Bebop “heads,” what jazz players sometimes call the melody of a tune, tend to be some of the trickiest and most technically demanding strings of notes you’re likely to encounter. Much busier than classic jazz standards, these intricate melodies are generally more difficult to learn, understand, and commit to memory.

So what do you do when you inevitably come across one of these bebop tunes?

Sure you can play it over and over until you’re blue in the face, and that will certainly help, but beyond any brute force approaches, the key is to break down all of the concepts & techniques within these bebop gems…

By understanding what the composer is doing, you’ll be able to add these tunes to your repertoire more easily and you’ll acquire powerful improvisational concepts that you can utilize in your solos.

You see, one aspect of this type of tune that makes them so valuable is that they’re often built upon the chord progressions of popular jazz standards, giving you a new pathway and perspective over a familiar harmonic vehicle.

In jazz we call these new melodies, contrafacts.

So if you’ve been struggling over a particular tune or just want a fresh take on the changes, what better way than to see and hear what a great composer made of them?

This is an invaluable process and it’s exactly what we’re going to show you how to do…

Today we’ll look at Tadd Dameron’s creation Hot House, which is written over the chord changes to Cole Porter’s What Is This Thing Called Love.

Here are just a few of the things you’re going to learn:

- How to use chromaticism in a more advanced way

- How to hear variations of altered V7 sounds that are likely new to you

- How to conceptualize pieces of a bebop melody from different angles

- How a bebop melody can give you a new way to think about chord changes

- How composers use certain dominant shapes within their melodies

And a whole lot more…

But before we go any further, take a listen below to masterful trumpeter Wynton Marsalis play over What Is This Called Love.

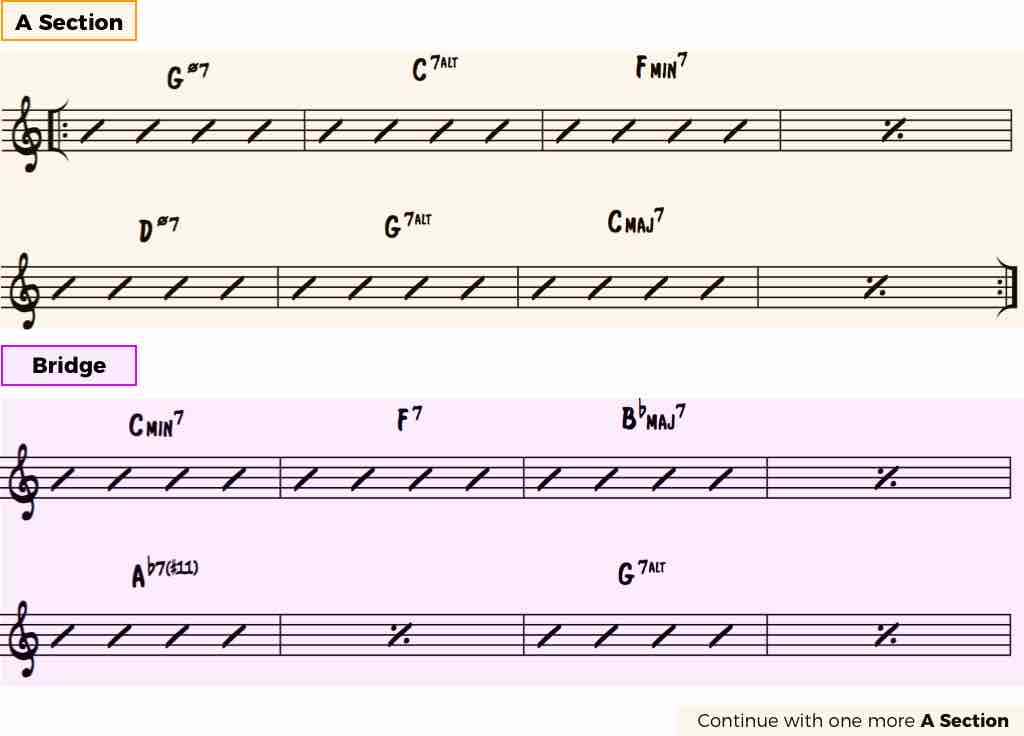

With an AABA form, these straight forward chord changes are ripe for a new melody…

So in 1945, the legendary composer Tadd Dameron did just that…he took these changes and created a new approach to how you might move through them.

He called this new creation Hot House and the bebop greats Charlie Parker and Dizzy Gillespie quickly adopted this new melody as one of their favorites. Have a listen…

Throughout their careers, they recorded the song numerous times, with slight variations and embellishments from take to take. (Note that we’ll use the recording above as our primary study because it’s the most clear)

We’ll go into a little of this variation later, but don’t get too hung up on the variations and embellishments in various recordings or charts.

Instead, try to grasp the larger picture of what the melody of Hot House teaches you about how to weave through the chord changes to What Is This Thing Called Love.

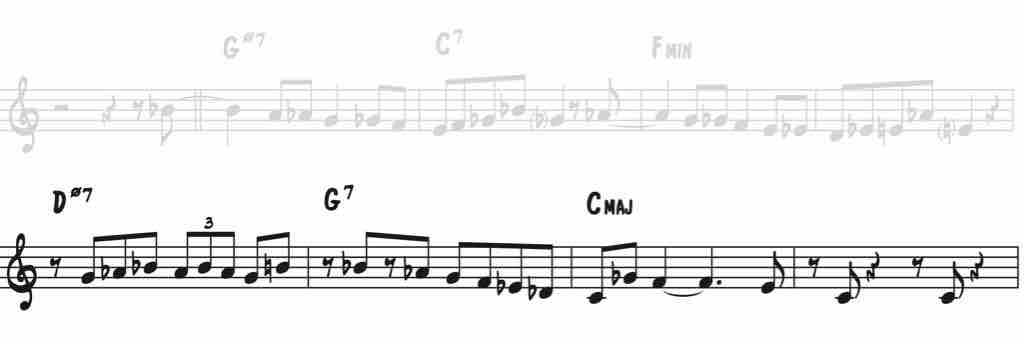

We’ll take it a section at a time, starting with the first A, which is packed full of useful bebop techniques.

Okay, let’s get started…

The First A Section of Hot House

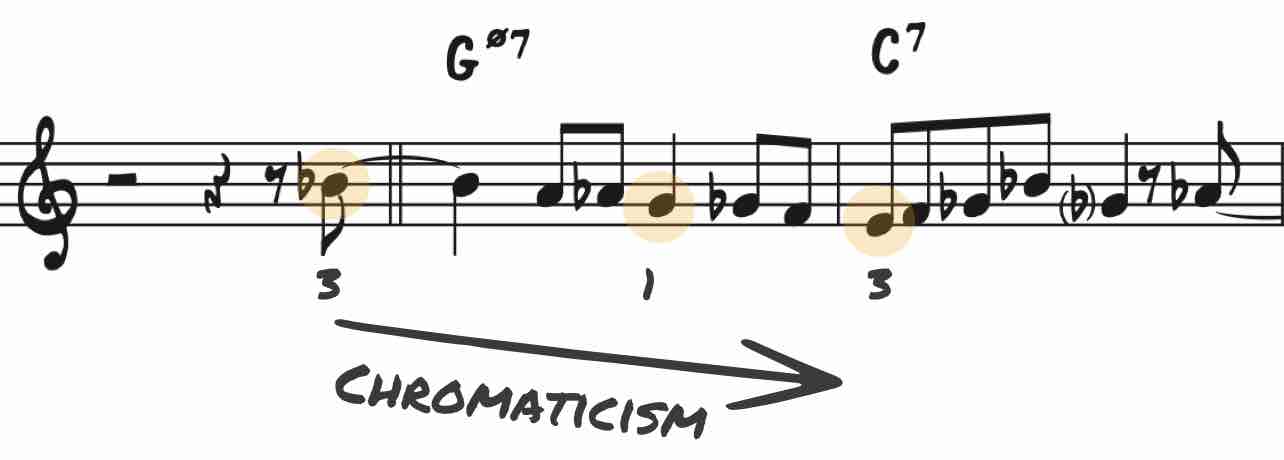

One of the most powerful improvising concepts that separates amateurs from professionals is their keen use of chromaticism.

