The Chord-scale system has become the most established and widespread method for teaching jazz improvisation…And it’s no mystery why. So often, scales—more specifically the modes of the major and melodic minor scales—get passed-off as the most important aspect of learning to improvise.

It’s as if by magic, you learn a couple scales and their modes, and you’re playing jazz!

Scales and modes, are NOT the secret to learning to improvise. They are important, but don’t fall into the trap that so many do, thinking that they are the system that will give you improvisational freedom— they’re nothing more than a starting place.

The modes are the equivalent to learning your times-tables when you’re learning how to multiply.

Recall back to when you learned the basics of math. Remember how your teacher made you memorize the times-tables and drill the information until you didn’t have to think about it anymore?

That’s exactly what you want to do with ALL scale and chord knowledge. Just like the times-tables, you must internalize the information and move far beyond it. Otherwise, you’ll always wonder why your playing still doesn’t sound authentic, like you’re speaking the jazz language, because despite what you may think or have been told, scales are not the language of jazz.

Scales and modes fit into an overarching melodic and harmonic framework that help you to conceptualize melody and harmony in any genre of music. This framework allows you to intellectually understand how specific notes relate to a given chord in terms of consonance and dissonance.

But this framework has huge traps that are easy to get caught in…

Now, a lot of people have explained the Chord-scale system, how to apply the scales, and how to practice them. But what I really want to share with you, and what we’ll explore, is the major problems you’ll encounter with the Chord-scale system and exactly how to remedy them.

What are modes?

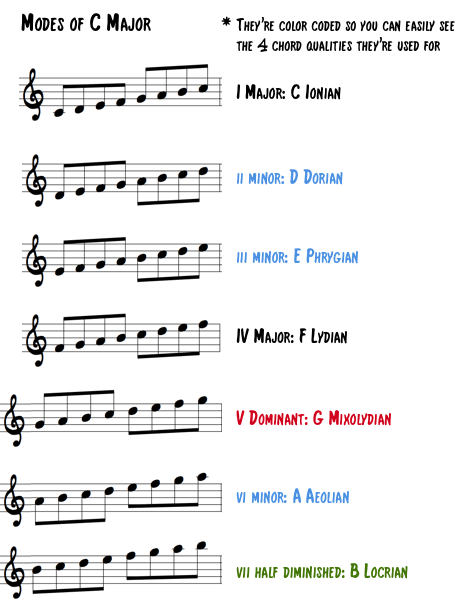

Let’s take a look at the major modes. The major modes are the 7 modes of the major scale. When you begin the scale on each different scale degree, it creates a different mode. Here are the modes of C Major:

Thinking “modally” has become extremely popular for anyone wishing to play jazz. Chances are, whenever you first picked up an improvisation book or went to a course, the first thing you were introduced to was the major modes and how they apply to chords.

But why?

Why has modal thinking become so popular?

The idea of applying a particular scale-choice, or mode, to each chord is not new, but has become the way to teach improvisation. From Wikipedia:

The chord-scale system is a method of matching, from a list of possible chords, a list of possible scales. The system has been widely used since the 1970s and is generally accepted in the jazz world today. The system is an example of the difference between the treatment of dissonance in jazz and classical harmony: Classical treats all notes that don’t belong to the chord…as potential dissonances to be resolved…Non-classical harmony just tells you which note in the scale to avoid…meaning that all the others are okay.

Because of this system, musicians can begin to improvise with very little harmonic knowledge— they have no deep knowledge of each chord, chord-tone, or the chord progression —and start to play “not wrong” notes, nearly right away.

Essentially, learning to use the Chord-scale system significantly reduces the barrier to entry of jazz improvisation.

Sounds like a great thing, right?

In some sense, it is, especially when you’re a complete beginner because it feels great to play notes that don’t clash with the chords behind you.

However, it doesn’t take long for you to realize that there are some serious issues with this way of thinking, but before we get into those, let’s look at how modal thinking can help us.

How do scales and modes help us?

The Chord-scale system has a significant purpose.

When you start anything, you have to start somewhere.

And when you learn to improvise, creating melodies over chord progressions in a seemingly spontaneous way, where do you begin?

How do you go from not knowing what a chord is, to playing beautiful melodies over chords?

