Setting goals is an essential part of improving at anything you do…whether it’s learning a language, getting in shape, or mastering an instrument and building your skills as an improviser.

You see, your goals are those big targets that you’re aiming for out in the distance. The accomplishments you daydream about, the skills you wish to have one day, and the techniques you’d love to add to your musical toolbox.

Making goals gives your practice purpose and imbues a sense of motivation into your daily routine. A goal helps you find direction for getting to the next level!

Sounds like positive things for your development as a musician, right?

But what you might not realize is that having a goal is just the first step in a multi-layered process. And when it comes down to the nuts and bolts of getting work done in the practice room, big goals are surprisingly ineffective.

…in fact they can even slow down your progress and throw you off track!

What the best players understand is that there’s a difference between making a goal and the daily work of actually achieving it.

Today we’re going to show you exactly how to approach any goal you have in the most effective way…

Setting goals vs. Improving

If you’re like me, you have a bunch of musical goals rattling around in your mind that you’ve accumulated over the years:

“I want to play Rhythm Changes like John Coltrane…I want to solo over Cherokee at crazy fast tempos…I need to master this list of tunes for a jam session…I need a better high range on my instrument.”

These are all good aspirations to have, but the question you need to ask is: What’s the next step?

What happens after you make this goal and head into the practice room? And how exactly do translate this big idea into tangible exercises to practice? This is why big goals can be so troublesome…

A big goal is great for a long-term target, but in terms of the specific steps getting there, they aren’t much help…in fact they’re vague and overwhelming.

The key to utilizing them however, is knowing their particular purpose or role in the process:

- What goals are good for – planning, inspiration, direction, a reason to practice, thinking big, opening up new possibilities

- What goals aren’t good for – the specific details that go into a skill, small achievable tasks, defined exercises you can practice, determining what you need to work on

Most of us are good at making goals, however the problem is that we often stop there…

We get stuck in the goal setting stage and never get to the step of isolating the specific practice that will make these things happen.

We’ve all been there…attempting to learn long lists of standards, playing an etude from start to finish over and over again, trying to transcribe an entire solo, soloing with a play-a-long and “hoping” to get better…

The irony is that practicing your big goal by itself does not help you get any closer to actually achieving that big goal.

This is exactly why you need to take a different approach…

Breaking down your goals

The key to getting from the big goal stage to the improvement stage lies in breaking down your goal in the practice room.

And this step requires a little reverse-engineering…

Think of it like this, you’re starting out with a finished product and breaking it down to see how it’s made, how it works, and the essential elements that make it tick.

Your big goal is the destination at the end of a long windy road, and your job is to find the pathway there, step by step.

Every goal that you make contains a series of smaller pieces, foundational skills, and musical concepts that contribute to the whole. All together, it’s hard to improve, but one by one it’s surprisingly achievable…

No musical skill from smallest technique to your biggest ambition is just one thing, a single task that you can or can’t do. Your goal is really a collection of smaller skills that you need to master.

And focusing on these smaller pieces is where the improvement happens….

With your goal identified, the first step is to reduce it into its essential elements, the pieces required for any person attempting performing it.

For instance, let’s take a goal that all of us have whether it’s conscious or not – to become a ‘better’ improviser.

Over time we all create this image in our mind of an ideal player, the musician that we want become, that has the best qualities of our favorite players, and can play anything with ease…

Getting to this goal is why we go into the practice room each day…but how exactly do you practice this goal of “getting better” or becoming a great player?

Do you learn lines? Memorize chord progressions? Transcribe solos? Practice patterns in all keys??

Even though our motivation is coming from the right place, the objective is just too big and undefined. From this place progress is very difficult to come by.

Time for a more focused approach

Now we’re going to take a slightly different approach to this goal. Let’s imagine that ideal player in your mind once again…

