The Altered Scale, also known as the Super Locrian scale, allows access to the most beautiful tensions of a dominant chord in a flash. But using this scale effectively is not easy. In this lesson, we’ve assembled the keys to utilizing the Altered Scale to its full potential.

We’re going to get into all of the specifics of this scale and a whole lot of concepts surrounding it.

We’re going to talk about:

- What chord alterations are and how to think about them

- How to hear chord alterations

- Exactly what the Altered Scale is

- Where it comes from and why it’s so popular today

- Where you can use the Altered Scale

- Some practice exercises to get you started

And a whole lot more! So let’s get into it by first getting into some details about alterations themselves…

You see, the Altered Scale didn’t really become widespread until Chord-Scale Theory became the general method of teaching jazz improvisation.

With the idea that scales could be applied to chords and that scales could be derived as a series of modes from a parent scale, the Altered Scale swept the jazz education world by storm.

But to use this powerful scale musically in in your solos is no easy feat – you first have to understand a little bit about alterations and see exactly how they fit into the chord before you start unravelling the intricacies of the scale…

What are chord alterations?

Let’s take a dominant chord, a G7 chord…

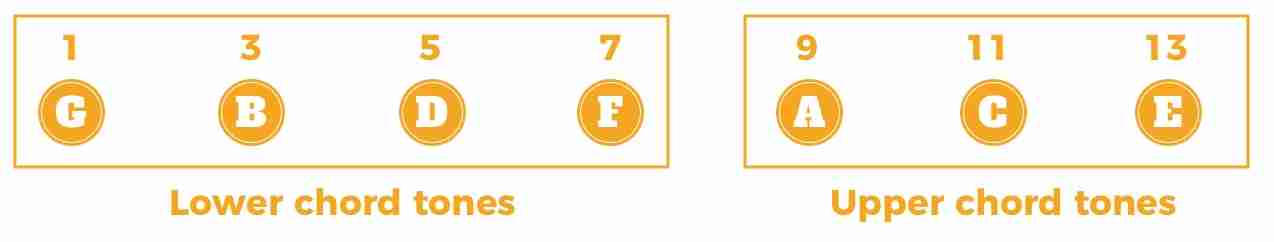

The basic chord tones of this seventh chord are 1-3-5-7, G-B-D-F…

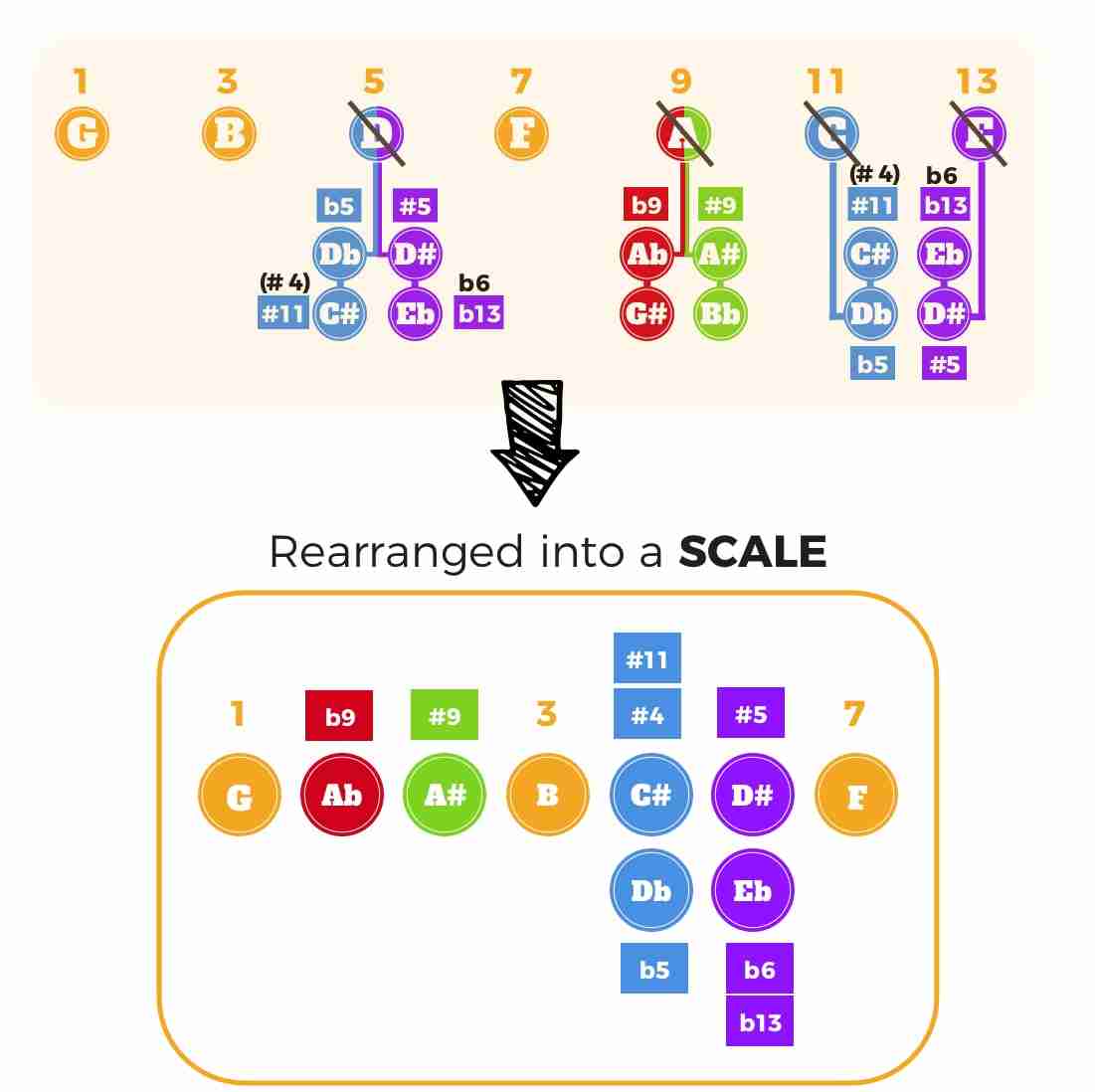

And then, if we extend this chord all the way to the 13th, you can see how the chord structure is made up of the lower part of the chord, the 1-3-5-7 and the upper part of the chord, the 9-11-13.

