Louis Armstrong is called many things: a musical pioneer, the father of American music, the first great soloist, and the catalyst for countless creative musicians around the world…

But for many musicians today, his music can seem old hat, antiquated, and even irrelevant – I mean what can you actually learn from a bunch of old recordings made before the advent of bebop, Kind of Blue, and all the of “modern” stuff we listen to today??

The surprising answer is more (a lot more) than you think. And the truth is, you can pick any Louis Armstrong solo, any melody that he interpreted, and discover a valuable musical lesson that will help your playing.

You see all these years ago Louis Armstrong was laying the melodic and harmonic foundation for this music and for every musician that would follow. Defining how a soloist creates musical phrases, uses time & rhythm, and improvises in a melodic way.

You can’t play anything on a horn that Louis hasn’t played –I mean even modern. I love his approach to the trumpet, he never sounds bad. ~Miles Davis

This is a foundation that every great improviser following in his footsteps would learn and eventually build upon…and it’s a musical lesson that you must learn as well if you’re serious about sharpening your skills!

Sure, the recording quality might be poor and the stylistic approach might sound outdated, but Louis Armstrong’s musical genius shines through. And if you dedicate some time and attention, you’ll pick up some valuable skills along the way.

I’ll show you what I mean…

Basin St. Blues, 1928 Solo

Today we’re going to focus on a particular solo from Louis Armstrong that’s nearly one hundred-years-old. A massive amount of time in relation to the progression of modern music history.

Think about this for a moment…

The year he made this recording a little kid in Kansas City named Charlie Parker was turning 8 years old. John Coltrane and Miles Davis were the ripe old age of two, and masters like Herbie, McCoy, Freddie Hubbard, and Wayne Shorter weren’t even born yet!

Take a listen to Basin Street Blues recorded with the Hot Fives and Sevens in 1928:

At [2:06] in the recording, Armstrong begins his solo…

Let’s take a closer look at six specific techniques Louis Armstrong uses in this solo, techniques that are surprisingly relevant today…

Phrasing, Rhythm, & Melodicism

One of the most notable things you can learn from Louis Armstrong is his approach to creating melodic phrases.

The thing about listening to “Pops” is that you can’t separate the individual notes he’s playing from the larger rhythmic and musical picture he’s creating. It’s all one connected piece of his musical personality, whether it’s coming from his trumpet or his voice.

And this should be true of the way you approach improvisation as well – the point isn’t just to follow music theory rules and have technique, it’s to make music!

Let’s take a look at a couple of the ways Armstrong utilizes the concepts of phrasing, melody, and rhythm in this solo.

I) Approaching improvisation with the melody

One the first things you hear when learning to improvise is the advice “Use the melody as your guide!” The idea that you’re supposed to create an improvised phrase over a chord progression with inspiration and guidance from the written melody.

This is something that Armstrong did naturally. In fact, everything he played came from a melodic perspective, and his solo here is no exception.

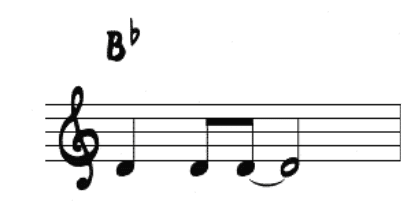

The original melody of Basin St. Blues is largely centered around a D, starting on the 3rd of the home key:

A simple melody from a harmonic perspective, one note that is sustained through the changing harmony of the tune. Now listen to how Armstrong uses this melody as the skeleton or foundation of his solo:

Starting with the framework of that recurring D, Louis expands upon this theme, creating melodic shapes, extended phrases, and rhythmically creative ideas…

Let’s take a closer look at how Armstrong achieves this, beginning with the very first measure of his solo. Here’s the original melody:

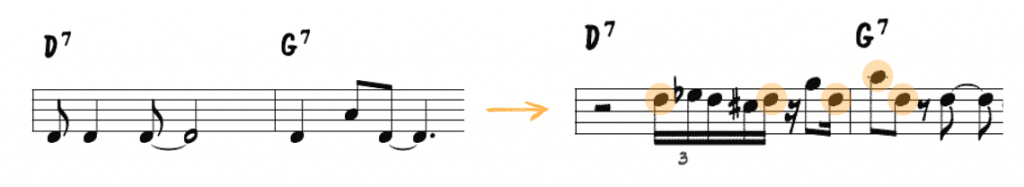

How do you improvise with this melody or get creative with just the 3rd of the chord?? Here’s what Armstrong played…

Retaining the notes of the melody, he takes a triadic approach to melodic content, adding shape and rhythmic interest to a single note.