Sure, most improvisers eventually discover Bebop Scales, which gives them an entry point into chromaticism, but beyond that, most improvisers fall short.

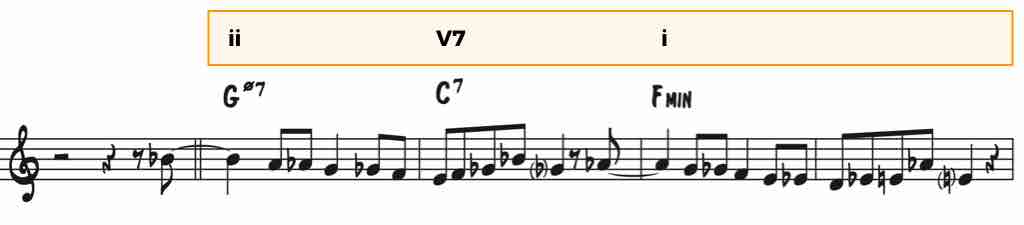

By studying the first 4 bars of Hot House, you can learn how to use chromaticism in a most interesting way.

So how does this work? How does this melody successfully use so much chromaticism and still communicate t?

The Power of Chromaticism

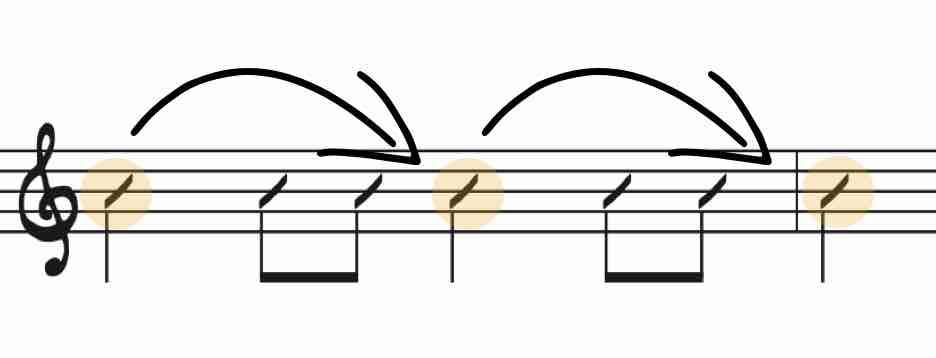

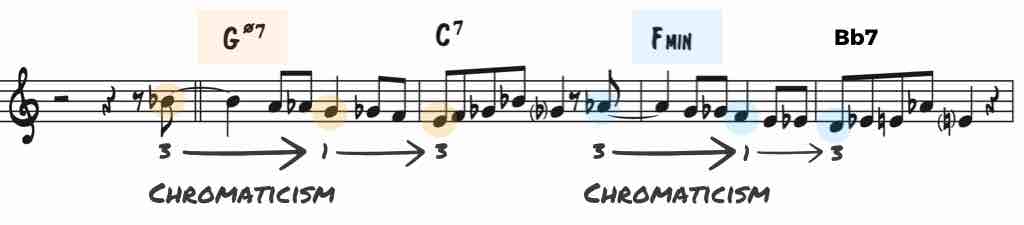

Well, when it comes to chromaticism, it’s all about how the pitches that are placed on downbeats align with the harmony.

In this case, Tadd begins by targeting the 3rds and roots of the chords.

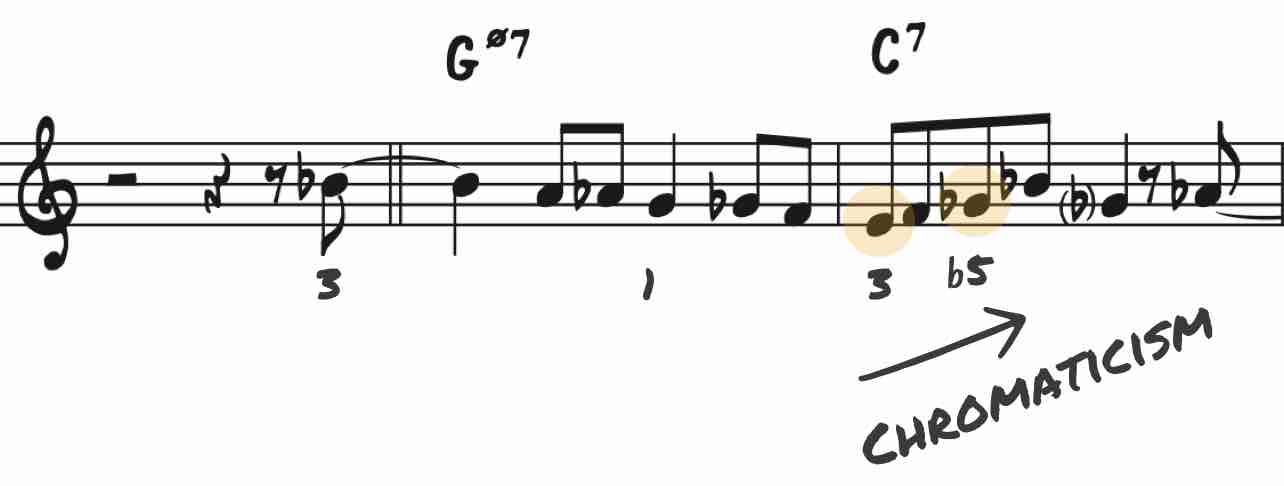

And then, changing direction, he targets the b5.

Now, if you really understand this phrase and break it down, there’s so much you can learn from this single piece of the melody.

First, notice the rhythm in the first bar…nothing in this phrase works without the rhythm.

It’s this specific rhythm that allows Tadd to lead into the chord-tones on the downbeats where he wants them, and it’s the rhythm that gives the line definition and form.

Try adding this rhythm to your rhythmic vocabulary – perhaps improvise a chorus on blues or rhythm changes using this rhythm as your main improvisational tool. You might surprise yourself how creative you can be with only a single rhythm.

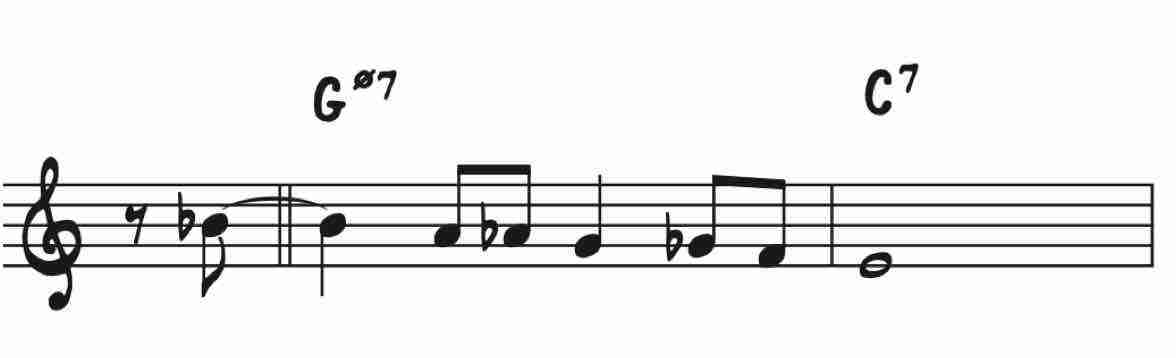

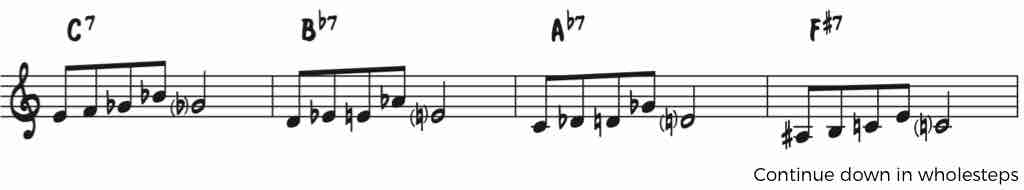

Next, using that rhythm, learn to walk down from the 3rd of the half diminished chord to to the root, and then continue to the 3rd of the dominant chord…

And to make it exactly like the melody, let’s add the eighth note anticipation on the and of 4 leading into beat 1…

This is a beautiful run that takes you chromatically through the whole first chord and perfectly pushes to the 3rd of the V7 chord.

