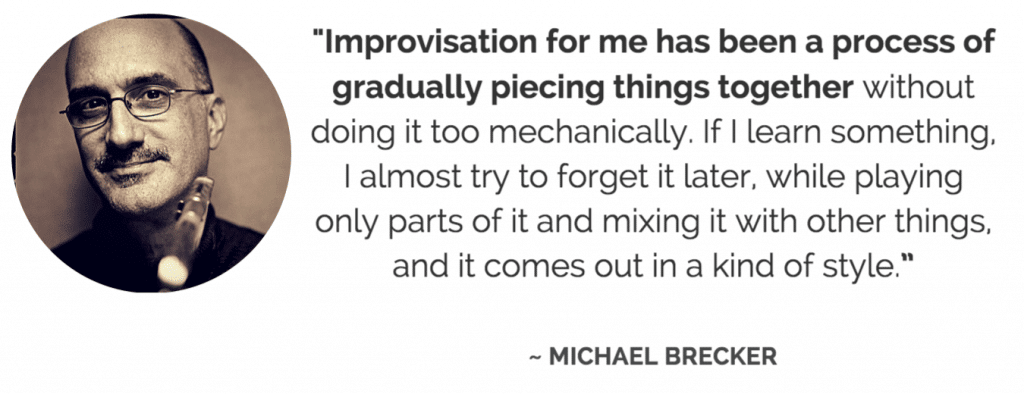

Michael Brecker talked about it. Mulgrew Miller mentioned it time and again in masterclasses. And if you’ve spent any time on Jazzadvice, you’ve seen multiple articles about the importance of learning it. But why should you start thinking about jazz language?

You’re already practicing technique, running scales, and listening to a ton of your favorite players…and you’ve even noticed some progress in your ability to create solos.

So why should you add one more item to your already packed practice list?

It’s a good question…and one that many players shrug off.

But not so fast! Language is the key that can take you from the player that’s frustrated with scales and chords to a soloist with unlimited creative ideas.

You just have to approach it the right way in the practice room.

Let me explain…

The 3 stages of learning jazz improvisation

Musicians of all levels are drawn to jazz improvisation.

Because we all want a chance to step into the spotlight to take a solo…

But no matter what your skill level is, every player encounters the same struggles when it comes to finding their voice on an instrument.

You see, we don’t get a guide book for learning how to improvise. And finding an effective practice routine can sometimes be a big mystery.

Just because you’re spending time practicing doesn’t mean that you’re automatically going to get to the next level. To improve as a soloist, you’ve got to practice the right things.

And this is where learning the jazz language can make all the difference.

But it’s not that simple – most players go through 3 stages of learning jazz improvisation…

1) The “no language” stage

This is where we all start…

Hopeful and excited about making music, but confused as to where to begin. The second you try to improvise there’s an imposing mountain of information standing in your way.

So you start with the building blocks of music theory: major scales, modes, triads and chord tones…

In lessons you learn rules for navigating chord progressions and in the practice room you try to piece everything together. Frantically looking for guide tone lines and the 7th and 3rds of chords as the changes fly by.

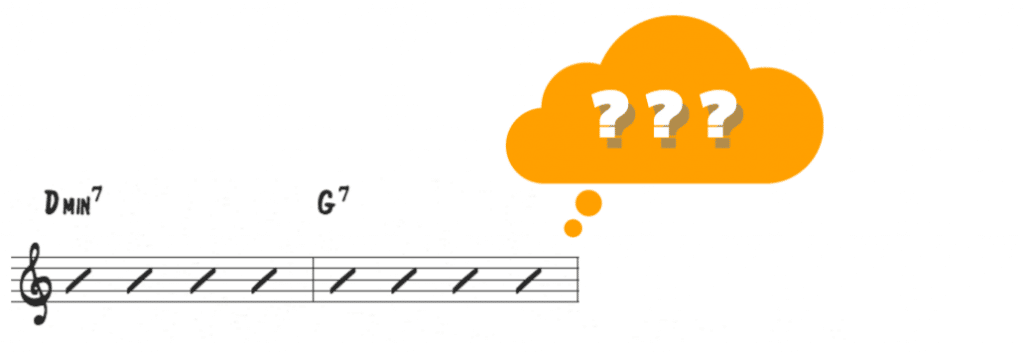

You know the rules of music theory, but when you actually try to use this information to create music you draw a blank:

No matter how many times you practice those scales and arpeggios, you’re still left wondering how you’re ever going to turn those 8 notes into a solo that sounds like John Coltrane.

Hint: it’s going to be a mystery until you start thinking about jazz language!