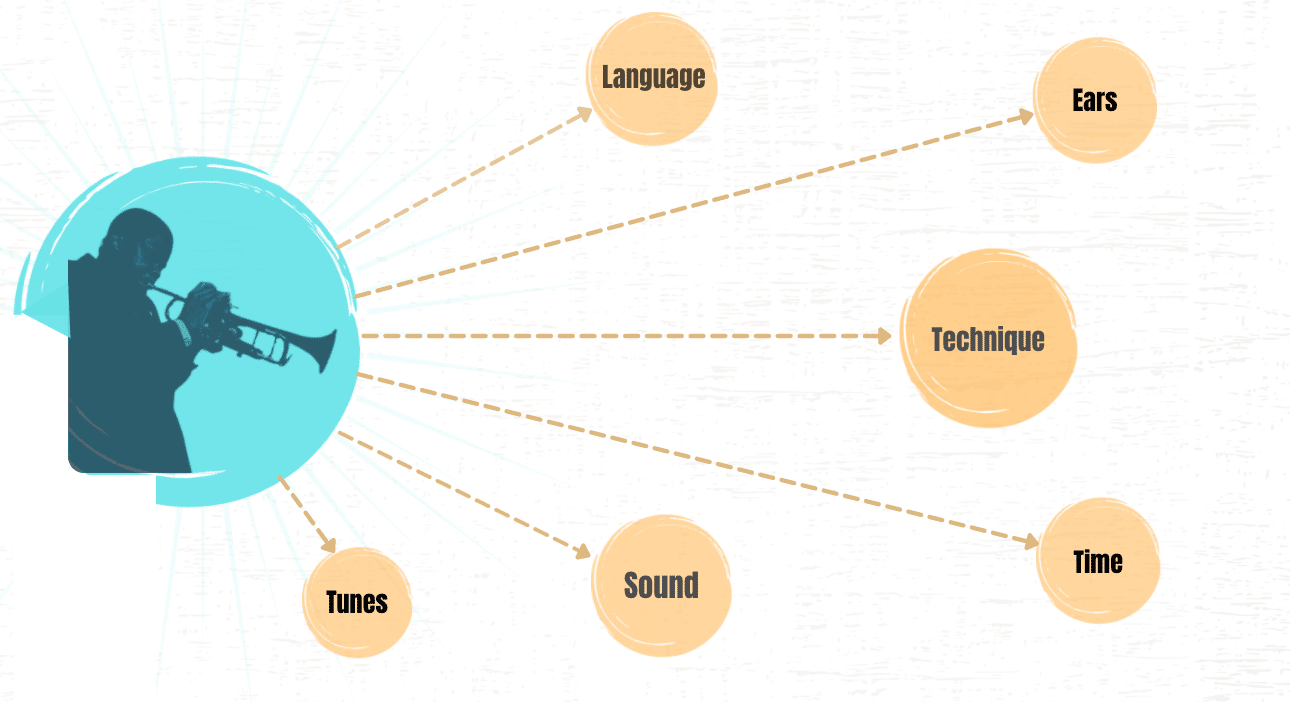

This time ask yourself this: Which specific traits and skills does this player have?

What is required of a musician that wishes to play at this level? Write a list out:

- Effortless Technique

- Know a bunch of tunes

- Learn language for every chord type

- Develop a great sound

- Master harmony and theory

- Have great Time & rhythm

These are the more specific skills that go into this “great player,” and identifying them gets you one step closer to something that you can actually practice…

But you’re not done yet, now you need to get even more specific…Each of these subcategories can be broken down even further:

Technique includes fingers, fluency in all keys, articulation, and range. Time is rhythm, swing, hearing form, and awareness of each beat and subdivision. Ears consists of hearing chord quality, intervals, chord tones, and chord progressions.

Each skill has a subset of skills and techniques, and these much more achievable in the practice room.

Now it’s time to get personal

The next step after listing these elements is figuring out which specific things you need to work on the most.

Even though many of us share the same goals as musicians, our pathway to these destinations will be different.

So let’s go back to that list of skills, what is one area that you need the most work on. Which of these essential pieces of your goal needs the most attention?

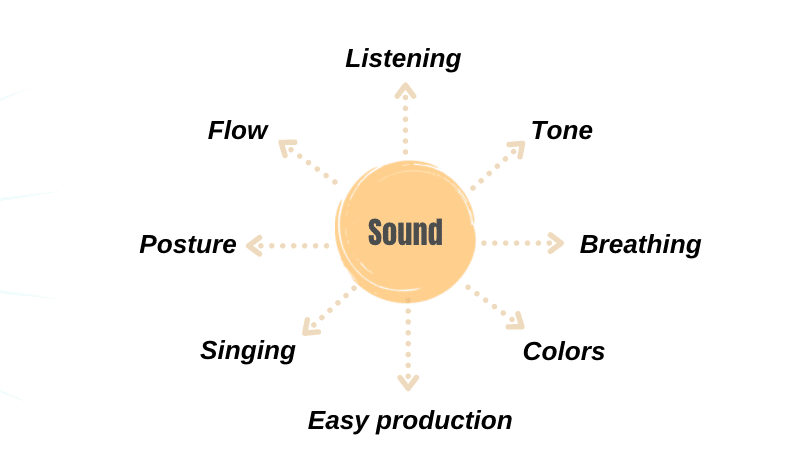

For instance you might feel confident on theory and tunes, but wish you had a better sound in your lines from low to high. But what goes into sound?