As opposed to a theory approach, filling up the measure with notes that match the underlying chord, he creates concise musical ideas with shape, rhythm, and harmonic content.

Here’s another example where Armstrong creates moving phrases with the simplest of melodies…

In these two measures he augments the melody of the D with chromatic neighbors (Eb and C#). Notice how he also connects the D7 to the upcoming G7 chord, phrasing V7 to I, giving his line forward motion.

As you think about approaching your own solos and interpreting written melodies, use these ideas as your starting point. With a rhythmic and melodic approach you can turn even the most basic elements into moving music!

II) Rhythmic variety & phrasing

When you transcribe Armstrong’s solos and attempt write them down, you’ll immediately notice that it’s difficult to notate the rhythms! This is because his approach to time is astonishingly free and natural.

He transcends the rigid structure of the time and the chord progression of the tune to create his musical ideas. His lines and time are being created organically from a melodic and vocal place, rather than a theoretical one.

He changed the feel. It’s one thing to have your own feel, but it’s an entirely different thing to change the conception of what a quarter note feels like. I can’t think of anyone in recorded history who’s done that. And we’re still borrowing his quarter notes – the forward motion and the pulse… ~Nicholas Payton

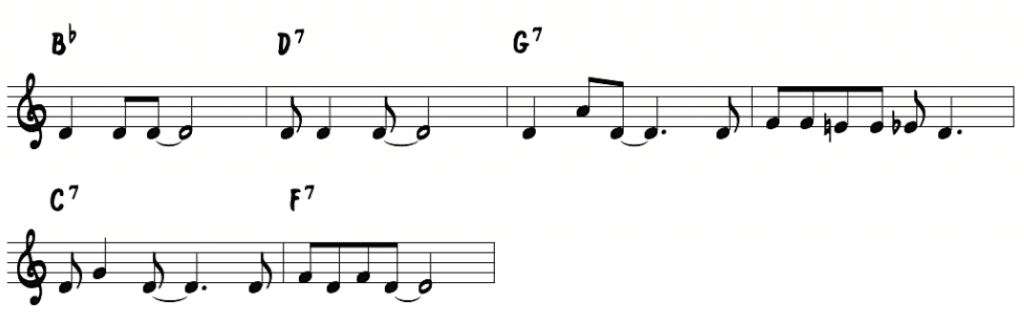

The rhythm of his phrases is just as essential as the notes he chooses to play. He’s not just stringing together 8th note lines, but improvising with the time as well. For example, take look at the first eight bars of his solo solely from a rhythmic perspective…

The sparse accompaniment is not swinging and the rhythmic backdrop is simple, straight quarter notes. All of the swing and musicality comes from Armstrong – created with the feel and rhythm of his lines.

