Chord function is a confusing topic that is intricately tied to other just as confusing topics like voice leading, harmonic tension and resolution, intervallic content, chord voicings, chord families and more! Today we’ll unravel the slew of questions that arise from exploring chord function. Questions like, how do you build chords within a key? Why do specific chords have a natural tendency to push toward other chords? What makes harmonic tension and resolution?

Whether you’re just learning how to improvise or if you’ve been playing jazz for a long time, chord function can still be one of those things that doesn’t quite make sense because it’s a very deep topic.

Understanding the how and why behind chord function will allow you to learn and conceptualize jazz standards more easily, transcribe jazz solos more effectively, and compose more creatively.

It’s a must no matter what instrument you play or what styles of music you’re involved in. But, take your time with it. Although the idea of chord function is simple in theory, as you’ll soon see, there’s a lot to it. Take your time…

How to Define Chord function in a Major Key

While chord function is a tricky concept to grasp, working through an example one step at a time makes it easily understood and teaches you the process behind defining chord function.

Make sure to focus on the process used in the example and not just the specifics used in the example. Then, you’ll be able to apply the same process to more complex scenarios.

Here’s an overview of the 3 steps to define chord function within a key:

- Choose a key center and quality, then write out the scale from the tonic of the key that you will use to build chords from. It’s most common for the quality to be either major or minor, and the key to be one of the 12 keys. Technically though, you could harmonize other scales besides major or minor, and in some jazz compositions and in 20th Century Classical Music, composers actually do, so it’s nice to be aware of this.

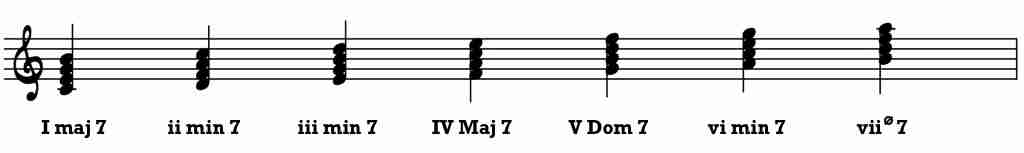

- Build seventh chords from each note of the scale by stacking diatonic 3rds. Diatonic means “within the scale”. And remember, this process of building seventh chords is called “harmonizing” the scale.

- Label each chord based upon the resulting chord quality and numbered position it occupies within the key. This is what it means to define “chord function” within a key.

So, let’s figure out how chords function within the key of C major:

- Choose the key of the tonic (C), the quality (major), and the scale to harmonize (C major scale)

- Build seventh chords from each note of a C major scale using diatonic thirds (Intervals of a 3rd within the C major scale)

- Label each chord by quality and numbered position. Typically, Roman numerals are used to indicate position of a chord within a key and capitalized numerals represent “major,’” while lower case represents minor. We’ve written the qualities out for sake of clarity.

Pretty simply right?

To emphasize again, it’s important to understand this process and not just the final result. If you really have a clear understanding of the process behind defining a key center and creating chords that function within it, you can easily apply the same process to other keys and scales.

This process in major is where ii V I progressions and many of our essential chord progressions come from. These chord progressions arise from this process because when harmonizing a scale, the resulting chords will have varying levels of harmonic tension in relation to the tonic chord that our ears can hear based upon one single important concept that people rarely talk about: intervallic content.

Intervallic Content and Chord Resolution

Intervallic content is just a fancy way of saying, the intervals contained within something. The something could be a chord, a scale, a melody…

But the point is the same…

The intervals contained within a musical structure create the aural characteristics that we hear.

Each one of the chords that we built within C major contain different intervalic content which results in a varying amount of aural stability or instability within each chord structure.

The more unstable the chord the more it “wants” to resolve to another chord, whereas the more stable a chord is, the more our ear is just fine with sitting on it all day.