This is how I like to think about a chord, in two distinct pieces…

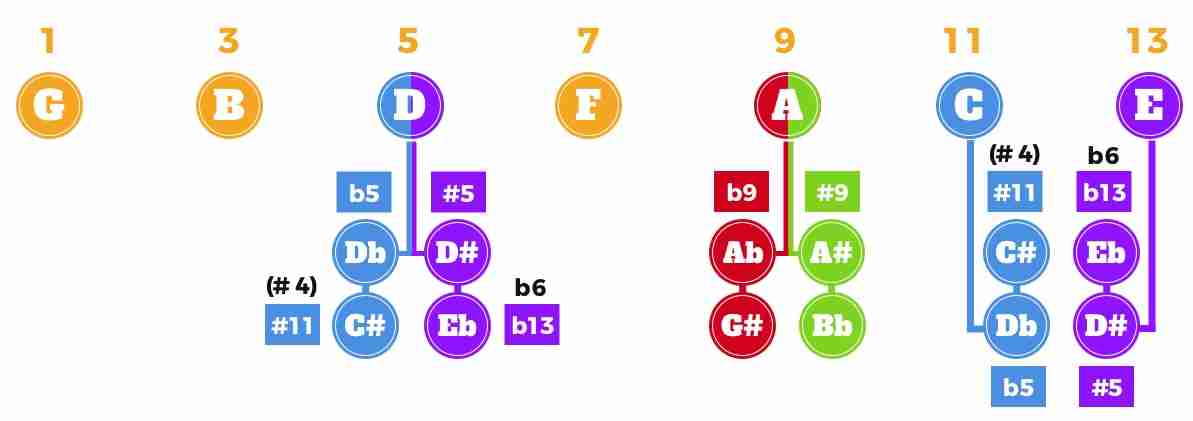

Now when people talk about alterations of a dominant chord, they’re generally talking about alterations to the 9-11-13, or the 5th of the chord.

Typically, the root, the 3rd and the 7th of the chord have to remain intact within the chord because that’s the essence of what makes the chord sound like a dominant chord.

If you take these essential chord tones away, the chord sound will no longer sound like a G7 dominant chord, so those tend to remain.

However, the 9-11-13 and the 5th can be altered, meaning these tones can be raised a half-step, or lowered a half-step, to add a beautiful tension to a dominant chord, while not confusing the dominant sound.

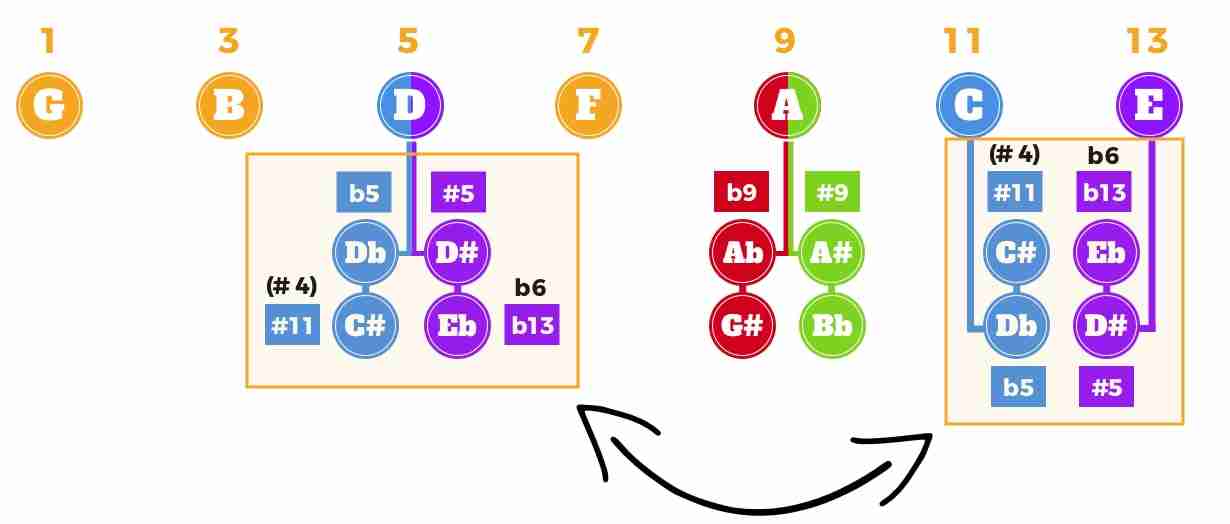

Do you notice the overlap between the alterations to the 5th, and the alterations of the 11th and 13th?

This is subtle, but very important…

Lowering the 5th of the chord is equivalent to raising the 11th (which is the same note as the 4th), and raising the 5th is the same as lowering the 13th (which is also the 6th). Let that marinate for a minute before moving on…

Next, realize that there are only 4 possible alterations on a dominant chord.

We can:

- Flat or Sharp the 9th

- Raise the 11th (Same as flatting the 5th)

- Flat the 13th (Same as raising the 5th)

This overlap between the 5th and the 11th and 13th causes a lot of confusion among improvisers, so watch out for this…

Make sure you understand that there are different ways to interpret alterations depending upon whether you see them as altering the 5th, or altering the 11th or 13th, but that they’re affecting the same note.

The only difference between the two is this: if a chord specifically says to alter the 5th, as in G7b5, then a natural 5th is not typically included in the chord voicing because it’s specifying an altered 5th.

But, if the the composer specifically says to alter the 11th, like G7#11, this refers to the upper chord-tone, the 11th, so the natural 5th might be included in the chord voicing.

Keep in mind that this is not a rule set in stone, but definitely a guideline to be aware of.

Okay, now that you understand what alterations are and where they occur in a dominant chord, let’s talk about how these show up in the Altered Scale.

What is The Altered Scale?