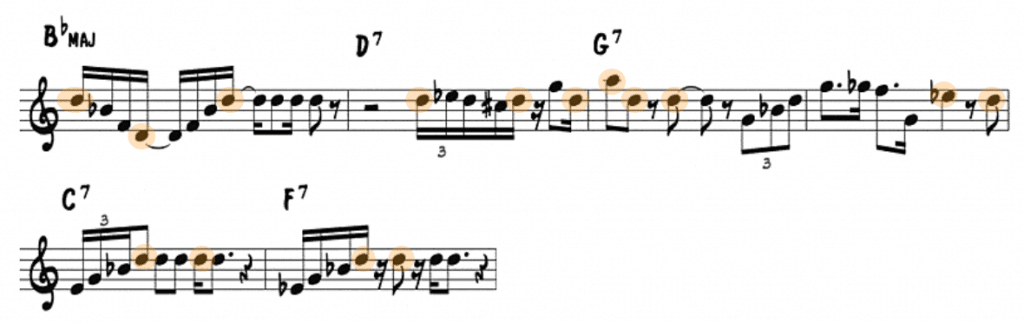

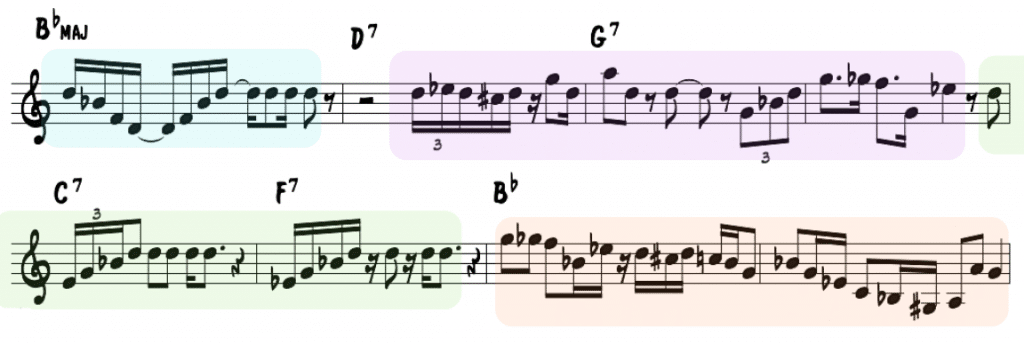

Now look at those same eight bars in terms of creating phrases with defined musical ideas and you’ll immediately see the importance of phrasing in creating a strong solo:

You can clearly hear four succinct musical ideas, and notice how these phrases stretch over the bar line. Two pieces of Major language on the Bb chords, a phrase with harmonic tension over D7 to G7, and a melodic sequence on the C7 to F7 chords.

This melodic approach to phrasing is something that all great improvisers do. The great Charlie Parker comes to mind, especially in the way he approaches his solo on this 1942 version of Cherokee or as he does to the melody of All the Things You Are, shown below:

You hear the same rhythmic freedom and approach to time and phrasing as Louis’ solo, and the same should be true of your musical approach.

Try to incorporate these three techniques in your own solos: utilizing the original melodic framework, incorporating rhythmic variety, and applying melodic phrasing.

Emphasizing Upper Structures of chords

When you think of jazz from the first few decades of the 1900’s, you probably don’t think of upper structures or altering notes on dominant chords.

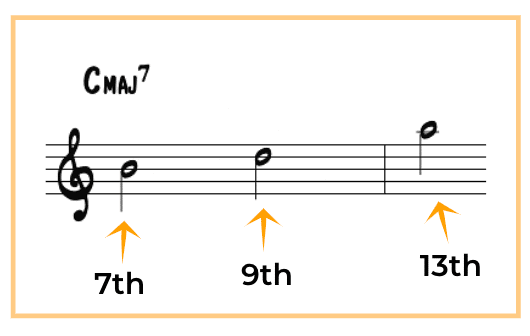

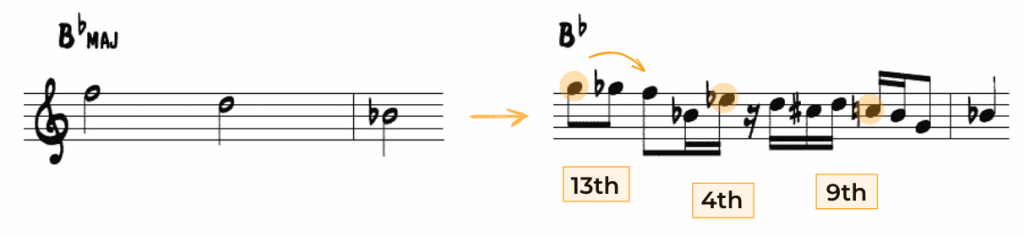

I’m talking about emphasizing the 7ths, 9ths, and 13ths of Major and V7 chords:

But if you listen closely to Louis Armstrong, you’ll hear these over and over again…

III) Utilizing the Major 7th, 9th, and 13ths

For instance, listen to this phrase he plays in the second half of his solo:

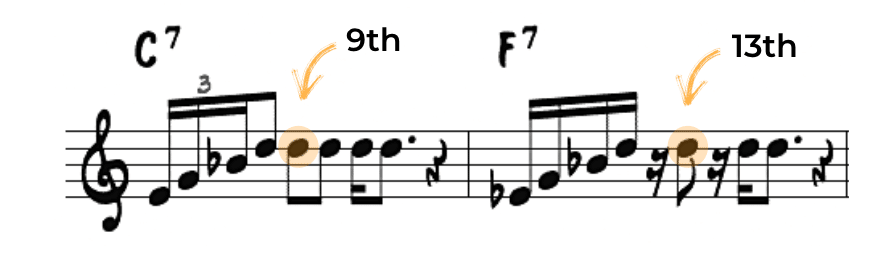

In this line he aims for the Major 7th on the Bb chord and emphasizes the 9th on V7 chord. Or check out this melodic sequence he plays below, aiming for the 9th of C7 and the 13th of F7:

In this sequence, he also approaches the V7 chords with arpeggiation from the upper reaches of the chord, moving from the 3rd to 9th of C7 and from the b7 to 13th of F7.

