On this site we’ve talked about transcribing numerous times. From the reasons you should be transcribing solos to the best method of transcription…even to the different definitions of transcription for jazz musicians. Knowing why you’re transcribing and how to do it are vital to improving as an improviser.

The most important aspect of the transcription process, however, is what you do with that language once you’ve figured out the notes by ear.

There is an attitude among some musicians and educators that you must transcribe as many solos as possible in order to improve. More is better. If you’ve transcribed two solos, you need to do ten; if you’ve transcribed ten, you need to hurry up, get your act together and do twenty.

When you get down to it, great leaps in knowledge can truly be accomplished through one transcription. Simply transcribing as many solos as you can and quickly moving on to the next won’t guarantee success and is likely overwhelm and frustrate you. Sure, you are transcribing a lot, but are you absorbing any of the language that you’re pulling from the records?

Less is more

It’s a simple idea: If you need language (ii-V’s, longer lines, etc.), you need to transcribe solos, but the belief that you’ll dramatically improve by transcribing a ton of solos is misguided. To see improvement, you actually need to develop the language you’re transcribing, not just mechanically figuring out notes and moving on to the next solo.

The transcription process is not something that is started and finished in one sitting or even in a few days. In order to develop the language you’ve picked up from the records, you need to spend weeks and months with it for it to become a part of your day to day musical conception. After you initially get the notes, articulation, and feel by ear, you need to transfer this language to all twelve keys to make it a concrete part of your playing.

The way to achieve this is not by rushing from one solo to the next, but to focus intently on one solo for an extended period of time. By absorbing every aspect of a single solo, you’ll make more progress than cramming information in as fast as you can. In other words, when you take on less, but strive to master it, you will ultimately learn more.

One solo = limitless language

The crucial difference here lies in your mindset as you sit down to learn a solo. Are you transcribing to get licks or are you transcribing to acquire lasting language? In our minds, the difference between licks and language can seem small and inconsequential. However, when it comes to transcribing, your approach can mean the difference between only making a minuscule step forward and ultimately seeing a vast improvement in your playing.

When you approach a transcription with the goal of acquiring language, there is actually enough material in one great solo for years of work. Enough harmonic, melodic, and rhythmic information to completely change your level of improvisation and harmonic perception.

How is this possible?

Well, you can probably get all the notes down in a few days to a week depending on the solo, but contrary to what most people think, your work is not done there.

Here’s where it gets interesting. After you’ve figured out the lines and phrases by ear, isolate lines over every ii-V progression, every turn-around, every major sound, every minor ii-V, every double-time line, every altered dominant chord, etc. Take every single piece of language or device that you like and study it, absorb it, and completely ingrain it into your playing through repetition.

Start with one chorus

The lines that you chose to make a part of your language can be multiple measures long or can even be as short as two beats. As long as you take the time to develop that language, you’ll see immediate progress. Here I’ll take you through the process of extracting language from a solo, to make it easier start by transcribing one chorus.

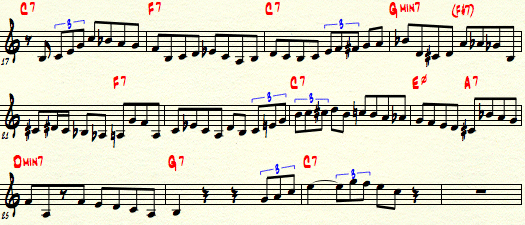

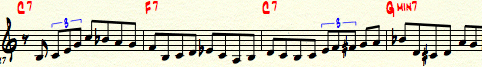

For example, imagine you’ve transcribed this chorus of Parker playing over a blues (0:47 sec in the video):

Using this chorus as a starting point, there are examples of language to use over major chords, ii-V’s, minor ii-V’s, and blues all within the space of 12 bars. Below, I’ve isolated some of Parker’s lines from his blues chorus that are great examples of language to be developed in all twelve keys:

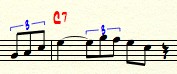

Major Language:

Learn in all twelve keys with a metronome on beats two and four starting at quarter=60, then slowly increase the speed.