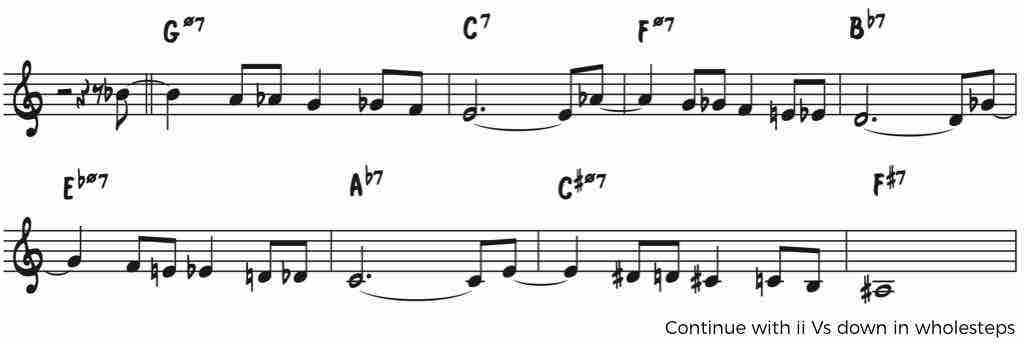

To master this elegant use of chromaticism, practice taking this phrase down in whole steps through all 12 keys (There are two groups of six keys to practice. For more info on how to practice like this, see this lesson).

But as you know, the chromaticism doesn’t stop there…

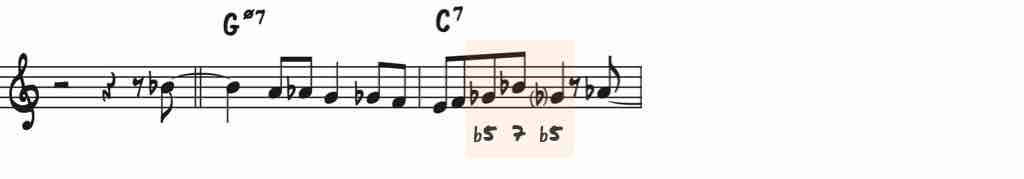

It then changes directions and moves up from the 3rd to the b5 with a quick jump up to the 7th of the chord and back down, which can be a little tricky to hear…

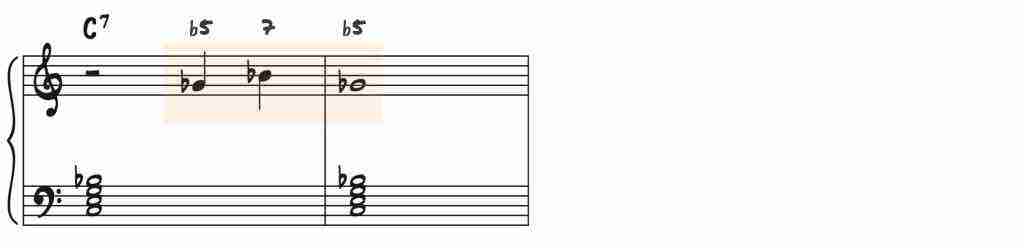

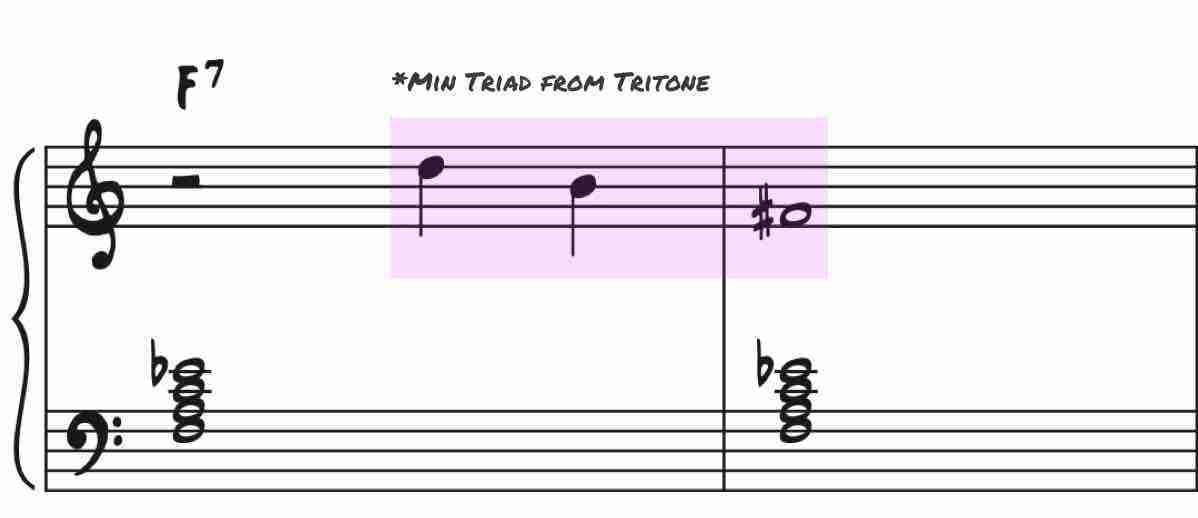

Learning to hear V7b5

The most difficult aspect of this piece of the line is the way it sounds and it’s because your ear is probably not that familiar with this particular combination of notes over a V7 chord: The b5 & 7th

So the first thing to do is to train your ear to hear this sound.

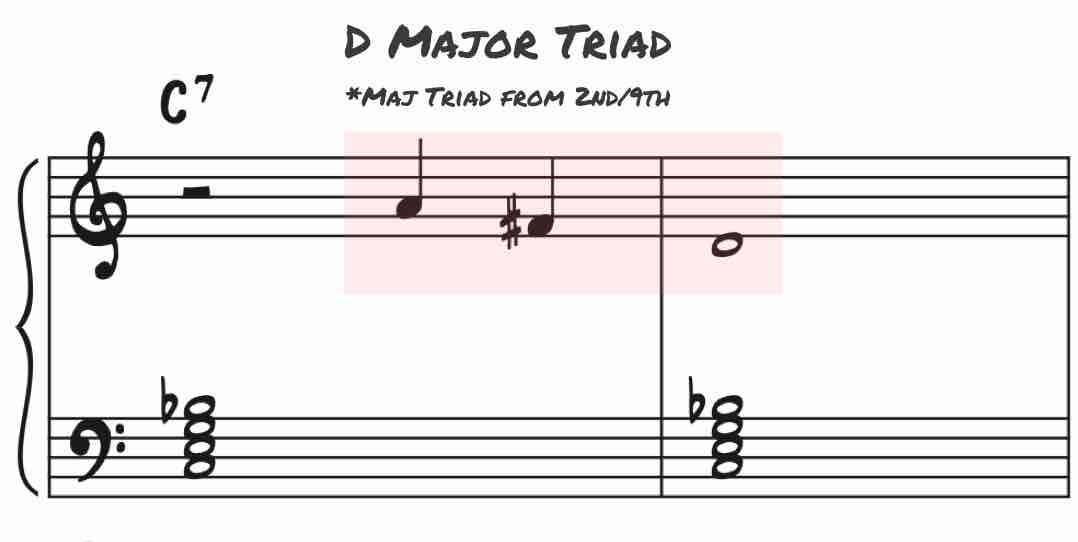

Sit at the piano, play a C dominant chord in the left hand and then alternate between playing the b5 & 7th of the chord in the right hand, letting the sound of the two notes over the chord sink into your ear.

Repeat this in a bunch of keys until your ear can easily hear these chord-tones in this context, and then, play the V7 bar in all keys down in whole steps…

So at this point, you should have the entire first phrase under your fingers and have a solid understanding of it.