Well, you have to give your brain a metal starting place to make sense of all the chord symbols that are going on…

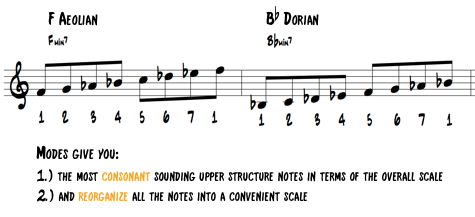

Enter the Chord-Scale system. This tool gives you primarily two things:

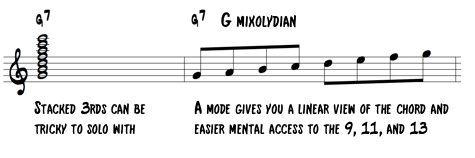

1.) How to think linearly over harmony and use the upper chord-tones – When you first learn about chords, it can be tricky to improvise melodies because your concept of a chord is simply stacked 3rds. Knowing a scale for a chord helps you view the chord in a linear fashion and helps you learn the upper parts of the chord in an integrated way.

2.) A beginning mental-model for harmony and melody – When you see/hear a chord, it’s advantageous to know what notes “work” over the chord. Knowing a scale for a chord gives you a very broad understanding of this. (Notice I say “broad” because this broad way of thinking by using the Chord-Scale system is exactly what gets us into trouble, which we’ll talk about later)

With these two things, the Chord-scale system pushes you immediately onto your path of jazz improvisation. You can be up and running in a weekend!

And that’s great news because it gets you started quickly…

But unfortunately, as time goes by, the problems this system creates for you accumulate and can leave you feeling helpless about your success as an improviser.

How the Chord-scale system has failed you

As you can see, scales and modes can be truly beneficial to your development as a musician, especially when you’re first starting out, but unless you’ve taken it upon yourself to expand your knowledge beyond the system, you’ll suffer from some severe problems.

The Chord-scale system has several prominent short-comings:

- It glosses over the relationship between chord function, modes, consonance/dissonance, and upper structure chord-tones

- It promotes “shortcut” thinking rather than a deep understanding of chords, progressions, and chord-tones

- It allows a musician to not understand chords mentally and aurally

- It causes musicians to think in terms of many scale choices

- It puts a mental divide between linear and vertical thinking

- It suggests that improvisation is merely mixing up notes of a scale

No system is perfect and the key is to figure out where the system works and where it fails.

By addressing each one of these issues one at a time and working on them, you’ll make the Chord-scale system work for you instead of against you.

Step #1: Understand the relationship between chord function, modes, consonance/dissonance, and upper structure chord-tones

How are all these related?

Every chord functions a particular way within a progression. Based on this function, the upper structure chord-tones (9, 11, and 13) will sound either more or less consonant/dissonant than their altered counterparts in terms of the overall scale. Let me explain…

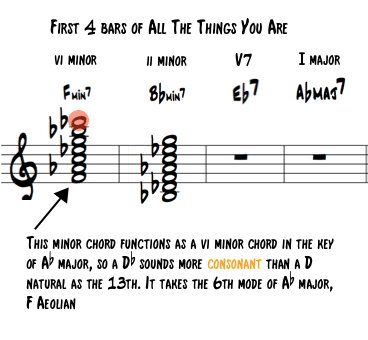

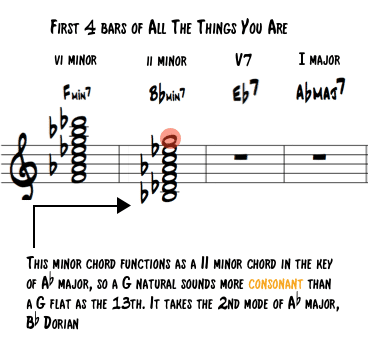

Take the first 4 measures of the famous tune All The Things You Are:

There are two minor chords in these 4 measures, but they are functioning differently within the key center. The first (F minor) is functioning as a Vi chord in the key of Ab major:

…and the second minor chord (Bb minor) is functioning as a ii chord in Ab major.

Because of the differences in function, their upper structure chord-tones cause varying degrees of consonance/dissonance in terms of the overall scale.

When F minor is functioning as a Vi chord, the 13th is flatted (Db) because it’s more consonant sounding than the natural version (D), when it’s functioning this way.