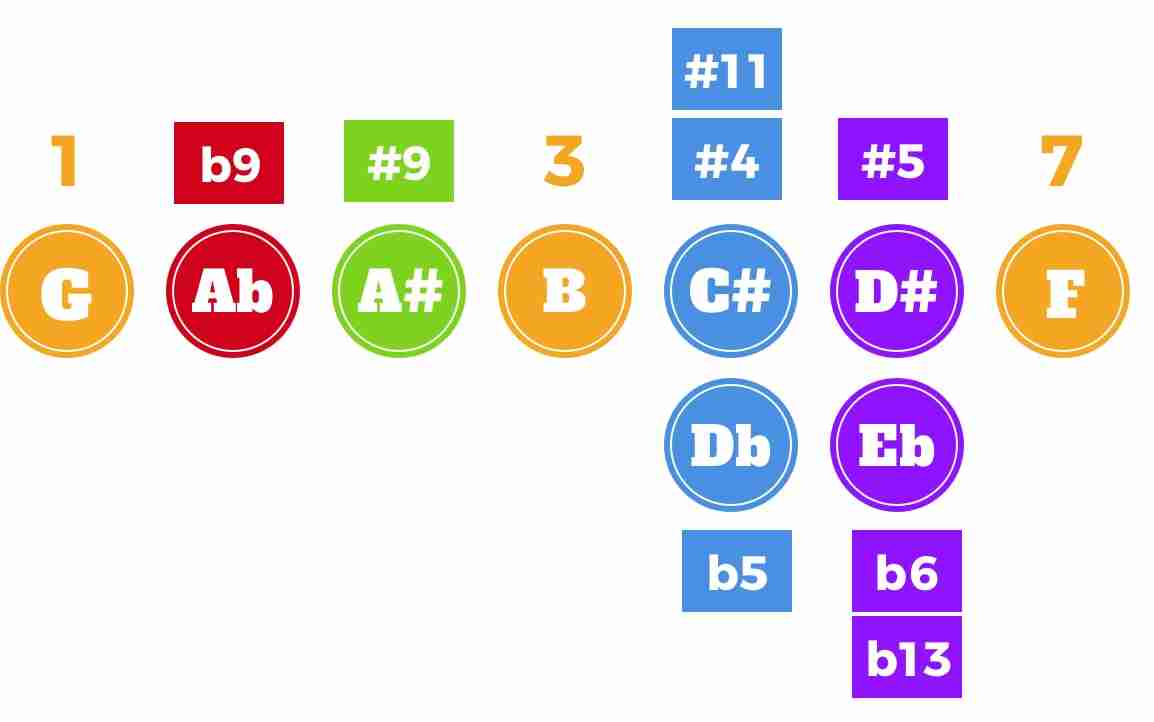

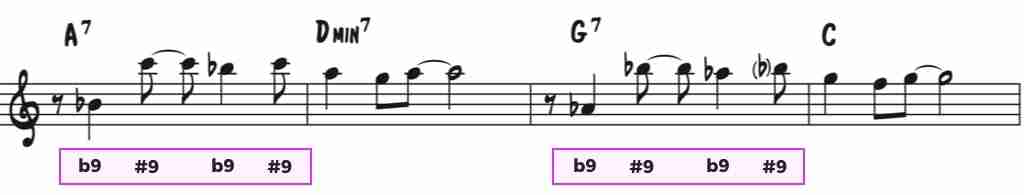

The Altered Scale is a scale that’s applied to a dominant chord, with the aim of giving the improviser easier access to the altered tensions, the altered chords tones that we just talked about: b9, #9, b5/#11, #5/b13

The scale, as most scales tend to do, starts on the root of the chord…it then goes to the b9, the #9, the 3rd, the b5/#11, the #5/b13, and the 7th

And you can easily see, the scale is the G7 chord up to the 13th, with all 4 possible alterations included and then rearranged into a scale (a linear sequence of notes, 1-2-3-4-5-6-7) rather than a chord (a vertical sequence of notes 1-3-5-7-9-11-13)…

So notice, the only notes that are not altered (raised or lowered) are the root, the 3rd, and the 7th. All of the other notes of this scale are an altered tension, which makes it a powerful group of notes.

The only problem being, how do you think of this group of notes easily?

I mean, unless you’ve worked on visualizing chord tones, you probably can’t muster up the b9, #9, b5, or #5 of a dominant chord in an instant.

Well, jazz education has come up with a nifty little shortcut for deriving the Altered Scale and it’s not a bad place to start…

And this little trick goes back to where the Altered Scale actually comes from…

Where does the Altered Scale come from?

The Altered Scale comes from a unique scale called the Melodic Minor Scale.

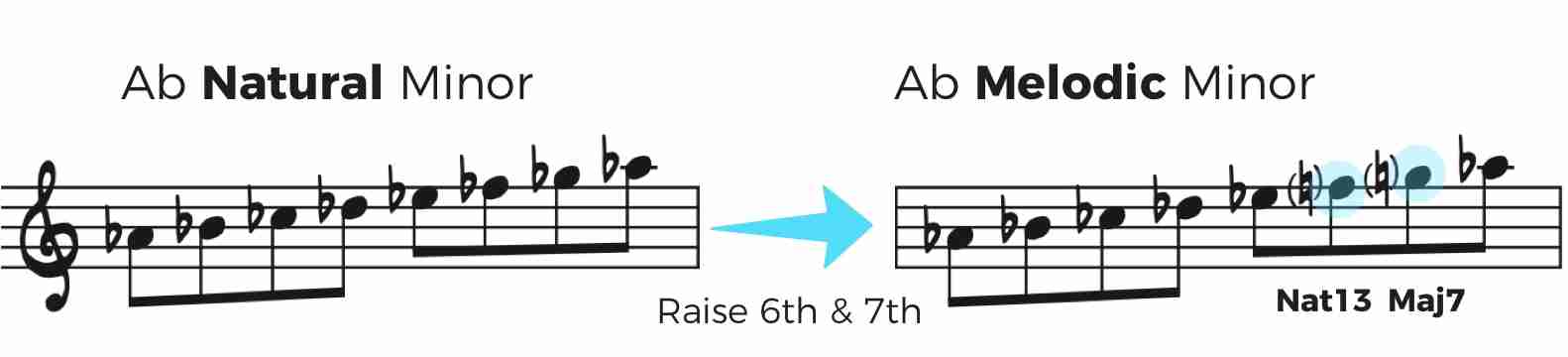

Now there are a few ways to think about this scale, all depending upon your reference point. If you’re thinking about it from the Natural Minor scale, then you would need to raise both the 6th and 7th degrees to transform it into the Melodic Minor.

So if you take Ab Natural Minor (you’ll see why we’re using Ab in a minute) and raise these two note, you get Ab Melodic Minor…

Keep in mind, although you’re raising the 6th degree, I like to think of the 6th degree of the Melodic Minor as a natural 6th because it’s really the natural 13th of the minor chord, rather than a b13th like the Natural Minor scale uses.