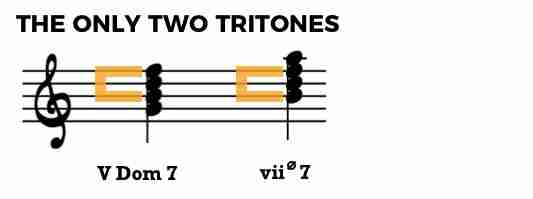

One of the most unstable intervals within a diatonic context is the tritone. Chords built from harmonizing the major scale that contain the tritone interval have a tendency to want to be resolved. There are only two chords that we built that contain the interval of a tritone:

On the V7 dominant, the tritone interval occurs between the 3rd and 7th, and on the Vii half diminished, the tritone interval occurs between the root and the 5th of the chord.

These are the only chords from harmonizing a major scale that contain a tritone because all of other chords are either major or minor 7 chords. Major and minor 7 chords do not contain a tritone interval between any of their chord tones, so it makes sense that none of the other chords contain it.

The interval of a tritone in the context of a major key center creates tension that our ear picks up on and we want to hear it resolved to another chord. The specific way the tension is set up and resolved comes from the idea of “voice leading” which we’ll explore more later.

So if you’ve ever wondered why a dominant chord or a half diminished chord just feels like it wants to move, that’s why.

Things don’t just sound a certain way…they sound a certain way because of the intervallic content within the structure.

The details of how chords function in a major key

Mastering chord function within a major key is simple if you study the little details and ingrain them into your brain in a logical way.

Make sure you observe these CRUCIAL details we’re about to talk about that many people never see or hear.

To discover these details, can you tell me the answers to the following 5 questions WITHOUT looking at any of the diagrams in this lesson or a piano?

- What chord qualities of seventh chords are found in a major key?

- How many major 7 chords are there in a major key and which chords are they in terms of chord function?

- How many minor 7 chords are there in a major key and which chords are they in terms of chord function?

- How many dominant 7 chords are there in a major key and which chords are they in terms of chord function?

- How many half diminished 7 chords are there in a major key and which chords are they in terms of chord function?

The answers to these questions are things you want to know right away. Things that you never have to think about again. You should not have to look at a diagram, the piano, or even pause to know the answers.

Study these facts and commit them to memory.

Internalizing them will help you understand chords, chord progressions, and chord function within a major key much better. Go through and visualize them to get them solid.

Here are the answers to the questions from above:

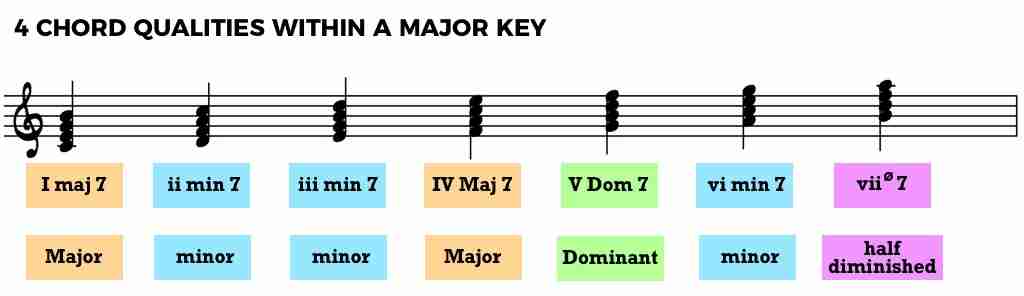

- There are only 4 qualities of seventh chords found in a major key:

- Major 7

- Minor 7

- Dominant 7

- Half diminished 7 (aka Minor 7 b5)

