When it comes to improving as an improviser, there are only so many tunes you can memorize. Only so many chord symbols and progressions you can force into your brain… After a certain point you actually need to learn how to play over these sounds.

…and truth be told, this is something that took me a long time to understand.

For years I thought that memorizing more chords, more progressions, and more tunes would change the way I improvised. I actually believed that something magical was going to happen to my playing when I memorized 100 tunes!

Unfortunately all of this time and effort didn’t transform me into the next John Coltrane.

You see, improvement isn’t about piling on more information – it’s about mastering the information that you already have. And if your goal is to play better solos, you need to start focusing on specific chord progressions and mastering them one by one.

Lucky for us, the jazz repertoire isn’t comprised of random sequences of chords that change with every tune. If you look at the big picture, there are a handful of important chord progressions that pop up over and over again…

And today we’re going to focus on one of them: the movement from I to IV.

We’ll dig into the theory behind this relationship, show you some important tunes that use it, check out some lines from great improvisers, and give you a blueprint for developing your own techniques to master this progression.

Let’s get started…

The I to IV relationship

Harmonic movement by a perfect fourth – moving from I to IV or modulating to the key of the IV chord – is a fundamental part of music.

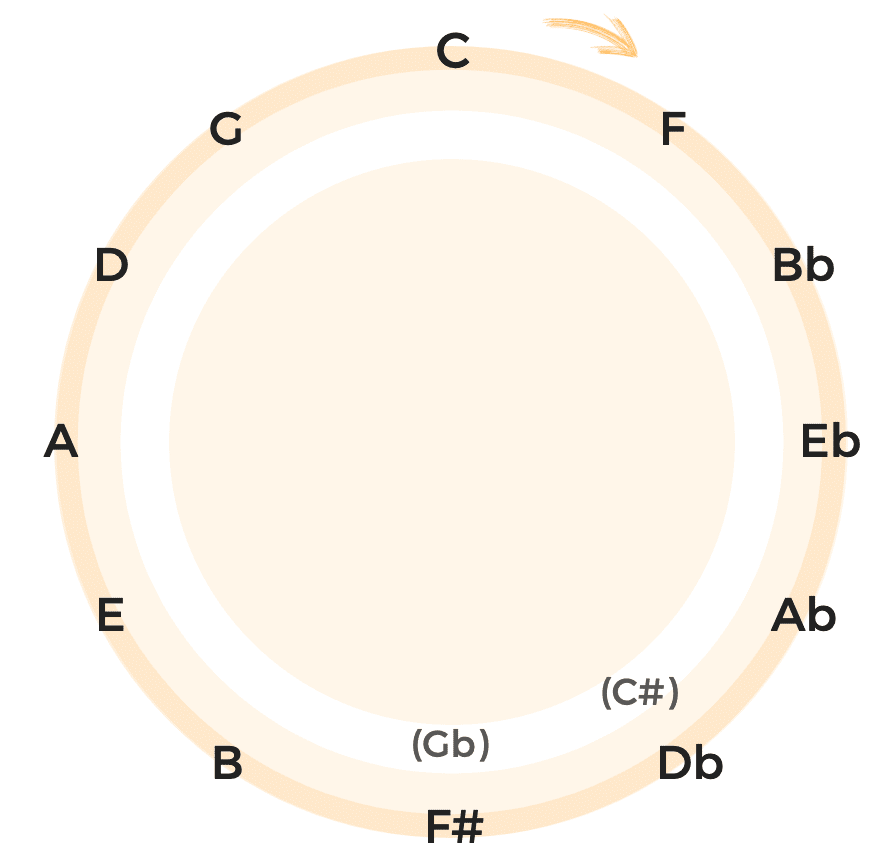

You’ll find this relationship in pop tunes, nursery rhymes, Broadway musicals, symphonic works, and countless jazz standards. And it goes back to the symmetrical relationships found in the circle of 4ths:

This root movement by perfect fourth has an inherent sense of forward motion and a feeling of arrival or resolution. This is because it’s the same as V7 to I movement (but more on this later).

Your first step in mastering this relationship should be to aurally and mentally ingrain this intervalic relationship around the circle.

A useful exercise is to visualize the root movement around the cycle in every key. Once you can do that, visualize a chord or arpeggio above this bass note.

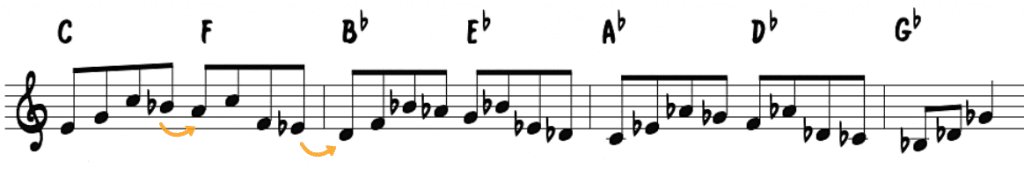

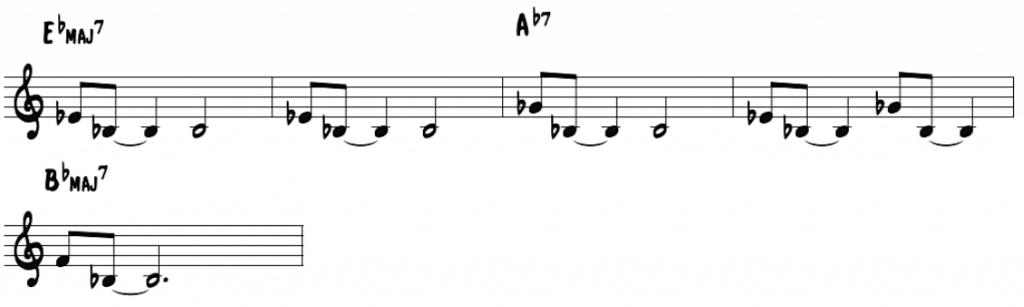

Finally, practice linear exercises that outline this movement like the example below, resolving to the 3rd of each new key:

The end goal is to ingrain this movement in a harmonic as well as a linear fashion.

