Great solos don’t come from nowhere. The ability to apply innovative harmonic concepts, flawless instrumental technique, and appropriate musical language doesn’t just materialize out of thin air. These prized aspects of excellent musicianship have to start somewhere. However when it comes to pondering our musical idols, for some reason we can’t help thinking in this illogical and romanticized way.

From Charlie Parker to Miles to Michael Brecker we see the staggering end result of their work and can’t imagine it being any other way. They never had to work hard, those amazing solos just came out naturally, right?? The reality though, is that each great player and more specifically, each great solo has an exact origin and a traceable path from idea to implementation.

Now this idea is nothing new to musicians, but an area of contention among many is what exactly it is that goes into creating a great solo. There are many theories out there as to what it takes to become a great improviser. Just take a look at all the different concepts and methods you can study in books and the DVD’s put out by dozens of big names.

Even between great players, there are discrepancies as to what works and what doesn’t work.

Despite all of these personal methods, there is one consistent truth that can’t be ignored. When you improvise a solo, you can only draw upon what you’ve practiced and ingrained in the practice room. It’s as simple as that – if you haven’t practiced it, it’s not going to come out of your horn.

Stopping the cycle of stagnation

We all have days that are difficult and frustrating in the practice room. You’ve run out of ideas to play over the changes, you can’t seem to get your technique working, and every chorus you keep playing the same line in the same spot. The natural tendency when you run into a little bit of difficulty in your soloing is to look anywhere but yourself.

“These changes are really difficult, this tune is boring to play over, this chord progression keeps going back to the same chords…”

The fact is that the tune is not at fault here. More specifically, it is your approach that is stale, you are out of ideas to play, you are playing the same boring licks…

You can play a tune hundreds of times, even thousands, but unless you practice and ingrain some new lines or ideas, unless you spend some time learning some new language and repeatedly practicing it, you’re going to have the same old material to work with every time. This state of stagnant playing could go on for years and does just that for many frustrated players.

Let’s say for instance that you’re working on rhythm changes in the practice room right now. You’ve got a couple of lines to work with and you have some harmonic concepts you’re using in your solos. There are a couple of rough spots, but for the most part you are satisfied with the way you sound.

Now fast forward 10 years from now. Rhythm changes is still going to be the same tune, with the same changes, and the same form. Unless you’ve evolved and planted some new ideas, language, or concepts, you are going to be playing over the tune in exactly the same way.

If you can’t play it in a different key right now, it’s going to be the exact same story in the future. If you’re having trouble with technique or range, same story a decade from now. You don’t just magically get new technique, new harmonic ideas, or new language that you can put into your solos because time has passed. If you don’t practice these ideas and plant them into your mind, they will never come out in your playing.

It’s inevitable that the tune will be the same in the future, but your playing and language should definitely not be.

This is something that many musicians don’t realize, or choose not to confront. They think that if they simply keep playing a tune for years that they will automatically get better and have new, fresh ideas to play over those changes. Well, I’ve got news for you…

You harvest what you plant

Imagine that your ability to improvise is like a farmer’s planting field. A big open field of freshly plowed dirt waiting to grow the crops of your picking. The seeds that you plant and the time you spend cultivating these new crops in the practice room will determine what you will be able to do in performance.

It’s important to remember that everything that you do in the practice room will take root and shape the improviser you are going to become weeks, months, and even years from now. You have a choice here, so be careful as to what you plant and cultivate on a daily basis. You can cultivate a variety of ideas and and tend to them everyday, or you can carelessly throw a few licks into that dirt every now and then and how for the best.

There is a consequence, however for the work that you do or don’t put in during your practice.

This moment of truth for the farmer is harvest time, the time when he can reap the fruits of his hard labor. For the improviser this moment comes in an improvised solo in performance. On stage, some players have a bountiful harvest to pick from, many different kinds of ideas and techniques that they’ve developed for months. These players can play with freedom and ease, sustained by the confidence and knowledge gleamed from hours of practice.

For others less prepared, they are left with a barren field; a few crops that were carelessly planted and tended to very rarely. Come harvest time they have a few withered plants to choose from: a couple of scales scales barely practiced, a melody and chord progression quickly learned from the real book, and one line memorized in one key. It’s safe to say that this player is going to have a tough time surviving the winter months.