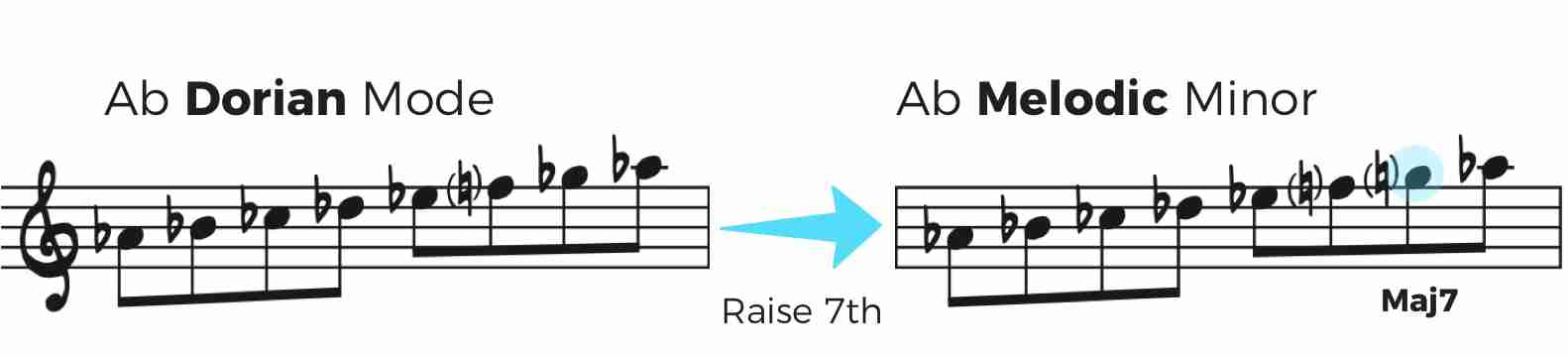

Now another way that makes a lot sense for jazz players is thinking about the Melodic Minor as the Dorian Mode with a major 7th.

Taking Ab Dorian and raising the 7th from Gb to G natural, the major 7th, we get the Ab Melodic Minor scale:

Using Dorian as your reference point tends to work really well for jazz players because we tend to think of this scale as the baseline scale for minor chords.

That natural 13th sound in Dorian is something that us jazz players generally like to include in our minor chord/scale concept.

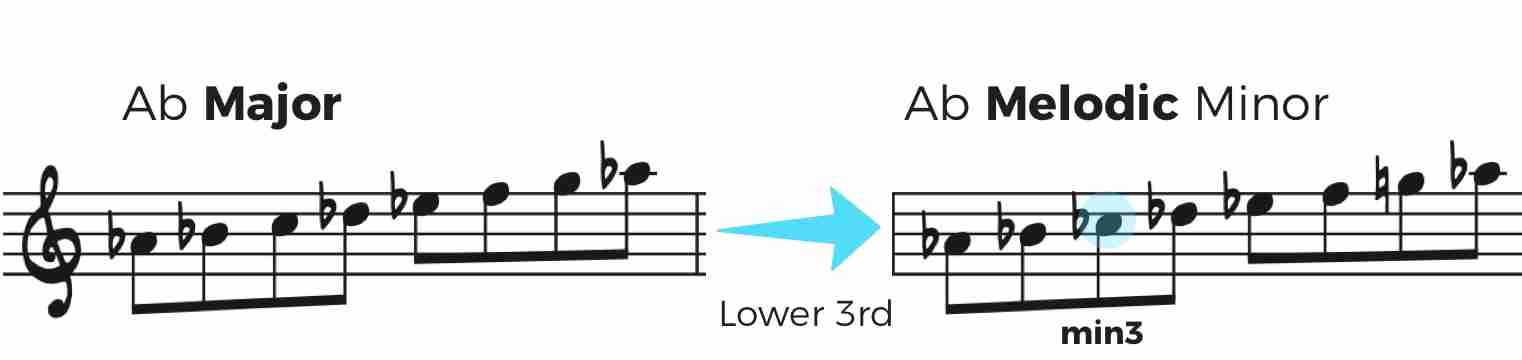

Still, you could just as easily think about Melodic Minor in relation to the Major Scale by lowering the 3rd, for example, Ab Major Scale with a minor 3rd.

When it comes to thinking about Melodic Minor, all of these ways are totally acceptable and eventually your brain will get rid of any sort of calculation of the scale – you’ll just know your Melodic Minor scales as their own thing, just like you know the 12 Major Scales.

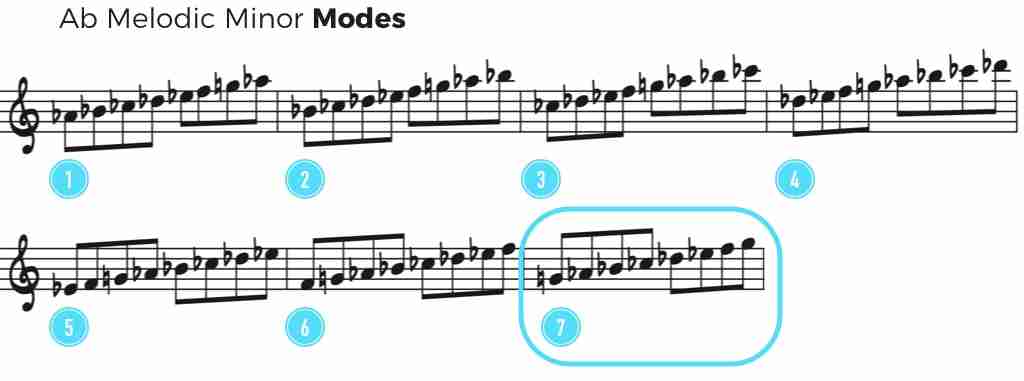

Okay, so now that you have the Ab Melodic Minor scale, let’s take a look at the modes of the scale (Go here for a refresher on modes).

Modes are essentially a scale within a scale

You can start the Ab Melodic Minor Scale from 7 different notes, so it makes sense that there are 7 modes of the Melodic Minor Scale.

And the mode we’re interested in is the 7th mode of the scale, the one that starts on G…

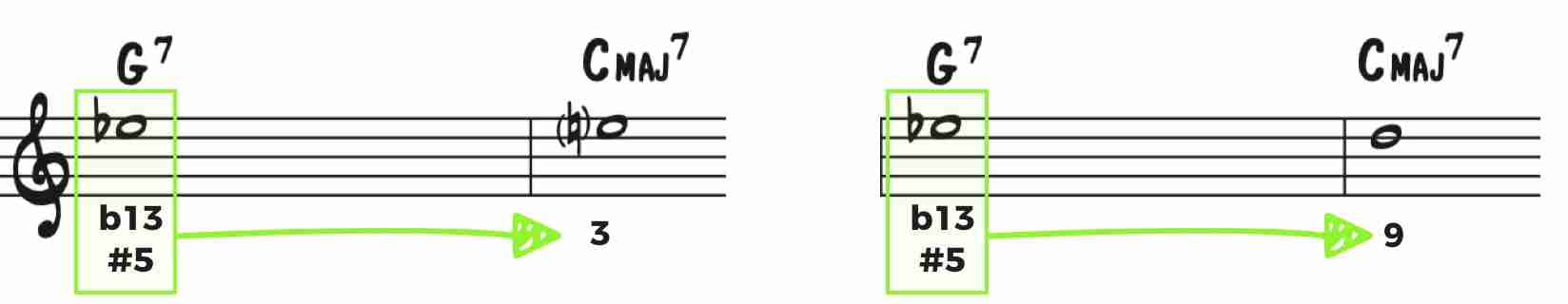

This 7th mode of the Melodic Minor Scale is the G7 Altered Scale that we’ve been talking about this whole time and this is where it comes from – directly from the modes of Melodic Minor.