Learn in all twelve keys with a metronome on beats two and four starting at quarter=60, then slowly increase the speed.

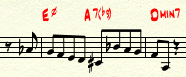

ii – V7 Language:

Learn in all twelve keys with a metronome on beats two and four starting at quarter=60, then slowly increase the speed.

Minor ii-V7 Language:

Learn in all twelve keys with a metronome on beats two and four starting at quarter=60, then slowly increase the speed.

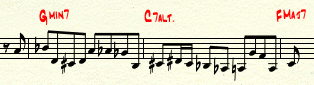

Lines over the first four bars of a blues:

Learn in all twelve keys with a metronome on beats two and four starting at quarter=60, then slowly increase the speed.

Now pick just one of these lines that you’ve transcribed and spend a week taking it through every key. Start slowly and gradually increase the tempo until it’s up to speed. Your goal is to own this line.

Practicing and incorporating this language

After you have the line up to speed and are fluent with it in all twelve keys, it’s time to start incorporating this line into your improvising. To do this, I loop a section of a recording (using transcribe) with the same chord changes as the line. For example if I transcribed a two bar minor ii-V line, I loop two bar minor ii-V on the recording and play along with the record.

Next, I will transpose the loop through all the keys until I’m equally comfortable in all of them. This is also a good time to increase the tempo of the loop and to focus on articulation. Work on hearing each note of the line as it relates to the chords and even sing the line to ingrain it into your ears.

When that feels good, I find a tune that has a the progression I’m focusing on, in this case minor ii-V, and I improvise over the tune using the minor ii-V line as a starting point every time I reach that progression. For the Parker solo above, I would loop a blues progression and lay for the minor ii-V in the eighth bar, using the minor ii-V I transcribed as a basis for improvisation.

Combine and alter lines to create new language

As you begin to master these lines and techniques, you’ll find yourself longing for variety and will eventually want to incorporate some of your own ideas into the mix. Add some rhythmic or harmonic variation to these lines to make them interesting and unique. One way to do this is to combine aspects of the line with other pieces of language or techniques you’re working on.

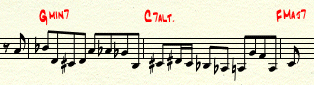

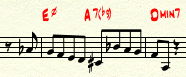

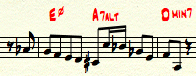

For instance in the solo above, the minor ii-V7 Bird uses is pretty standard:

You can make it more interesting by using the same alteration (#9, b9) of the C7 and the chromatic enclosure of the 3rd of the I chord he uses in the 5th bar:

The result is a new line that is more interesting harmonically and rhythmically:

Now you have a new minor ii-V…Learn it in all twelve keys with a metronome on beats two and four starting at quarter=60, then slowly increase the speed.

Even with twelve measures of a solo that you’ve transcribed, you can continually create new language, as shown above, through combination and alteration; this is the key that will give you infinite options in your playing.

Change your approach, change your playing

By using this process for every line that you transcribe, you will quickly end up with a huge amount of information at your disposal. The five example lines above from Parker’s solo were just from twelve bars of music. Multiply that by every chorus he played and the twelve keys that you’ll put every line in and you can easily see how you’ll end up with limitless language from just one solo.

At first, it may seem like you’re falling behind or moving too slowly by taking this much time for one transcription, but keep in mind that you are in fact making great strides ahead with tangible results. Instead of getting a lick for one tune or key, you are improving your overall level of musicianship.

Through this process, you’re getting ii-V’s in every key, minor ii-V’s in every key, major and minor in every key, and even developing your own language in all keys. Skills that usually take years of work can be achieved in relatively short amounts of time through intense focus.

Whether you’ve transcribed numerous solos, have attempted a few, or have yet to transcribe any, it’s a good time to start anew. For your next solo transcription, try to adjust your mindset about the goal of the transcription process. Work to acquire lasting language, style, swinging articulation, and improved technique instead of just stealing notes. By taking the time and focusing on small ideas, you will make surprising improvements in your level of improvisation.