Doxy is one of those classic Sonny Rollins tunes that gradually made its way into the jazz standard repertoire. Originally recorded in 1954 and released on the album Miles Davis with Sonny Rollins, its compact form and changes make for a great improvisational vehicle.

And today, Doxy has become one of the most recommended tunes for beginners and something you hear many people play at jam sessions, and for good reason…

It sounds simple…

Many years ago when I first heard Doxy as a beginner, I instantly was drawn to the tune and it sounded quite easy, so I decided to pursue it…

Unaware of the great benefit of transcribing and learning from recordings at the time, I purchased a play-along set, put the background track on, and opened the book to the chart of the tune.

To my surprise, Doxy didn’t look so simple…

A mix of dominant chords and advanced scales written out under the changes, the chart from the play-along didn’t look nearly as easy as it sounded…

So what did I encounter here and what’s going on?

Why do countless charts of tunes that sound so easy, look so complex? And what can you do to remedy this problem and distill your understanding of these tunes into the simple elements that they actually are?

Today, we’re going to show you why charts to “easy” tunes are completely messing you up and how to fix this.

In the process, we’ll get into:

- What transcribing the melody can teach you

- Why transcribing bass lines is so important

- How a transcribed chorus reveals how a soloist thinks

- All the little details of Doxy

- The approach Miles Davis uses on Doxy

And a whole lot more…let’s get started…

The Problem With Modern Day Charts

A chart is a compromise of what someone thinks a recording contains

Most people look at a jazz chart or lead sheet as the official chords to a tune, but the reality is, many charts have numerous issues.

Here are three of the primary issues with charts that lead aspiring improvisers down the wrong path…

1. Wrong changes & mistakes

The first issue is the most obvious one…

A chord is notated wrong. A bass line is transcribed incorrectly. Or a melody note somehow got entered a step off…

This is common and in their defense, many recordings are of poor quality, which can make it very difficult to hear the comping chord changes from the piano, or the bass line from the bassist during a solo.

Even if the recording isn’t of poor quality, with all the instruments going on at once, it can be very difficult to pick out the exact notes a player is playing, and ultimately the transcriber just has to make a choice.

So it’s not necessarily their fault, but it’s still very common that a chart simply entered in the wrong information and there’s no way you’d know it unless you transcribed it yourself.

2. Different versions & Interpretations

Another issue with charts today is that there are many different versions of a tune to choose from because at thins point, the song has been recorded dozens of times, by dozens of musicians.

So which version s correct? The original? The most popular? The most recent?

Even the original composer may play their tune slightly different from performance to performance. But the reality is, there’s no single “right” answer. Just many different interpretations.

And this brings us to the next issue…

3. Many decisions boiled down to a single set of changes

When someone creates a chart, they have to make quite a few decisions as to what they notate in the chart because jazz is so dynamic.

The band might play different chord changes during the melody than during solos. Or, the bassist might switch up their bass line from chorus to chorus…

Or the pianist may sometimes comp using an unaltered dominant chord at one point and then later play an altered dominant chord. I’ve even transcribed tunes where it’s clear the bass and piano seem to be thinking of different changes.

And these are just a few of the things that come to mind! There are countless others, but the point is: a chart can’t possibly contain all the variations played by the band, so they must choose one to notate.

Unfortunately, modern day charts usually make decisions that add more complexity…in doing so, they lose the essence of the tune and the essential story of the tune is no longer communicated by looking at the chart.

Instead of understanding the important transition points and key moments and destinations in the tune, the chart viewer ends up being bogged down with extra chords and scales.

So what happens when you start with a chart?

When a chart is your entry point into understanding a song, it’s as if you’re trying to build a house by starting with the roof.

Rather than starting with the foundation, you’re jumping to a much later point in the process that relies on the things you skipped over…

Starting with a chart to Doxy

So let’s take a look at what it might look like to begin with a chart of Doxy, for example, take the chart that I received with the popular play along set…

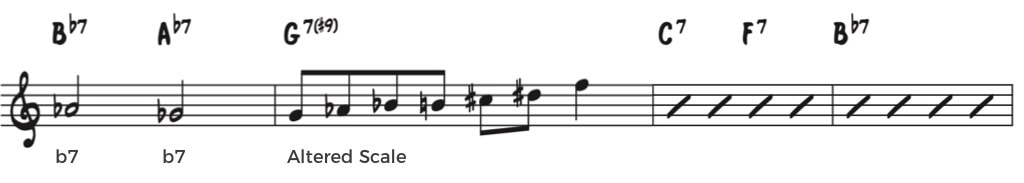

And now, imagine you were to create a solo with these changes in mind…

If you’re anything like me when I was learning how to play, you’d try your best to hit all these changes by emphasizing the key notes that the chart tells you are important, especially the “cool” notes: the 7, 9, 11, 13, or altered notes.

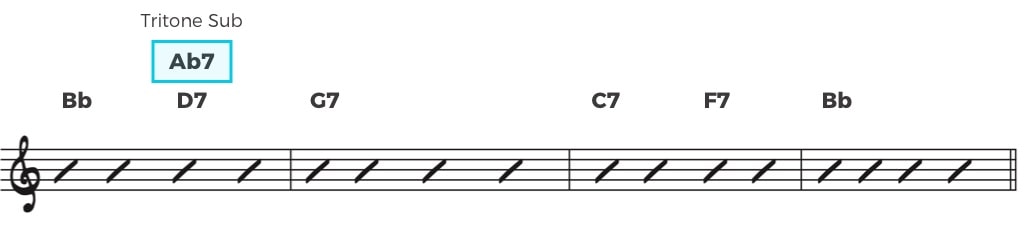

So over the first few bars of the first A section, you might hit the b7 on the first chord Bb7, the Gb on the second chord Ab7, and then perhaps run up the altered scale on the next chord G7+9, this would be your line of thinking…

And you’d assume that you were doing everything correctly, after all, you’re following the changes that you were given…

But is this how a jazz legend approaches this tune? Is this their line of thinking? Or are they thinking completely different from you?

Spoiler Alert: Greats like Sonny Rollins or Miles Davis are thinking differently about the changes than you because they’re not coming at them from a modern day chart.

In most cases, these great musicians either…

- Wrote the tune themselves

- Had the original chart from the original composer

- Talked with the original composer

- And/Or transcribed the tune for themselves

So the only way for us modern day players to get on their level is to spend time with the recording of a tune and use all the information on it to develop our understanding.

Only then will a chart actually make sense to us and not send us in the wrong direction…

How to Use a Recording To Shape Your Understanding

So you know that have to have a solid foundation and everything else in place before you get to the roof. But how do you do it?

Start by acquiring some basic transcribing supplies…

Then, get to work…transcribe things like:

- The melody of the tune

- Part of the bass line or piano chords during the head

- Part of the piano comping or bass line during a solo

- A line or chorus of your favorite solo

When you transcribe this information for yourself, you’ll be able to identify all the decisions and inaccuracies that you later encounter in a chart, if you choose to use one at all.

And then, instead of these decisions and inaccuracies within a chart dictating what you play, you’ll be in control.

So now we’re going to walk you through this process, starting with the melody and seeing what it can tell us about the tune…

The Doxy Melody

Have a listen to the Doxy melody…

Right away, one of the first things that you can start to acquire from transcribing a melody for yourself is a sense of the Form.

And by working with the melody and hearing it many times over and over, you’re ingraining this crucial element in your brain.