2) The “one lick” stage

Along the way you pick up some inside information…

A book of transcribed Charlie Parker solos. A line that you learn from a friend. A trick over a minor chord that your teacher shows you.

This is a lick. A singular line based in music theory. You start on a chord tone and follow the pattern. It sounds cool, but you have to think about it to play it…

For example, let’s say you learned this lick over a G7 chord:

Now every time you see a V7 chord you can insert your lick by starting on the root of the chord.

Sure, you’re still trying to piece together scales for the rest of your solo, but now you can use this lick as a lifeline when you get stuck.

And every new tune or solo you take is a chance to insert “your lick” into the chord progression.You can rest assured that you’ve got dominant chords covered anytime you see them.

But if you’re honest with yourself, you’re still stuck when it comes to being completely free and creative in your solos. You’re slowly noticing that there’s a difference between licks and jazz language.

3) The jazz language stage

At some point enough is enough! You’ve got to go out there and get this information for yourself.

This means transcribing solos.

Spending hours listening to your favorite players, singing along with their solos, and learning them on your instrument phrase by phrase.

The information isn’t written on a page anymore, the notes aren’t spelled out, it’s all in your ear…

Your practice includes time dedicated to transcribing language, learning lines in all 12 keys, and working on ways to add your own spin on things.

Like every player, most of my harmonic and rhythmic language comes from the tradition of jazz. Jazz is a language that we all learn to speak, and my playing techniques are built from studying the styles of my favorite musicians. I also incorporate classical harmonic and rhythmic concepts into my improvisation. ~ Seamus Blake

Let’s say in your listening you hear a solo that grabs your ear. So you slow it down, transcribe it, and memorize it on your instrument.

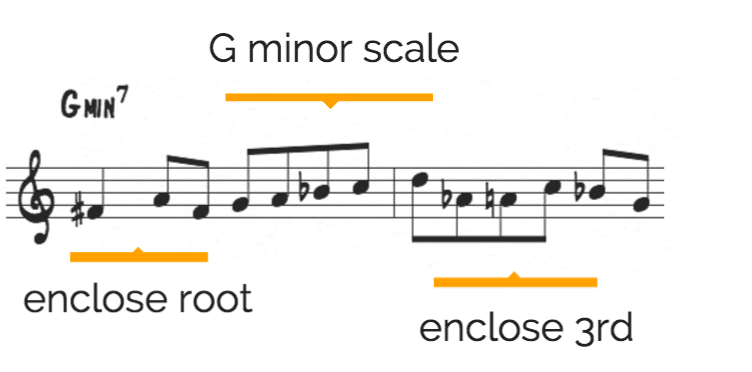

And in that solo, maybe there’s a particular line that stands out – a line that you want to steal for your own solos:

So you take that line and study it. You need to figure out why it works:

- What chord(s) is it used over?

- What chord tones does the line use?

- What are the goal notes of the line?

- What musical devices are at play?

- What makes it unique harmonically or melodically?

Then you learn it in every key. Taking it apart piece by piece, understanding the mechanics of the line. This is one piece of jazz language.

Now on a minor chord, instead of a drawing a blank or inserting a static lick, you have a piece of language that you can use as a starting point. And because you know how the line is constructed, you can recreate it in any number of situations.

This is the power of jazz language.