Direct movement vs. Temporary modulation

When we talk about the relationship between the I and IV chord, we don’t just mean moving diatonically from the I chord to the IV chord in a single key.

As an improviser, you’ll also encounter this relationship in tunes that begin in the tonic and over the course of the progression, modulate to the tonality of the IV chord.

Think of it this way…

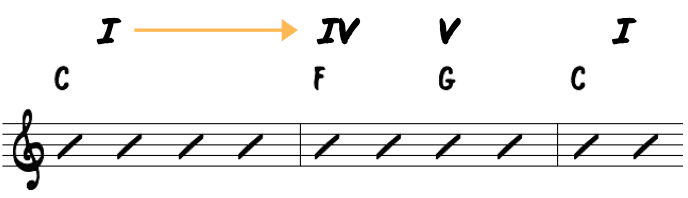

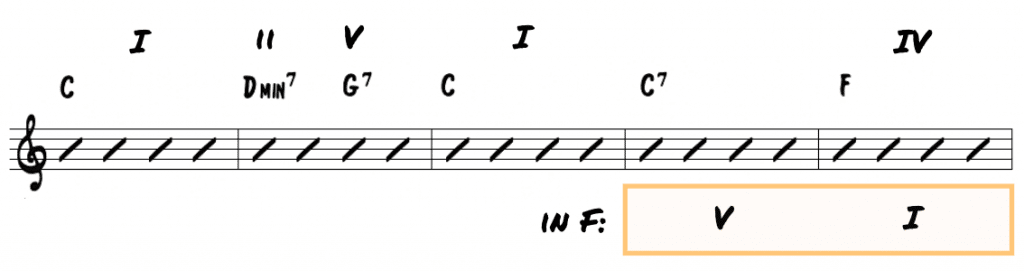

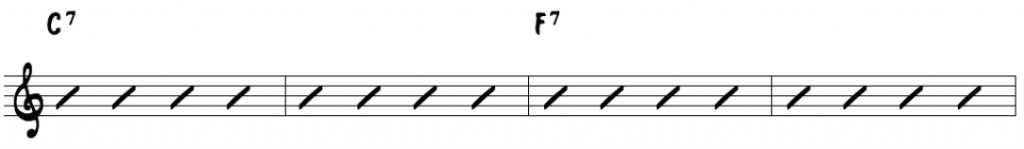

The first example is what we’ll call Direct movement – moving directly from the I chord to the IV chord. Essentially a diatonic progression in one key, like the one below:

Or in the Blues where the I chord moves directly to the IV chord:

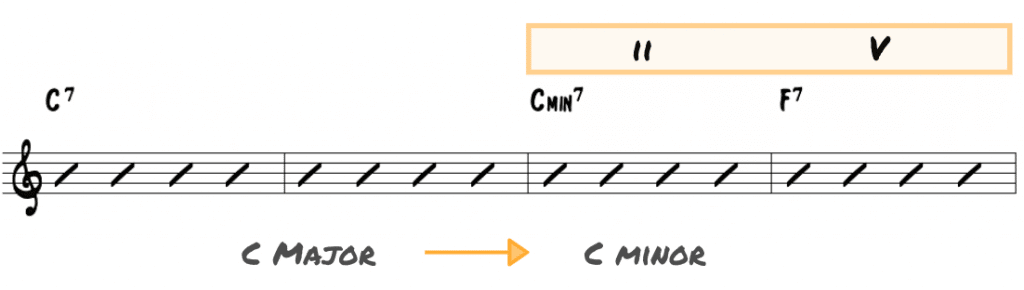

The second way you’ll encounter this movement is through what you might call a Temporary modulation – momentarily arriving at a new harmonic center.

The progression below begins in C (I chord) and quickly modulates to or arrives at the F (IV) chord:

This progression or “tune” is in the key of C, but temporarily modulates to F (the IV chord) by way of a V7 chord or ii-V-I. You’ll find this type of progression in many jazz standards.

Understanding the larger picture of the theory behind this chord movement and relationship, rather than just memorizing individual chords, will allow you to unlock numerous harmonic and melodic possibilities.

Where do you find this chord relationship?

The I / IV relationship is a vital part of the jazz standard repertoire, one of the fundamental building blocks that occur in countless tunes.

The more you study this relationship, the more you’ll hear it popping up in the standards you practice everyday. And with a little know-how and practice, you’ll be able to quickly spot this progression in any tune that you play.

Below we’ll look at four tunes in the jazz repertoire that feature this movement from I to IV…

The Blues

The most common example of I to IV movement is the blues. Take a listen to Red Garland play this progression in C Jam Blues:

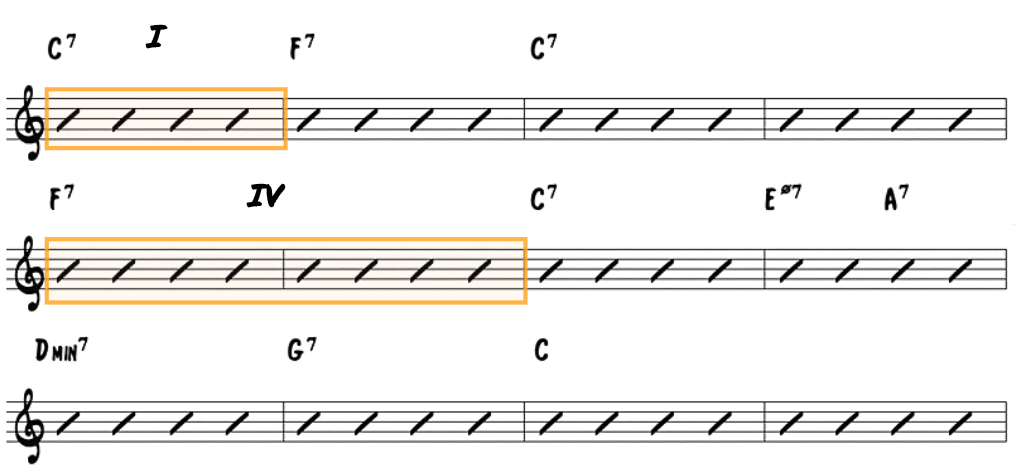

One of the defining features here is the movement from a dominant I chord to a dominant IV.