Now besides the form, when you transcribe the melody for yourself, you’ll get all the little details that many charts either completely miss, get wrong, or leave out…

For example, Sonny and Miles play each A Section in a slightly different way each time, which many charts do not notate…

If you listen closely, you can hear these details…

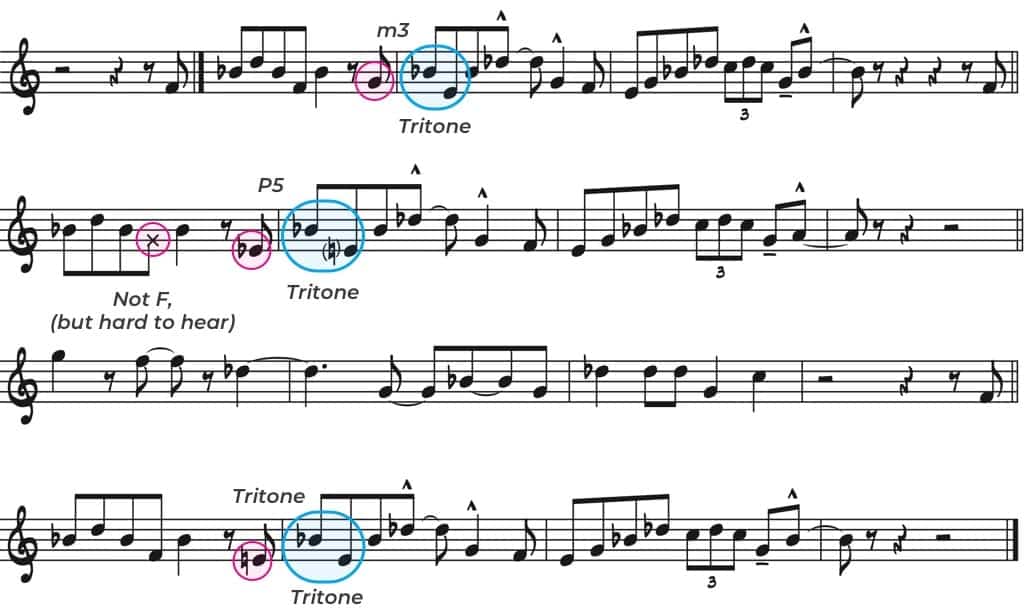

- The pick up note into the second bar of each A Section is different each time. You can hear the intervals vary: a minor 3rd the first time, a perfect 5th the second, and a tritone the last

- The first bar is an inverted Bb triad, except in the 2nd A it sounds more like a G instead of an F

- The first two notes of the second bar of each A Section form a tritone

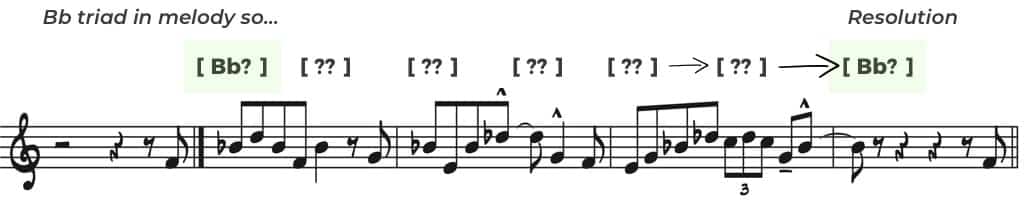

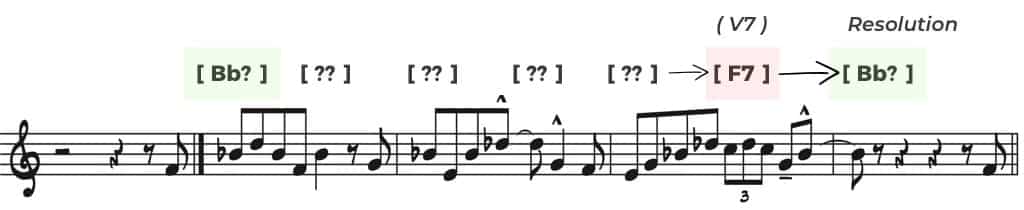

And lastly, when you transcribe the melody for yourself, you start to create a sense of The chord changes without even studying the other instruments.

For example, just by looking, you can probably guess that the A Section starts on some sort of a Bb chord (we don’t know the quality of the chord yet) and hear that it resolves back to Bb in bar 4.

From there, if you understand jazz theory on a deep level, you can make some educated guesses based upon chord logic and what you hear to fill in some of the other chords.

So what chord typically moves to Bb?

Of course F7, the V7 chord moves to Bb so it will likely be right before the Bb in bar 4.

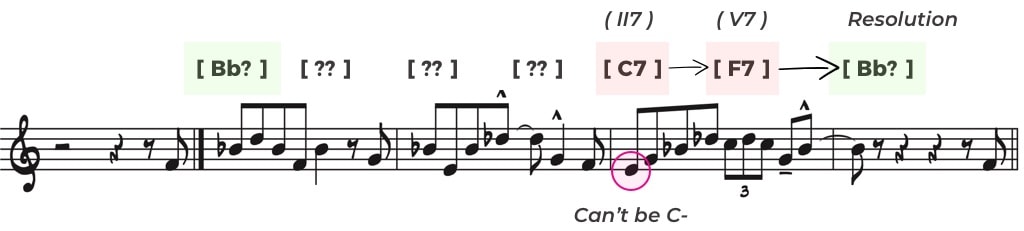

And prior to the V7 chord is usually the ii chord, but because you can see an E natural in the melody, there’s no way it can be C minor so you might predict that it’s C7 instead, the II7 chord…

And you don’t have to figure out everything at once. While you could keep applying your chord logic here, simply take the information you discover and start to put it together as best you can.

With each new piece information you transcribe or hear, the more a tune will be revealed to you.

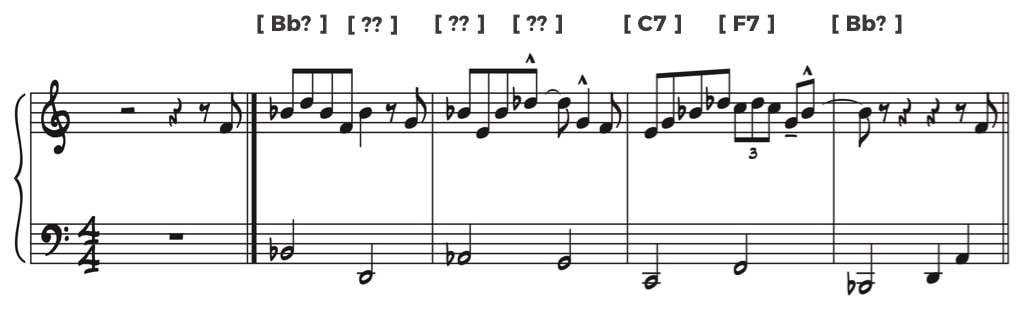

Adding in the Bass Line & Piano

While not nearly as popular as transcribing a melody of a tune or a solo, transcribing the bass line is hugely beneficial.

Keep in mind that bass lines frequently use approach notes, so not every note will be the root note of a chord, but that most of the notes on the strong downbeats (1-2-3-4) will be the root or 5th of the chord.

And if they’re not the root or 5th of a chord, they’re usually another chord tone, like the 3rd or 7th.