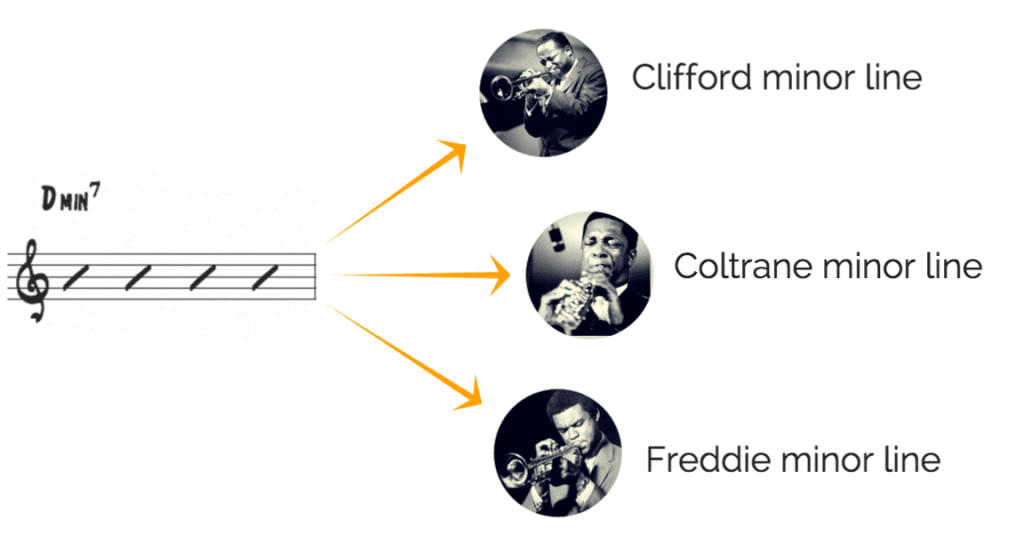

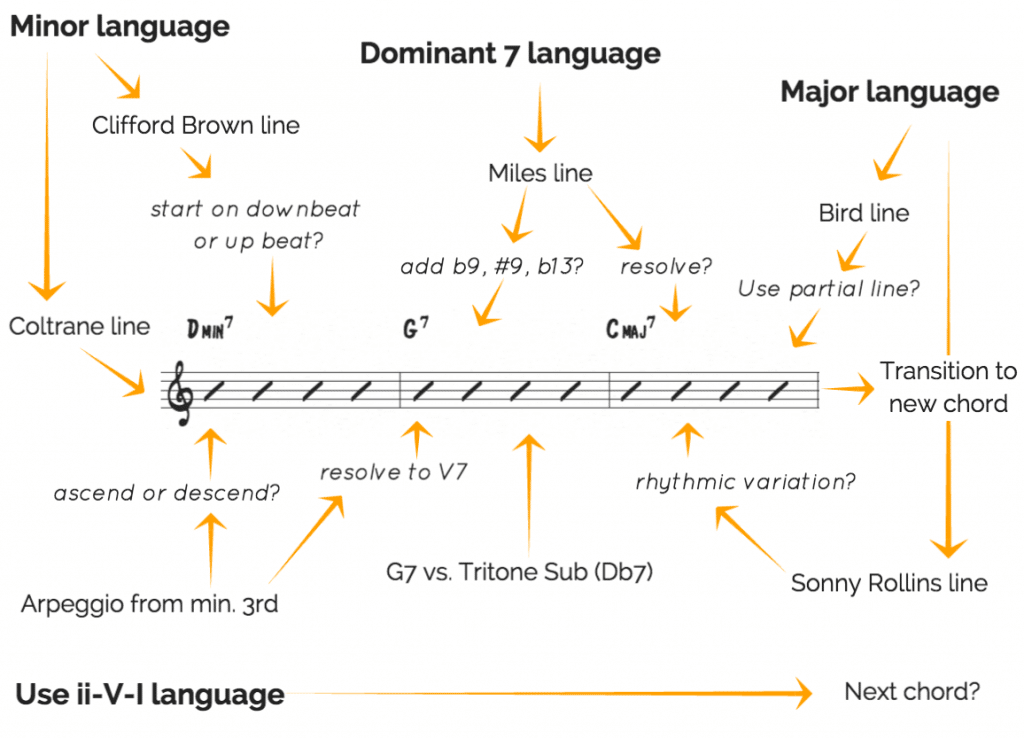

And after more listening and transcribing, you’ll end up with multiple pieces of language for every chord…

But just because you figured out and memorized the notes to a few great solos doesn’t mean that you’re automatically going to get better or have a musical epiphany. You must develop this language…

From guessing to unlimited ideas

When you add in variation and creativity to these language options, you’ll come up with infinite things to play.

And to do this you need to spend time practicing your language until you attain freedom with it in your playing.

Once you master the original line in all keys, start exploring the musical applications for it. Some options for varying or altering language could include:

- Rhythmic variation

- Harmonic alteration

- Shape and melodic direction

- Phrasing and rhythmic placement

- Using the entire piece of language or just part of it

- Motivic development and resolution

With all of these options and some good old fashioned creativity you can literally come up with hundreds of ideas to play.

Remember, the more language you have, the more options you’ll have for creating musical ideas:

Instead of a confusion when you see a chord progression or relying on one lick to force into a solo, you can approach any solo with musical freedom and possibility.

Want to get to the next level with language and unlock your inner improviser?? Be sure to check out our Jazz Language Course – Melodic Power

Now you’ve got options…

With a few pieces of language and some creativity, suddenly you are improvising.

Combining and modifying the language that you’ve transcribed from your favorite players. Mixing these lines with your very own musical ideas and creating music on the spot…

Can you make up something completely new in your solo? Sure.

Can you play a line from one of your favorite players note for note? Absolutely.

How you approach each solo is entirely up to you, but now instead of guessing at notes from scales or inserting licks, you are making musical statements.

And the more language that you learn and practice, the more you’ll find yourself creating your own ideas. Taking a piece from one player and combining it with the rhythm from another, all performed with your own sound.

This is improvising, and it all starts with language.