Strive to make these upper structures accessible tools in your approach soloing – aim for those Major 7ths, 9ths and 13ths on Major and dominant chords!

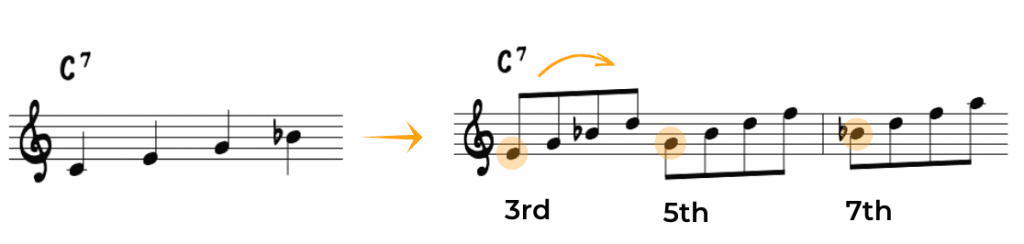

And remember, you don’t have to play every chord in root position or approach it from the root. As Louis does, try approaching or arpeggiating chords from the 3rd, 5th, or even 7th…

Chromaticism, enclosure, & ornamentation

One common thread among the greatest of improvisers is their ability to create melodies with the most basic elements of music. This is true of musicians like Louis Armstrong, Bird, and Miles, all the way to the players we look up to today.

In the right hands, something as simple as a chord tone or a triad can be transformed into a compelling musical statement.

This isn’t some ingrained talent or hidden skill however, there are some simple techniques that you can use in your playing to achieve this. And this is something that Louis Armstrong was doing in the 1920’s…

IV) Expanding on triads with chromaticism and enclosure

One device that Armstrong uses in this solo to create melody with simple triads is by incorporating chromaticism, enclosure, and neighboring tones.

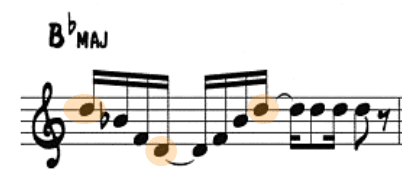

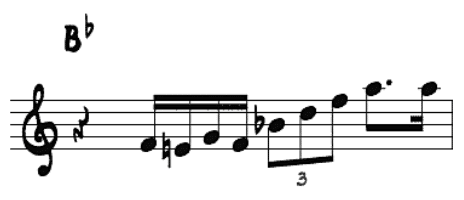

Let’s check out a few examples, starting with this phrase from the second half of his solo:

Using a simple Bb major triad, he utilizes neighboring tones to enclose the 5th and lands on the Major 7th of the chord.

Also notice how he employs three different rhythms in the space of one measure – 16ths, triplets, and dotted 8th 16th. Combined with enclosure and the color of the Major 7th, this a simple triad becomes an interesting musical statement.

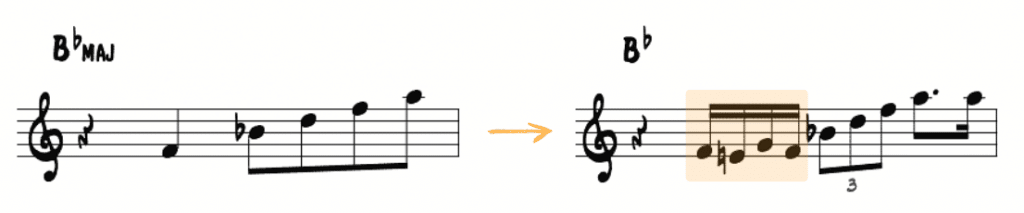

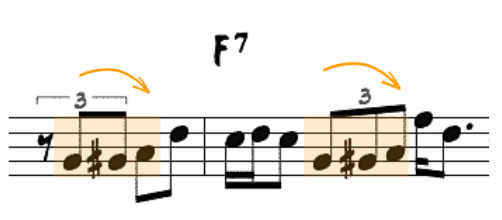

Here’s another example of the same technique, again with a Bb triad:

He augments the traditional harmonic and melodic approach to a Bb Major chord by incorporating the 13th, 4th, and 9th along with chromatic movement to emphasize the strong chord tones:

Expanding the harmonic possibilities of a static major chord with extended chord tones and creating interest rhythmically. Finally, check out he applies this same idea to a V7 chord:

In this musical statement he approaches the 3rd of the chord (A) chromatically from the 9th and emphasizes the 13th (D):

The foundation and goal notes of each statement is based around the chord tones of triad. However, with the simple addition of some chromaticism, neighboring tones, and enclosure they become much more musically compelling.

V7 to I Techniques

Mastering the V7 to I progression is essential for any improviser. In fact, it’s one of the most basic building blocks of functional harmony and an integral part of nearly every jazz standard.

The more tools you have for navigating this chord movement the better. And like most things musical, studying Louis Armstrong is a great place to start…

V) Emphasizing the b9 and b13 (#5) on V7 chords

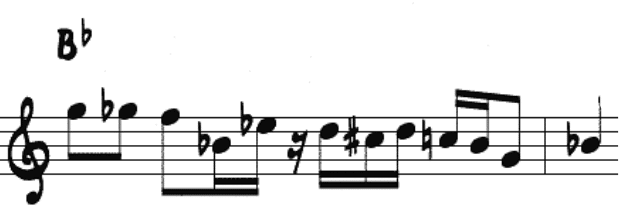

On almost every dominant chord in this solo, Armstrong uses chromaticism and an alteration before resolving to the next chord – specifically, he utilizes the b9 and b13.

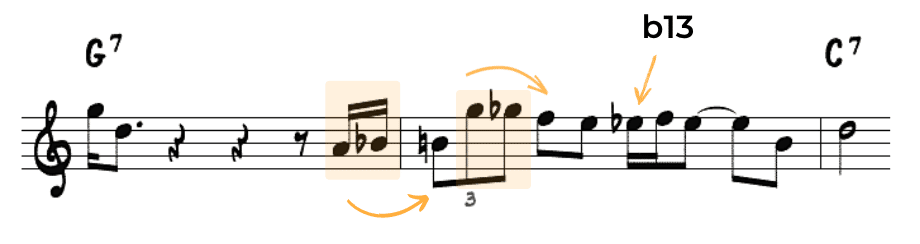

To see what I mean, take a listen to this line that he plays over a G7 chord moving to C7:

Here he uses chromatic approach notes to the 3rd and 7th of the chord and emphasizes the b13 (#5) to add harmonic tension that resolves to the 9th of C7:

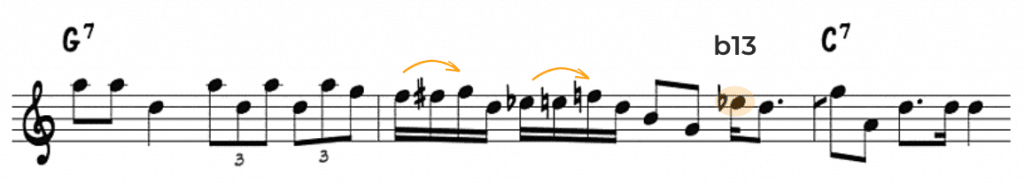

Later on in the solo over the same chords (G7 to C7) he applies the same technique…

Again using chromaticism to land on strong chord tones and emphasizing the b13 on the V7 chord that resolves to the 9th of the next chord.

Another technique that Armstrong applies to dominant chords in this solo is using the b9 and major 7 to enclose the root:

He uses the same technique later on in the solo, enclosing the root again with the b9 and major 7:

There are many techniques for altering V7 chords out there, make sure you master these two from Louis Armstrong first!

