Creativity in its most basic form is simply the act of taking something old and making it new. Whether you’re a novelist, an architect, an engineer or an improviser, artistic creation stems from a desire to make something new within the existing confines of your craft. To put a personal stamp on your art form and to have your voice heard in some way. For musicians this revolves around our personal interpretation of the fundamentals of music: sound, melody, rhythm, and harmony.

However, creative inspiration doesn’t just appear out of the blue like a bolt of lightning, instead it slowly reveals itself through the diligent study of previous generations and the mastery of established skills. Schools of thinking must be studied, styles are to be imitated, and techniques will need to be ingrained.

“Creativity is knowing how to hide your sources.”~Albert Einstein

The study of jazz improvisation is a perfect example of the progression of creating the new from the old. This idea of continual reinvention and self expression is prevalent throughout the history of this music and you’d be hard pressed to find a lasting piece of music or style that didn’t have a direct line back to the creative work that came before it.

Take the process of transcribing a solo for instance: starting with the musical language from a previous generation, learning it slowly and eventually making it your own. An old musical language ingrained and interpreted into new musical language.

However, this concept of musical reinvention and adaptation isn’t only limited to the practice of learning solos, creativity can also be applied to the Great American Songbook.

Below we’ll look at two common techniques utilized by the greatest improvisers in expressing their inner creativity through the popular songbook: the Contrafact and Reharmonization.

Jazz Contrafacts

A contrafact is a new melodic composition written over the chord progression to a preexisting tune.

For example, Charlie Parker’s tune Ornithology is a contrafact of the standard How High the Moon – a new melody composed over an existing chord progression.

The contrafact stems from a desire to create something new, a creative inclination to take a different approach within an existing framework.

However, the contrafact is not an exclusively jazz phenomenon, the tradition of taking an existing song and altering it started in the 16th century. During this time the lyrics for secular songs were often replaced with religious text. In doing so the harmonic backdrop was preserved while a more “meaningful” text was applied.

This technique was adopted by and especially suited for the improvising musicians of the 1940’s. These musicians started exploring and performing a collection of popular tunes that we still play today.

In informal jam sessions and club dates these pop tunes were used as “proving grounds” for new musical ideas. Musicians like Parker and Dizzy Gillespie were not dealing with lyrics, but instead simple pop melodies that they replaced with their own creative inventions.

“I found that by using the higher intervals of a chord as a melody line and backing them with appropriately related changes, I could play the thing I’d been hearing.”~Charlie Parker

Parker expresses this musical sentiment referring to his experimentation over Ray Noble’s standard Cherokee. Take a listen to Parker’s contrafact KoKo on Cherokee:

Check out this NPR story on KoKo for a little more insight.

Tunes like Ornithology, Koko and Donna Lee were the natural result of the experimentation and study of these standards.

It’s important to keep in mind though, that an effective contrafact is not just another blues head or rhythm changes tune or haphazard melody over a familiar progression. For the greatest improvisers, the contrafact was a way to explore a new harmonic, melodic, or rhythmic concept – to instantaneously stick with tradition and move it forward.

Here are a few common jazz contrafacts that you’re probably encountered:

- What is this thing Called Love = Hot House

- How High the Moon = Ornithology

- Indiana = Donna Lee

- Sweet Georgia Brown = Dig

- You Stepped out of a Dream = Chick’s Tune

- Just You, Just Me (Just Us -> Justice) = Evidence

- Lady Bird = Half Nelson

- All the Things You Are = Prince Albert

Charlie Parker Contrafacts

Charlie Parker is without a doubt one of the most important innovators in American music.

Even today many of his tunes continue to be studied and performed by improvisers around the world. However the majority of these tunes aren’t free standing through composed musical pieces, they are contrafacts or “head charts” written on top of blues changes and rhythm changes and other popular standards.