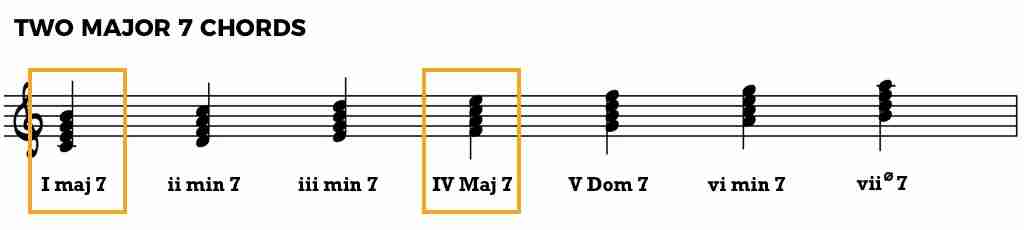

- There are 2 major 7 chords in a major key

- I Major 7

- IV Major 7

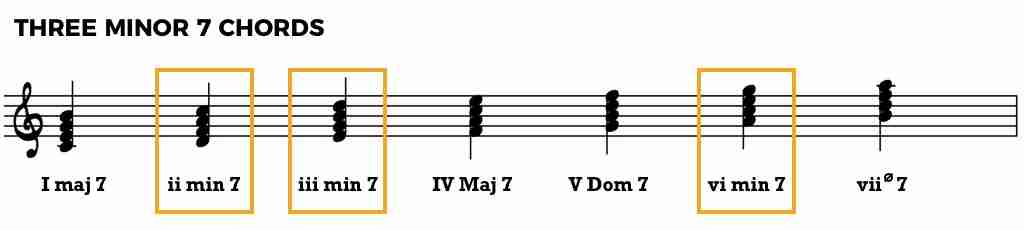

- There are 3 minor 7 chords in a major key

- ii minor 7

- iii minor 7

- vi minor 7

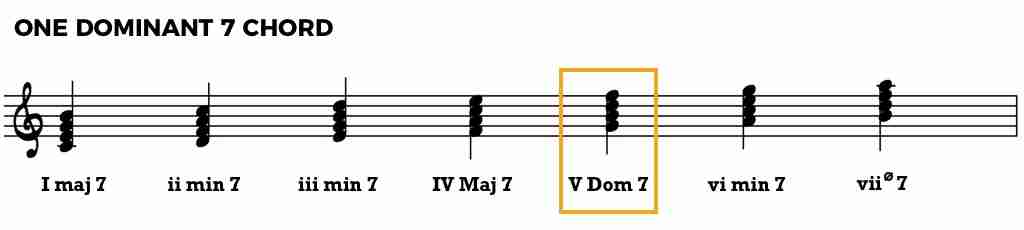

- There is only 1 dominant 7 chord in each major key

- V7

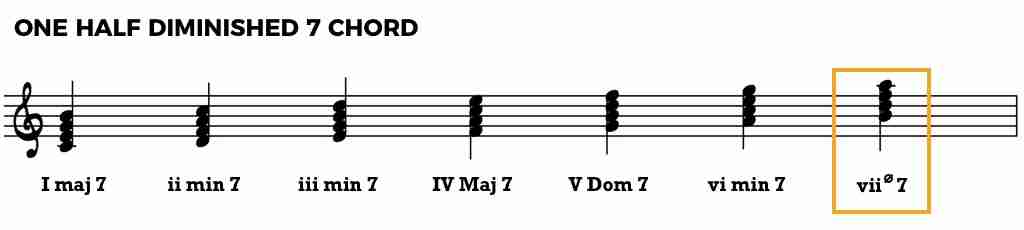

- There is only 1 half diminished 7 chord in each major key:

- Vii half diminished 7

Before you move on, look over these answers again and really get them in your head. They’re very obvious when you’re looking at a diagram or the piano, but you need them in your mind to make the information useful…

Understanding Chord Families: Tonic, Sub Dominant, and Dominant

I’m going to be real with you right now…I absolutely hated music theory in school…

Yes, I was extremely immature (understatement of a lifetime) and still am to some degree, but the way that music theory was isolated from everything else and explained made it difficult to see its relevance, and it is relevant, both as a performer and a composer.

The Tonal Harmony book, the examples used to explain the concepts, the lack of connecting theory to ear training, composing, and improvising. Just the mere idea of music theory can take what should be very useful tools and turn them into something no real player could ever use.