However, it’s always useful to have multiple perspectives as to what’s going on, so next let’s take an alternate view on how you might interpret what’s going on over the V7 chord…

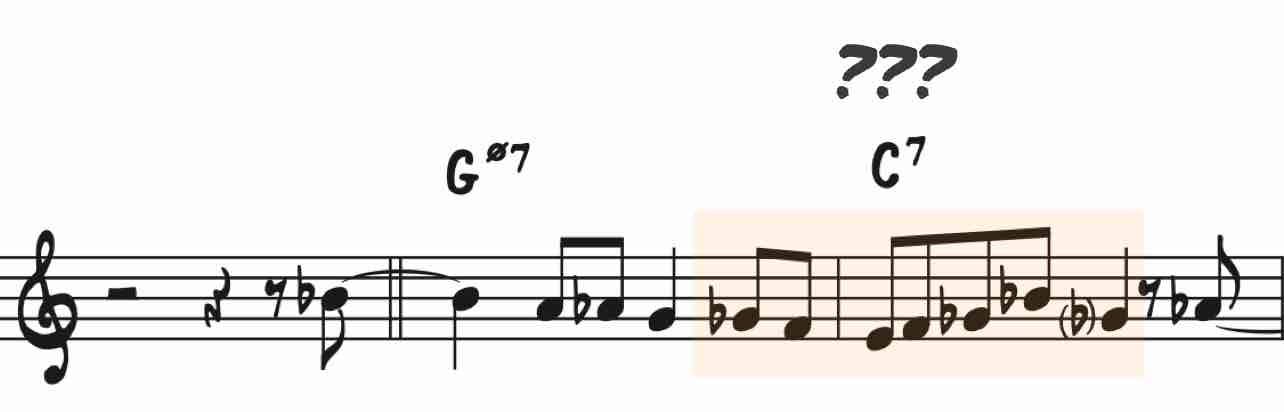

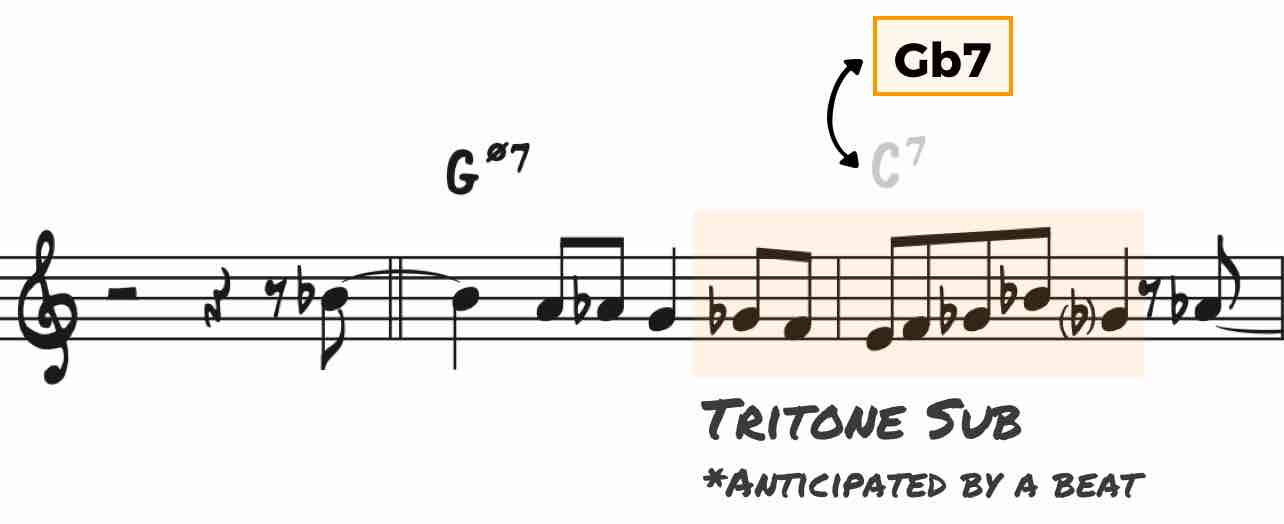

The not so obvious Tritone Sub

If you look at the phrase again, is there another chord that you might think of instead of C7 here?

If you look closely, you might realize that all the notes here are part of a Gb7 bebop scale fragment, which is the V7 chord that lies a tritone away from C7, a tritone substitution.

In this light, you might view the chords as G half diminished moving to Gb7 instead of C7.

This is a powerful alternate perspective that gives you new insight into the melody and harmony here.

Okay, now that we’ve gone super deep into the first two bars of the tune, let’s take a look at the next two bars and how they relate to the first.