Bird used the popular standards of his time as a vehicle for his musical vision, a way to bring to life the musical ideas he was hearing in his head. Coming through the preexisting chord progressions of these tunes you hear the hallmarks of Parker’s musical style: his rhythmic acuity, harmonic sophistication, and a linear melodic ease.

Here are some of the contrafacts that Bird wrote over the chord progressions to Rhythm Changes and Blues:

Rhythm Changes:

Anthropology

Celerity

Chasing the Bird

Constellation

Kim

Moose the Mooch

An Oscar for Treadwell

Red Cross

Shaw Nuff

Steeplechase

Thriving from a Riff

Blues:

Au Privave

Billie’s Bounce

Bloomdido

Cheryl

Cool Blues

Laird Baird

Mohawk

Now’s the Time

Parker’s Mood

Relaxin’ at Camarillo

Si Si

Lennie Tristano Contrafacts

Another improviser searching for a new sound within the popular repertoire of the 1940’s was the pianist Lennie Tristano.

Like Bird he took the chord progressions of popular tunes and created new melodies that incorporated the musical concepts he was working on. Listening to the tunes of both players, the concept of the contrafact is the same, however you can immediately hear how Tristano’s melodies reflect one unique musical style and Bird’s another.

Below are some common Tristano contrafacts composed over the chord progressions to some well known standards:

Ablution = All the things you are

April = I’ll Remember April

Crosscurrent = I Got Rhythm

Lennie-Bird = How High the Moon

317 East 32nd = Out of Nowhere

Also, check out this informal duo recording of Charlie Parker and Lennie Tristano playing “I Can’t Believe that You’re in Love with Me” to hear these two styles back to back.

Reharmonization

The second technique of reinventing the standard songbook used by improvisers is reharmonization – altering a chord or sequence of chords in a song’s progression while retaining the original melody and structural outline of the tune.

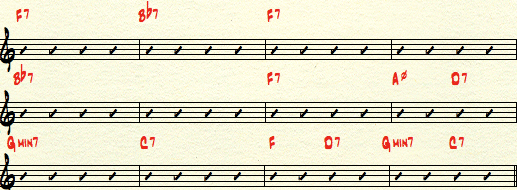

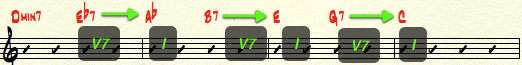

After experimenting with altering the melody through the contrafact, the next logical step is to actually change the chord progression of a tune – reharmonization. For example, take a look at the normal 12 bar blues progression and Bird’s reharmonization of the blues:

12 Bar Blues

Bird Blues

Certain chords have been altered or substituted to create a more dense harmonic motion, yet the overall form of the tune remains the same. You can also check out this article, Basic Bebop Reharmonization, for more on this concept.

Here are a few common reharmonizations that you’ll probably encounter at some point in your musical journey:

Blues = Blues for Alice

Rhythm Changes = Eternal Triangle

How High the Moon = Satellite

Rosetta = Yardbird Suite

Coltrane Reharmonizations

“I’ve found you’ve got to look back at the old things and see them in a new light.”~John Coltrane

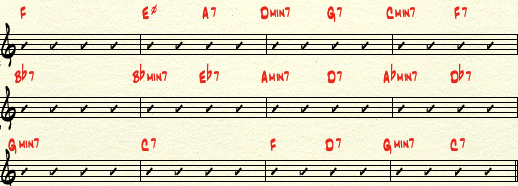

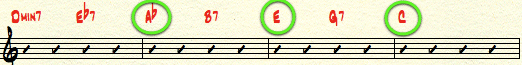

In the late fifties John Coltrane began to experiment with reharmonization and the concept of non-diatonic or chromatic third relationships. Below is an example of this reharmonization technique he created on a ii-V7-I in the key of C.

In Coltrane’s reharmonization of the standard ii-V7 -I progression shown above, the new key centers are Ab, E and C. The basic outline is still D-7 to G7 to C, but he doubles the harmonic motion and introduces new key centers moving by chromatic thirds.