In fact, I urge you to reframe how you think about music theory. No longer think of it as disconnected rules that govern how music works. But instead, think of each concept as a tool to better hear, play, and compose with, connected to the way you hear and improvise…tools you can choose to use, not use, or to change or extend in your own way…

There’s so much from music theory that can make you a better musician. But, you have to understand the concepts in a way that puts them into contexts that you would actually use them in without drowning in the sea of the theoretical.

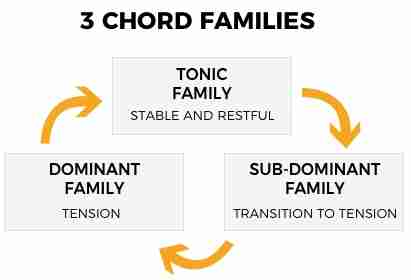

For example, let’s take our seven chords that result from harmonizing the major scale and split them into the 3 chord “families” that music theory talks about, but put the whole idea into a familiar context. To begin, here are the 3 chord families:

- The Tonic Family

- The Sub-dominant Family

- The Dominant Family

The names of these chord families give you a clue to exactly what types of chords should be in each family.

Let’s take a look at which chords are in which family and why…

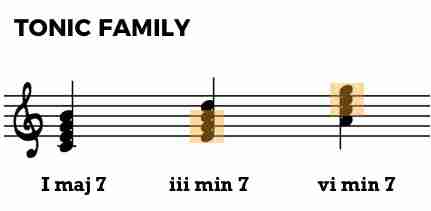

The Tonic Family

The tonic family describes the chords within the key that have a stable, tonic sound, hence the name “Tonic Family”. To create this stable sound, the chord structure of the tonic chord uses specific intervallic content and specific chord tones within the key center.

So, naturally, chords within this Tonic Family share similar intervalic content and chord tones to that of the tonic chord.

Knowing this, if you had to guess what other chords besides the tonic that would be in the Tonic Family, what would you guess? In other words, what other chords from our seven chords within a major key share similar interval content and chord tones to that of the tonic chord?

See how both the iii minor 7 and the vi minor 7 chords share three chord tones in common with the tonic chord?

As you can see, the Tonic Family consists of the tonic, the iii minor 7, and Vi minor 7 chords.

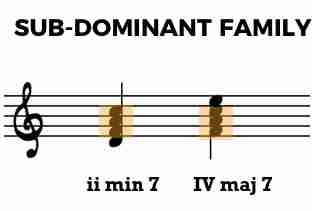

The Sub-Dominant Family

The Sub-dominant family describes chords that precede chords in the Dominant Family, or chords that move away from the tonic and typically transition to chords with tension.

Can you think of what primary chord in jazz might be in the Sub-dominant Family? Here’s a hint: what’s the most popular jazz chord progression that we’re always talking about?

The progression we’re talking about is the ever-so-present, ii V7 I chord progression. It’s everywhere. And what chord in the ii V I precedes the dominant chord?

The ii minor 7 chord, obviously.

Now, what other chord overlaps with the ii minor 7 chord and precedes the V7 chord in most pop music progressions, although most of the time without the major 7?

The IV major 7.

And the IV is even called the subdominant chord for a few reasons. First it’s the same distance below the Tonic (C down to F, a perfect 5th) as the Dominant is above the Tonic (C up to G, a perfect 5th). It’s also directly “under” the Dominant (IV is right under V) and “sub” can be thought of as “under.”

Now it should make sense to you why the I IV V progression used everywhere in pop music is very similar to the ii V7 I used everywhere in jazz.

Next we’ll take a look at the Dominant Family.

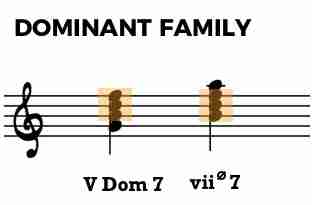

The Dominant Family

Within the Dominant Family, like the Tonic Family, it’s pretty easy to guess one of the chords that you’d expect to be in the family.

Just as you’d expect the tonic chord to be in the Tonic Family, you’d expect the V7 dominant chord to be in the Dominant Family, which it is.

