Practicing lines in all keys is a must, but it’s not that easy or even clear why it’s so important in the first place. Many years ago, I remember trying to take a ii V line through all keys on the saxophone and it was really difficult. I’ve even had several decent players tell me they struggle with this skill.

After years of practice, it’s become effortless and it’s just second nature for me to take lines through all the keys.

So for today, here are the tricks that I’ve picked up over the years that will help you think and play in all keys.

Why play lines in all keys?

There are many benefits to playing lines in all keys. The most obvious one is that it gives you material for every key.

But there are a lot more benefits to it than that…

Playing lines in all keys improves your technical facility

Practicing every range and fingering on your instrument yields better technique, but, often we hang out in one register and fallback on our finger habits. By taking lines through all keys, we’re forced to hit every part of our instrument and work through tricky fingerings that we’d otherwise ignore.

Playing lines in all keys gives you mental dexterity

When you play lines in all keys, do not write them out. Do them in your mind. I will reiterate this point again and again because it’s so important. You must transpose the line in your mind. And by doing so you will stretch your mind in exactly the right way it needs to be stretched for improvisation. More on this later…

Playing lines in all keys is good for your ear

When you move a line through all keys, your ear is constantly listening and checking to make sure you execute it correctly in each new key. By doing so, your training your ear to pay attention to intervals, melodies, and how chord structures.

Playing lines in all keys helps you improvise smoother lines

It’s difficult to explain, but through the process of taking lines through all keys, as it becomes to get easier you’ll find yourself improvising smoother lines, making smoother voice leading from chord to chord and improving your general musical flow.

Are you convinced yet?

Now let’s get started with how to make it happen…

Forget solfage. Think numbers.

You’re not Julie f*&%#*ing Andrews!

Forget solfage.

Think in numbers. Not only is it easier, it’s far superior.

Thinking in numbers makes it easy to transpose a line into all keys and strengthens your ear-mind-finger relationship for every key.

By thinking in numbers, you’re simultaneously connecting your fingers, your ear, and your mind to the harmony.

That’s power.

For example, if I know I’m playing “3” over C major, my fingers know they’re on the 3rd of a major chord, my ear hears the note I’m playing as the 3rd of a major chord (assuming your ear knows what the third sounds like on a major chord), and my mind knows intellectually that I’m on the 3rd of a major chord.

And when you begin to play a lot of altered chord tones, thinking in numbers helps tremendously because you have these nice labels you can throw around with ease: b9, #9, b5, #5. It makes it easy.

Another important point is to make sure you’re thinking in numbers which correspond to the chord you’re playing over. Sounds like common sense, but it’s not.

I’ve seen many students thinking in numbers over a parent key or over a substituted chord.

Now the latter, is more acceptable, even though it can still be dangerous.

It’s dangerous when you don’t understand how the substitution relates to the harmony going on because without this knowledge, you won’t resolve the substitution correctly or hear the substitution in your mind, which makes for a very weak substitution—the keys to a strong substitution are hearing it in your mind and a clear resolution if you’re resolving.

So, until it’s solid, try to think about the numbers in relation to the chord that’s going on and that will save you from fumbling in any situation.

Break the line up into several pieces

Now this doesn’t go for really really short lines, but most lines can be broken up into multiple lines.

This helps you a multitude of ways.

First, it gives you more material because it’s much easier to use smaller lines than long lines.

I hear people all the time trying to fit these long lines they’ve transcribed into their solos. It doesn’t sound natural at all.

But if you break up the line into small pieces, say a measure or so, then you now have a workable melodic unit that you can use.

Actually, this is another big tip that a lot of people miss. When you transcribe a line more than a measure long, you may feel the need to keep it whole, like you’re not allowed to break it up or extract parts out, or that you shouldn’t.

I remember feeling that at some point years ago. That these lines belonged to a master player and when I took them, I should keep them intact because that’s how the line was played.

Well, this attitude will shortchange you. Why? Because even the improviser was piecing that material together!

Yes, even they were not inserting these whole big blocks of lines, so why keep it like that?

Breaking the line up into smaller pieces is essential. It will help you play in all keys, it will give you more material as we talked about, and it will teach you how to begin the line at different places.

Who says you have to start the line at the beginning or use all of it?

To get the most out of a transcribed line, make sure to break it up into several pieces and practice each individually in all keys.