How you think is everything

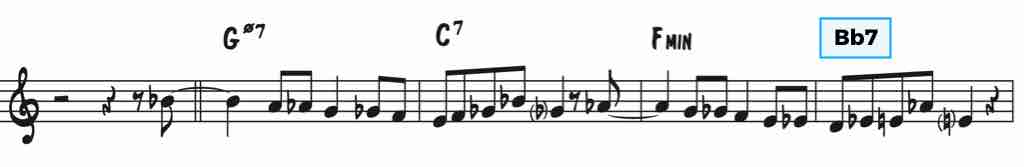

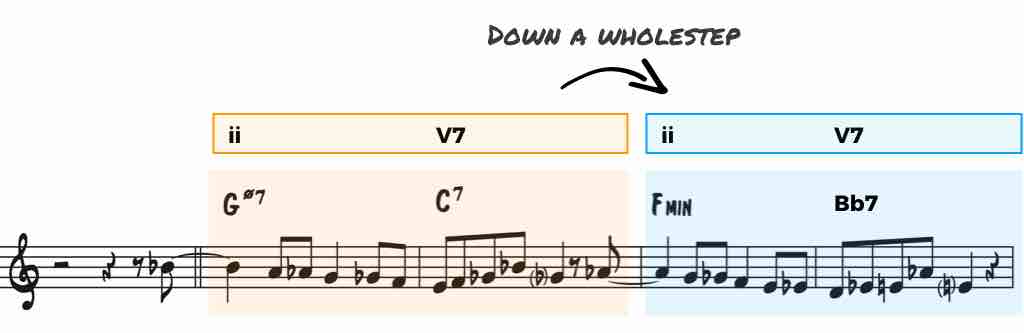

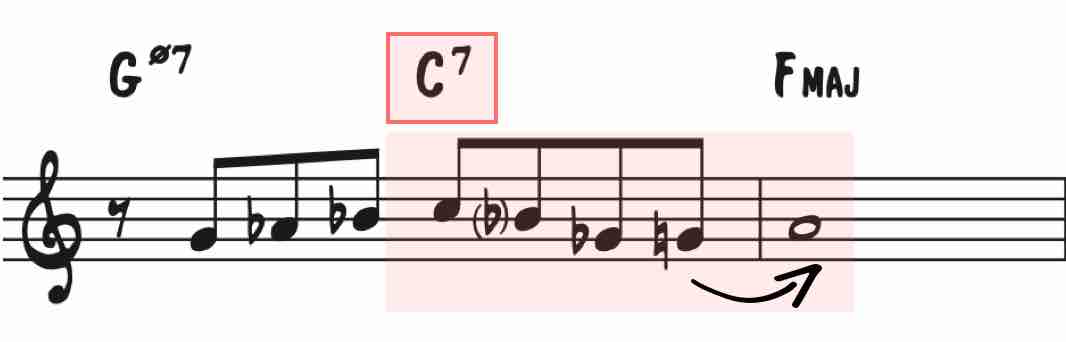

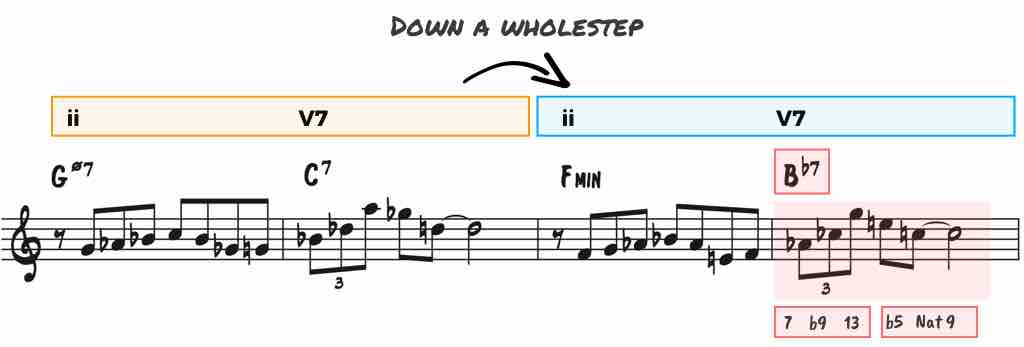

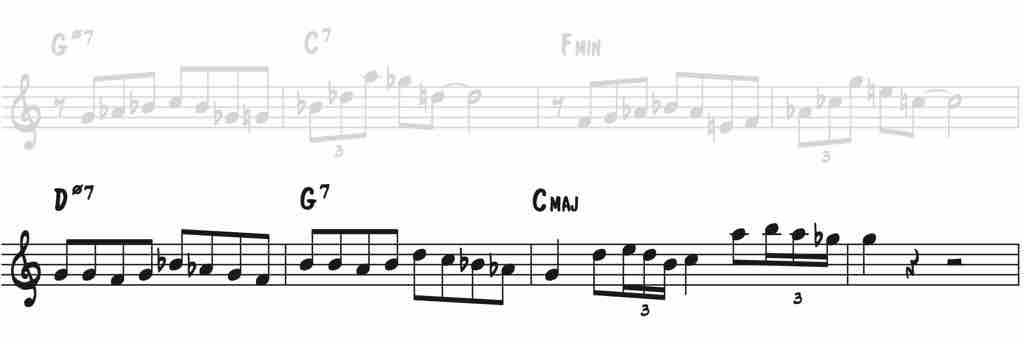

When you listen to the next two bars of Hot House, it’s probably obvious to you that they’re the same as the first, simply transposed to a new key…

But what might not be obvious is why it works, after all, the chords of What Is This Thing Called Love are a minor ii V resolving to i, so how could you use the same material over a ii V and a tonic minor chord?

So what tactic is Dameron using here that allows him to treat these second two bars like the first two?

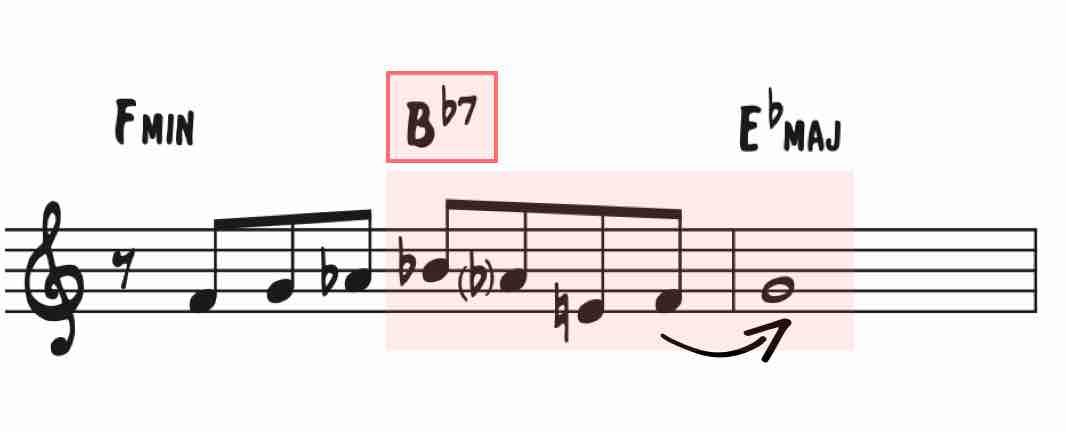

Well, instead of thinking of the entire bar as F minor, the tonic minor chord of the minor ii V, he instead treats the F minor as a ii chord within a ii V7, pairing it with Bb7.

This addition of Bb7 allows him to conceptualize the whole first four bars as two ii Vs that are resolving down by wholestep. (F- Bb7 lies a whole step below G-7b5 C7), hence he can use the exact same phrase in the appropriate key for both.

Make sure you understand this because it’s a subtle technique – rather than treating the chord as a i minor chord, he’s transforming it into a ii V.

And, it just so happens that the rhythm that we talked about before keeps the 3rd and the root on the downbeats for both half diminished chords and minor chords, so it allows the same phrase to fit over both of these chord qualities.

If that’s not powerful, I don’t know what is…and remember that we can view Bb7 as E7, the Tritone Sub as well…

Now remember, everything we’re talking about today is not just an explanation of Hot House…it’s much more that that…

These are specific tactics that a genius composer used to create a new pathway through What Is This Thing Called Love, giving you a completely new way to think about the changes.

So use everything you’re learning today to:

- Inspire a new approach over What Is This Thing Called Love,

- Internalize the melody of Hot House more easily

- Acquire bebop soloing tactics that you can use anywhere

Okay, let’s move onto the next four bars of the A section…

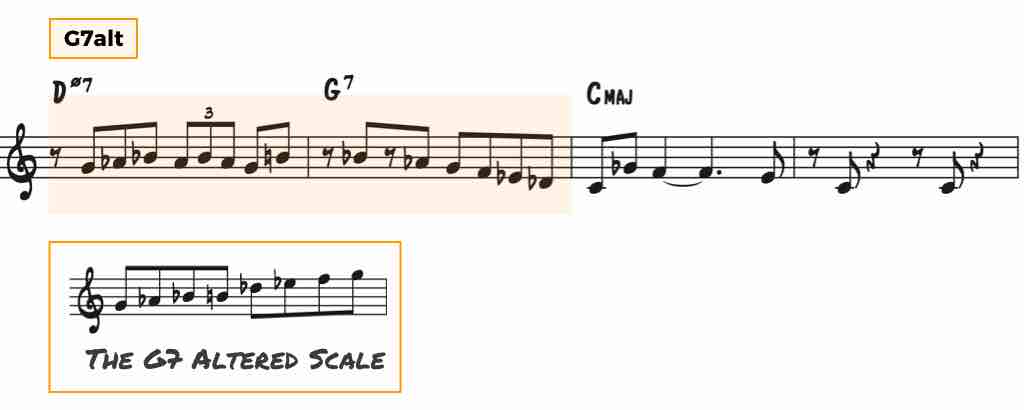

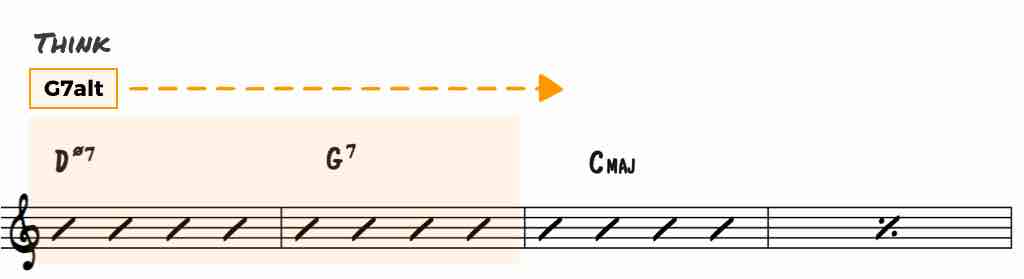

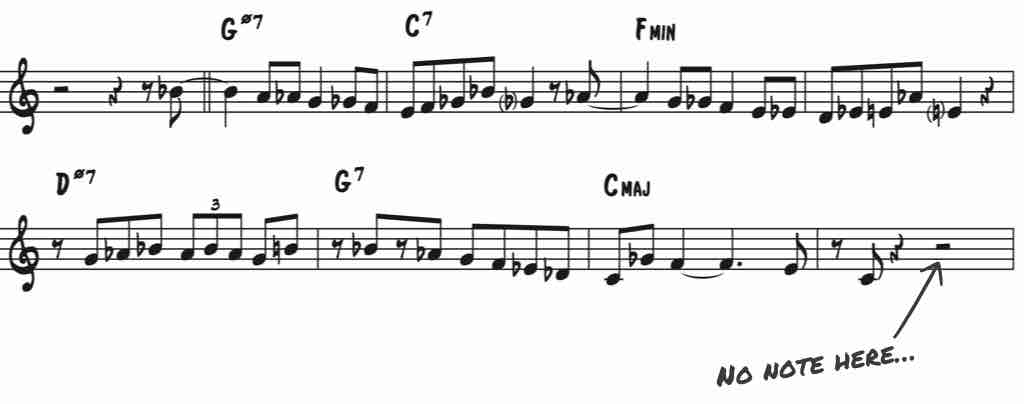

Just as Tadd thought about the first four bars in a different way, he has a unique perspective on the second four as well.

Rather than thinking of a minor ii V, he instead thinks of an altered V7 chord over the entire first two bars. In fact, every note in the phrase comes directly from the Altered Scale.