As you study these harmonic relationships, step one is knowing where the I and IV chords happen and step two is knowing how to connect them.

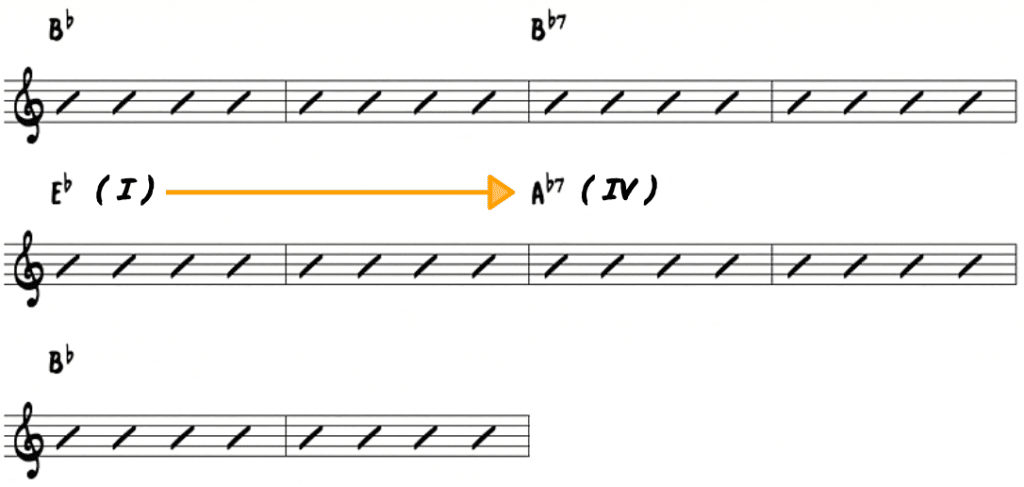

This direct movement from I to IV happens twice in the progression – between the first and second measures and again in the fifth and sixth measures:

Cherokee

The next important jazz standard that features the I / IV relationship is Cherokee.

Listen to Art Tatum play through the tune and see if you can hear where this harmonic movement occurs:

*For an in-depth look at Cherokee, including transcriptions and solo techniques, Premium Members can access this lesson.

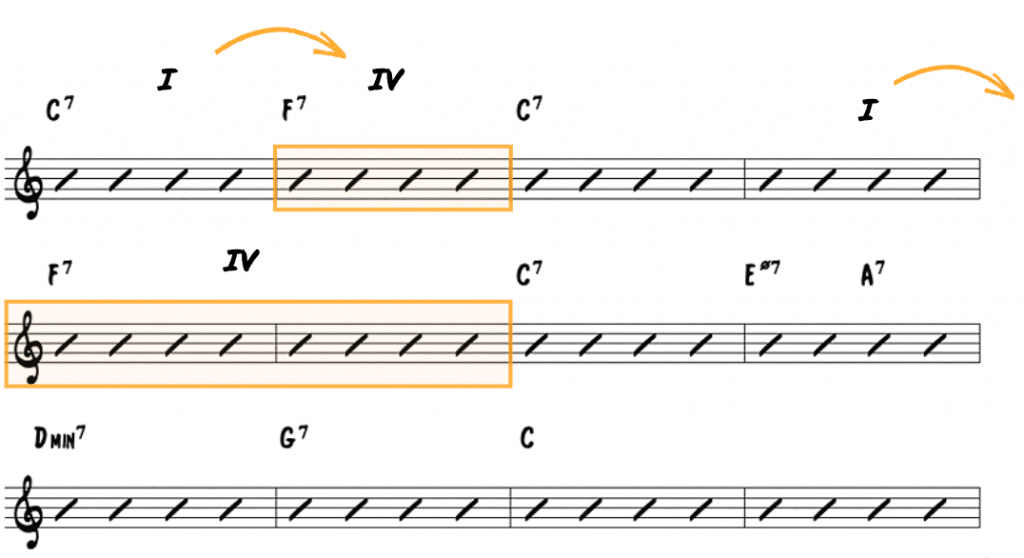

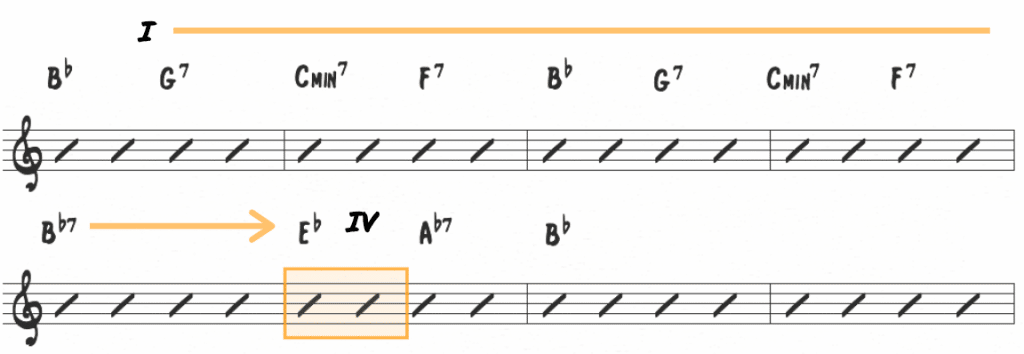

The progression begins on the I chord and resolves or arrives at the IV chord in the fifth bar:

However, this movement by fourth happens one more time in the 5th and 6th bars, moving from the IV chord to the bVII (Eb to Ab7 below):

Rhythm Changes

Another tune where you’ll find this chord relationship is in the changes to I Got Rhythm…

*For a look at 6 Essential Rhythm Changes solos, Premium Members can access this lesson.

The I-VI-ii-V progression in the first four bars can be seen as diatonic movement in the I chord and the next “arrival point” is the IV chord in the sixth bar:

This movement is subtle and goes by quickly, but is important to know if you want to master rhythm changes. Also note how the IV moves to the bVII (another I to IV relationship), the same as in Cherokee, just in a truncated form.