And this leads us into the little trick that every jazz student today learns to get to the Altered Scale quickly…

The Altered Scale Shortcut is a simple way to arrive at the appropriate Altered Scale for a particular V7 dominant chord, and it goes like this…

Go up a half step from the root of the dominant chord and play the melodic minor scale that starts from that root.

On G7, go up a half-step to Ab, and play the Melodic Minor scale from that root, Ab, and voila, you’re playing the G7 Altered Scale.

So, in other words, to find the Altered Scale for G7, you play the Ab Melodic Minor Scale from G to G (and obviously the Cb is actually B, the 3rd, in G7 but I’m leaving it as Cb here so you can see the relationship with Ab Melodic Minor)

Now this shortcut is worth learning because your brain sometimes needs something to grab onto at first, a reference point, but over time, you want to do away with this shortcut…

After all, jazz is a real-time activity, so you have no time as your playing to calculate or plan what it is you’re going to play – you just have to know the information.

But the more you play, and the more you understand and familiarize yourself with the actual alterations within the scale and how they relate to the chord, the less dependent you’l be on the shortcut.

Where do you use the Altered Scale?

Now that we know what the Altered Scale is and where it comes from, let’s talk about where you use it…

When I was younger, I would see a dominant chord in a tune and I would think…I’ll use the Altered Scale! It gives me all the cool notes, so it will sound great, right?!

But the truth is, using altered notes over a dominant chord requires a certain context for them to sound good.

The dominant chords to play it over

You don’t want to use alterations over any dominant chord, you want to use them over a dominant chord that has a strong resolution directly after it.

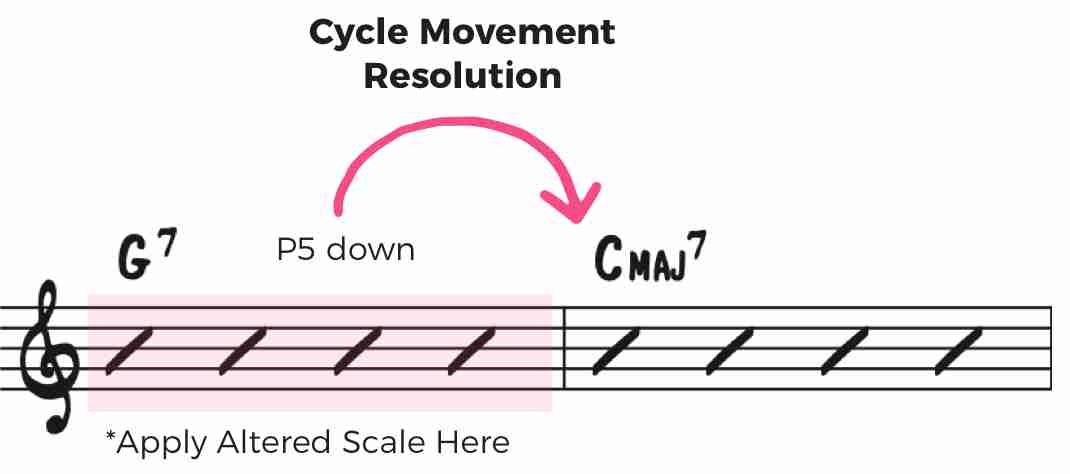

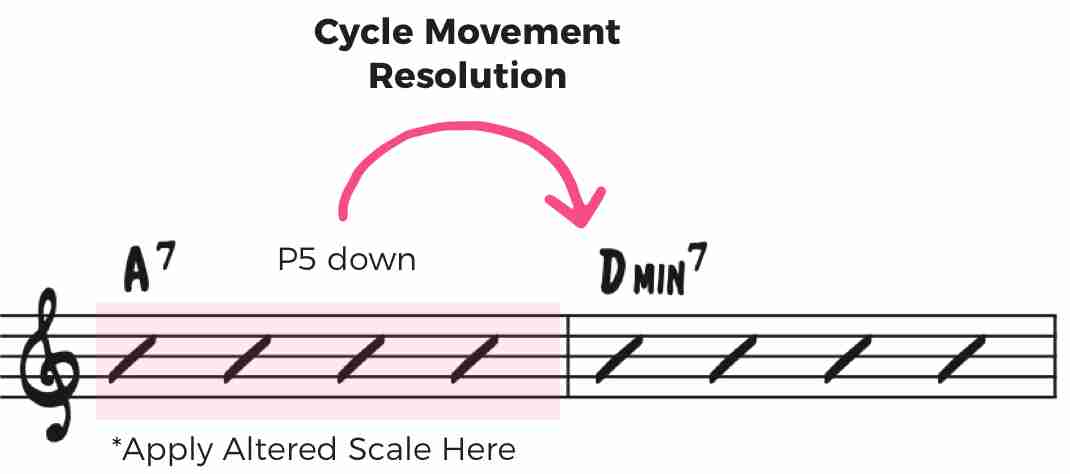

And in general, a strong resolution happens using Cycle Movement, so a good rule of thumb is that if a dominant chord moves to the next chord by a descending perfect 5th (or an ascending perfect 4th, same thing) then it’s a good bet that you can apply alterations to the dominant chord.

So for example, in the key of C major, if we encounter a G7, the V7 chord, and it’s resolving to C major, the Tonic, or a chord that’s acting as a substitute for the Tonic, then we might apply the Altered Scale to this G7 chord because it has a strong resolution, a descending perfect 5th (Cycle Movement) to the Tonic.

And the same logic would apply if we see a chord resolving to minor chord, like A7 moving to D minor because again, it’s resolving using Cycle Movement..

Now if a dominant chord does not have a strong resolution after it, then using alterations could end up confusing the chord sound you’re trying to convey within your melodic line.

So be aware of when you apply the Altered Scale, and be on the look out for a dominant chord resolving down a perfect 5th to really use it in the strongest way possible.

The Chord symbols for the Altered Scale

The actual chord symbols that specifically imply the use of the Altered Scale are pretty confusing, simply because chord symbols in a chart rarely reflect the exact chord voicing the pianist is playing…

But regardless, understanding the different dominant chord symbols that you might see in a chart and realizing that some of them do in fact imply the Altered sound is a good thing to know.