This is a simple yet very effective technique that all the pros use – think of V7alt over the full two bars.

Sometimes we think that our heroes must be doing something more complex than us, but often they’ve found a simpler way to think that grants them more freedom

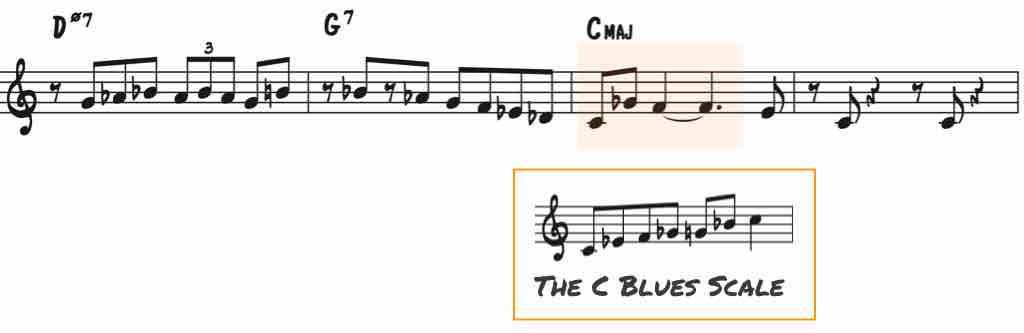

And finally in the last two bars of the first A, he inserts a little blues flavor by using the b5 to 4 of the Blues Scale, a tactic that Miles liked to use as well.

This little hint toward the Blues adds a nice flavor to the melody that couldn’t quite be achieved any other way. And, melodically speaking, it’s a great way to conclude the first A section.

Next, we’ll jump right into the second A section which uses some of the same techniques as the first, but expands on them quite a bit.

The Second A Section

Go ahead and listen to the first four measures of the second A and take note of what you hear…

Does it sound like the first measure wants to resolve? Where does it want to go? What kind of sound do you hear over the second measure? How are the second two bars related to the first 2?

Think about these things for a few minutes and then you’ll be ready to get into the details…

Is that a resolution I hear?

Sometimes when we listen to a phrase, it just sounds like it’s about to resolve. Our ear can sense this and gets ready for the resolution…

And this is what I hear when I listen to the first couple bars of the second A section…to me, it actually sounds like it’s an inserted V7 chord that wants to resolve to a major chord.

But, there’s likely a good reason for this…

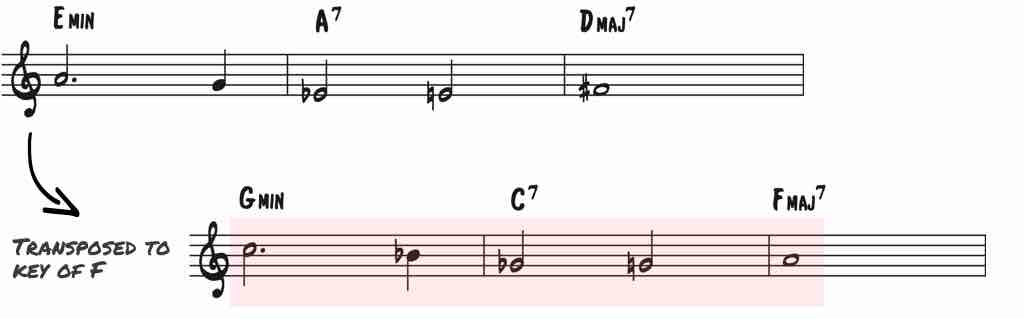

If you look closely at these four notes over the dominant chord, you might have realized that it’s the exact same sequence of notes that’s used in Eddie Vinson’s tune Tune Up (usually credited to Miles Davis).

Have a listen to the tune and you can hear how these 4 notes are the notes of the Tune Up melody…

Here I’ve transposed the melody of Tune Up to the key of F so you can easily see that it’s the same notes used in Hot House.

Now, Tune Up wasn’t recorded until 1953, although it was first performed by Miles in the late 1940s, so it’s unlikely that Tadd Dameron used this as inspiration…

Still, the fact remains that this specific sequence of notes sounds like it wants to resolve, but rather than resolving, the Hot House melody elongates the V7 sound and eventually heads to the natural 9th…

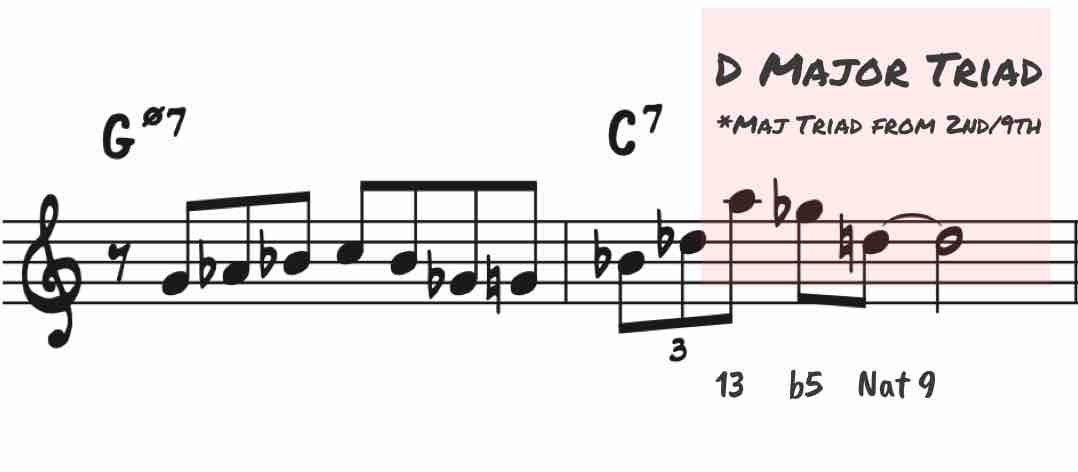

Notice that within this run, lies a major triad structure that starts from the 9th, so in this case, a major triad based upon the 9th of C7, which is D major…

As before with the b5 and 7th over a V7 chord, this can be a tricky combination of notes to hear over a V7 chord.

So, sit at a piano and like before, play a dominant chord in the left hand…and then descend down the major triad structure that begins on the 9th (Another way to think about it is as a triad that’s a whole step up from the root)

Spend some time and get this sound in your ear, as it will greatly aid in hearing and playing this line.

The next two bars are nearly identical to the first two except one slight adjustment – instead of a b9 over the half diminished chord, he uses a natural 9 over the minor chord.

And just like the first two bars of this section, it might sound as though the phrase is going to resolve to you…

But instead of resolving, like the first A section, he implies a V7 chord (Bb7) paired with the F minor, to once again transform the tonic minor chord into a ii V7…

And again, notice the major triad built from the 9th within the V7 sound…

So what can you take from all of this?

First, through this process, you should now be able to hear and conceptualize the first bar of the phrase much more clearly, realizing that it’s the Tune Up melody.

It should make sense to you, and you should hear that it wants to resolve, but doesn’t. That instead, it moves to an interesting phrase over the V7 chord that uses the b9 early on, and the natural 9 later as part of a major triad structure.

Understanding all of these points will make it easier to practice the tune, commit it to memory, and allow you to take the techniques into your own solos.