This I to IV relationship can also be found on the bridge of Rhythm Changes:

The bridge begins on the dominant III chord and moves around the cycle, arriving at the V7 chord. Here you find the I to IV movement not in diatonic function, but in the relationship between the chords.

Sweet Georgia Brown/ Dig

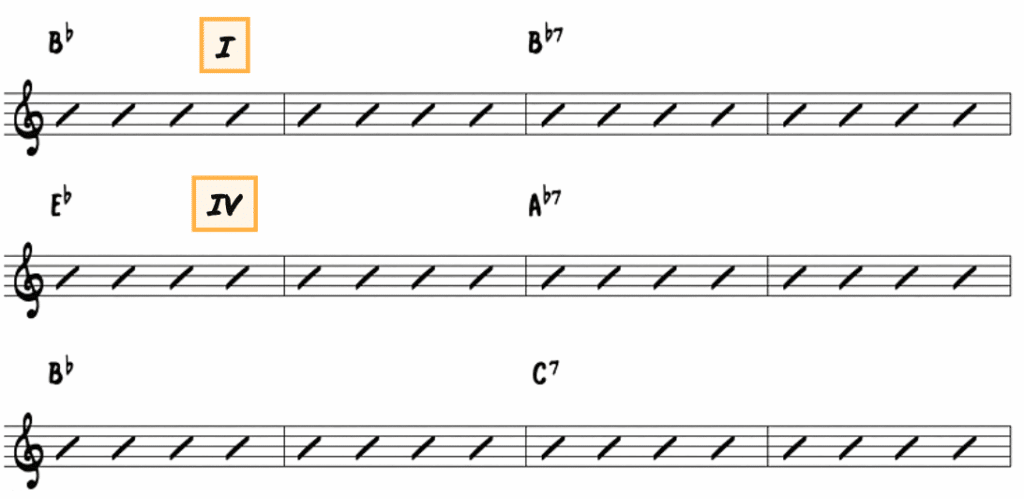

The last tune we’ll look at that utilizes this I to IV relationship or movement by fourths is Sweet Georgia Brown.

Check out Miles’ tune Dig, a contrafact or melody written over the progression of Sweet Georgia Brown:

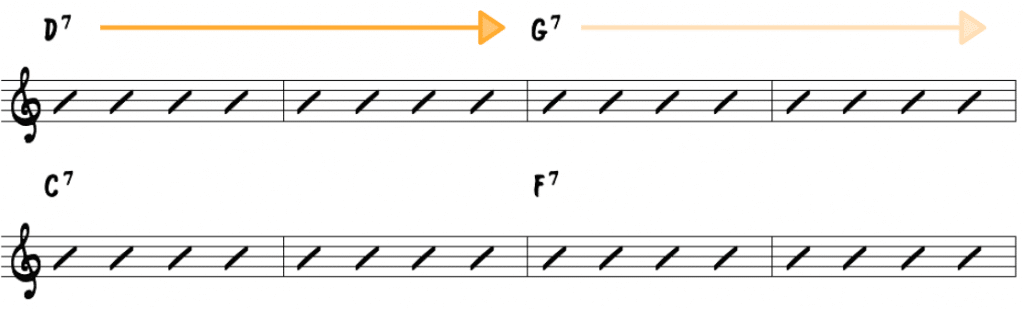

Like the bridge of Rhythm Changes, the progression here utilizes the systematic movement around the circle of fourths with dominant chords, starting on the VI chord and eventually resolving to the I:

These four standards are just a few examples of the importance of the I to IV movement. Take a peek at the tunes you already know or want to learn and I’m sure you’ll find more.

Learning to Navigate this Chord Relationship

Here’s the thing to remember…simply knowing that certain tunes have a I chord or a IV chord in certain spots or memorizing dozens of chord progressions is not enough.

It’s one thing to be able to list off the chords to Rhythm Changes or Cherokee in all keys, but it’s another skill entirely to create a solo over these sounds.

To be able to improvise musical phrases you need to develop techniques for navigating these specific chord progressions. The goal is to be able to make melodic statements, moving seamlessly from one sound to the next.

And as you can see from the number of places where you’ll encounter this progression, developing some devices to play over these spots will prove to be especially useful.

Below we’ll show you some specific techniques that you can use over the I to IV movement that you find in the Blues, Cherokee, Rhythm Changes and many other places.

It’s important to remember that the way you approach this progression and the techniques you use depends on context – the tune, the larger progression, and the quality of the I and IV chords.

Here are four techniques for navigating the I to IV progression…

Technique #1: Major to minor

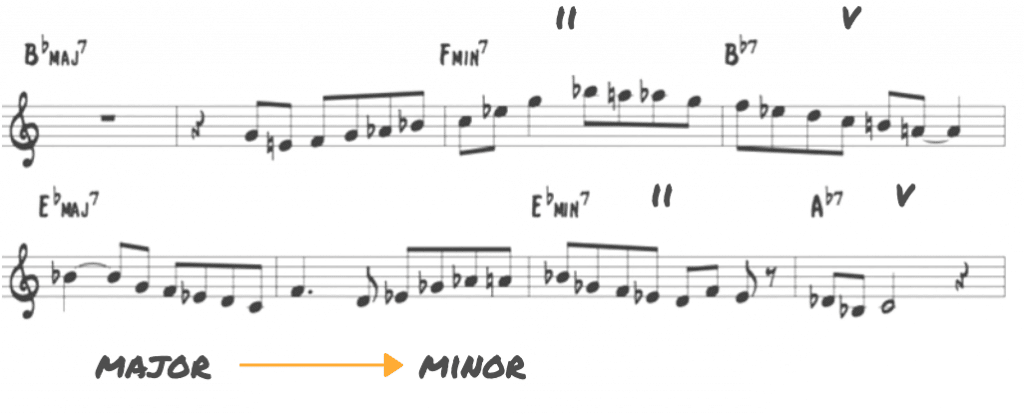

The first technique we’ll look at for approaching this I to IV relationship is moving between Major and minor.