This is not always the case, and you have to constantly use your ear to determine this, but it is a good rule of thumb.

Getting the bass line

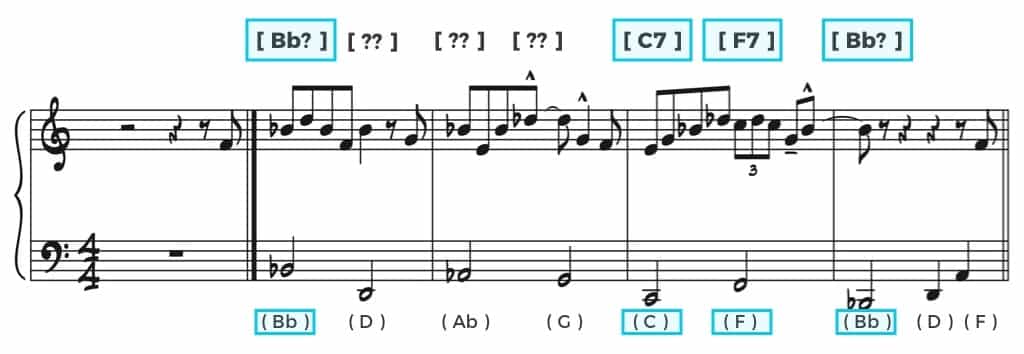

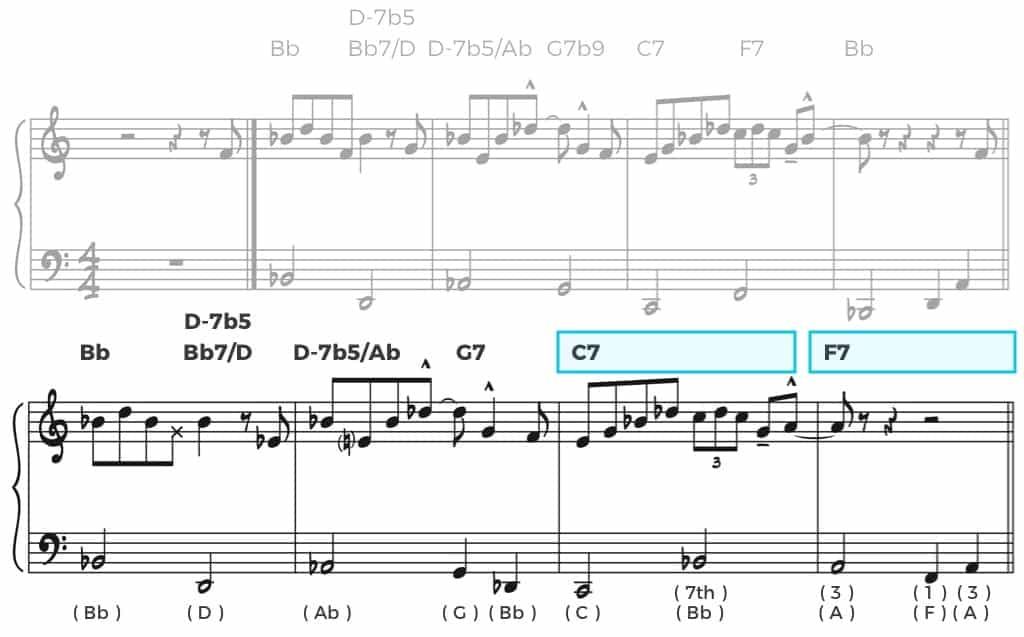

For starters, take a look at the bass line with the melody during the first 4 bars…

See how the roots of the chords we predicted from the melody actually match the bass notes?

This is a great confirmation that we’re on the right track…And in terms bass lines, always ask yourself…

- Is the note in the bass the root note of the chord?

- If it’s not the root, is it another chord tone like the 3rd, 5th, or 7th?

- Or is it an altered note or passing tone to the next note?

And then after getting the bass line, listen to the piano to determine the quality of each chord (whether it’s major, minor, dominant, etc…)

Getting the quality of the chords

This is where your jazz ear training is paramount…

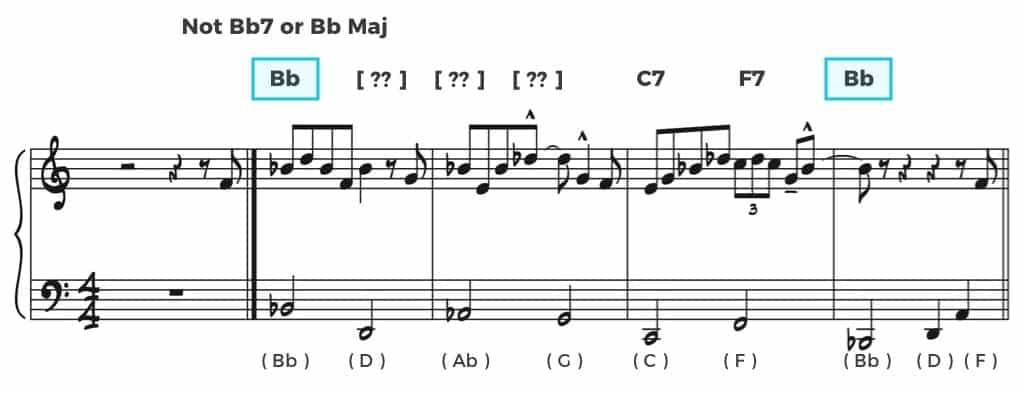

There are quite a few spots that you can hear the quality of the first chord is not dominant or major 7, but sounds more like a Bb triad or Bb6. This is during the first A when Miles is soloing…

And this is at the start of second A during his solo, slowed down a ton so you can hear the Bb6 quality and absence of anything that resembles dominant…

And this goes for the quality of the Bb chord in bar 4 as well, our resolution point. It’s NOT dominant, it’s just a Bb triad or perhaps the pianist may include the 6th.

So I’d notate it just as Bb or Bb6 (We’ll keep it simple and label it Bb throughout even though I hear a 6th in the voicing often).

This is a small detail, but one that dramatically affects the character of the tune and one you’d never know if you didn’t transcribe the melody for yourself.

Now onto the latter part of the first bar, you can hear that the next chord emphasize a D and an Ab.

So you can hear this, I’ll play the first two A Sections from the recording, and on top I’ll play a D and Ab right after the chord in question…

Hear how the notes I’m playing, D and Ab mirror the sound of the second chord?

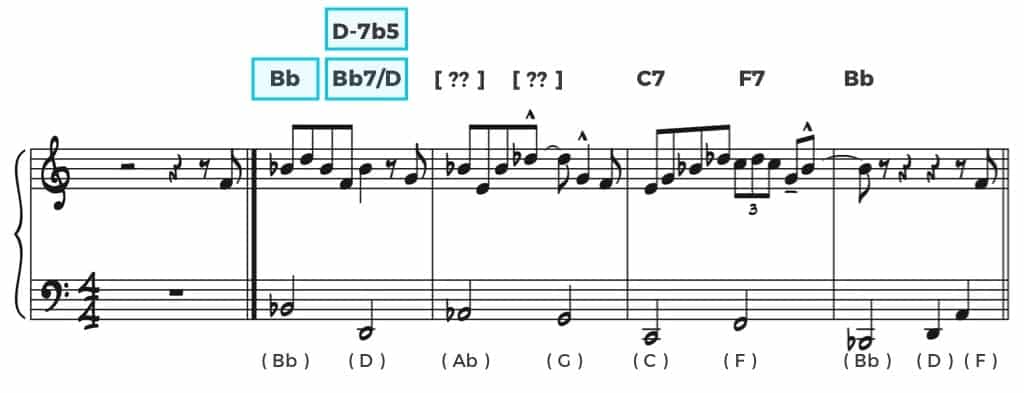

With a D in the bass, it can be heard as a Bb7 dominant chord over D (the 3rd), but because the bass note is D, you also might hear the chord as a D half diminished chord so I’ll write both in there…

And the next two chords…same thing. You have to use your ears, listen to what the piano is playing and make sense of it with the bass line.

