As he stood in the hallway, the students gathered round. You could see the crowd growing, one-by-one as the people walking by heard what was happening. Harold, animated and speaking with vibrant energy, was sharing his experiences with a group of lucky students that happened to catch him in-between classes.

While I was at music school, pianist Harold Mabern’s spontaneous hallway-lunch-time talks became something you did not want to miss.

A walking encyclopedia of jazz history, tunes and techniques, Harold actually lived it.

He played with greats like Cannonball Adderley, Roy Haynes, J.J. Johnson, Sonny Rollins, Lee Morgan, Freddie Hubbard, Hank Mobley, and Miles Davis, just to name a few!

And Harold, as you can tell from the scene described above, loves to share his experiences and knowledge that he’s picked up along the way.

Having the fortunate opportunity to study and spend time with him for several years, he taught me all sorts of things.

But sometimes the things that have the greatest impact on you are the simplest of ideas…

And then it hit me…

Box after box I unpacked. What could be in this one? More lead sheets, another 10 play-alongs, a manuscript notebook filled with messy lines and chord symbols. What is all this junk? And then, in small barely-legible handwriting, scribbled on a piece of paper, I read something profound…‘Harold told me today that it’s not how much you gain, it’s how much you retain’

This was me as I went through my boxes of junk that I’d been storing at my parent’s house for over a decade.

The whole time I went through them, I thought to myself, “What was I thinking back then?” There were literally dozens of ginormous boxes filled to the brim with books, exercises, and lead sheets.

And, it occurred to me that all the musical information in these boxes was still just, there.

None of it was with me, in my mind, or fingers.

You see, years ago I worked from many of the books in the boxes, practiced the tunes I had lead sheets for, and played the lines I had written out, but very little of it stuck.

A decade later, barely any of that information was with me.

And that’s the thing. When were in the thick of it, we can’t see clearly and more information seems like it’s better.

But it’s not.

It’s all about what information you can retain.

And I’m lucky that out of this “cleaning of the past”, I stumbled upon words of wisdom from Harold that would change how I practice and think about jazz improvisation forever.

“It’s not how much you gain. It’s how much you retain.”

Why retention?

The idea of retention as it relates to everything jazz is extremely important.

When you go up there to perform, it’s just you and your instrument.

It’s not like other activities.

In other things, you have the time and convenience to look things up, think about them, and then make changes as you go.

This is not the case in jazz improvisation.

The only stuff that matters is what you can access in your mind in the moment.

And that’s exactly why retention matters so much.

But there’s a big difference between understanding or agreeing that retention is important and actually using the idea yourself to further your musical development.

If you understand the implications of Harold Mabern’s advice, it will completely change how you practice.

How the idea of retention affects your daily practice

How many things have you practiced that never get used?

I’m willing to bet quite a few. As you can see by my story, I practiced boxes and boxes of information over that years and most of it has fallen by the wayside.

Anything that doesn’t stay with you and get used, is a waste of time.

Think about it. If you practice something whether it be technical, tonal, or conceptual, and it leaves your mind shortly after you worked on it, well before it has a chance to come out when you perform, it has no positive affect on your actual playing.

If you practice in a way that forces retention, then everything you practice makes you a better musician.

Every single day you get better.

When retention becomes a priority for you in terms of your daily practice:

- You practice one thing really well until it’s truly ingrained and you can recall it with ease BEFORE moving on to something else

- You develop a deep knowledge about everything you practice

- You make the information you practice immediately usable

This is the way to get better, but so many people, myself included, tend to practice in a way that does not emphasize retention.

Forget what you think is right. Retention of everything you practice is number one.

Retention and transcribing

Many people transcribe just to write out the notes, but there’s so much more to it than that.

If you’re transcribing in this manner, you’re interacting with the information on a very shallow level. You probably will, by nature of figuring out the phrase, figure out what musical devices the performer is using, however you won’t have the information in your mind to use yourself.

It’s basically like learning how the magic trick is done, but not being able to perform it.

Is that what you want? To know how it’s done?

If that’s the case, then by all means…

But, if you want to perform the trick and be the magician, well then it’s all about retention.

Instead of focusing on transcribing an entire solo (how much you gain), focus on retaining one phrase at a time (how much you retain).