Technically, as you now know, the accurate chord symbol that would include every alteration that’s included in the scale would be: G7b9#9#11b13 because it contains all four alterations…

But that’s quite a mouthful…and a chord voicing usually won’t include all of these alterations.

So what you usually see notated in a chord chart is one of these:

- G7 Alt

- G7#9b13

- or maybe just G7b13 or G7#9

- And sometimes sharp is detonated with a ‘+‘ symbol instead: G7+9

I’m sure plenty of other variations exist…but the point is, you’ll rarely see all of the alterations written out because a chord is NOT a scale.

While the scale contains all four possible alterations, a piano chord voicing usually only includes one or two of them.

For instance, a chord voicing might have the root, the 3rd, the 7th, along with the #9 and b13 alterations, so in terms of the chord, they don’t need to write every possible alteration in the symbol because it doesn’t actually include all of them.

Where else can I use it?

Remember, the use of the Altered Scale is by no means limited to where a chart explicitly calls for it, and if you train your ear to hear all of the alterations really well, you can make it sound right almost anywhere.

Really, any dominant chord resolving using Cycle Movement, down a fifth (G7 to C major, A7 to D minor etc) you can use this sound over and be confident that it will work.

What about dominant chords with a Natural 13th?

The one thing that jazz educators like to warn you about is using the Alter Scale over a dominant chord that specifically calls for a natural 13th, as in the chord: G7b9Nat13.

If a chord has a natural 13th (E in the case of G7) included with altered 9ths, then using the b13th (Eb, D#) in your melodic lines, requires extra attention and melodic awareness within your line.

To say that it’s a rule, like many jazz educators say, that all G7#9b13 chords require the use of the Altered Scale, and that all G7b9Nat13 chords require the use of a different scale (The Diminished Scale), is a bit of an oversimplification.

The reality is, if the piano player is playing a G7b9Nat13 chord behind me, nothing says I have to precisely match their chord voicing.

I can still choose to alter the 13th in my my melodic line, as long as I can hear where it’s going and resolve the tension accordingly.

Melody is not the same as harmony! They’re intimately connected, but not the same. A chord symbol does not necessarily limit your melodic lines in the same way it would a chord voicing.

So be aware of this issue between these two different dominant sounds, what alterations they imply for the chord voicing, and how you choose to use alterations over each one within your melodic lines.

First Steps With The Altered Scale

When you’re first starting out with this scale, it can be pretty tricky. Here are a few tips to get you started…

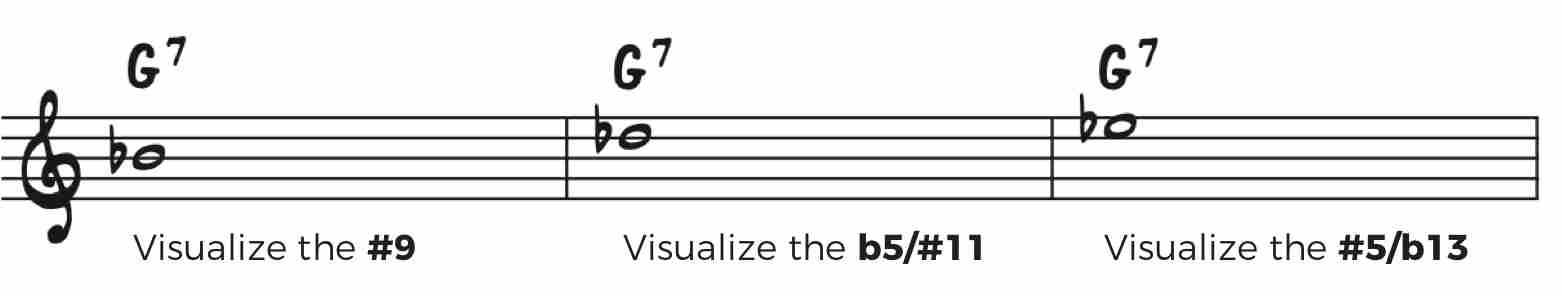

Step 1. Visualize each altered note

Arguably, even more important than knowing the scale is mentally knowing how each note in the scale relates to the chord without having to think.

For example, if I said, what’s the #5 of D7, could you immediately say A#/Bb. Or if I said, tell me the b9 of Ab, would you know it?

And could you go the opposite direction, for instance, if I said D# is the #11 of what dominant chord, would you know right away with zero mental effort?

Well, if this little quiz challenged you even in the slightest way, then it’s time to start visualizing. What do I mean by visualizing?

Visualization is the process of mentally seeing, hearing, & feeling information in your mind – It moves it to such a DEEP level, that you no longer require mental effort to access it.

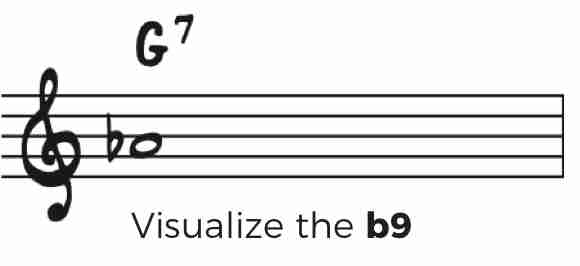

So first, practice visualizing the b9 on every V7 chord – see the chord symbol in your mind and imagine what it’s like to see, hear, and play the b9…

Then try visualizing the #9, then the b5/#11, followed by the #5/b13.

This skill is absolutely essential when using the Altered Scale, so if you’re serious about developing as an improviser, make sure to check out our detailed jazz course on Visualization For Jazz Improvisation.