Note that this consonance/dissonance is gauged from the overall scale and not simply judged on how that chord-tone sounds held-out for an extended period of time against the chord. In this example, both the D and Db would sound dissonant if simply held, but the Db sounds more consonant within the overall scale on F minor in this harmonic situation. This can get confusing, as sometimes the more consonant chord-tone choice in terms of the overall scale is actually more dissonant when held for an extended period of time over the chord.

Now, there is no rule that says you have to choose the Aeolian mode in this example, the chord is still just F minor (F-Ab-C-Eb), but the mode gives you a way to quickly think of the most consonant upper structure chord-tones for the overall scale.

The mode for a chord tells you the most consonant sounding upper structure notes in terms of the overall scale, and reorganizes all of those notes into a convenient scale.

People think that the modes tell them the “right” notes for a chord, but this is not necessarily true. There are really no “right” notes, just consonant and dissonant notes. The more advanced you become, the more you’ll explore “dissonant” sounds and how to control them and use them in melodic ways.

Always ask yourself, “How is this chord functioning, what is the appropriate mode, and how does that influence the consonance/dissonance of the 9th, 11th, and 13th?”

Then, you’ll understand why that mode is the appropriate baseline choice (we’ll talk about “baseline” scales later) for what notes sound consonant in terms of a scale.

You want to get out of the habit of just blindly applying a scale to a chord. You need to understand the why if you want to advance.

Step #2: Overcome the “Parent-Scale-Shortcut”

One of the worst habits acquired by using the Chord-scale system is the need to “calculate” what scale to use over what chord.

If you have to spend even a fraction of a second thinking about what scale fits over what chord, you’re doomed.

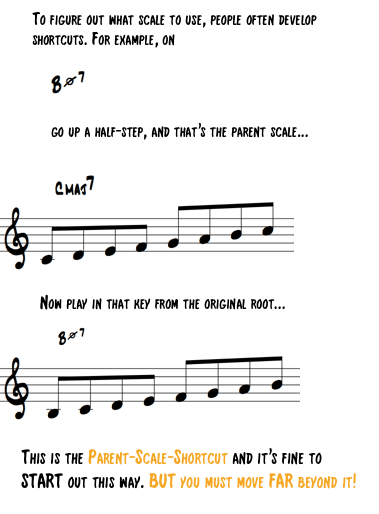

This thinking of a parent scale is a shortcut that must be surpassed. Yes, it’s perfectly okay to begin that way, but you must move beyond it. Let’s take a look at what the parent-scale-shortcut looks like and how we can move past it…

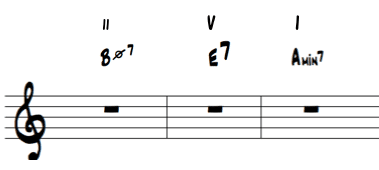

First, I would see/hear/think of a chord, perhaps the B half diminished chord in the following minor ii V I progression:

Then, here’s the shortcut thinking: I think “Okay, B half diminished is the 7th mode of C, the Locrian mode. So, the notes that work are B to B in the key of C major”

And by the time I’m done calculating what scale to use, the chord is long gone…

How do we get past this shortcut thinking and “just know” what scale works? The secret is mental rehearsal what we often call visualization. You mentally rehearse the scale over and over until there’s no thought necessary to conjure up the necessary information.

Let’s practice…

Taking B half diminished again, we know it’s the 7th mode of C major:

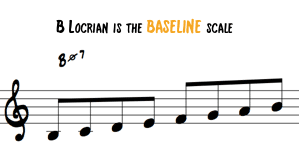

This scale is what I like to think of as a “Baseline” scale. We’ll get more into this later, but for now, think of it as the most basic and “un-altered” version of a scale that we can consistently use over a specific chord.

To practice forming the correct mental structures and surpassing the parent-scale-shortcut, you need to begin to think of the chord as its own entity rather than a piece of something else. In other words, you must form a mental and physical (on your instrument) relationship with each chord.