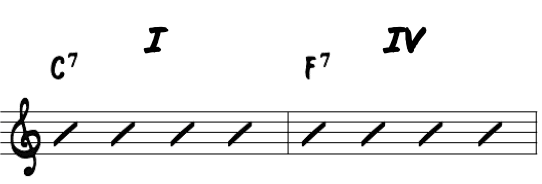

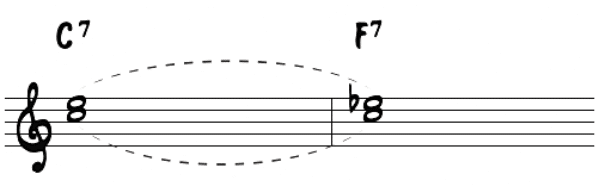

To see what I mean, take the first two bars of a C blues. When you have a I chord (C7) moving to a dominant IV chord (F7) you encounter a natural guide tone line of a major 3rd moving to a minor 3rd:

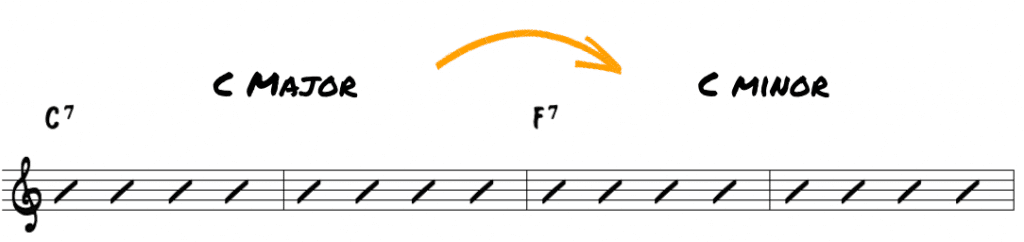

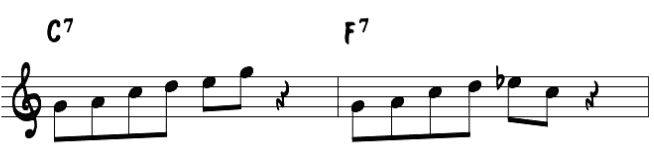

Using this resolution and common chord tones, a simple way to start approaching this progression harmonically and melodically is to think of going from Major to minor:

You can do this by utilizing triads, simple scale fragments, or melodic motifs that move from Major to minor. For instance, you might use C Major pentatonic material over the I chord and change the E to an Eb over the IV chord:

You could also switch between C Major pentatonic on the I and C minor pentatonic on the IV. And in the same vein you could use C major melodic statements on the I chord and C blues language (blues scale, etc.) on IV chord.

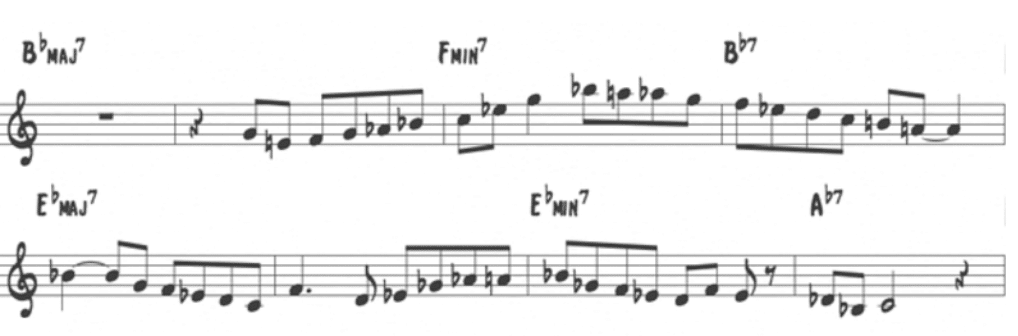

Let’s take a look at a few examples of how great players utilize this technique in their solos. Here’s an example of Clifford Brown over the 5th-8th bars of Cherokee:

In this phrase he creates a simple melodic motif in Eb Major and over the Ab7 he plays Eb minor.

Another great example is the opening to Clifford’s solo on Sandu:

On the I chord (Eb) he uses Eb Major material and on the IV chord (Ab) he uses Eb minor material, shifting back and forth between major and minor.

Where to use this technique: You can use this technique anywhere the I chord moves directly to a IV chord that is dominant:

- Blues

- 5th-8th bar of Cherokee

- Bridge of Rhythm Changes,

- Sweet Georgia Brown/ Dig

- 6th bar of A section on Rhythm Changes

Technique #2: V7 to I

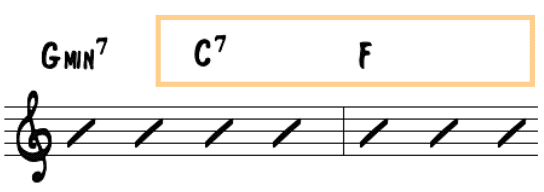

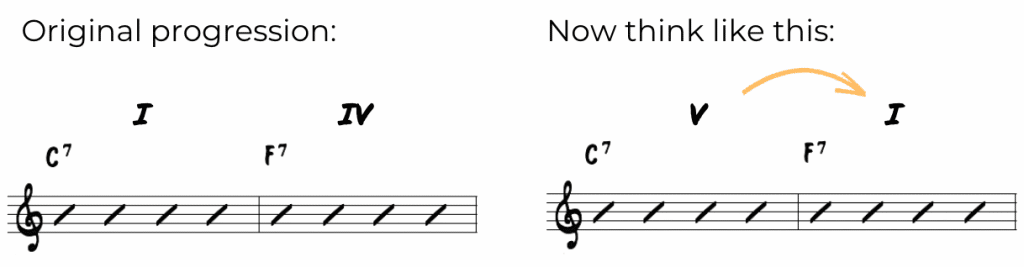

At it’s heart, I moving to IV is essentially the same relationship as V7 moving to I:

And I’m guessing this is a harmonic progression that you’ve already spent some time studying.