Okay, next let’s look at the second part of the second A section…

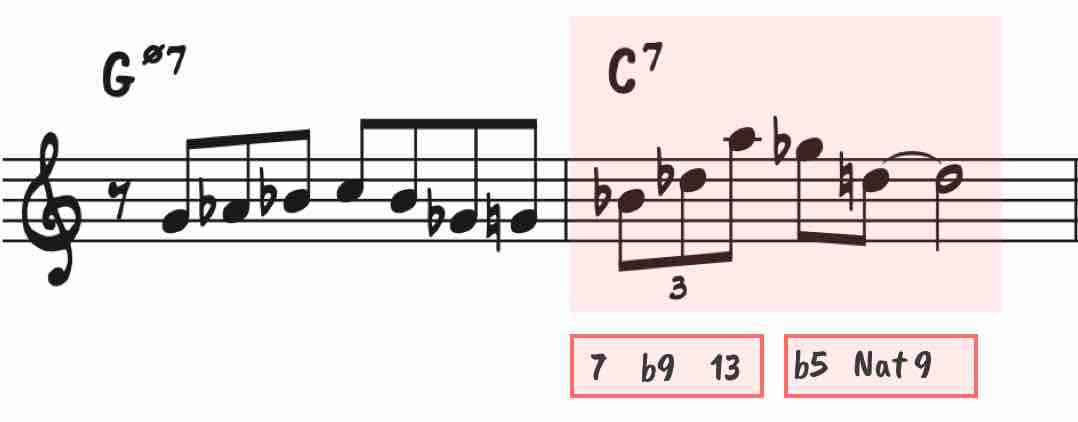

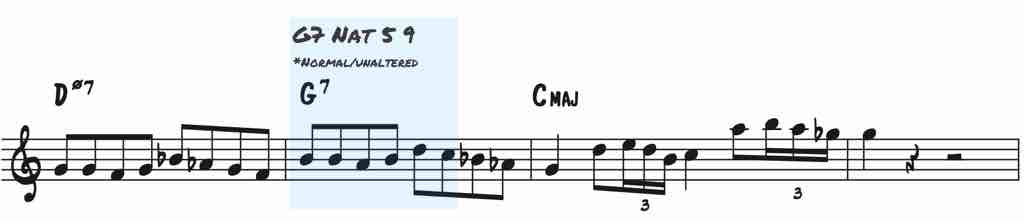

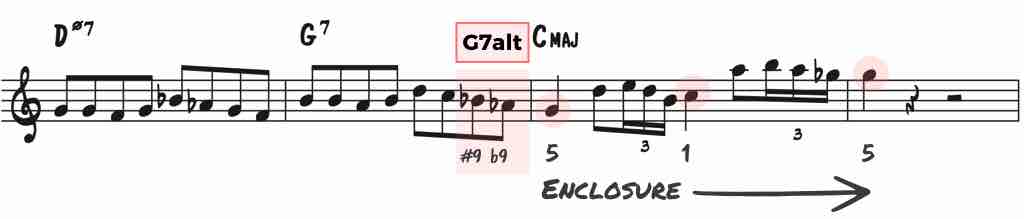

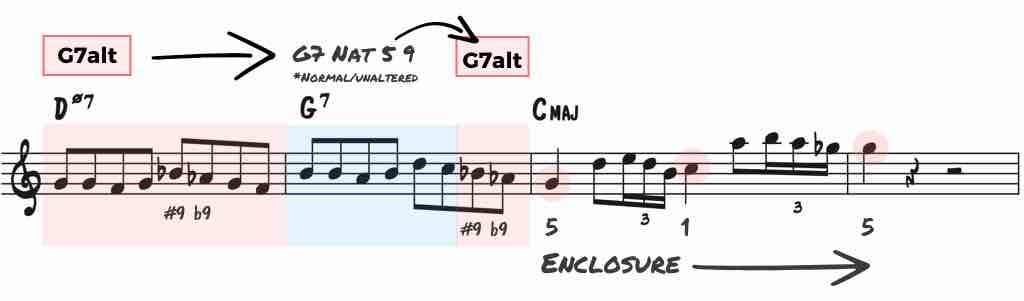

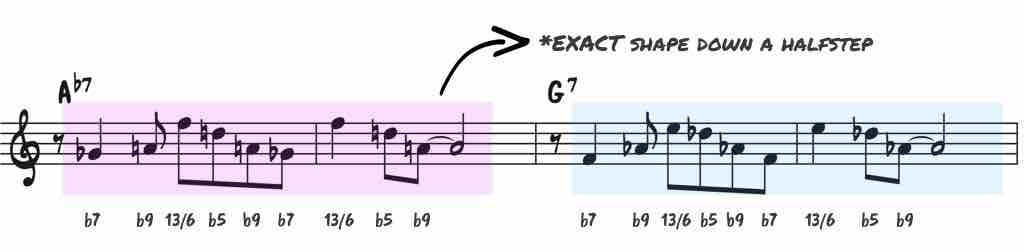

Alternating between different V7 sounds

Go ahead and listen to the second part of the A section and take note of anything that stands out to you.

If you remember from earlier, one powerful technique that we saw was to think of the V7 chord, or an altered V7 chord, over an entire ii V7.

But what if we took several V7 sounds and mixed and matched how we thought over several bars?

Rather than thinking of a single type of V7 chord here, Tadd decides to alternate between several V7 sounds, creating a completely different take on these changes.

Over the first bar he uses an altered V7 sound, emphasizing the b9 and #9…

Then surprisingly, in the next bar he uses an unaltered G7 chord with a natural 9th and 5th.

This is so counterintuitive, to move from an altered sound to an unaltered sound.

And then finally, right before resolving the V7 chord, he goes back to the b9 and #9, and ends with some simple enclosure over the major chord…

So what you end up with is a clever combination of V7 sounds, alternating back and forth between them.

This example should completely change your perspective as to what’s possible over a V7 chord. So much of the time, improvisers commit to a single scale over a V7 sound, not realizing how limiting this can be.

Not only do you not need to think of a scale over a V7 chord, you don’t even have to commit to a single V7 chord sound!

You can choose several approaches to a V7 chord and skillfully combine them all into a single coherent line. The key is to be able to hear all the different V7 sounds, and how each chord-tone sounds against the chord. Only then will you truly have freedom with V7 chords and all their variation.

Once your ear has this ability on an intuitive level, then it’s much easier to weave between various V7 sounds with ease.

Okay, we’ve covered the first two A sections. Let’s get into the Bridge…

Tackling the Bridge

To begin, listen to the first four bars of the Bridge…

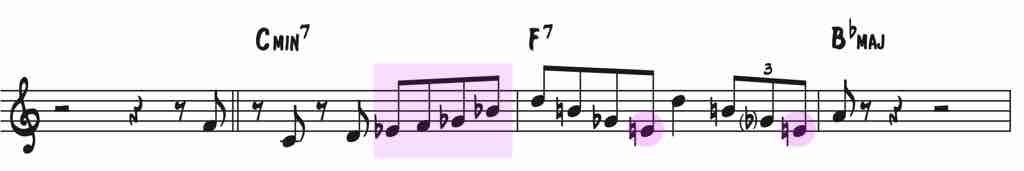

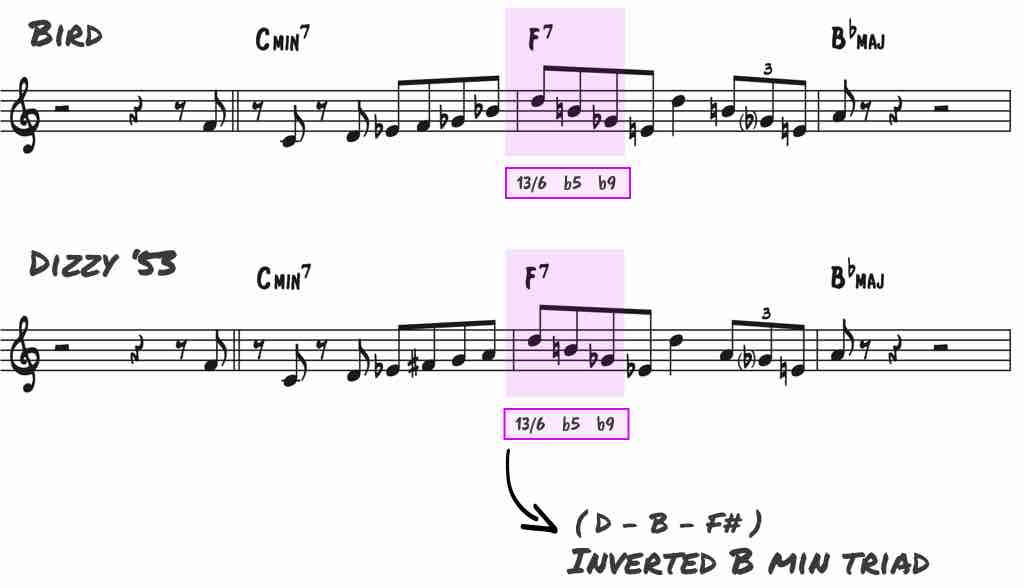

The start of the Bridge to Hot House is not any more difficult than any other section of the tune, however, from recording to recording, Bird and Diz tend to play the melody slightly different each time.