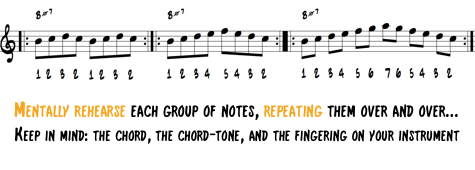

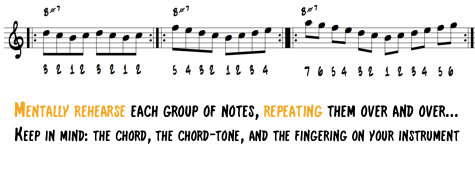

Try these simple mental exercises:

Mental Exercise #1:

Run through 12321, 123454321, and 1234567654321 in your mind. Say the numbers in your mind and visualize playing each note in your mind, while simultaneously thinking of the chord, B half diminished. Yes, it’s a lot to mentally juggle! Take your time…

Mental Exercise #2:

Now do the same with 32123, 543212345, 7654321234567

Just with these two simple metal exercises, you’ll start to conceptualize B half diminished as its own thing, and discard with any “pre-thought” of calculating the parent scale and mode.

Here are few more tips to overcome the parent-scale-shortcut:

- Always think in terms of numbers

- Make up your own exercises like the ones you just did. HINT: try making exercises that start on chord-tones other than the root, or ones we didn’t get into, like the 9th, 11th, 13th, or altered chord-tones

- You don’t need to think of any mode names, they’re just an extra thought you can discard

- Pay close attention to forming a mental relationship to each chord-tone within a chord

- Keep the chord’s name in your mind as you do all the exercises to strengthen the connection between each chord-tone and the chord

And If you want a TON of progressive visualization exercises and instruction that guides you through this mental process and takes you light years beyond what we’re discussing here, make sure to check out the Jazz Visualization Course.

Step #3: Understand the chord and chord-tones both mentally and aurally

Once you overcome the parent-scale-shortcut and begin to form a direct mental connection to each chord, you want to further your mental study on chords, while adding in an aural element to the picture as well.

The Chord-scale system leaves you high and dry on the uniqueness of each chord-tone, both mentally and aurally, and it’s up to you to fill in this gap.

To illustrate the problem, let’s take our B half diminished chord again…

Now, if we’re thinking in terms of a parent scale, or if we’ve just started to think of the chord as it’s own entity and have begun to practice the simple exercises we talked about, then we’re not quite going to have a solid grasp on each chord-tone, especially what they sound like.

So, if I say to myself, “What’s the 13th of B half diminished,” it may take me a moment to figure it out and I’ll still have no idea what it sounds like in the context of the chord.

This is a huge problem.

Each chord-tone as it relates to a chord:

- Should be easy to mentally access (i.e. what’s the 13th of B half diminished?)

- Should be easy to hear and sing (i.e. I’m listening to a melody and can easily identify “that’s the 3rd of a minor chord in the melody, now it’s the 13th of a major chord etc”)

To achieve these two chord-tone goals takes a combination of visualization and ear training practice.

Here’s an effective exercise to try:

- Sit at a piano (If available. Otherwise, just practice in your mind)

- Play the basic root position chord (1357), we’ll use B half diminished as our example (BDFA)

- Now, mentally say in your head “B is the root of B half diminished, D is the 3rd of B half diminished, F is the 5th of B half diminished, A is the 7th of B half diminished”

- Repeat step 3 over and over until you can do it in any order (i.e. F is the 5th of B half diminished, B is the root of B half diminished, A is the 7th of B half diminished, D is the 3rd of of B half diminished)

- Next, add in your upper structures (9 11 13) using the “baseline” scale, in this case, the Locrian mode (i.e. mentally say in your mind “C is the 9th of B half diminished, E is the 11th of B half diminished, G is the 13th of B half diminished”)

- Repeat step 5, but add in ALL chord-tones in any order

- Now, we’ll get to the aural part. Play the basic root position chord (1357) in the left-hand and play the root an octave above in the right-hand. We’ll use B half diminished as our example. (BDFA in the left hand, and B an octave up in the right hand)

- Pay attention to the specific chord-tone color you hear for the specific chord-tone. You have to listen closely and repetitively, but each chord-tone does have a distinct color as it relates to its chord.

- Repeat step 8 with all other chord-tones (3 5 7 9 11 and 13)

Through this seemingly simple exercise— it’s actually quite difficult and time consuming —you’ll gain both the mental and aural chord knowledge that’s easy to skip over with the Chord-scale system. And If you want premium ear training tapes that automate this process that you can take anywhere you go, we’ve created those for you here.