This can be broken down even further as well…

Maybe the key to improving your sound starts with focused breathing exercises, meditation, relaxation, and developing an easy and constant flow of your lines.

The focus of your practice for a time will be on effortless sound production and fluidity of sound through the registers. This is the pathway to improving one small piece of your goal, the barrier that you need to overcome to make progress.

More often than not, the thing holding you back from tangible improvement isn’t practicing the big goal itself, it’s a small technique or idea that will open the doors to progress.

The overall objective with this process is to take that huge goal with vague or unknown elements and narrow things down into specific skills and related exercises that you can focus on in the practice room.

The more specific you get the easier it will be to work on these small tasks each day as you practice. And over time this will lead to real results that you’ll notice in your playing.

Getting to the real practice

As you can see, the reality of working toward a big goal is oftentimes not exactly what you think it’s going to be.

This is why I used to wonder why I’d hear great players practicing long tones, doing slow exercises with the metronome, or sitting at the piano and working on two chords over and over again.

I was expecting fast tempos, advanced harmonies, and complicated melodic concepts…

However, what I didn’t know was that these players were doing the real practice of working toward a goal – focusing intently the things they needed to do to achieve their larger goal.

And this is the approach that you need to make if you want to start seeing results as well!

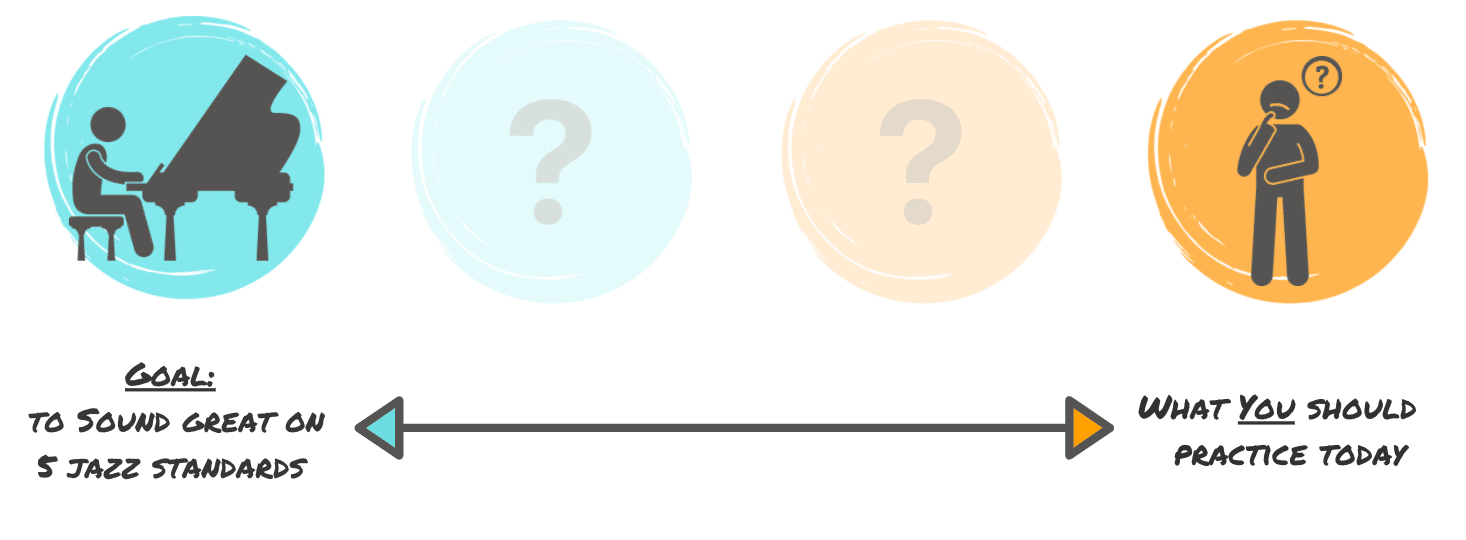

To see what I mean, let’s apply this process to the common goal of learning a list of standards that you want to perform at a high level…

For many players this goal entails memorizing each tune and playing through them over and over until some sort of progress is made. But before you grab a real book and turn on a play-a-long, think again…

Remember, memorizing the melody and chords to a bunch of tunes is just one piece of the puzzle, and knowing them doesn’t really make you sound better in your solos.