By combining your ears with the logic of how chords move, you can slowly figure out what’s going on…let’s keep going for a minute…

Figuring out the rest of the tune

Listening closely to the piano and bass line in the Second A in bar 3, you can hear that the C7 chord is held out for the full bar and that the melody note in the 4th bar, A, sounds like the 3rd of a dominant chord, so it has to be F7.

Are you starting to realize why transcribing the bass line helps you so much?

Throughout this process, I haven’t written out a single piano voicing! I’ve only listened for the quality of the chords the piano is playing, which is a whole lot easier than writing out a complete chord voicing…

Instead, I focused on writing out the bass line which then gives me the structure I need to understand the changes.

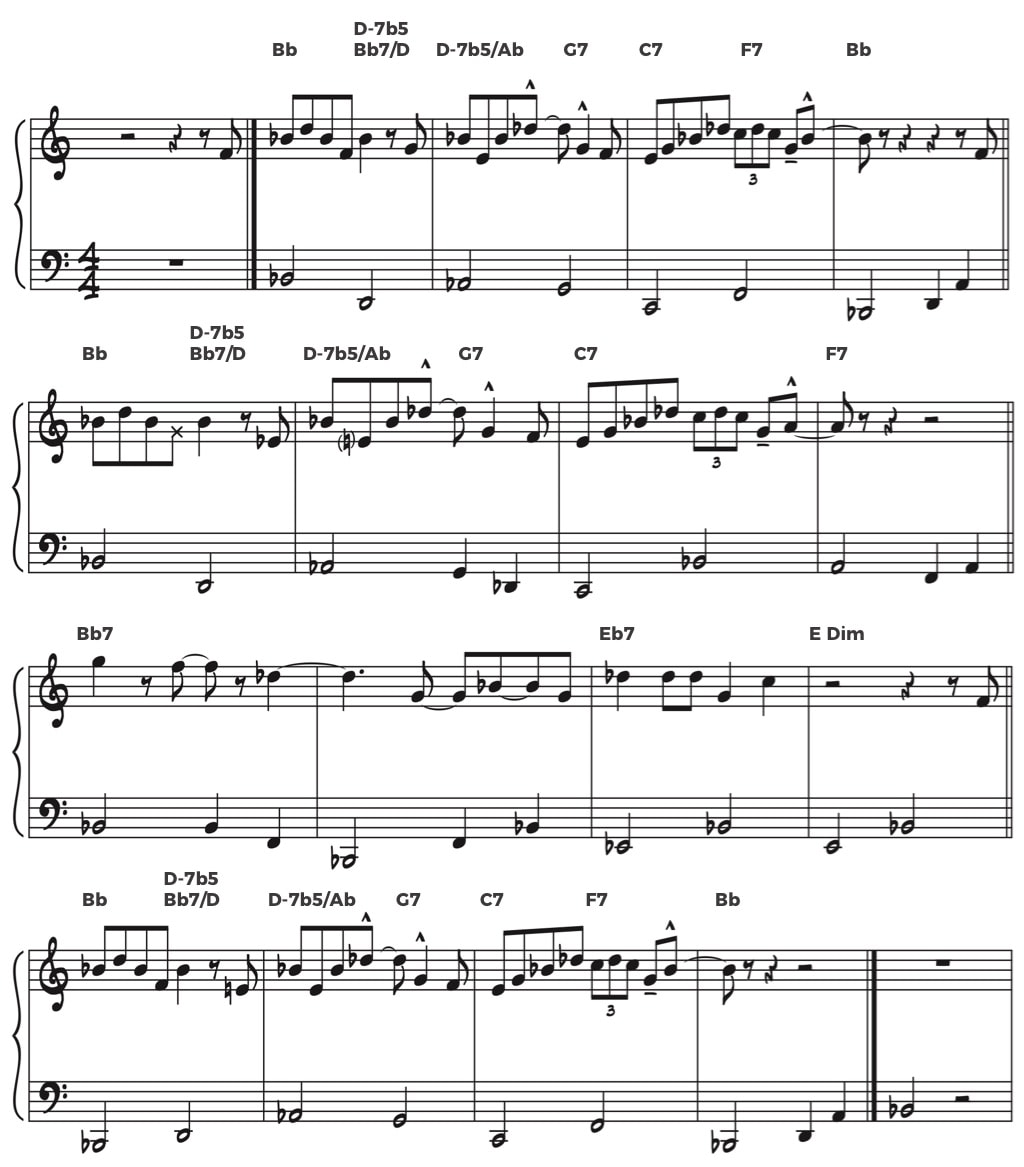

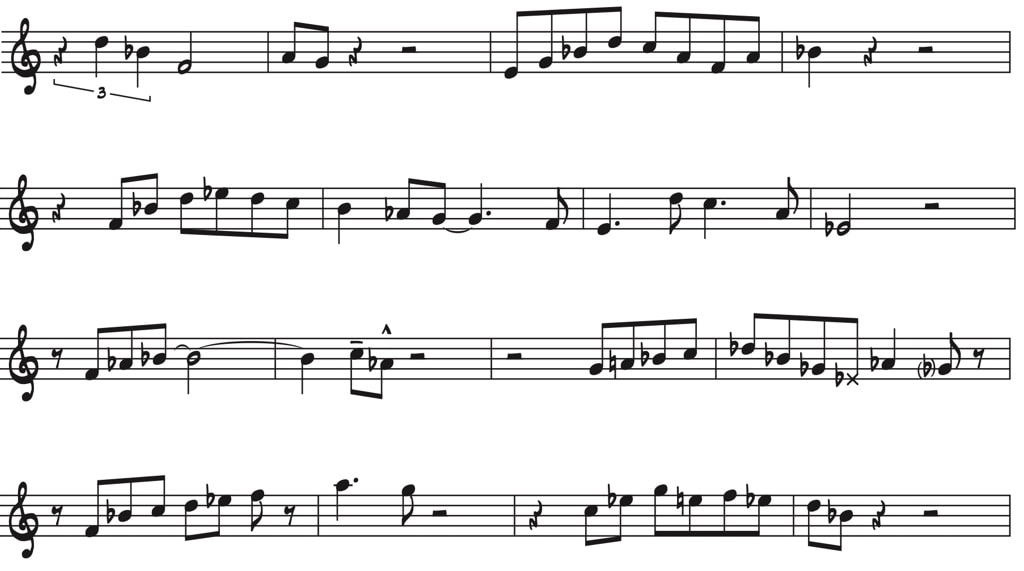

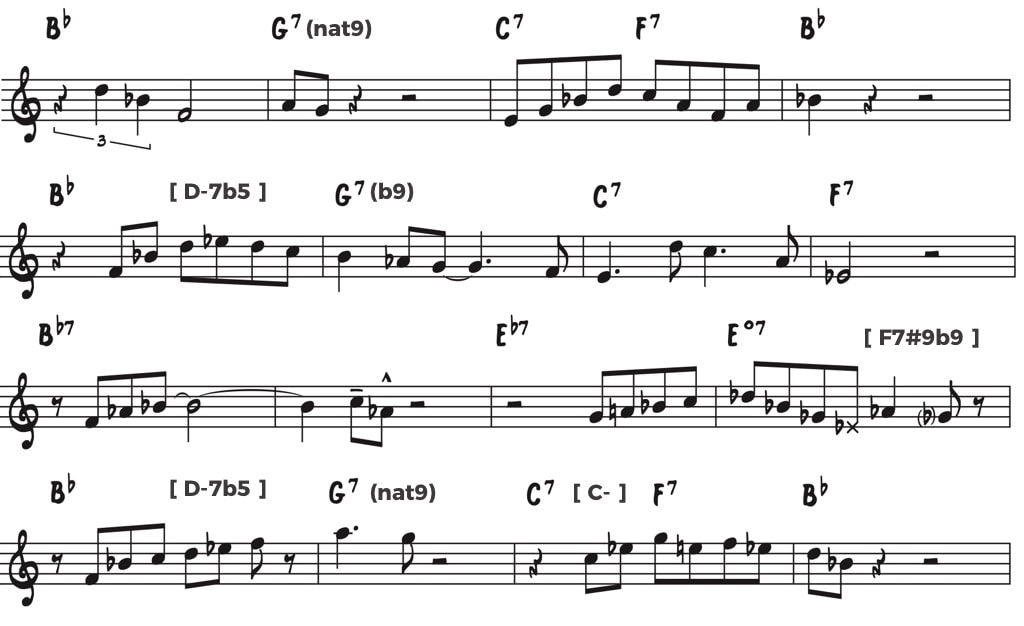

Continuing with the rest of the tune, we’d arrive at a full chart of our own interpretation, something like this…

Keep in mind that this is by no means the so-called perfect chart to Doxy and I’m not trying to present it as such.

It’s simply the way I hear how the tune is put together during the head (which may be different than the changes during solos as you’ll see in a moment) when I transcribe and interpret the information for myself.

It’s the process that matters and it’s the work you put into the process that will help you to develop your understanding of a tune.

Use what I’ve done here today as a demonstration of the process, adapting it and integrating it into your own practice.

What about the changes during solos?

One thing that might trip you up when you’re trying to get changes from a recording is that the band may play slightly different chord changes during the solos then they did during the head…

This is super common so it’s something to watch out for.

And on top of that, the band may even switch up how they play the changes from chorus to chorus, or from solo to solo.

With chord changes, there’s no one-size-fits-all!!

A chart could take any of these variations and declare them the changes, but as you transcribe a solo for yourself and get deeper and deeper into it, you’ll understand the crucial parts that create the essential structure of the tune, versus the places where the band takes a bit more liberty.

