Recently I’ve been studying and transcribing a lot of Miles from around 1956-1957. Albums like Cookin’, Relaxin’, and Workin’. More than the notes or the harmonic devices in his solos, the one thing that sticks out about Miles is his sense of phrasing. This is what sets him apart and why so many listeners connect with his sound. Miles could play anything he wanted, but he always plays musically.

It takes an advanced and honest musician to improvise a melody that they are hearing in their heads amid the wash of constantly moving chords and time. And it takes an even more mature musician to not play all the scales, and patterns and language that they’ve practiced for hours.

Most people don’t realize how much work and focus it takes to get to the point that you can free yourself from the theory and play something that you’re hearing and feeling.

This idea of phrasing and creating meaningful musical statements is one aspect of improvising that is missing from a lot of players’ solos. Improvising is not just using scales or inserting a pattern into a chord progression, in the end it’s all about creating music and performing personal melodies.

What is a musical phrase?

When you improvise a musical phrase, you essentially become a composer, creating new melodies on the spot over an established chord progression. Therefore, studying or at the very least becoming familiar with the elements of composition is essential for creating a successful musical phrase.

Let’s consult a few passages from Arnold Schoenberg’s work The Fundamentals of Musical Composition. He opens his discussion about composition by focusing on the musical phrase, and the same applies to improvisation:

- “The smallest structural unit is the phrase, a kind of musical molecule consisting of a number of integrated musical events, possessing a certain completeness, and well adapted to combination with other similar units.”

- “The term phrase means, structurally, a unit approximating to what one could sing in a single breath. Its ending suggests a form of punctuation such as a comma.”

- “The mutual accommodation of melody and harmony is difficult at first. But the composer should never invent a melody without being conscious of its harmony.”

- “Rhythm is particularly important in moulding the phrase. It contributes to interest and variety; it establishes character; and it is often the determining factor in establishing the unity of the phrase.”

From this we can gather that the effectiveness of a phrase comes down to three main elements:

- Thinking in terms of a complete musical statement

- An awareness of the harmonic background

- Playing with rhythmic definition

The idea of phrasing is especially important in Schoenberg’s music. In abandoning conventional harmony, chordal construction, and ignoring the pull of V7 to I with his compositional system, the melody and phrasing of each piece are critical to the listener – and this was something that Schoenberg was very aware of.

Hearing a musical phrase that is stated and then developed is innate in every listener, whether it’s conscious and studied by the performing musician or unconsciously felt by the casual listener.

To the non-musician, listening to bebop may be as bewildering as a music student’s first encounter with 12 tone music, but in both cases the ear’s natural inclination toward melody and repetition is the life raft that saves us as we get swept away by unfamiliar harmony.

No phrasing, no listeners

I’ve seen hundreds of live performances, and sitting in those audiences, I’ve also observed thousands of listeners. Seeing the audience reaction to a performer can reveal some interesting clues about performing.

On some nights you can walk into a jazz club and see the audience hanging on the soloist’s every note, and on other nights, the audience is strangely uninterested, shifting in their seats and looking at their watches.

What does one player have that the other does not?

When a performer is not getting the listener’s full attention, it’s usually because one of those three elements of musical phrasing is missing:

- The soloist is not making musical statements or playing musical ideas.

- The soloist is not able to navigate the harmony, is not making the changes, or is getting lost in the form.

- The soloist is not playing with any rhythmic character, stringing together 8th notes or playing with no regard to the time or rhythmic content of the solo.

If the above three descriptions sound like your improvised solos, then it’s going to be tough finding someone to listen to you for an entire solo.

The same phenomenon happens with audiences listening to a public speaker. If the speaker is not prepared, doesn’t know the subject, and rambles on and on the audience subconsciously starts to turn off.

It makes sense: Why invest time into listening when the performer has clearly not invested time into presenting his ideas?

We’ve all seen these types of performances and most likely have been in them ourselves. All of these factors destroy the connection to the listener. We easily get lost in the tangled web of notes and chords, when we should be communicating with the audience.

Scales are important, but they are meant for the practice room, not the stage. If you want to get to the next level playing and if you want to communicate your musical message effectively with the listener, you need to get beyond the notes.

You need to speak in musical phrases…

Phrasing prerequisites

Understanding what a phrase sounds like is important, but there are a few things you have to develop musically before you can start improvising your own phrases.

Phrasing can’t happen if you’re still thinking about scales and chord tones. It won’t happen if you have to stop and remember the next chord in the progression or the key that the bridge goes to. If you’re thinking about every single note that you play, it’s really hard to think in phrases that connect over the larger form of the entire progression and tune.

If you want to craft musical phrases in your solos you need to begin by being able to hear the difference of chord qualities (Major, minor, V7, etc.), you need to know your chord tones, you need to internalize the time and feel of a tune and you have to know a tune to the point where you can sing the melody and chord progression.

Musical phrases don’t come from an intellectual point of origin, they come from your ear and your inner musicality.

Start by thinking in bigger chunks of time and aim understand the chord progression aurally. Looking beyond those individual chords. Visualize, mentally and aurally, what the whole chorus looks like and envision what your first statement might be and how you are going to develop it.

Craft your musical message for the listener, not with individual notes, but with a complete musical sentence.

Developing your phrasing

The blues is the perfect vehicle to work on phrasing, a 12 bar form with little harmonic motion, I – IV – I – V7 – I.

The movement from the I chord to the IV chord and back to the I chord is perfect for developing a simple musical phrase. Play an idea on the I chord, then develop it on the IV chord and complete it on the ii-V going back to the I chord. A statement and then an answer to that statement.