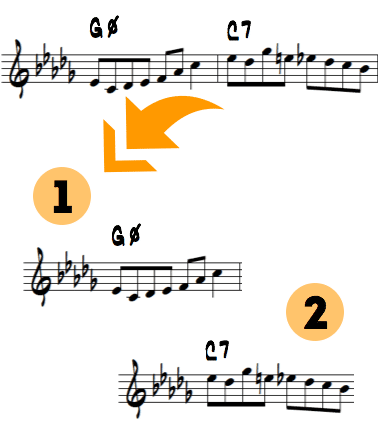

Take this Bill Evans line for instance, from Woody’N You at 1:42

Here it is slowed down:

And here’s what we can do with it…

See how we broke it up into two lines? Now we have a half diminished line and a dominant 7 line that we can practice in all keys. We can always link them back up later if we want to as well.

Start with an easy key, then add one at a time

When you first start to take a line through all the keys, tackle one instead of 12.

Begin in an easy key with a metronome on 2 and 4 at a slow to medium tempo. Gradually increase the tempo until you’re playing at least sixteenth notes at 104 bpm.

Another trick you might do is between each time you play the line or every few times you play it, don’t play it on your instrument, but instead visualize it.

The secret to playing in all keys easily is being able to visualize it in your mind effortlessly in all keys. So, remember: visualize, play, visualize, play…

The goal is not merely to take it through all keys, it’s to master it in all keys! Like I say all the time, if you practice something short of mastery, it’s time wasted. This is black and white.

There’s no in-between.

Jazz improvisation is like being in the heat of battle. Only what you really know comes out.

Once you master it in one key, add a second key by moving down a half-step. Now master it in that key.

Visualize, play, visualize, play…

Then move back to your original key, play it once and then play your new key once. And then repeat these two keys together like this for a few minutes.

Next, add a third key.

Visualize, play, visualize, play…

And once this key is mastered, do the same thing you did before. Add it to the other two, play them all together, then add another key.

Keep doing this until you’ve added all the keys.

Play it in various root movements and directions

Playing a line in various root movement and directions is where the fun really begins.

As I said before, Do not write the line out!

You will do the entire transposition in your mind. Yes, the entire transposition, meaning you cannot even look at a series of root positions on a page to help you out.

Everything will be in your mind. By forcing yourself to practice this way, you’re increasing your musical memory and flexing the muscle you actually use when you improvise.

When you improvise, you’re aware of the chord you’re playing over, the next chord coming up, the form, what you’re playing and how it relates to the harmony, where you’re taking your solo in terms of development, what the rest of the band is doing, and more…

How is this extreme amount of multitasking possible?

It’s only possible if you constantly force yourself to practice in a way that makes you multitask.

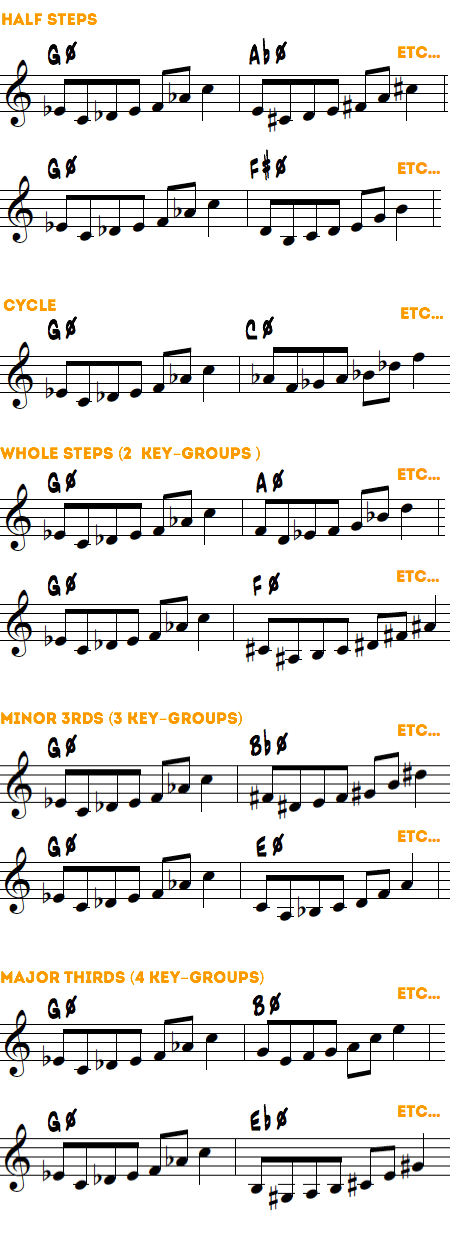

Practicing lines in various root movements does this. Here are the essential root movements to practice:

- Half steps up

- Half steps down

- Whole steps up (2 key-groups, 6 keys each)

- Whole steps down (2 key-groups, 6 keys each)

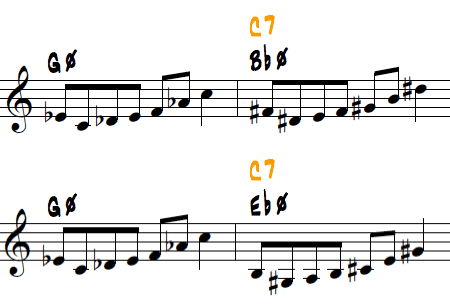

- Minor 3rds up (3 key-groups, 4 keys each)

- Minor 3rds down (3 key-groups, 4 keys each)

- Major 3rds up (4 key-groups, 3 keys each)

- Major 3rds down (4 key-groups, 3 keys each)

- Cycle movement (descending perfect 5ths/ascending perfect 4ths)

When I specify a “Key-group” that means you have groups of several keys to practice. For example, if you play a line up and down in whole steps, you’re only hitting 6 keys, so, you have to hit the other key-group containing the other 6 keys.

So, if I were taking a line through all keys in various root movements and directions, it would look like this–but remember…you would do ALL of this in your mind without writing the lines out or looking at the chord changes of the root movements:

When we’re taking a line through all keys in various root movements and directions, we have to think about:

- What chord am I on?

- What chord is next?

- Am I playing the right chord tones in the line for the current harmony?

Sounds a bit similar to the process we just take about, huh?

That’s right. It’s very similar to the mental process going on in the background during improvisation that needs to be so effortless it doesn’t hinder our ability to improvise.

That’s why this exercise is so valuable. It’s one of the major ways that we can work on this mental process and make it effortless so we can concentrate on making music instead of the details of what’s going on.

And, practicing this way is when things really come together with a line. It’s where you begin to gain flexibility with it, improve your technique, work on your ear, and even find new ways of applying the line.

For instance, maybe you’re practicing that Bill Evans line in minor and major thirds and you hear a transposition that sounds cool to your ear. And then you think, What if I play it over a minor ii V?

Sure, the B natural doesn’t belong to the C7 chord, but it still sounds great because of the strength of the line. Let your ear be your guide. And, if it’s not to you’re liking simply adjust the transposed line so it lays over the target chord to you’re liking.

As you can see, practicing a line in various root movements and directions is so good for your musical mind, fingers, and ears.

It’s tricky though.

Just as you focused on one key at a time when learning a line in all keys, focus on one root movement at a time.

Begin with half steps up and down and Cycle movement, in either order. Either one of these root movements gets you accustom to the line in all keys, which is a great way to start.

Once you’ve mastered half steps in both directions and cycle movement, move to whole steps in both directions. Make sure to practice both groups of whole steps—if you play a line in whole steps you’re only hitting six of the keys, so you have to also hit the group up a half step.

Then, move to minor thirds in both directions, all four groups, followed by major thirds in all directions, all three groups.

I always used to wonder whether I should practice more root movements than this because people used to tell me, all keys, all root movements, both directions.

You can practice them further if you like, playing the line in tritones, perfect fifth, etc…

But the root movements you’ll get the most out of and the ones you want to be sure to practice are the ones we talked about.

It’s time to start practicing lines in all keys

Playing lines in all keys is an absolute must for any jazz musician who wants to get beyond their current level.

It’s difficult, but I promise you it becomes very easy the more you practice it.

Make sure you are thinking in numbers. Every time you learn a line, go through it in your mind and name each note in relation to the harmony. Actually say, “13567#9” or whatever the line may be.

Numbers are a quick way to connect your ear, mind, and fingers. By doing so you’ll make playing something in all keys much easier and never become “key dependent.” In other words, you always want to bee key independent, meaning you understand the relationships going on so much that the key doesn’t affect you.

Break the line up into as many pieces as you like. This is how the line actually becomes useful.

You can’t insert a long line and it’s very difficult to improvise with long blocks of material.

When you a break a line up, you unleash it’s possibilities.

Master the line in one key before adding more. Instead of going straight to all 12, just pick one.

True mastery of the line in all keys will give you the facility you need to take it through all keys in various root movements. So, once you’ve mastered the line in all keys with either half step or cycle root movement, then…

Practice the line in various root movements and directions. Everything comes together and you gain a true flexibility with the line, stretching your ear and your mind to engage in a mental process similar to that of improvisation.

Now you’re ready to take lines through all keys! Happy practicing.