So to find these places, simply listen to the changes during the solo and pick out the spots that you hear as different from what you’ve already transcribed.

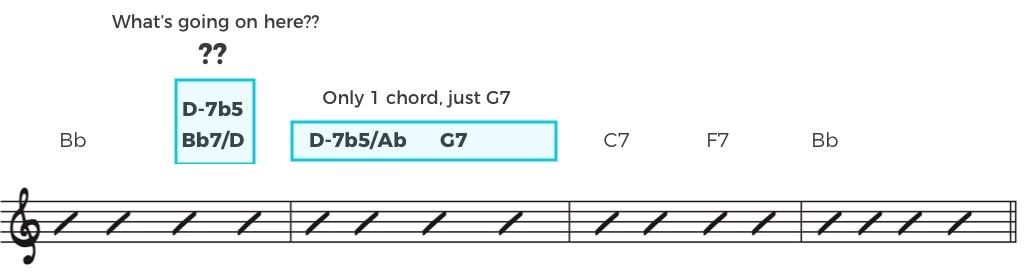

For the most part, it sounds like the changes are the same, but listening ever so closely, the first few bars of the A Section sound a little different during the solos than they do in the head.

- The second chord on beat 3, doesn’t sound quite the same

- In the second bar, it sounds like there is only one chord, a single dominant chord, instead of two chords

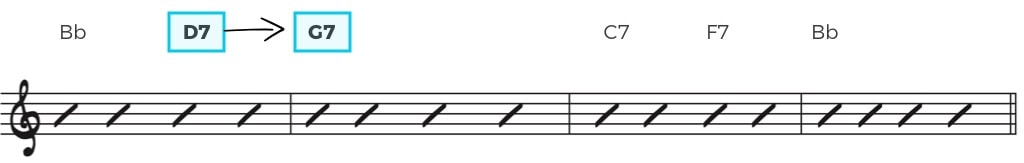

And on top of that, you might remember that the popular chart from the play along set that we talked about earlier showed an Ab7 chord on beat 3 of the first measure…

So this is something we need to investigate as well…

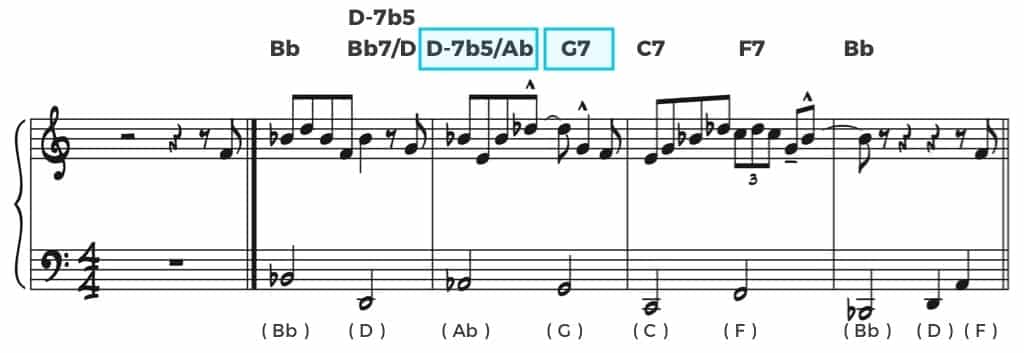

During the head, we called this chord a Bb7 or D half diminished chord, but if you listen closely at this spot during a solo, it sounds like the pianist is emphasizing the notes C and F#, and that when Miles plays an F on top, it sounds like a sharp 9 of a dominant chord.

Have a listen to it slowed down…

So on top of a D bass note, F# would be the 3rd of a dominant chord and C would be the 7th, while the note miles played, F, would be the #9. So the chord with Miles playing over it would end up sounding like a D7#9.

Now listen as I alternate between the recording and playing a D7#9 chord on the piano…

Could it be possible that a D7 dominant chord works here too?

Of course!

D7, like D half diminished, moves to G7, so the chord logic remains. And because during the solo the entire measure of bar 2 is G7, it actually makes perfect sense that the chord right before it drives even more to it.

And what about this Ab7 chord that almost every chart shows?

Well, coming from the knowledge of D7, it’s simply a tritone sub and something you hear the rhythm section actually start to do during Sonny Rollins solo during the First A…

And perhaps even more clearly during the Second A…

So by studying the recording for yourself, you can make sense of the changes within a chart and understand all the decisions they made to put it together.