But what other chord do you think is in the Dominant family? Use the same thinking as before. What chord from the other six chords within a major key shares similar intervallic content and chord tones as the V7?

Notice the overlap between the dominant and half diminished chord and how both contain a tritone.

These 2 chords are the only chords within a major key that contain a tritone interval.

The Importance of Chord Families

Knowing these chord families and their names can help you understand quite a few things…

First, chord families help you understand how chords tend to move away from stable Tonic Family chords to Sub-dominant Family chords, followed by Dominant Family chords, and back to Tonic family chords.

These are just tendencies of how chords within a major key move…

Of course you’ll find chords in progressions that don’t obey these movement patterns, but by understanding how chords use this idea of chord families, you’ll get an idea of how composers move between tension and resolution, even if they’re not using these precise methods.

Another important point you can learn from chord families is how diatonic chords can be substituted for one another. It’s quite common that the iii minor 7 or vi minor 7 chord is substituted for the I Major 7 chord.

And now you know why…

Because any chord within the same chord family can be substituted for another chord within that family.

Composers do this and piano players, or other comping instruments, do this in real-time, so it’s necessary to be aware of it.

Now that you have an idea of how chord families work, the next thing to understand related to chord function, is that moving from chord to chord, there’s natural “voice leading” that takes place from one chord to the next…

Chord function and voice leading

I’m sure you’ve heard people say, “The 3rd and the 7th are the most important notes of a chord,” and they’re right when it comes to harmony.

Although, most of the time, they’re referring to melody, which actually depends not just on the 3rd and 7th, although they’re incredibly important, but your knowledge of ALL chord tones (and non-chord tones) in a chord and how they relate to the underlying chord voicing and to each other.

But in terms of harmony, the 3rd and 7th not only dictate whether the chord is major, dominant, or minor, they also define the primary voice leading of chord tones from one chord to the next.

Chord function is closely related to voice leading because in general, chords function in a way that create smooth voice leading, and by “smooth” we mean the chord tones that create the intervallic content that we hear as tension (or “voices” if you think of each of the 4 notes in a chord as a voice: soprano, alto, tenor, and bass) tend to transition from one chord to the next using minimum motion, usually half-steps or whole steps.

Think about it. If chords functioned in a way that couldn’t use smooth voice leading that resolved tension by small movements like half-step or whole-step, you’d have these big leaps from one chord to the next, and the result wouldn’t sound logical, smooth, or what we hear as beautiful.

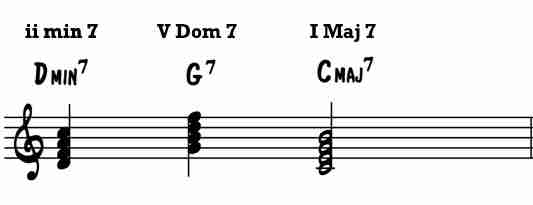

For an example of smooth voice leading within a common chord progression, let’s look at the voice leading of the 3rd and 7th within a ii V I.

Here are the root position chords as in our chord function diagram from earlier.

But, in jazz, no one would ever play the chords this way because jumping from chord to chord like that does not only sound bad, it doesn’t aurally describe the voice leading from one chord tone in the first chord, to another chord tone in the next chord.

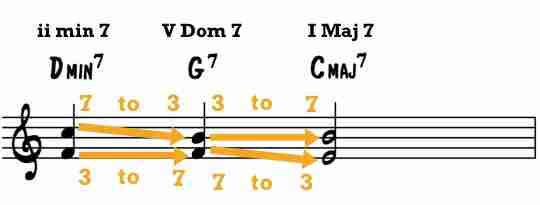

To see and hear how the voices of one chord progress to the next, simplify the chords by focusing only on the 3rds and 7ths:

See how the 7th of the D minor chord (C) moves down a half step to the 3rd of G7 (B) while the 3rd of D minor (F) carries over and becomes the 7th of G7?