So using the same process, let’s breakdown this larger goal and focus on a single element that you can actually improve in a practice session:

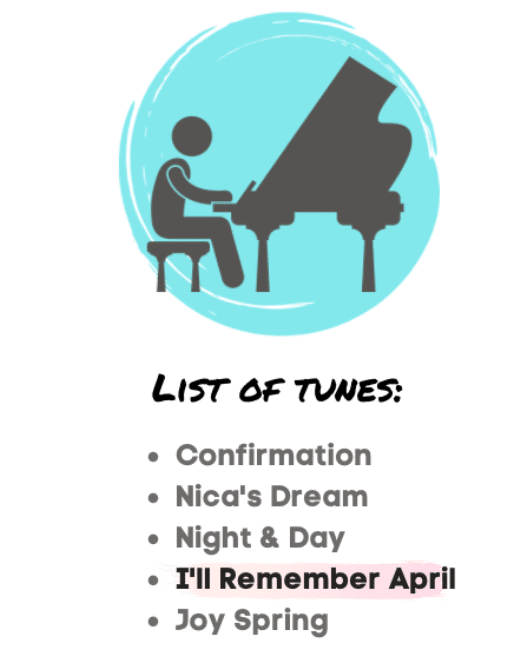

First start with the tunes you want to learn:

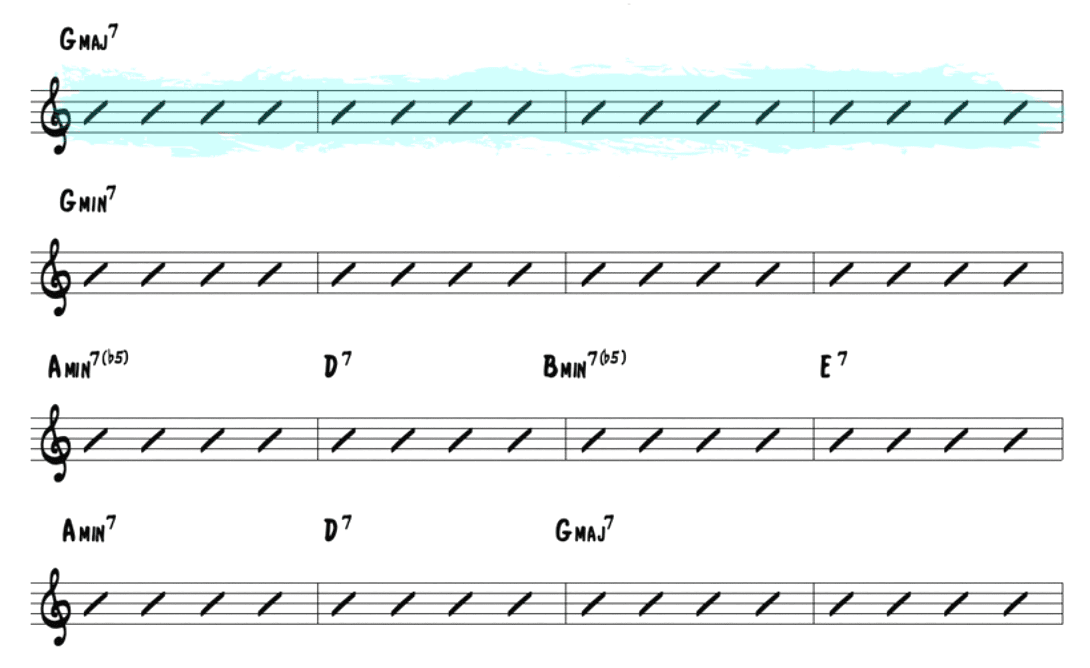

Trying to master them all at once (your big goal) is not going to be very likely in the space of a single practice session. So pick out one tune to focus on, let’s say it’s I’ll Remember April…

Now you need to break down this tune into its essential pieces. Which element of this tune do you need or want to focus on?

Maybe you want to focus on the chord progression. Ok, go even further, isolate one harmonic element of the changes, say major chords:

Now ask yourself: Can I improvise over Major chords? Do I have language and techniques to play in these situations?

Finally we’re at a place where there is a clearly defined and specific skill to focus on in the practice room – one that is manageable for a practice session.

Maybe you’ll start by figuring out what Clifford Brown is doing over the major chords in this tune…

This practice will lead to actual results when you play and gets you closer to the larger goal of sounding great on the list of tunes.

So what is your goal?

Before you start your next practice session, take a moment to reflect on the goals you have as a musician…

Pick out one goal that you have and think about the smaller pieces that make up this larger goal.

Don’t be satisfied simply saying “I want to get better” or “I need to learn this tune,” get specific and detailed. Isolate the exact skills that are involved and the areas you need the most work on.

The process we outlined above can be applied to any goal from learning a tune, to transcribing a solo, to figuring out a chord progression, to specific techniques…

If you truly want to see improvement with your musical goals you need to go that extra step that most players forget about. Give it a try and you’ll find that any goal is much more achievable that you think!