And, it mostly depends upon whether you can more clearly hear Bird in the recording, or if Dizzy’s sound is more front and center, because it would seem as though they never agreed upon the exact notes they would play here.

In the version we’ve been looking at, with Bird’s sound front and center, he ascends the C minor chord with a b5 and actually uses a major 7th on the F7 chord – being on the upbeat and such a fast passage, it works just fine.

Keep in mind, most charts will not look like this, but these are the notes that Bird plays in this specific recording.

Now let’s take a look at 2 other recordings to see what Bird & Diz play elsewhere…

Variations of the Bridge

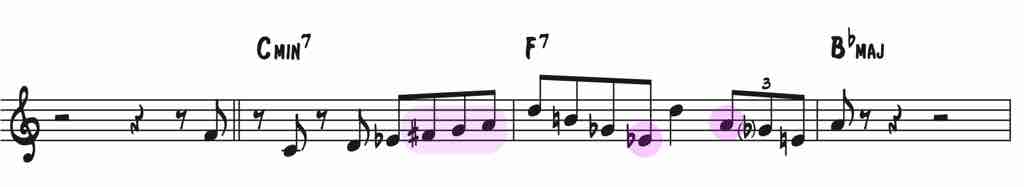

Here is one of the most famous recordings of Hot House, Live in 1951…

At this point in the tune, the start of the Bridge, you can hear a clear rub between what Bird and Diz are playing.

It’s tricky to denote exactly what Dizzy is playing, but it sounds like Bird is playing what he played in the previous recording, but with a natural 5th.

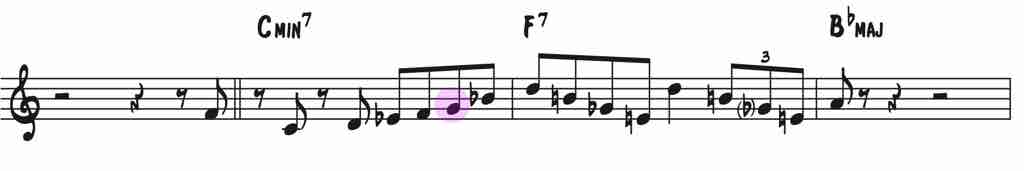

And now, have a listen to this live recording from 1953…

Dizzy’s sound is much more present, giving us yet another variation…

He plays different notes up the C minor chord, leading into F7 – you can really hear that perfect 4th from the A to the D across the bar line, and it sounds as though he’s playing the b7 on the V7 chord instead of the major 7th as Bird did. (This is very hard to hear, and he still might be playing the major 7th)

Again, this is all happening so fast that these slight variations don’t play much of a role. However, if you’re not playing this tune solo, it may be a good idea to get on the same page as to what notes you want to play together.

And, remember that most charts won’t follow these recordings…

They tend to take their best guess as to what the notes should be rather than looking at what the greats played, often using incorrect notes, so just something to be aware of when you’re performing this tune.

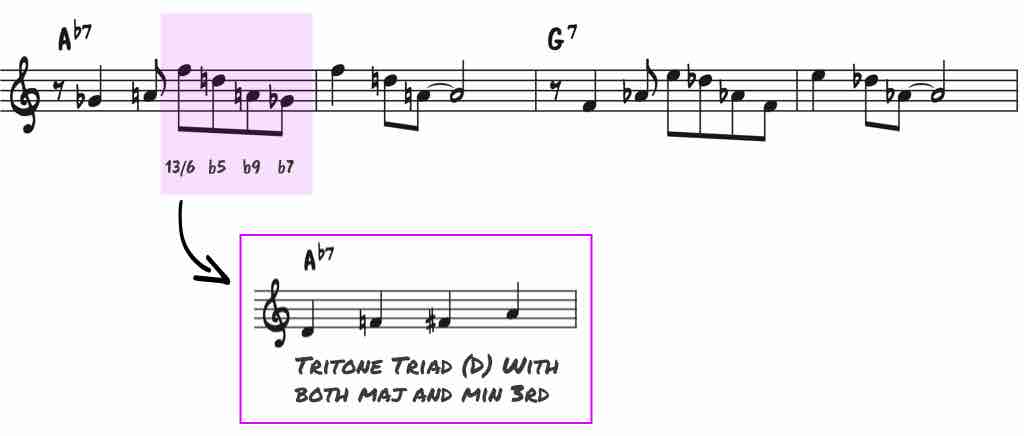

Now that we’ve cleared up some of the variation going on here, I want you to listen to what’s going on over the V7 chord.

Whether you play a major 7th or a dominant 7th at the end of it, the first 3 notes create a very interesting structure over the V7 chord that contains the 13th, b5, and the b9.

And if you look closely, you’ll realize that this is an inverted B minor triad.

A good way to think about this is the tritone minor triad – It’s the minor triad that starts from the tritone of the V7 chord. In other words, B lies a tritone away from F, and we want a minor triad from that note.

Again, as before with unique V7 sounds, sit at the piano and play a V7 chord in the left hand and play the tritone minor triad in the right to train your ear to hear this sound.

This is a great V7 technique that you can add to your arsenal.

And in the remainder of these 4 measures, Tadd wraps up in a similar way that he used previously, by using enclosure. However, this time, he encloses the notes of the relative minor of the major chord.

Using the relative minor structure over a major chord is yet another powerful tactic that you can utilize in your solos.

The Perfect V7 Shape

Finally, we’ve arrived at the last 4 bars of the Bridge and if you’ve been paying attention, these measures shouldn’t be too difficult.

Here he use the same V7 sound that you just learned if you use a dominant 7th on the bottom – the natural 13th, paired with the b5 & b9, and the b7.

Remember, before we thought of the first three notes as the tritone minor triad, but why not get another perspective that uses all four notes?

Sometimes I like to think of this series of notes as a four note cell or scale – a tritone triad containing both the major and minor 3rd.

It never hurts to have multiple perspectives and if you use your creativity, you can find interesting logic that can give you new ways to hear and improvise.

Okay, in these final two bars of the Bridge it’s pretty obvious what’s going on. Dameron’s using exactly the same phrase, simply transposed down a half step to accommodate the new V7 chord.

As we did with some of the other phrases in Hot House, this one is certainly worthy of taking through all keys down in half steps.

Don’t feel obligated to take every single phrase through all keys, but if there’s one that particularly grabs your ear, make sure to give it a go.

And finally we made it…

The last A section of Hot House is the same as the first, although they usually drop out the last 8th note.

So at this point we’ve gone through the entire melody.

As you can see from today’s lessons, there is probably much more to learn from this melody than you ever expected…

Mastering Tadd Dameron’s Hot House

To conclude today, I want you to re-listen to the melody of Hot House with everything in mind that we went over today.

Here are some of the things we talked about that you should pay attention to:

- How he uses chromaticism and how the rhythm makes it work

- The sound of the b5 and 7th over the V7 chord

- How he interprets the first four bars of the A sections as 2 ii V7s

- How he thinks of V7alt over an entire minor ii V7 in bars 5-8

- The place in the second A that uses the “Tune Up” melody

- The sound of a triad from the 9th on a V7 chord (D maj triad over C7)

- How in the second A he alternates between different V7 sounds

- The variations of the start of The Bridge

- How he uses the tritone minor triad (B- triad on F7)

- The V7 shape at the end of The Bridge using 13-b5-b9-7

Hot House is by no means an easy tune, in fact it took me some effort to get under my belt…

But, it was the thinking that we went through today that got me there. Rather than just repeating it over and over and hoping something will click, it helps to understand the logic behind everything.

It’s this type of thinking that will allow you to form deeper connections with the music and better understand how to hear everything. Remember, when we’re talking about the b5 or the b9, or the tritone triad, or anything else…we’re talking about a SOUND.

You have to spend time with the recordings and play the sounds at the piano, and on your instrument, until your ear can make sense of them and they’re no longer just a theoretical definition.

This takes some work, but with today’s lesson you have more than enough at your disposal to tackle Hot House or any other bebop head.

And, not only will you now have an easier time committing them to memory, you’ll be able to extract dozens of useful improvisational devices from these masters of composition and use them in your own solos. Now that’s power.