And then the 7th of G7 moves down by half-step to the 3rd of C major (E), while the 3rd of G7 carries over to become the 7th of C major (B).

The way these chord tones move also define a specific interval over each chord. What begins as a perfect 5th on D minor, becomes a tritone on G7, and then transforms into a perfect 5th again on C major.

Notice how just by following our guidelines of moving from a Sub-dominant Family chord to a Dominant Family chord and then to a Tonic Family chord smoothly sets up the tension of the V7 chord by half-step, and then smoothly resolves the tritone tension by half-step?

This smooth voice leading is always present even in other progressions. With all the tunes you’re working on, sit at the piano and play through the tune with 2 or 3-note piano voicings, and pay careful attention to the voice leading from one chord tone to the next.

Chord Function and The composer’s mindset of “What If…”

The great composers of jazz standards were masters of jazz chords and chord function. In general, they formally studied composition and were well aware of how to utilize the tools of music theory.

But the “rules” of music theory never limited these composers because they were always thinking to themselves these 2 magic little words…

WHAT IF…

What if I resolved the V7 chord to this chord instead? What if I substituted this chord for this chord? What if I went here instead of the obvious place?

Always thinking “what if” is the key to the composer’s mindset and getting beyond the standard guidelines of jazz theory, because that’s actually what they are. GUIDELINES.

Nothing says you have to obey the ideas from music theory. They’re not the Laws of Physics. They’re simply tools to help you understand, play, and compose music in a more organized and approachable way.

Let’s take the first 8 bars of All The Things You Are to get an idea of how music theory might guide us toward composing these original chord changes by using the “What if” mindset…

You’re probably familiar with these chords and they probably make sense to you, but have you ever thought about how the composer came up with these chords, or why each chord is there in the chord progression?

It’s this curious attitude that will give you a deep understanding of the tune.

Ok, so how would you come up with the idea of starting a tune on the Vi minor chord, or somehow transitioning to the key center a major 3rd away? Music theory can sometimes be difficult or confusing to actually use or apply in real situations.

It’s like, okay, I just learned how chords function in a major key, but how come in the chord progressions going on in real tunes, chords don’t always function like that?

The thing is, if composers strictly stuck with music theory to create everything they came up with, things would be very predictable, and that’s not what they want. They want some predictability, mixed with some sense of originality, uniqueness, and surprise.

What great composers do is use theory to set up the predictability, and then PURPOSELY go AGAINST where you’d expect the chord changes to go.

People are fond of saying learn the rules and then you can break the rules, but it’s way more specific than that. First off, they’re not rules, they’re tools. And second off, it’s how you deliberately choose to use, change, modify, and extend these so-called rules that matters.

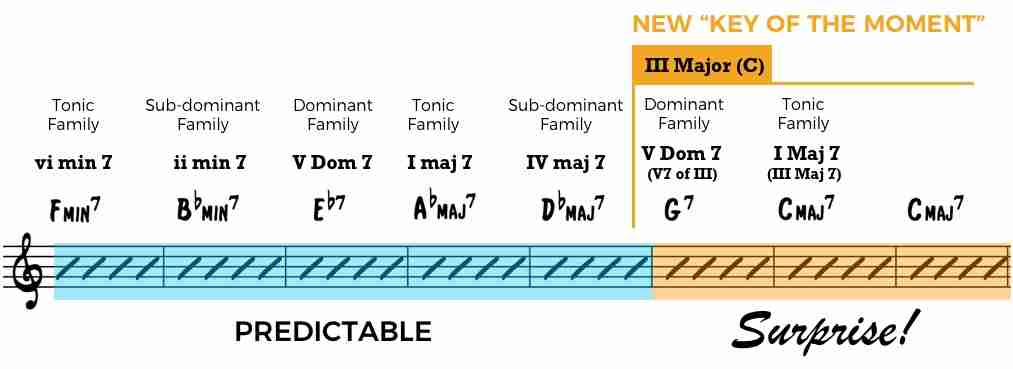

Let’s look at how this idea of using theory both predictably and unpredictably in All The Things You Are creates a unique composition.