You can then go through the chart and revaluate it for yourself…

And when you discover the changes for yourself, you’ll notice a whole lot of options at your disposal…

That’s why it’s so difficult to create a perfect chart and why chart-thinking limits you so much – it’s like putting a straight jacket on when you have the comfiest pair of sweats sitting right in front of you.

With “Chart-Thinking” you’ll constantly miss all the opportunity and understanding as to why many variations work in a particular spot.

Keep in mind though that with any of these spots, there is still an underlying chord logic and sound that makes things work.

Unless your Michael Brecker you can’t play anything you want, but you can play many things if you understand the sounds on a deep level.

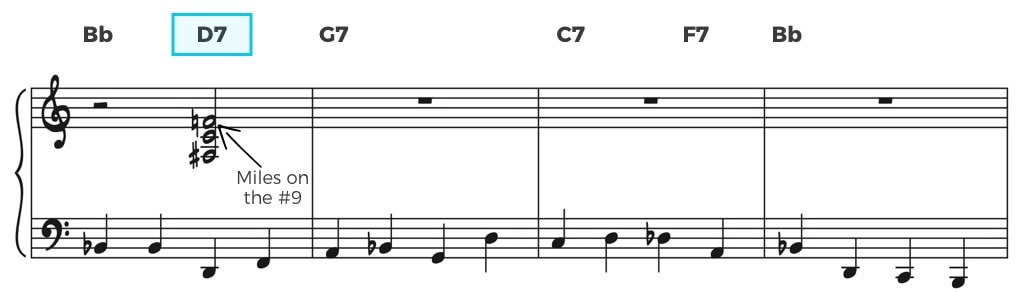

How Miles Davis Thinks on his Doxy Solo

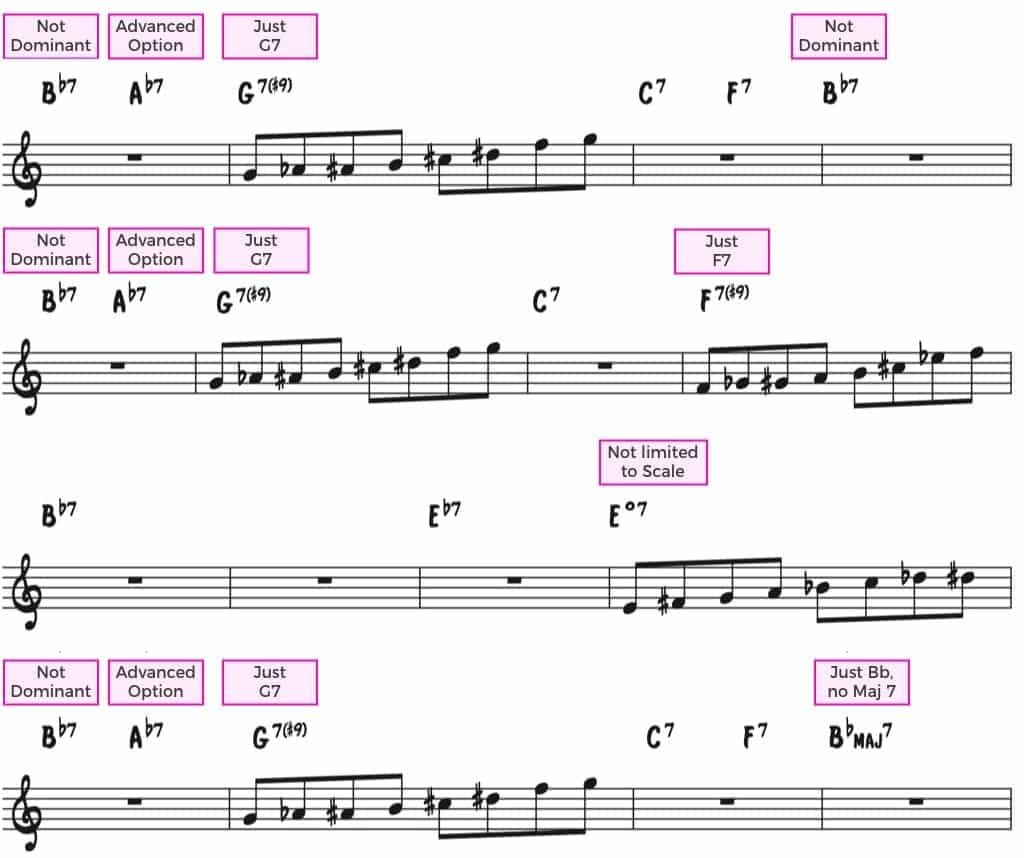

Now that we’ve transcribed the melody and the bass line, and gone deep into the quality of the chords by listening to the piano, let’s add in one final piece of information…a chorus of Miles Davis playing a solo on Doxy.

Take a listen to this beautiful solo…

Okay, let’s take this section by section with the purpose of understanding what changes Miles is thinking about and how these compare to both the chord changes we’ve transcribed and the typical chart changes.