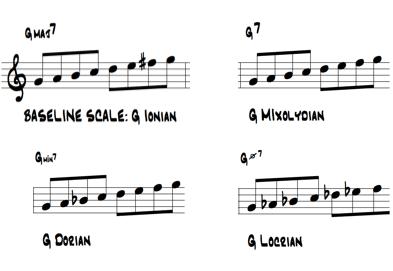

Step #4: Stop thinking in terms of dozens of scale choices and use baseline scales instead

Ok. We’ve mentioned this idea a few times. Let’s get into it…

A “baseline” scale is the most basic and “un-altered” version of a scale that we can consistently use over a specific chord. In other words, it’s the simplest form of a scale that could be used on a chord.

Here are the baseline scales for the 4 chord-qualities you frequently encounter. Major, dominant, minor, and half diminished.

Now, I can hear you saying, “Wait, there are way more chords than major, dominant, minor, and half diminished,” and while this is true, these baseline scales can give you a way to simplify your thinking into just these 4 chord types.

Here’s a simple example…

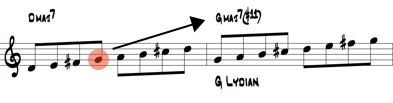

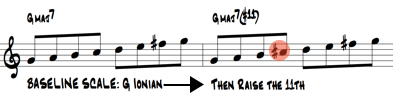

Suppose you see the chord “G Major 7 #11”

Using the Chord-scale system, we would find the mode that fits this chord— G Major #11 is the Lydian mode of D Major— but for most chords, this is overkill.

If you know the baseline scale, you can simply raise the 11th, and you’re good to go.

No need to think of a parent scale, scale choices, or even the name of a mode.

This way of thinking works extremely well for major, minor, and half diminished chords because there are very few alterations that typically occur. The common alterations are:

Major: #11 (same as #4, or b5), #5

Minor: Major 7, b6 (minor chord functioning as a Vi chord), b6 and b9 (minor chord functioning as a iii chord)

Half Diminished: #9 (Often called “Natural 9”)

See how easy that is?

So, for most chords thinking of baseline scales makes things super easy.

Now on dominant chords, it’s a bit tricker to use…

If you’ve learned your altered scales and moved beyond the parent-scale-shortcut with them, meaning that you don’t need to calculate anything to know what to play over any form of an altered dominant, then you are ready to begin to think of dominant chords in this way as well.

If you haven’t achieved these prerequisites yet, then keep working on your mental capacity with altered dominant chords before you try to use baseline scales for dominant chords.

Here’s an example of using baseline scales on dominant chords…

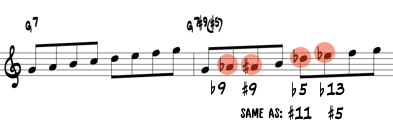

Let’s take the chord G7#9#5

Often, this chord symbol implies a b9 and b5 (same as #11) as well, so we need to be able to work those into our mental thinking. We also need to be able to automatically know that the #11 and b5 are the same, and the b13 and #5 are the same.

If you’ve moved past the parent-scale-shortcut with altered dominant chords like suggested above, then you should be able to do this.

Think of G7 and simply use:

- The b9 and #9 instead of the natural 9th

- The b5 (same as #11) and #5 (same as b13) instead of the natural 5th and natural 6th (13th)

On the surface, it looks the same as thinking of the altered scale, after-all, they are the same notes, but, you’re getting there in a more meaningful way and understanding how each chord-tone is being altered.

Remember, there’s nothing wrong with thinking about the altered scale or any other modes, but they are a stepping stone to this type of more direct thinking.

What are the advantages of thinking this way?

- You simplify all dominant chords to simply “dominant” with added tensions

- You learn to hear each “flavor” of a dominant chord— use of different altered notes in a voicing create a different flavor so to speak.

- You learn to access each specific altered tension as it relates to a specific chord, both mentally and physically

- You learn to use the natural and altered versions of a chord-tone within the same line. Yes, there’s no rule that says you can’t do this, and if you’re strictly using a scale to improvise, it’s conceptually much more difficult to do this.

- It gives you a supplemental way to think about dominant chords, rather than just scales. You don’t have to exclusively think one way or the other. You can combine the concepts.