For example, listen to Miles solo on “Blues by Five”:

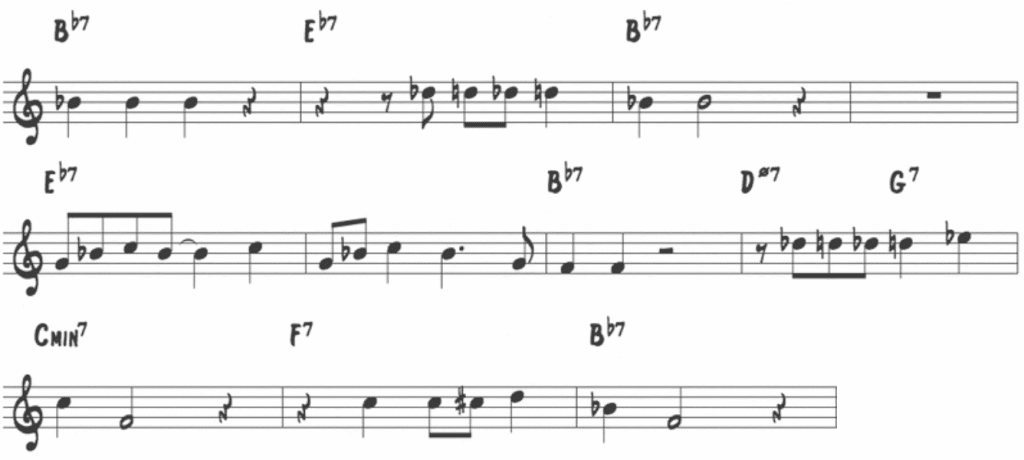

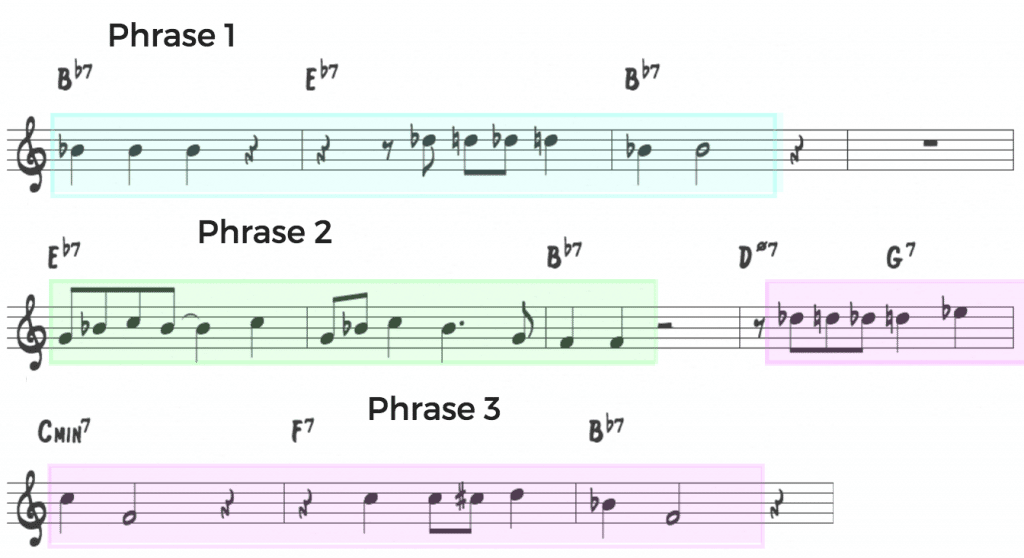

Let’s take a look at just the first chorus:

Now let’s look at those 12 bars, not from the standard chordal analysis point of view, but from the idea of phrasing. Instead of thinking about each and every chord, hear those 12 bars as one piece. Hear what that form sounds like as a whole and listen to how Miles navigates this form.

In the first chorus of his solo Miles plays three distinct phrases:

One idea seamlessly and logically leads into the next. There is room to breathe after each phrase and the listener can easily follow the development of the line.

When we analyze solos on a piece of paper we get stuck in a note to note approach, but this is not the way we hear. Turn on a record and you’ll quickly realize that you don’t hear one note at a time, you hear phrases and musical ideas. This is how you should start to think of the solos that you’re transcribing and eventually how you should envision your own improvised solos.

Play what you’d sing

Another important part of phrasing is aiming for a vocal quality in your lines, as if those note you’re playing would be something you would naturally sing.

Chet Baker is a great example of a player that always played what he was hearing or feeling. It didn’t matter if he was playing his ideas on trumpet or singing them, the same musical phrasing and feeling was there.

Check out Chet’s solo on “It Could Happen to You”:

Great musical phrasing is like a conversation. Make a statement and then follow that up with an answer. It’s logical and makes sense and you can follow the development of the story. Your statement could have a rhythmic motif, or a set of intervals, or even a small piece of language that you’ve transcribed. Whatever it is, the phrase should begin with something you’re hearing.

Musical phrasing is the natural result of listening to hundreds of records, transcribing solos and the melodies to tunes. However it is also the result of developing your ears, studying theory and ingraining chord progressions and melodies to the point that you don’t have to consciously think about them.

After some time the idea of making a musical statement that you’re hearing in your head will feel natural to you. The same way that you learned to speak sentences, you’ll start to play improvised musical phrases that make sense and develop throughout your solo.

Keep in mind that thinking in phrases is just the beginning. Once you get used playing phrases, you can use some ideas in this article or this article to develop this idea even further. You can take this idea as far as you’d like, but if you only do one thing, make sure it’s getting in the mindset of phrasing every time you take a solo.