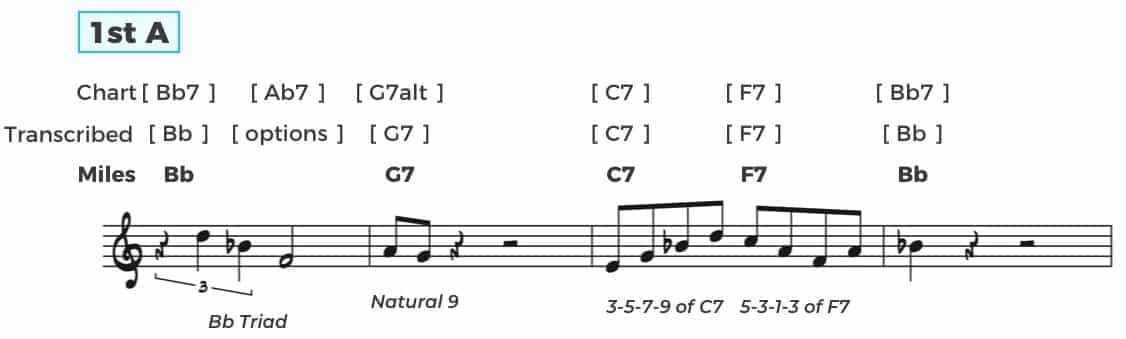

The First A Section

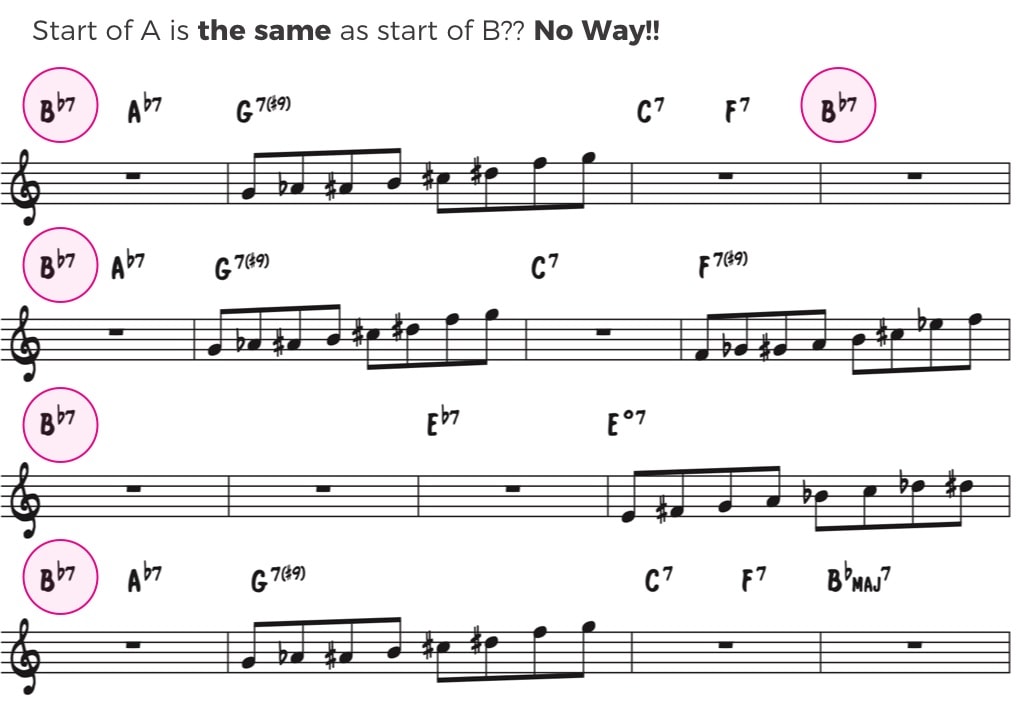

Have a listen to Miles first line and see if you can hear and see how he’s thinking about the changes…

In the first four bars, Miles is clearly not thinking of Bb7, Ab7, D7, or G7+9. Instead, he’s playing a simple Bb triad over the entire first measure…followed by a normal unaltered G7 chord, emphasizing the natural 9, A natural.

As you can see, if you were using the chart and hadn’t figured out anything for yourself, you’d be starting with a Bb7 dominant sound, inserting an Ab7 on beat 3, and altering the G7 chord.

Remember, none of this is wrong, but it’s a much more complicated way to get though the changes. Might you sometimes think of these more complex changes?

Sure, you might insert an Ab7 on beat three, or alter the G7 chord, but they’re not the changes that you should start out with.

And they’re not what you should think of as the core changes…

Aim to start with the most basic set of chord changes and then slowly add in more advanced options as you progress.

Often times, as you can see here with Miles, you may prefer the basic versions as you solo, and leave some of the variations to the rhythm section.

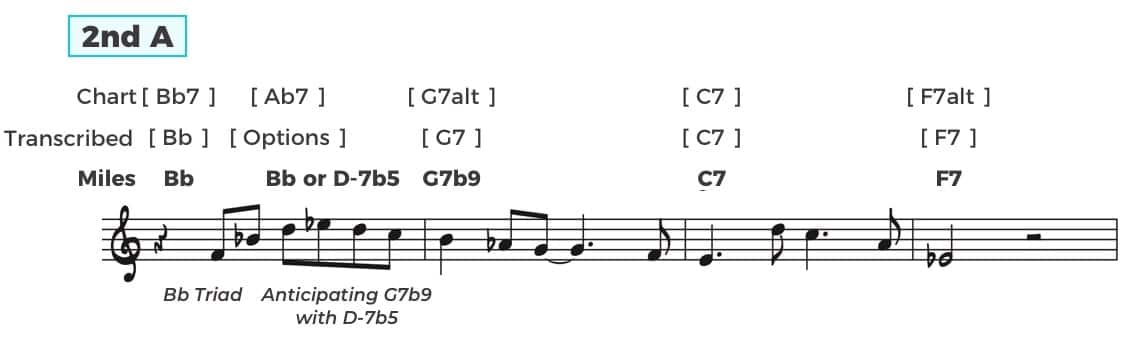

The Second A Section

Now listen to Miles play over the Second A…

As in the First A, Miles again use a Bb triad in the first measure, however it seems as though he may be using the variation of the changes we discovered during the head, the D half diminished chord on measure 3.

This sound anticipates the G7 chord in bar 2 which Miles chooses to use a b9 on here…

Again, from studying the recording, you’ll be able to create lines through the changes much more easily because you won’t be trying to fit your playing into some arbitrary box that the chart has bestowed upon you.

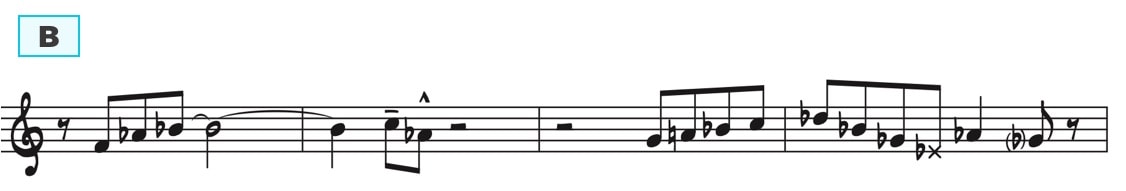

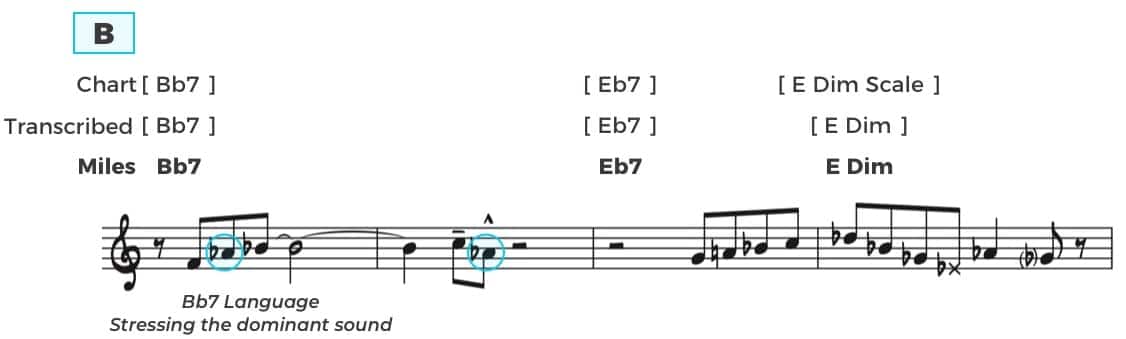

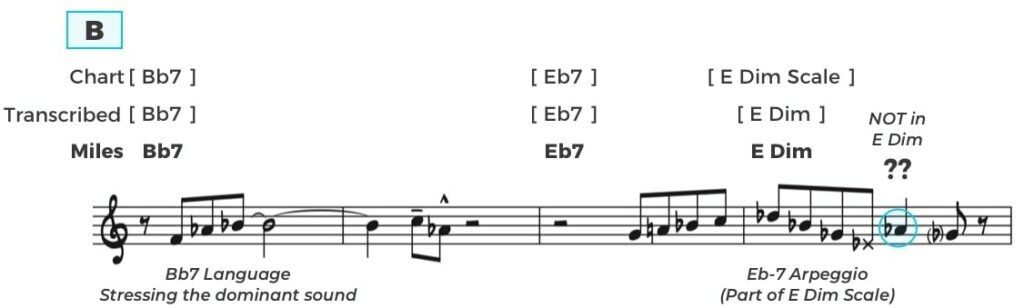

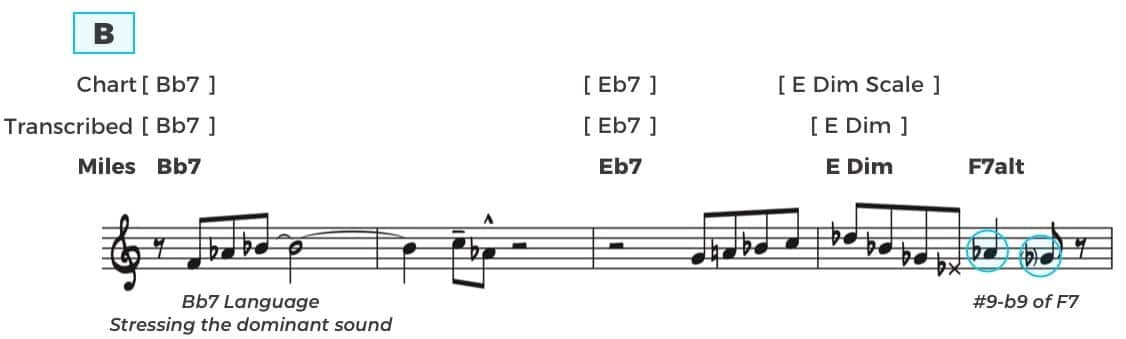

The Bridge

When Miles goes to The Bridge, you can instantly hear how he stresses the quality change…