Ditch your manuscript paper, don’t even let it be an option. Force yourself to retain one phrase and only move on until you have it.

You’ll be surprised. Years later you will still know any solo you learn like this.

Retention and language

This same idea carries over to every piece of language you learn.

The only language that matters is the language you retain.

When you’re acquiring jazz language focus on retaining it permanently.

Retention and tunes

This is where people have the biggest difficulties. They seem to think they need to know 100 tunes, so they scramble frantically to memorize a ton of changes from lead sheets.

Stop. It won’t help you become the player you wish to be.

Retain one tune (it’s what you can retain) instead of focusing on more (not what you gain).

The secret of great retention: Your approach

So you probably have a good idea about why you should focus on retention and its benefits, but how do you actually start down this path?

It all goes back to your approach.

Right now, your approach probably uses many things that retain things for you: music notebooks, lead-sheets, fake books, transcription books.

If you approach jazz improvisation as though none of these resources exist and the only thing you have is your ear, your mind, and your instrument, it puts the focus of retention on you.

Imagine you can’t write anything down.

Imagine you can’t look up chord changes in a fake book.

Imagine everything you know has to be in your head.

With this approach, you become the asset. You become the wealth of knowledge. Everything is stored with you internally and it’s with you all the time.

The 4 tools of retention

To develop this approach requires a paradigm shift where you no longer depend on external crutches to retain information for you.

Does this mean you can never write down anything again? No, certainly not.

Remember, these are tools, not rules.

You can write things down, or keep a practice journal, or whatever you like, but you have to “act as if” you have to retain everything.

Do what works for you. If you’re an extremist like me, this means aiming to retain everything and write down very little, but experiment and work these ideas into your practice as you see fit using the 4 tools of retention…

The first tool of retention: Your Ear

Ever notice how something you learned with your ear you can remember much more easily than something you learned from sheet music?

The greatest tool of retention is your ear. But it’s not just about training your ear. It’s about engaging your ear whenever you have the choice to do so.

To retain musical information, you must engage your ear. Period.

Many practice resources and habits take you away from engaging your ear. At any moment in your practice ask yourself, “Am I engaging my ear?”

If the answer’s no, stop and approach things differently.

You should be working on your ear all the time within your practice, and outside of it. That’s exactly why we made The Ear Training Method, a series of progressive ear training exercises that you can take with you wherever you go.

Train your ear, engage your ear, make the DECISION to use your ear to solve your musical problems rather than opting for an easier route, and your ability to retain musical information will skyrocket.

The second tool of retention: Your Mind

Music theory plays an important role in how you conceptualize musical information. It can give you a way to organize, classify, and name what it is that you’re trying to remember.

Basically, music theory gives you a way to talk about musical information and allows you to clearly understand things like how each chord-tone relates to the harmony.

Use this knowledge in conjunction with your ear to form an even stronger connection with what it is your trying to retain.

If a line uses the b9, know this, or if it ascends to the #11, take note of it and listen closely when the line arrives there, making sure to connect the intellectual information, the fact that it’s rising to the #11, with the aural information – what the #11 sounds like.

All these relationships between chord-tones and the harmony must be so ingrained that you “Just Know” exactly what they are – you shouldn’t have to think about what the #5 of of Ab7 is or the ii chord that precedes F#7.

All theoretical information should be automatic. The secret to this is visualization. If you want over 100 audio exercises to practice this concept, our Visualization eBook drills all these relationships until they’re firmly implanted in your mind.

Theory is just like practicing in terms of retention. You can know all the theory in the world, but it’s what you can retain and recall without thinking that will actually help you in a playing situation.

Study theory through the perspective of retention and visualization, and over time, the musical relationships will become automatic.

The third tool of retention: Observe Uniqueness

Humans are wired to notice differences and retain them much more easily than similarities.

When you’re studying a phrase from one of your heroes, a specific tune, or anything musical that you want to retain, ask yourself, “What makes this unique?”

The answer to this single question gives you something to latch on to. Something that will stick out in your mind when you go to recall it. Something that distinguishes it from everything else.

This uniqueness can be anything. The key is making it personal.

What stands out to YOU?

Not, what stands out to your teacher, or to a friend. To you.