Another technique that you can use in your solos over the I to IV progression is to think this movement as a resolution from V7 to I:

Utilizing the natural tension and resolution of V7 to I to create forward motion and direction in your musical phrases. In other words, view the IV chord as an arrival point instead of just another chord in the progression.

By making a simple shift in the way you mentally approach this progression, you’ll unlock a number of new musical possibilities.

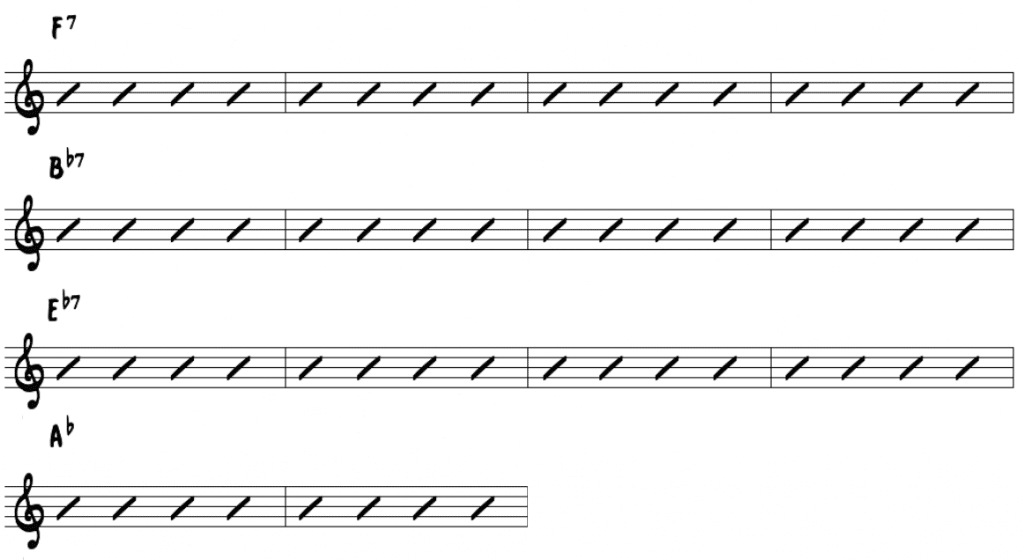

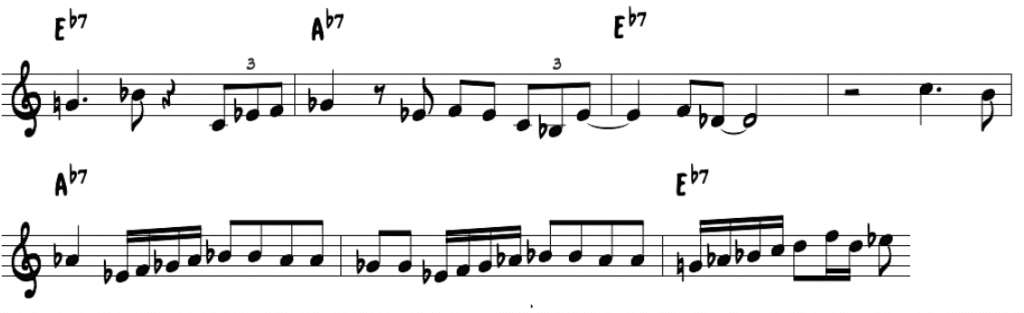

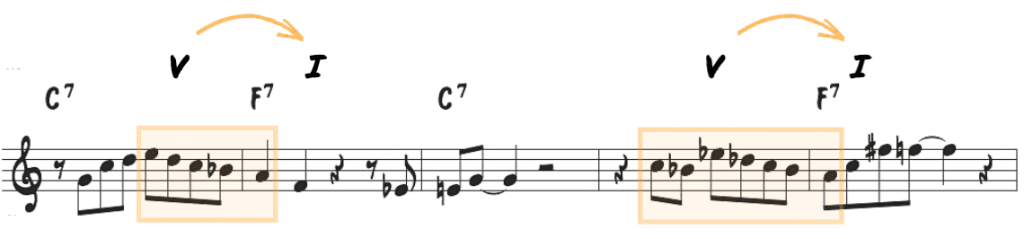

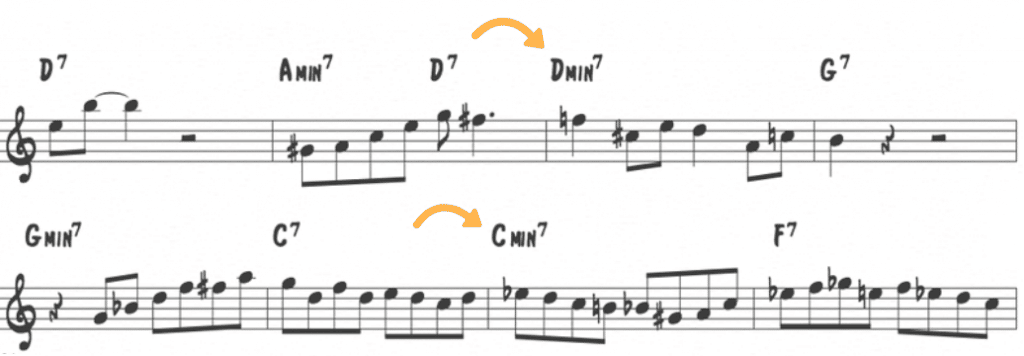

To see what I mean, let’s apply this technique to the first few measures of a 12 bar Blues. Here’s an example of a line that utilizes this V7 to I motion:

In this example, the C7 is treated like a V7 resolving to F7 as the I. The first line uses scalar motion to resolve to the 3rd of F and in the next spot, the #9 and b9 are used over C7 to add harmonic tension which resolves to the 3rd of F7:

The goal of each phrase is to resolve to the upcoming IV chord.