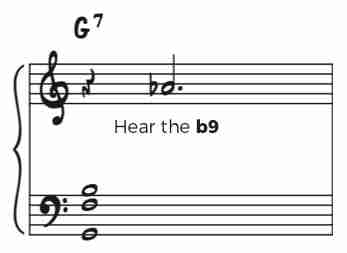

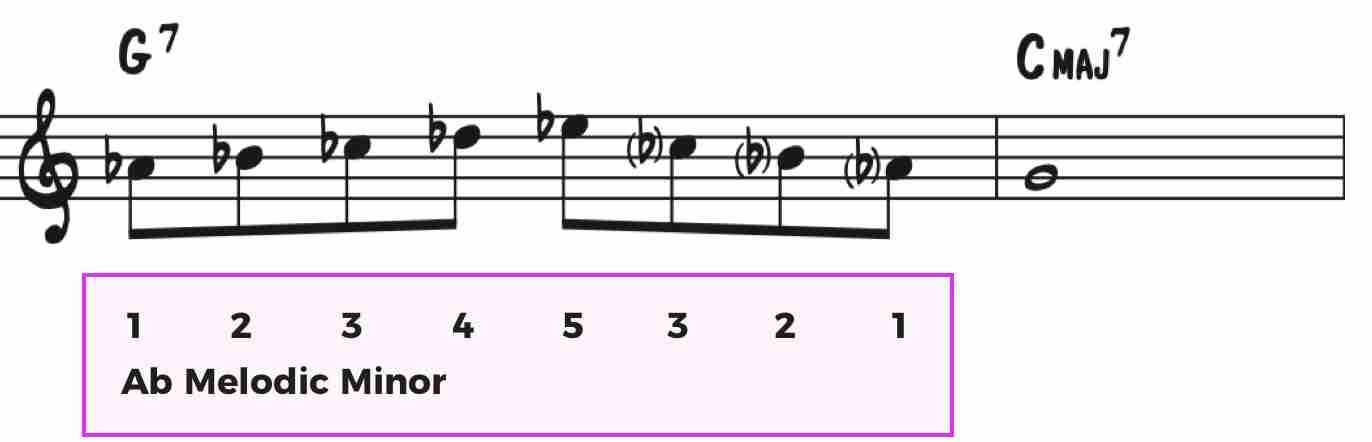

Step 2. Learn to hear the alterations

The second most important piece of wielding the Altered Scale is being able to actually hear how each altered note sounds against a V7 chord…

So for these exercises, you’ll use a keyboard and play the root, 3rd, and 7th of the dominant chord in your left hand, and then a single altered tone in your right, focusing on the sound of the altered chord-tone against the chord.

Starting with the b9 over G7, it would sound like this…

Then, once you work on the b9 in all keys, practice the same exercise with the #9, then the b5/#11, and the #5/b13.

Now if you want the fastest way to master these jazz chord sounds, it’s as easy as starting to train your ear with our Ear Training Method.

You can take this course everywhere, training your ear on-the-go and rapidly increasing your aural awareness every single day.

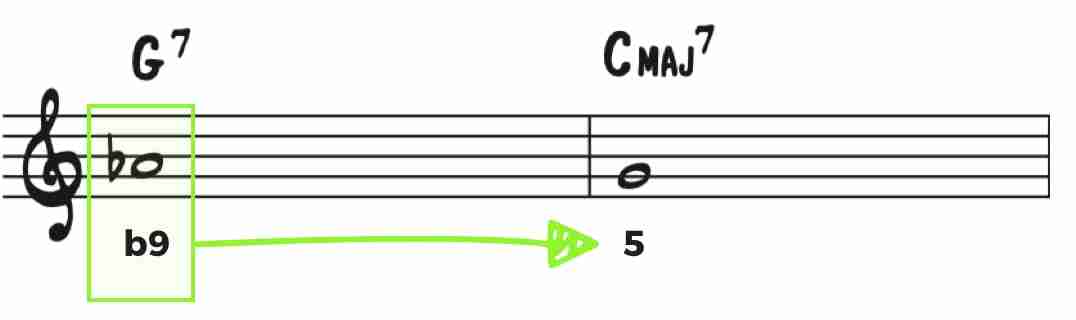

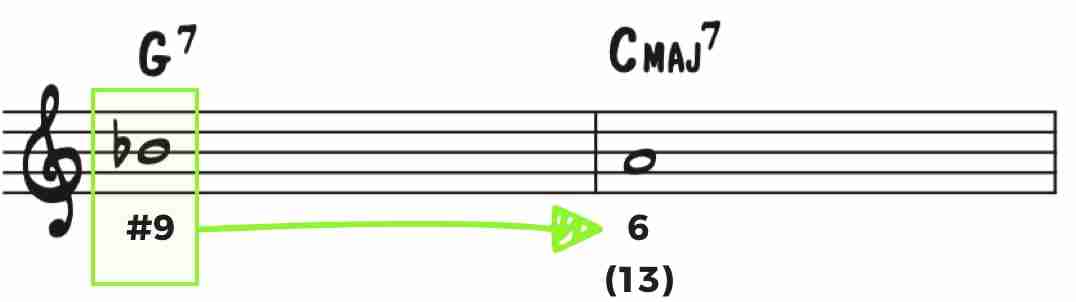

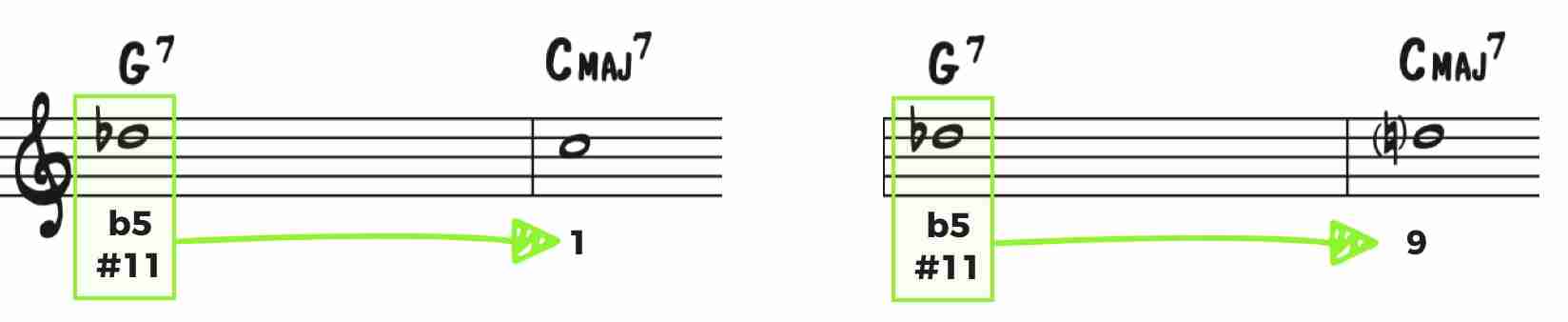

Step 3. Understand The Resolutions

Lastly, a vital part of using the Altered Scale comes down to having a clear idea how every altered tone in the scale resolves because without resolving the tension clearly, the altered notes can end up sounding out of place or just plain wrong.

Now, to say every altered tone resolves in a single way is just not true. Does each tone tend to resolve a specific way?

Yes, but this doesn’t mean that it can’t resolve another way…

So use these resolutions as a starting point, but explore other ways of how you might strongly resolve these tensions.

The b9 (Ab on G7) generally resolves strongly down to the 5th of the Tonic chord, (G on C major).

The #9 (technically A#, but shown here as Bb) can resolve down to ‘A’, the 6th or 13th of C major.

The b5/#11 (C#/Db) resolves both down to the root of the Tonic and up a half-step to the 9th.