Note here that he stresses the quality change of the Bb chord to dominant by emphasizing the Ab, the dominant 7th of Bb.

Remember how the play-along chart had Bb7 at the start of the tune and at the start of the Bridge? At this point, you should realize just how different they are.

They sound completely different, which is why it’s so easy to hear when the tune moves to The Bridge.

Here’s the start of the A Sections (NOT Dominant)…

And here’s the start of The Bridge (Is Dominant)…

The essence of The Bridge depends on this contrast by utilizing the dominant sound, which is why it’s crucial to realize that the A Sections don’t start with Bb7.

And then at the end of The Bridge, notice that he descends an Eb minor 7 arpeggio which is actually a part of the E Diminished Scale, the choice that the play-along set gives you (This arpeggio is a really nice sound/device to use over the diminished sound, especially descending because the first two notes are part of the core E diminished structure)…

But then he lands on the note Ab, which is not part of this Diminished Scale…

So what is Miles doing here?

For those last two beats, Miles uses the #9 and b9 of F7 implying an F7alt chord, the V7 of Bb, to push his line back to Bb.

If he were limiting his line to the E Diminished Scale, he’d never think of doing this.

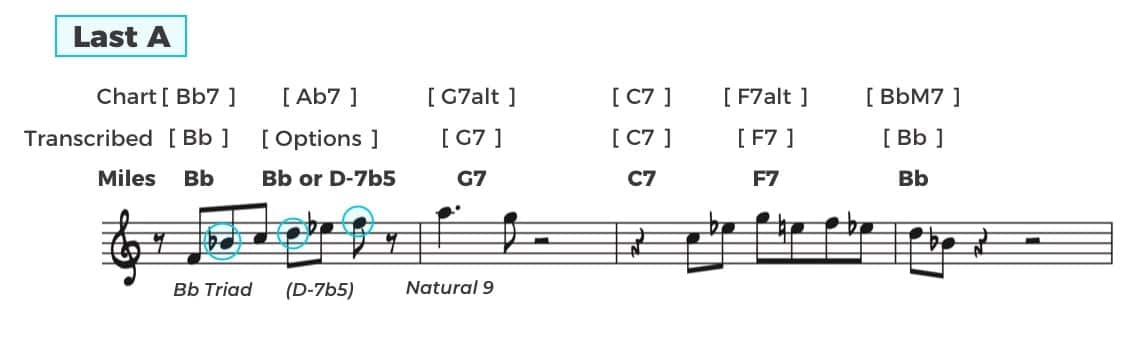

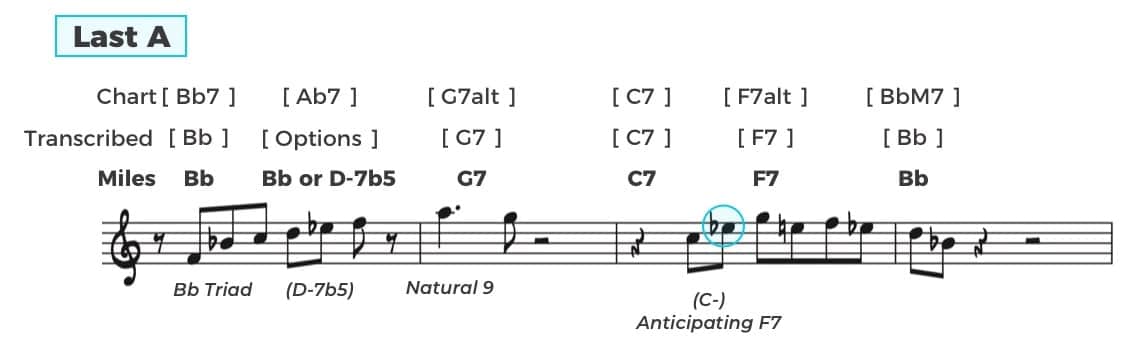

The Last A

Finally, in the Last A, Miles uses almost the same approach as before…

He again emphasizes the Bb triad in the first bar and may be using a D half diminished right before the G7, where he again highlights the natural 9th.

Then, he anticipates F7 with C minor rather than C7 to finish off his chorus.

Notice how simple Miles thinks during this entire chorus?

Not once does he think of the Ab7 chord on beat 3, in fact he basically approaches the first bar as a Bb triad, while perhaps using a little bit of D half diminished to lead into G7.

Other choruses may be different, and other soloists will certainly have a different approach. But this chorus goes you great insight into a perspective that a chart would not give you.

And notice that Miles never limits his lines to a single scale. Instead, he emphasizes chord-tones that he wishes to highlight within his lines, like the natural 9, or the b9.

Let’s put it all together now and take a listen to the full chorus…

Coming from the chart, your concept of Doxy would be very different from his, and while many of the differences seem small, they matter a whole lot.

Using a Recording to learn Doxy

After today’s lesson, it should finally dawn on you why starting with a chart of a tune will send you off quickly in the wrong direction.

As you saw from Miles, the greats are often thinking in a more simplified way than you think. And they have this option because they started their understanding of the tune from the ground up – they didn’t start with the roof.

Remember some of the key things we went over today…

- Why transcribing the melody is crucial to your understanding of the form and the changes

- How transcribing bass lines gives you insight into the changes that you would have never realized

- How to listen to the piano for chord qualities and key notes that describe a particular chord

- What transcribing just a single chorus from one of the solos can do for your understanding of the tune

- How you’d severely limit your understanding of a tune by starting with a chart

Now it goes without saying…

I did a lot of the hard work for you today. I transcribed the melody, the bass lines, the chord qualities…and I get asked all the time how I can do this so easily…

And it’s not magic. It’s a simple recipe that we’ve laid out in our Courses:

- The Ear Training Method – This is the exact material I used to train my ear. It’s simple. It’s effective and it works. Once you train your ear for a while, you will be able to hear bass lines, chord qualities, chord-tones, and everything else we needed to hear today.

- Jazz Theory Unlocked – When you know how chords are supposed to move, and you have a deep understanding behind the why, you can practically predict where everything is going. Combine this with a great ear and transcribing becomes very easy.

If you want to be able to do what I did today and study a tune from the recording with ease, picking apart all the little details that will help you play over it, you owe it to yourself to get these courses.

Keep working on these skills and enjoy applying them to other tunes in the practice room. In time, you’ll be able to use this process with any tune you desire.