The best way I’ve found to do this is to listen. Supposing you transcribed a line you like, well instead of studying it and theoretically figuring out what’s cool, get away from anything you’ve written down or figured out for a moment, and just listen to the line.

What sounds most unique to you?

That’s what it’s all about. What sounds most unique, not what theoretically is most unique. Then, once you’ve listened to it and determined what sounds most unique to you, pull it apart and figure out an explanation for why it sounds so unique.

Again, it’s completely up to you. If you think it sounds unique because of the shape of the line, then great. Or perhaps it’s the way the performer uses a certain interval. Fine.

Any way you can understand the uniqueness gives you a way to think about the line.

The fourth tool of retention: Repetition

Repetition is the key to retaining information. But, it must be repetition in the right way.

What’s the right way?

The right way is:

- Slow – play as slowly as you need to execute with perfection

- Accurate – play it correctly every time

- Mindful – keep in mind all the other tools while you repeat. This means you’re engaging your ear, you’re aware of the theoretical knowledge you have in your mind, and you’re cognisant of the uniqueness of what you’re practicing.

If you repeat information in the right way, you will retain it and be able to use it at your discretion.

Putting retention into practice: making vivid memories

Now that you have a good idea why retention matters so much, let’s put everything we’ve talked about into practice…

Have a listen to John Coltrane playing Just Friends:

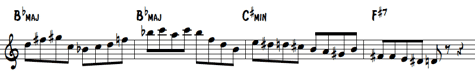

Although many phrases that he plays catch my ear, I’m particular drawn to the phrase he plays at 4:10:

Listen to it at full speed here:

And now at half speed:

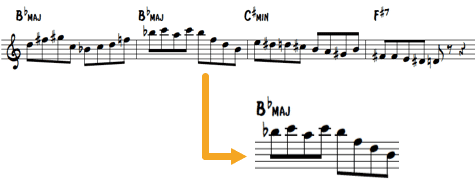

From this line, there’s a piece of it that stands out to me that I really like. So first, I’d extract this piece of language:

Now, how would I retain this? How would I keep the information encoded within this piece of language with me permanently?

First, I can tell you how NOT to retain it: write it out in a all 12 keys and sight-read it over and over.

This engages neither your mind nor your ear.

To retain something, you must make a vivid memory:

- Can you hear the intervals in the line and hear the color of each chord-tone as it relates to the harmony?

- Do you have a clear mental connection between each chord-tone and how it relates to the harmony?

- Do you understand the unique qualities that make-up what it is you’re trying to retain?

- Have you repeated the information slowly and correctly over and over?

So first things first…

We need to hear each interval and chord-tone in the piece of language, while simultaneously developing a mental relationship to the chord-tones as they relate to the harmony.

These two keys, the ear and mind connection, are vital to creating strong retention.

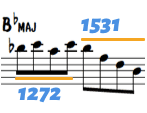

Slow the line down. Then hear and mentally understand the relationships and sounds going on…

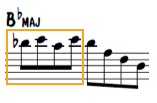

And while you’re implanting this information, observe the unique qualities that will stick out in your mind. Remember we’re wired to highlight differences:

What’s the uniqueness to me?

The shape of this 4-note-group is what I think really makes it sound different. By observing this feature, I’ve found something that I can use to think about it, classify, and even name if I like.

Then, all that’s left is to repeat the line over and over, slowly and correctly, keeping everything we’ve done in mind the whole time.

The 30 day retention challenge

Sound like retention is something you should try in your own practice?

It should. And if you give it a shot, you will never think about practicing the same.

Rather than “putting in your time” or “practicing for practicing sake”, you’ll think of using your practice time to retain the information that you’re discovering.

Everything you practice will become useful and applicable.

You’ll feel as though you’re truly developing and growing as a musician because you’ll be forcing yourself to internalize information rather than allowing it to hover in the external world.

Try it for 30 days.

No lead sheets. No manuscript paper. No crutches.

Just you, your ear, your mind, and your instrument.

It’s not easy and you’ll practice much less material than you ever have in your life, but on a much deeper level.

And at the end of those 30 days, you’ll actually have information that’s stuck with you. Information you can use and build upon.

Remember, it’s not how much you gain, it’s how much you retain!