Implying ii-V’s over existing chords

It might seem like inserting or implying ii-Vs into a progression is solely a bebop technique, but once again, Louis Armstrong was doing it in the 1920’s…

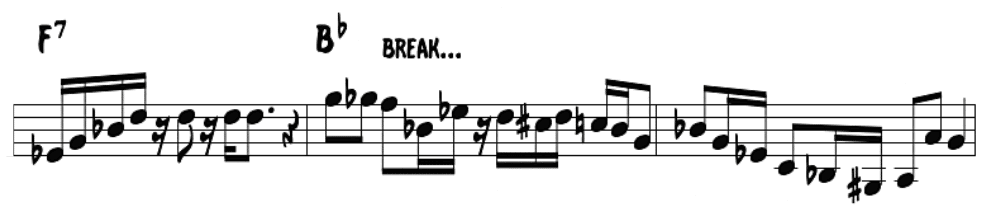

Let’s take a listen to the first solo break in his solo:

VI) Implying the related ii-V7 over a Major chord

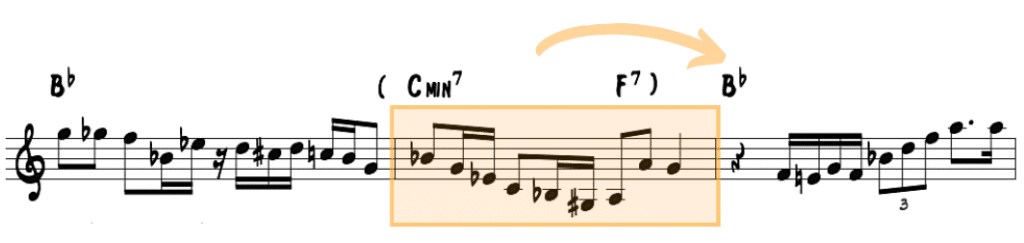

In the 7th and 8th bars of his solo, Armstrong plays this line:

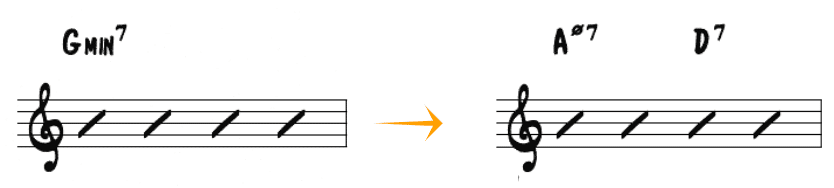

In the last bar over the break, he is implying a ii-V progression (C- F7) that resolves to the I (Bb)…

He achieves this melodically by playing a descending C-7 arpeggio and enclosing the 3rd of F7.

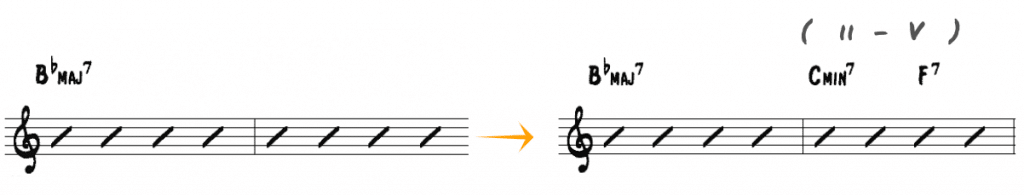

You can use this technique to create melodic and harmonic motion over static chords. Rather than playing in Bb for two measures, Armstrong creates forward motion (implied ii-V progression) that leads into the upcoming I chord:

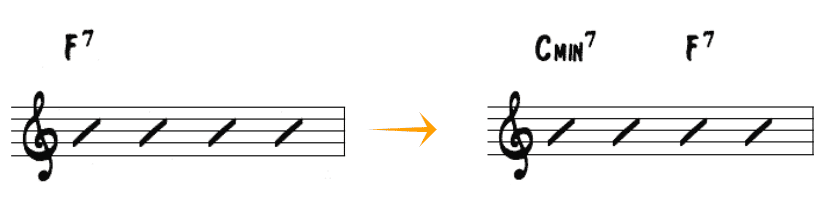

In addition to Major chords, you can also use this technique on dominant chords:

…or even minor chords:

Once you understand that concept Then the next step is having ii-V language to play over these spots.

Musicality is timeless…

Sure, the solo is over 90-years-old. Yes, the recording quality leaves something to be desired. And I know, the style isn’t what you’d call modern by any stretch of the imagination.

…but hidden inside this recording are a collection of musical secrets that can help you solve your musical problems. Right there for the taking for those that are willing to put in the time and effort to master them!

Six musical techniques that you can begin using in your solos TODAY. Six techniques that you can apply to jazz standards, modern tunes, or your own compositions. Six musical truths that are timeless…