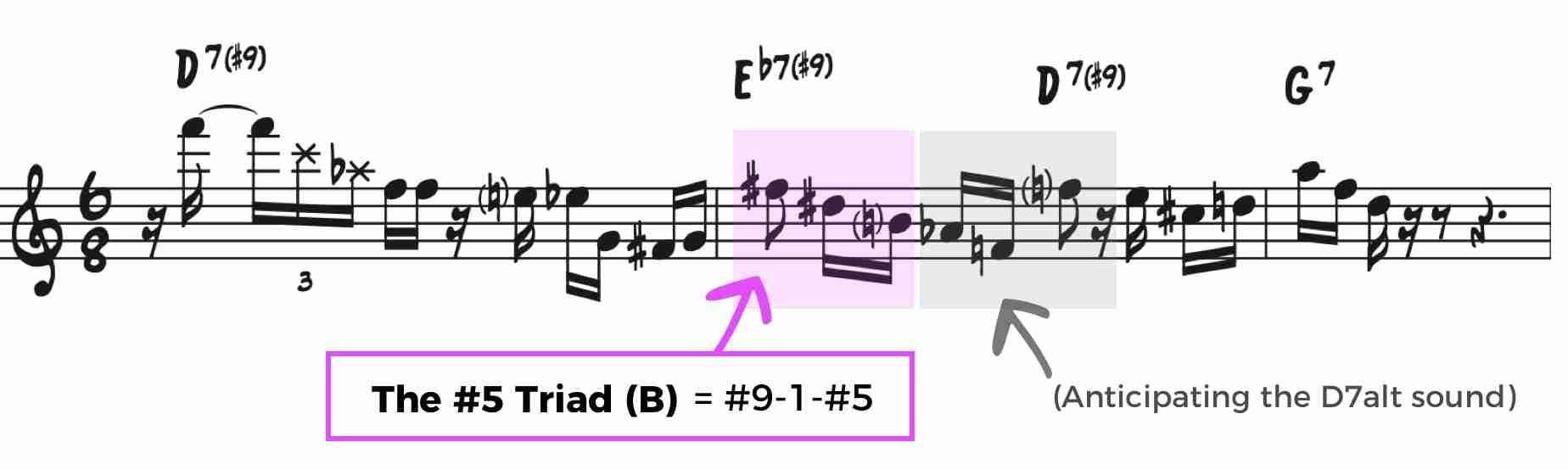

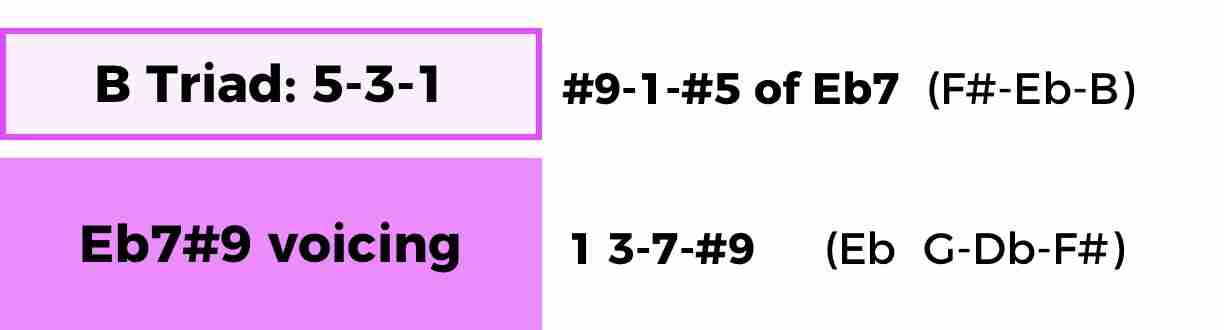

And another simple triad technique Cannonball likes to use is based upon the #5 Triad – playing the triad that’s formed starting from the #5 of Eb7 (B).

When a chord only lasts for a moment like this, using a triad for speed and clarity is a great technique to quickly communicate the altered sound. With very little effort, you highlight both the #9 and #5.

And notice that just because the chord voicing may not include the #5, that doesn’t mean that it’s not an available tension to play over this sound.

Here’s what it sounds like when we break it down at the piano…

Remember, you don’t need to go overboard and try to play every possible chord tone. It’s often better to highlight just a few as we’ve seen both Miles and Cannonball do by using simple chord tone & triad techniques.