You can use the same technique on the bridge to Rhythm Changes. Instead of looking at this progression as four separate chords, look at this progression as resolving from V7 to I:

This will help you create longer musical phrases with forward motion through the progression. Here’s an example of a line that uses this V7 to I relationship on the bridge:

The cool thing about this is that you can use any techniques you have for V7 to I over these spots to “arrive” at the IV chord. You might apply:

- Bebop scales

- Altered dominant techniques

- Tritone substitutions

- Or any language that you’ve learned or transcribed over dominant sounds

Where to use the V7 to I technique: you can use this technique over any I to IV relationship.

Technique #3: ii-V’s

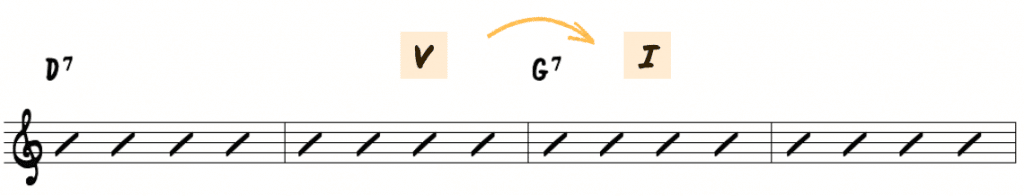

In technique #3, we’ll build on the previous technique of V7 to I.

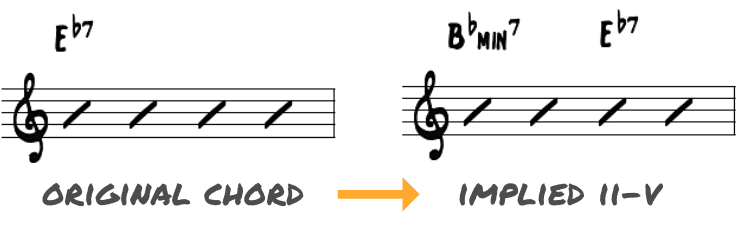

Whenever you have a static V7 chord or a dominant chord moving to I, you can imply the related ii chord or ii-V7 progression over this chord:

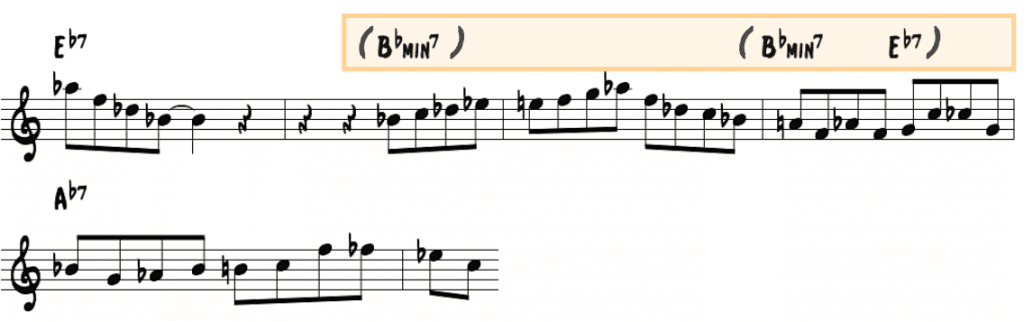

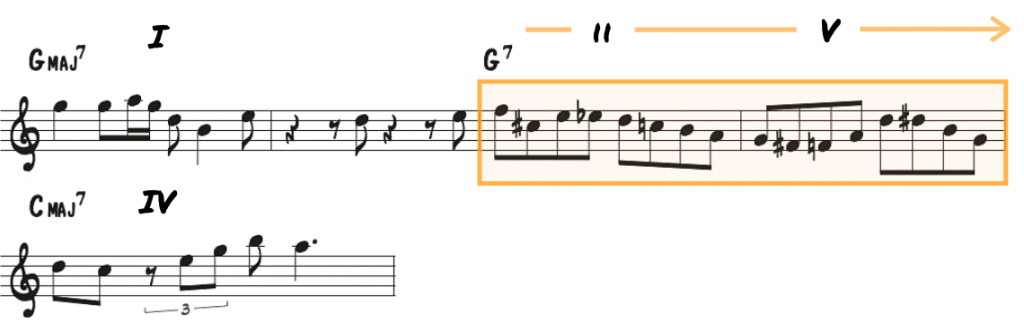

Check out how Sonny Rollins uses this ii-V technique in his solo on Dig, implying Bb- and Bb- Eb7 over an extended Eb7:

So how do you apply this concept to tunes where the I chord moves to the tonality of the IV?

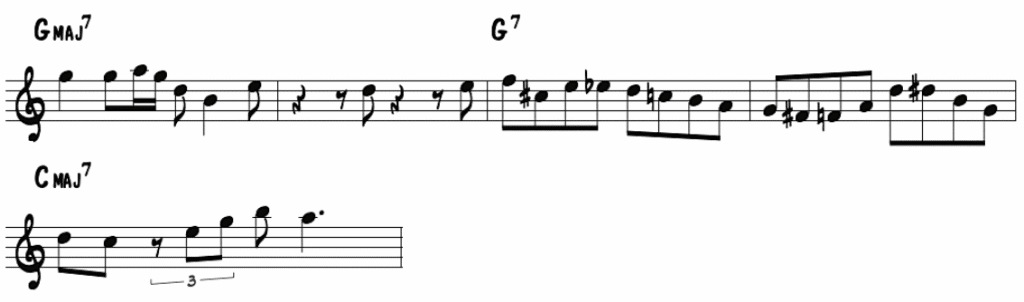

Let’s look at a few examples of using this ii-V technique to get from the I to IV chord. Check out this Charlie Parker line over the first five bars of Cherokee:

Over the G7 chord he utilizes a ii-V progression to move from the I chord in the first bar to the IV chord in the fifth bar:

This same technique can also be used in the 5th bar of the blues, moving from a dominant I chord to a dominant IV chord:

Check out how Red Garland utilizes this technique is his solo over C Jam Blues:

Where to use the ii-V technique: Anywhere you have an extended V7 chord, a dominant I chord moving to the IV (or any V7 moving to I)

- Blues

- 3rd and 4th bar of Cherokee

- Rhythm Changes Bridge

- Sweet Georgia Brown

*For more on finding and developing ii-V language, Premium Members can check out this lesson.