The #5/b13 resolves both strongly up to the 3rd of the Tonic and down a half-step to the 9th.

There is a lot of information packed in here, so take your time understanding these resolutions of altered chord tones and practice hearing them.

Remember, there are only four altered tensions present in the altered scale and people frequently call them by different names, which can be a little confusing.

So, get familiar with each of these tensions, the different ways they can be thought about in terms of the chord structure, and how each one resolves.

Things to watch out for with the Altered Scale

Just like any musical device, there are always things to watch out for.

Now we’ve talked a little bit about these important points already, but they’re so crucial that we’re going to go a little deeper into them for a minute…

Get beyond The Shortcut

When I was 18, I attended Jamey Aebersold’s jazz camp in Louisville, Kentucky, and had a blast! Playing with great musicians, learning from pros, I truly enjoyed every minute. But one discussion sticks out in my mind when it comes to the Altered Scale…

One afternoon, the great saxophonist and educator Jerry Coker told our ensemble that he and Jamey thought about the Altered Scale slightly differently…

Jamey felt that it was no big deal to think of the scale as a mode of the melodic minor, but Jerry had a slightly different opinion, saying that knowing the scale as its ‘own thing’ was absolutely necessary to use it effectively.

Jerry stressed that knowing the scale independently from the melodic minor scale would allow improvisers access to the scale more quickly and therefore, give them the ability to use it more easily.

And I really like Jerry’s notion here…

You eventually want to be able to think of The Altered Scale as its own entity

Using the melodic minor scale to derive the Altered Scale is a fine shortcut for starting out, but it’s necessary to get beyond this shortcut, and have the scale under your fingers and in your mind without having to think of its parent melodic minor key or scale.

Avoid runing up and down the scale aimlessly

This sounds so obvious, but it’s one of the biggest mistakes beginners fall into…

Learning a new complex scale, you might incorrectly assume that it’s the mere use of the scale that makes your lines sound good, so you start to run up and down it, thinking that your goal as a soloist is accomplished.

Running up and down a scale aimlessly is not music, and it’s certainly not jazz improvisation

Instead, you want to acquire altered dominant language and understand how the Altered Scale fits in with the language you’re learning. Use these lessons to acquire useful altered dominant language techniques in your playing:

- How To Play V7 To I Like A Pro: 5 Techniques From The Masters

- 10 Easy Options For Expanding Your Dominant 7th Vocabulary

- 5 Steps To Becoming A Lyrical Master With Altered Dominants

Develop a relationship with EACH alteration

This might sound a little strange, but when you think of any alteration over any V7 chord, you want it to be like a seeing an old friend…

So when you go to think of the b9 of G7, it’s like remembering one of your close friend’s names. You don’t have to think of their name, or their face, or their demeanor…your brain already has the overall impression of all this.

Your friend doesn’t have to introduce themself on the phone, you recognize their voice immediately, without any thought.

This ‘friendship’ is the type of relationship you want with with each altered chord-tone.

Without it, the Altered Scale is just a collection of unfamiliar sounds and concepts…but with it, the scale becomes alive.

Altered Scale Techniques & Exercises

Okay, now that you have a pretty deep understanding of this scale, let’s dive into a few jazz practice exercises for the Altered Scale…

Practice Scalar segments

When you first start to use the Altered Scale in your solos, you may still have to think of the related melodic minor. This is not a bad thing, but remember it’s a shortcut – and it this shortcut takes mental processing time.

But when you’re first starting out, scalar segments can be a good way to familiarize yourself with the scale.

For this exercise, use the digital pattern 12345321 of the parent Melodic Minor, so over G7, use 12345321 of Ab Melodic Minor, and resolve the pattern to the 5th of the Tonic (G in the key of C major).

As you play the digital pattern, try to mentally connect your use of Ab Melodic Minor with G7alt.

Eventually, you’ll no longer need to consciously think about this relationship and your brain, fingers, and ear will just know it intuitively.

Practice highlighting a few notes

Whenever you begin to work on a new scale, the tendency is to try to use the whole thing – in this case, all 7 notes.

But it’s much more effective when you learn to use small pieces, or even 1 or 2 notes from the scale in a melodic way.

Listen to Sonny Rollins here over Tenor Madness…

He frequently uses the b9 and #9 together over dominant chords as he does here (2:39)…

This is such an easy yet effective melodic technique. Simply learn to use the b9 and #9 from the Altered Scale over a dominant chord in a musical way.

You can work on other altered notes, combinations of altered notes, or scale fragments using the same kind of idea, highlighting only a couple notes from the Altered Scale rather than feeling like you need to use the whole thing all the time.

Use chromatic passing tones

Another great technique that I remember great tenor saxophonist Eric Alexander talking about is the technique of inserting chromatic passing tones into the Altered Scale, essentially creating Altered Bebop Scales.

By adding chromatic passing tones in between altered notes, you can emphasize specific altered tensions within the scale.

For example, this is the Altered Scale with a passing tone in between the root and dominant seventh, similar to the bebop dominant scale. It puts 1, the dominant 7th, #11, and #9 on the strong downbeats.

Or, perhaps you insert a passing tone in between the b13 and #11, which puts 1, b13, #11, and #9 on the downbeats:

You can create all sorts of Altered Bebop Scales like this just by experimenting a little bit. Play with this idea and see what you come up with!

Incorporating The Altered Scale Into Your Playing

Working the Altered Scale into your playing in a musical way takes some time…

Here’s an idea of what it might look like by taking all the information we talked about today and putting it into a practice plan…

10 Steps to Integrating The Altered Scale Into Your Solos:

- Understand the structure of a G7 chord all the way up to the 13th

- Understand the Altered Scale Shortcut & Practice Ab Melodic Minor

- Use the Altered Scale Shortcut to start playing G7alt. In other words, play Ab Melodic Minor from G to G

- Visualize each altered tension over G7

- Practice hearing each altered tension over G7

- Next, play 12345321 of Ab melodic minor over G7alt, then work on some variations of this digital pattern

- Begin to feel and hear the G Altered Scale as it’s own entity, getting beyond the Altered Scale Shortcut

- Start to highlight specific altered notes over dominant chords, while understanding each resolution

- Start using Altered Bebop Scales by inserting half steps in various places

- Freely, confidently, and musically begin to apply the Altered Scale to dominant chords in the tunes you are working on

This is no easy feat!!

With this plan, you’ll gradually transcend the Altered Scale, automatically knowing the altered sounds you wish to emphasize and how to best use them within your improvised lines.

Listen to your heroes and strive to figure out how they’re making use of these concepts and emulate them.

In time, you’ll be a master with the Altered Scale!!