Additionally, related dominant chord (V7) is then placed before each of the key centers to accentuate its arrival.

Below is a list of tunes that Coltrane tunes and reharmonizations that utilize the above chord relationship:

- Body and Soul

- But not for Me

- Fifth House = Hot House

- Countdown = Tune Up

- Spring is Here

- Satellite = How High the Moon

- 26-2 = Confirmation

An evolving standard

Perhaps the best way to illustrate the use of contrafacts and reharmonization is to take one standard and look at how different musicians have played it. Let’s take Cole Porter’s song “What is this thing called love.”

What is this thing Called Love: Cole Porter, 1930

Here is the Clifford Brown and Max Roach arrangement of What is This Thing Called Love.

a) Hot House: Tadd Dameron, 1945

This melody composed by Tadd Dameron reflects the hallmarks of the bebop movement, a chromatic melody, rhythmic complexity, and altered chord tones.

b) Subconscious-lee: Lee Konitz, 1949

Lee Konitz studied with Tristano and the influence of the pianist is obvious in his composition.

c) Fifth House: John Coltrane, 1959

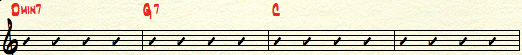

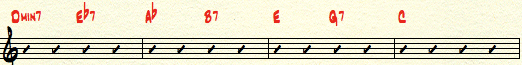

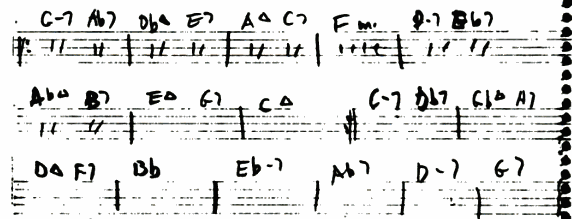

Coltrane took the progression to What is This Thing Called Love? and applied his chromatic third reharmonization.

Below is an excerpt from Coltrane’s notebook showing his reharmonization Fifth House. Here you can clearly see the chromatic 3rd relationships he’s implying in his solo over the ostinato bass line in the A section and again the same reharmonization on the bridge.

All four of the above tunes are based on that original Cole Porter chord progression and melody. With Tadd Dameron’s Hot House and Lee Konitz’s Subconscious-lee you can hear the creative approach of the contrafact – new melodic content over an existing chord progression.

However in Coltrane’s Fifth House you can immeadiately hear how a reharmonization can completely change the character of the original tune while retaining the original tune form.

The same process, for instance, could also be done with How High the Moon:

a) Ornithology

b) Lennie – Bird

c) Satellite

How to approach contrafacts and reharmonizations

Improvisors have been playing the same core group of standards for the last sixty or more years. In that time, a lot of musical innovation has happened and much of it has been applied to the standard songbook.

Oftentimes when we first get into jazz we listen to the newest albums, the newest artists, and the newest tunes. We go directly for the hippest stuff (like contrafacts and reharmonizations) and try to start learning improvisation right then and there. It’s easy to forget that everything new and creative has a point of origin.

Trying to start your musical education with a reharmonization or a contrafact is like jumping into a movie trilogy and starting with the third installment. It’s confusing and maddening to keep up with the story. What’s going on? Who’s that guy? Wait…what??

If you skip the background story you’re going to be very confused and discouraged. The same is true if you jump right to Satellite without understanding or knowing How High the Moon. Approached like this both tunes easily seem unrelated and completely different.

In reality, the group of standards that musicians often play are more connected and related than we think. Time and again we encounter the same progressions and types of harmonic movement in the tunes we’re learning and performing. Over the years as the music evolved so did the approach to the collection of popular tunes.

To truly understand the evolution of the Great American Songbook you need to start at the beginning, and this means understanding where your favorite contrafacts and reharmonizations come from.