Chord Function and Originality in All the Things You Are

In the first 8 bars of All the Things You Are, the chords themselves are fairly straightforward, but when you put them together in a chord progression, it can seem like these chords are all over the place.

Using the idea of “What if…” you might come up with this progression by first thinking about, “What if I start from the Vi minor 7 chord, a Tonic Family chord, move predictably the way chords typically move, but after reaching the IV major chord, I somehow move to the III Major chord…”

These are the kinds of “What If” questions composers are toying with, and with this question you might come up with this:

Notice how even when pivoting to the III Major 7 chord via its V7 chord, the chord families still progress from Sub-dominant Family (IV major) to Dominant Family to Tonic Family?

It’s pretty interesting just to note that it’s the same underlying formula, but used to arrive at a new key center, or what I like to think of as a “key of the moment.”

And when using this “What if” mindset and experimenting, as the composer, if it sounds cool to me, I might go with it.

By trying things out and experimenting using the “What if” mode of thought combined with your knowledge of chord function, you can discover unique progressions that sound interesting or go behind the scenes of how a composer of a tune you’re working on might be thinking. And if you can get into the composer’s head, your understanding of a jazz standard will sky rocket!

With any jazz standard that you want to learn, aim to get a step beyond analysis. Think about how the composer might have come up with these chords.

In doing so, you’ll improve your composition skills, and you’ll discover what makes a specific tune special in its own way, making it easier to learn, recall, and improvise over.

Things to watch out for with chord function

Chord function is a great tool to have at your disposal, but like any music theory tool, there are things to watch out for that can hurt your musicianship if you’re not careful. Here are some things to watch out for…

Chord function does NOT describe all the possibilities of chords within a progression

Remember, these are guidelines and tools, not rules. Chord function in a major key describes how we tend to hear the tension and resolution of the chord structures built on a major scale.

This doesn’t mean we have to stick to the way chords tend to move. We’re free to compose or think about chords moving in any way, the sound being the most important. As you learn more and more tunes, you’ll realize sometimes chords go from Tonic Family chords straight to Dominant, or sometimes they go from Dominant Family chords to Sub-Dominant.

There’s no one correct way, but knowledge of the guidelines helps you hear and understand the many possible variations.

Not all chords in a jazz chord progression have to serve a specific function within a key

Being human, we want everything to fit into our nice little theoretical box, but sometimes when working on tricky tunes, like Wayne Shorter tunes for instance, it’s difficult to hear or to determine what the composer was actually thinking in terms of chord function. Or, there be multiple ways to hear or think through the chord functions…

There’s nothing wrong with this and the way we hear or think through chords can vary greatly from person to person.

Don’t get caught up in being “correct.”

Your goal is to better hear, conceptualize, remember, and understand chord progressions so they are easy to both think about and play over. Anything that helps YOU do that is beneficial.

Basic chord function does not encapsulate all of music theory

Music theory is a deep subject. What we went over today just touches on the basics of how chords function in a major key. With use of other principles like borrowed chords or tritone substitution, basic concepts can become quite advanced very quickly.

Just because it’s not explained by chord function doesn’t mean it can’t be explained some other way.

But, on the other side of the coin, don’t get obsessed with needing a complete theoretical explanation for everything.

Some things just sound great, and you can always use tools like intervallic content and voice leading to figure out why they sound great to you, even if you can’t determine an exact chord function.

Do NOT use chord function to memorize chords from a lead sheet without learning the SOUNDS of each chord and the total progression

You can “know” the chords to a jazz standard or a common progression like a ii V I, but do you actually know how they sound? Have you spent time playing basic piano voicings to get the sounds in your ear?

This step is one of the most important steps in grasping chord function. It means nothing if you can’t hear it. Put in the time and connect with each chord and how each chord progresses. Only then will chord function mean something meaningful to you.