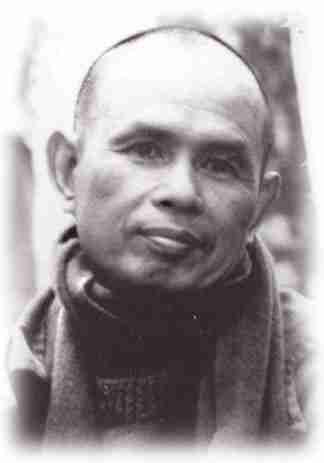

When you plant lettuce, if it does not grow well, you don’t blame the lettuce. You look for reasons it is not doing well. It may need fertilizer, or more water, or less sun. You never blame the lettuce.~Thich Nhat Hahn

Just as a farmer can only harvest what was planted and carefully tended to during the spring and summer months, an improviser is limited to the skills and language that they’ve ingrained through long hours in the practice room. You can’t blame the tune or chord progression for a bad solo, you can only blame the soloist and the preparation they’ve made in the practice room.

Careless practice and stale ideas lead to a bounty of mediocre solos every time.

Planning for the future in your practice

One of the hardest things to deal with in your development as an improviser is the time it takes to see improvement, actual results in your day to day improvising. With most things we deal with on a daily basis, you get what you ask for right away. Pay for X at the store, you get X. Put the time in at the office, you get a paycheck. Plain and simple. You put in the time or effort and you see the results right away.

With learning to improvise however, this is not the case at all. It takes weeks sometimes even months for the ideas you’re practicing to show up in your unconscious, everyday playing playing. The things you are working on in your practice today somehow shape the player that you’ll become a few months from now.

This is a challenging concept to grasp and one that is difficult to stick with. The ideas and techniques you focus on this week will slowly make their way into your playing and be fully usable at some point in the future. Today you can transcribe a solo or learn a line in all keys, but when you go to solo tomorrow, they won’t be there and this can be frustrating.

Why does this tune still feel hard to play over? I memorized the changes and melody, I learned some lines and harmonic devices to use over the progression, I transcribed that solo two weeks ago…

Trust the process

Ideas need to incubate. Technique needs time to develop in your muscle memory. Harmonic concepts need to marinate in your mind and ears. You need to sleep on it.

This is what it takes to eventually see these ideas and techniques come out in your playing one day in the future. Michael Brecker mentions this in passing in this interview. Those ideas that you start today might not be a solid part of your playing until months from not, but if you want to evolve as an improviser, this is the direction you must take.

Apply this concept today

Take a tune that you’ve been working on recently. Instead of playing it over and over with a play-a-long, using your same old lines and patterns, try something new. Plant the seeds of change.

Take the blues for example. You probably have some lines you’ve worked out and some harmonic concepts that you rely on to get through the changes. And, chances are you might be getting bored using these ideas all the time. No worries. It’s time to slowly work some new ideas into your playing.

Start by picking a piece of language or a harmonic idea to apply to the predictable motion of those 12 bars. For example, try inserting a ii-V in some key places into that standard progression (see this article). Or try employing some V7 language or ideas that you’ve transcribed over the major chords in that blues progression. The possibilities are infinite.

This idea is the same with learning to play in a new key or introducing a new technique into your playing. Start slowly and be consistent. It will be difficult at first and you may not see change for some time, but keep going. You are introducing skills that you don’t have and if you stick with it, you’ll have these skills in a relatively short amount of time.

This whole process may seem like a lot of work, and honestly, it is. But, look at the alternative. You could stick with your “go to” licks and safe, familiar tunes and keys in your solos. Practicing with this mindset is not challenging and you don’t really have to practice at all. You’re playing the same lines you’ve learned years ago and five years from now, you’ll be playing the same solo. Ten years, twenty years from now – you guessed it, same solos, same lines, same licks.

If this sounds good to you, then by all means keep on truckin! However if decades of mediocrity is not your cup of tea, then start planting some new ideas and techniques into your practice today. One small idea cultivated carefully today will produce big rewards for the improviser that you will become in the future.