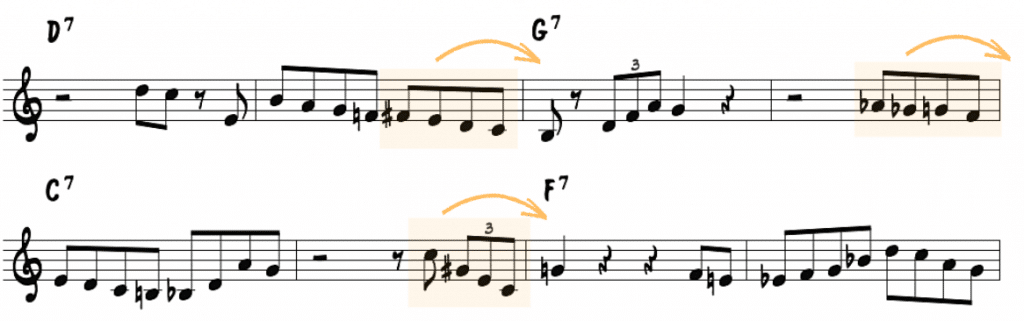

Technique #4: ii-V’s using major/minor technique

The final technique we’ll look at is a combination of technique (#1) and technique (#3) – Implying ii-V over V7 chords and using this concept to move from Major to minor.

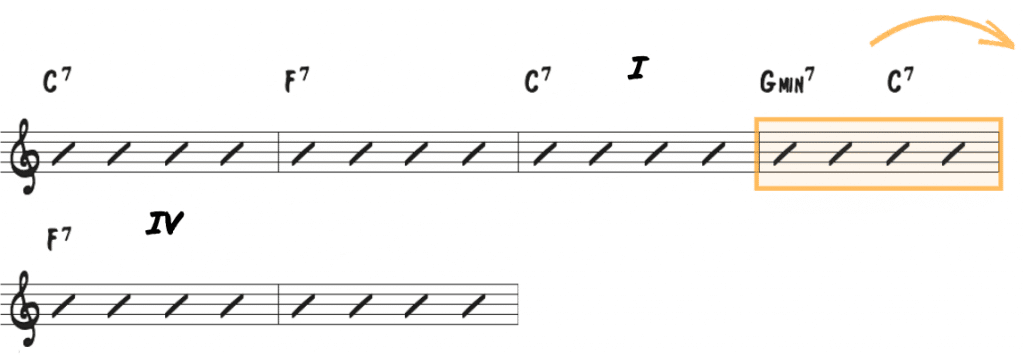

To see what I mean, take a sequence of two measure V7 chords like you’d find on the bridge to Rhythm Changes:

Over the F7 chord you can imply a related ii-V (C-7 to F7). With this substitution, you can create a smooth transition in your line by using C major over the C7 chord and moving to C minor material over the C-7 chord:

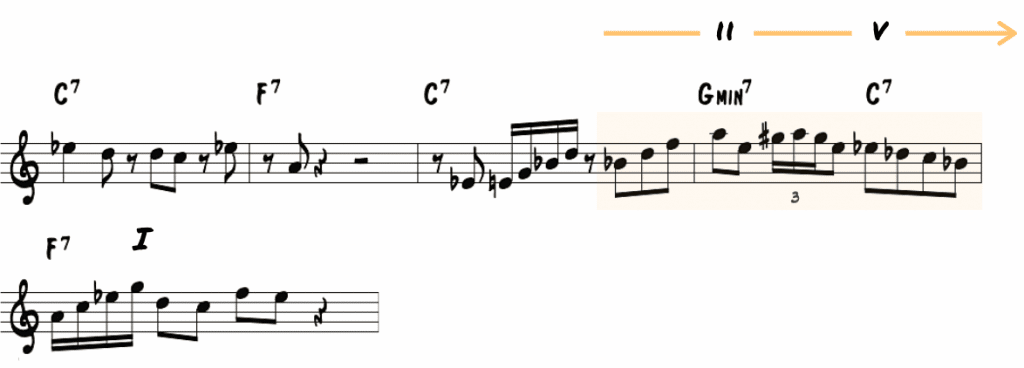

A great example of this technique in action is in Sonny Rollins’ solo on Oleo. On the bridge he plays this line:

Notice how he implies the related ii-V’s over the two bar V7 chords and connects his lines by moving from Major to minor.

Another example of this technique can be found in Tom Harrell’s solo on Ko Ko (Cherokee), over the first 8 bars of the tune:

Over the two bar V7 chords in bar 3 and 7 he implies ii-V’s, and this allows him to utilize the major minor technique between Eb and Eb- in bars 5 and 6:

Where to use this technique: you can apply this technique to a I chord moving to a dominant IV chord:

- Blues

- Bridge of Rhythm Changes

- Sweet Georgia Brown/Dig

- 5th-8th bar of Cherokee

Where to get started in the practice room

There’s a lot of information to absorb here over a seemingly simple I to IV chord relationship…

But like everything else in music, mastery comes from taking one concept at a time and practicing it slowly.

Here are a few points to remember as you head into the practice room:

- Spend time visualizing root movement around the circle of fourths in every key

- Review the two ways you’ll encounter the I/IV relationship – Direct movement from the I to IV chord in one key and Temporary modulation, moving from the key of the tonic to the key of the IV chord

- Listen for this harmonic relationship and study the progression to the major tunes that feature it – Blues, Cherokee, Rhythm Changes, Sweet Georgia Brown/Dig

- A good place to start working on and applying the techniques outlined above are on the Blues, go through every key

The four techniques in this lesson take time to master and build progressively from one technique to the next – master one and then move on.

And if you’re looking for more techniques??

Listen to your favorite players over the tunes we highlighted above. Simply find a recording you like, isolate the spots in the progression where the I moves to the IV chord and transcribe what these players are doing.

The answers are closer than you think! It’s only when you dig in and study this chord relationship, when you understand how it’s used in tunes, and when you develop techniques for soloing over it that you’ll truly change your playing.