Next we’ll look at how John Coltrane applies his musical genius to these altered chords…

Play Cells like John Coltrane

Without a doubt, John Coltrane will always come to the table with something unique. He’s constantly looking to do things slightly different than everyone else and trying to approach musical scenarios from a different perspective.

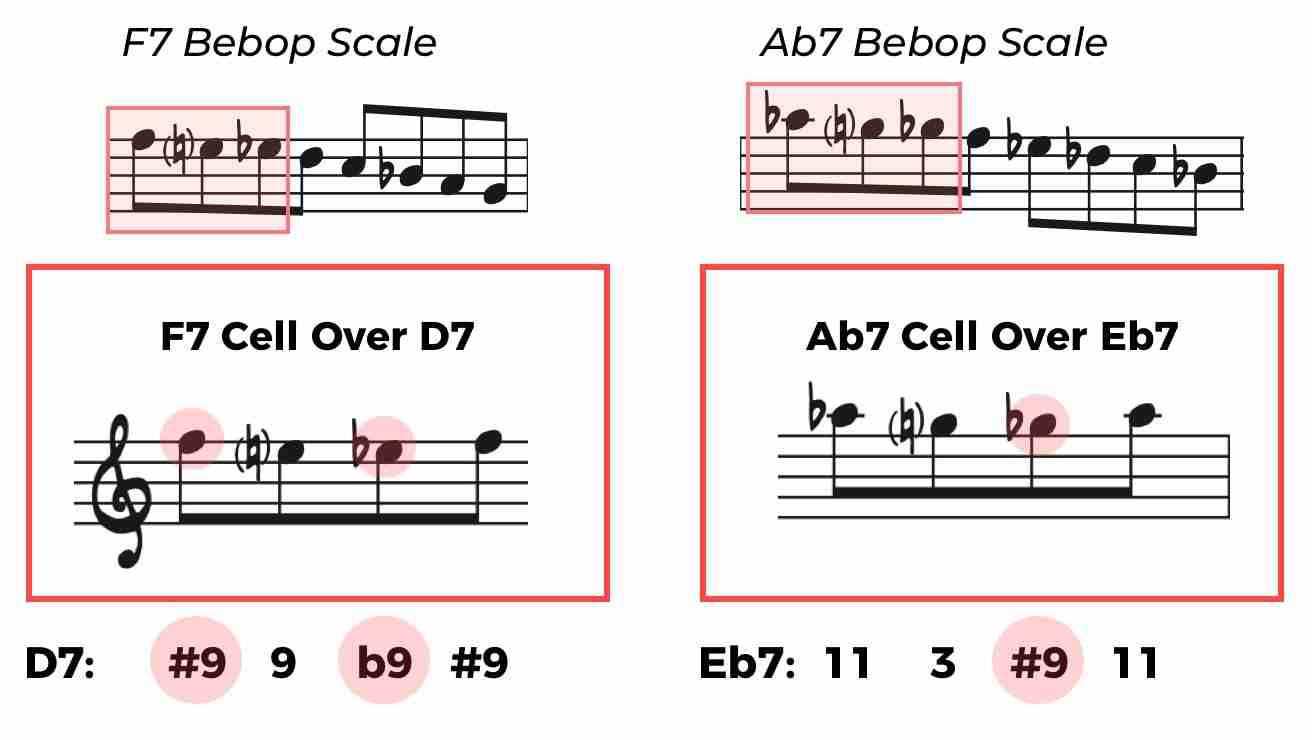

One of the hallmarks of his musical style is his use of musical cells – a group of several notes, often 3 or 4, but possibly more, that can be applied to many different chords.

When a cell that originated from one chord is applied to another, it takes on new harmonic meaning, a lot like how Cannonball placed the F minor triad over D7.

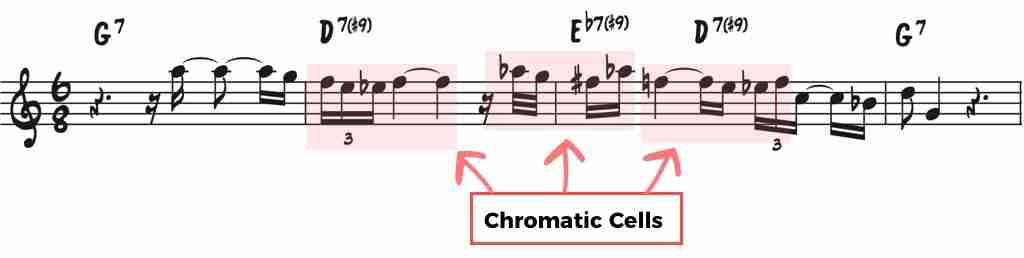

In Coltrane’s solo on All Blues, he takes some of his basic bebop dominant language and applies it in a completely new way.