Do NOT use chord function to group multiple chords into one key so you can play ONE scale on all of them without knowing what’s happening harmonically

This right here is one the BIGGEST mistakes in jazz education. I see it all the time and grew up with it. Instead of helping students understand how chords progress and why by using concepts like chord function, voice leading, and intervallic content, teachers will instruct students to play a single scale over several chords because they all “come from the same key.”

Just because there are seven different chords built by harmonizing the major scale does not mean that you simply play the tonic major scale over all of them.

Each chord is a specific sound with many harmonic and melodic possibilities. Use everything we’ve talked about today to develop an understanding of each chord, how it relates and progresses to other chords within the key, and how tension and resolution are handled through voice leading and intervallic content.

Remember, chord function in the context of a chord progression describes a whole lot more than what key a chord is in.

It describes relationships and movement between chords, as well as the amount of tension within each chord and where that tension goes.

Why a clear understanding of chord function is essential

So now that you have a solid grasp on the details of chord function and how it relates to intervallic content, voice leading, chord families, and the composer’s mindset, let’s recap why chord function is such a useful concept and why it’s worth your time.

Chord function describes purpose

One of the primary things people forget about chords within a key center is that each chord has a purpose.

If you truly understand how the chord is functioning, you will understand the purpose of the chord and why the composer chose to use that specific chord at that specific place in the tune.

In jazz standards, chords are not random. Each chord was selected by the composer to move somewhere or to resolve from somewhere.

Chord function helps you memorize jazz standards and play them in all keys

Learning chords by chord name is only useful in one key, but knowing how each chord functions within the key and how it moves to other “keys of the moment” will allow you to play the tune in all keys.

If you develop a working relationship with the concept of chord function, your ability to learn jazz standards fast and recall the progressions with ease will progress quickly.

Chord function gives you mental and aural anticipation

This skill is extremely useful. When you’re transcribing or listening to a tune, you want to have a mental and aural idea of where the chords should go strictly based upon how chords tend to function.

This knowledge allows you to anticipate where chords usually go, and if they don’t, to have a frame of reference to compare to.

Chord function helps you compose

By combining your knowledge of chord function with the composer’s mindset of “What If,” you can set up predictability and surprise.

You don’t need to be limited by chord function. Instead, allow it to inspire ideas and get the ball rolling. Then, deliberately go against, modify, or change how typical chord function might go.

Chord function helps you with chord substitution

By classifying the diatonic chords into the 3 chord families, you can see how closely related certain chords are. Chords that share almost the same intervallic content and chord tones can usually be substituted for one another.

These substitutions explain why iii and vi minor 7 are commonly substituted (and sound like) the tonic I major 7 chord.

Always be aware of these substitutions, that they can occur in the jazz standards you’re learning, used as a tool of composition, or employed by the chording instrument in your band.

To sum up, a deep understanding and knowledge of chord function helps you:

- Understand the purpose of each chord and why the composer or performer decided to use each chord where they did

- More easily remember chord changes

- Anticipate where chords might go when listening or transcribing

- Compose more effectively

- Understand chord substituions

And that’s really just the beginning because in this lesson we’ve only touched on harmonizing the major scale. In future lessons will go through the process and details of harmonizing a minor scale, using borrowed chords, and a whole lot more!

Chord function, as you can tell from today’s lesson, is not an easy concept to grasp. What starts out as a simple way to build and define chords within a key, quickly bubbles out into something that overlaps with many of the fundamental concepts at the very heart of music.

Your understanding of chord function will develop as you acquire more practical music theory and hear how it’s operating within the jazz standards you’re working on.

Always ask yourself if there are any spots in a tune where you technically know the chords but you don’t know how the chords are functioning or why the composer or performer might have used each of these chords.

Pull it apart. Use intervallic content, voice leading, chord families, and tension and resolution to better understand how each chord functions. With these tools at your disposal, you’re much better equipped to learn tunes faster, understand chord progressions on a deeper level, and compose the music you’ve always wanted to.

Just remember, don’t drown in the theory…not everything in music or life needs to always make sense. Most importantly, focus on sound and creating what you consider beautiful music!