He uses familiar little chromatic cells from a bebop scale but takes them out of there original key, placing them into a new harmonic situation, giving a completely new meaning to the notes he’s playing…

This is ridiculously powerful – tiny familiar bebop cells that can quickly and accurately allow him to glide through the chord changes.

You would think that everyone would take their current jazz language and use it in new situations like this, but it’s not that easy…

To even attempt to do this, you need to be able to think and visualize language fast with zero effort. With visualization practice you’ll be able to take your basic dominant language and move it into new harmonic places like this because you’ll be able to think in real-time…

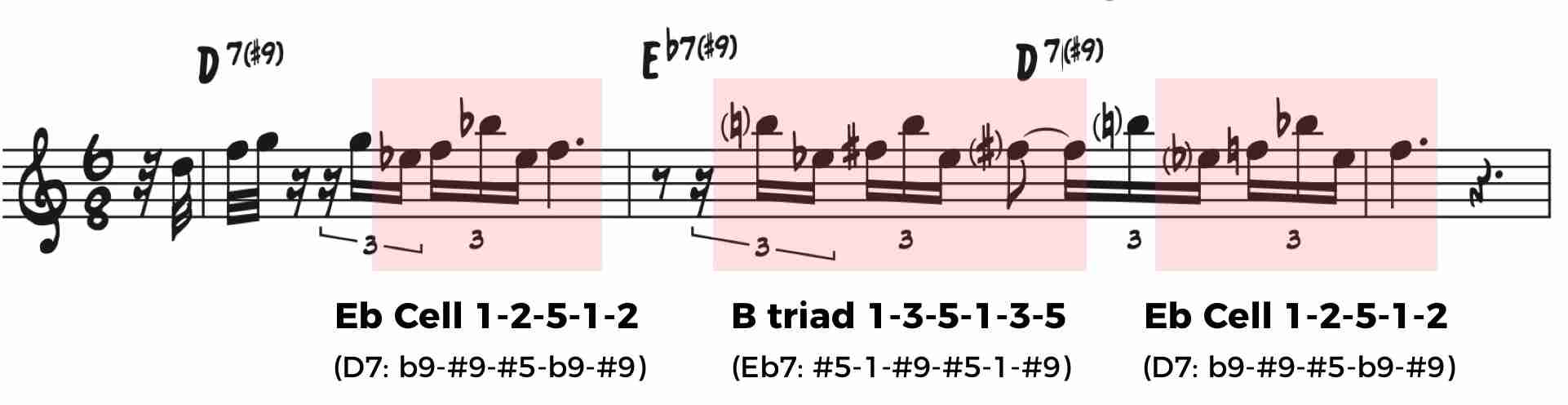

Moving back to Coltrane techniques, he doesn’t stop there…

Later he uses cells again, but this time he bases the cell upon the b9 (Eb on D7), using a note-grouping of 1-2-5-1-2 twice in this phrase. And, like Cannonball, he also makes use of the #5 triad over Eb7.

You can always depend on Trane to be pushing the envelope and come up with something that sounds new. Digging into his playing, you’ll uncover little gems of melodic information that can completely transform your playing.

Mastering All Blues & Other Musical Problems

So now do you have a better idea of how to play over All Blues? You certainly should!

At this point, hopefully you’ve gone from barely understanding the two measures that give everyone trouble to…

- Being able to clearly hear the altered dominant chords

- Knowing how to play the altered chords at the piano

- Having a better understanding of how to solo over these chords

But now it’s your turn…

Use the same process we went through today to identify and tackle any musical problems you might be having or encounter in the future.

It’s this process that’s so important to take into your practice room – it will allow you to learn anything you want to, grow in any direction you desire, and improve as a jazz musician faster than ever before.

Remember, once you’ve identified a music problem you want to solve, isolate the area…listen and transcribe the rhythm section to focus on what’s happening harmonically.

Figure out some basic piano chord voicings and practice playing them. Get the sounds of the chords resonating in your ear!! Transform your mental chord symbol and scale knowledge into something you truly hear.

Then, figure out how your favorite jazz musicians are dealing with the musical problems you wish to solve. Transcribe them and break down their melodic techniques. Put them into musical concepts you understand and practice them.

And have fun doing all this! It’s truly an adventure of challenge and discovery when approached in this systematic, yet playful manner.