- You don’t need to know a million scales. Once you know the baseline scales, you can just add small alterations to get the colors you want and focus on the melodic colors you wish to express

One thing to note is: You can only think in terms of baseline scales if you truly understand each chord-tone and have easy mental and physical access to each one.

Obviously, if you ran into G Major #11 and you can’t quickly think of the 11th, then you won’t be able to use this way of thinking.

And one other caveat – You need to understand the subtleties in the way people notate chords. As seen in the dominant example above, often, chords are written in a way that one alteration implies others. As we saw before, If they write G7#9#5, this could also imply a b9 and #11.

This is where things get quite complicated, and the only way to know exactly what chord is being played behind you is to develop your ear and learn to hear the subtleties of voicings– something we cover in the Ear Training Method.

You don’t have to think in terms of baseline scales, but you should try it and see if it adds a helpful way of thinking to your improvisational toolbox. At the very least, it should help you in certain situations.

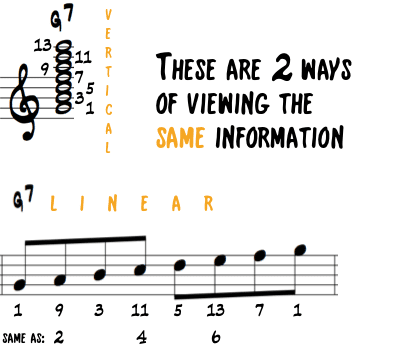

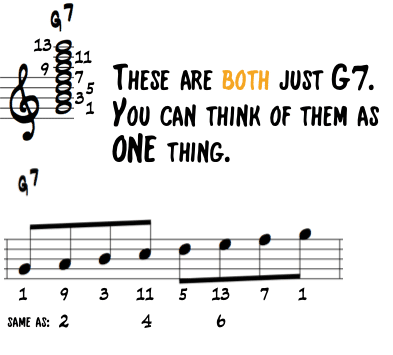

Step #5: Turn linear and vertical thinking into one thing

The more you use the Chord-scale system, the more you’ll get used to “applying” scales to each chord, which tends to create a mental-divide between the scale and the chord, when in reality, they’re just two ways of viewing the same information.

One is linear, and one is vertical:

Something I’ve realized studying with a lot of great players is that they’re constantly finding ways to simplify their way of thinking.

Always try to simplify your concept into things that are easier for you to think about. Why think about two pieces of information when one will do?

I like to think of the chord and the scale as one “thing,” meaning, G7 is just G7:

This is an easy thing to do once you overcome the parent-scale-shortcut, develop a strong mental and physical relationship with the chord-tones, and begin to think in terms of baseline scales.

Step #6: Understand that improvisation is NOT randomly mixing up notes in a scale

The absolute worst thing that the Chord-scale system does is promotes the idea that improvisation is mixing up notes of a scale.

Knowing your scales does NOT mean you can improvise and a little scale knowledge plus a few jazz rules is NOT the art of improvisation.

Jazz Improvisation is about creating strong melodies over chord progressions in a spontaneous way, while speaking the jazz language.

Of course there are many other aspects to it, like freedom of expression and interaction, telling a story, developing one’s ideas…but one thing is for sure: it’s not randomly mixing up notes of a scale, and the problem? The Chord-scale system:

- Tells you little about HOW to create a strong melody

- Tells you nothing about the sound of each chord-tone in a given harmonic setting

- Tells you nothing about how jazz actually sounds

- Tells you nothing about jazz phrasing, articulation, feel, swing etc

And the list goes on…That’s why ALL this scale stuff is just the beginning and it’s primarily mental.

To turn the Chord-scale system into music, you must immerse yourself in jazz: listening, transcribing, acquiring language, and learning from your heroes. Make sure you understand how to practice.

Learning how to improvise is a life-long pursuit and not falling into this “randomly mixing up notes in a scale” trap will save you years of frustration.

Unlocking the Chord-scale system

To unlock the Chord-scale system takes a re-framing of the information that you’ve become so used to taking for granted.

Here’s your plan of action:

- Realize the modes are just a starting point, like your times-tables

- Understand the purpose of modes and why they’ve become so popular

- Come to grips with how the Chord-scale system has failed you

- Understand the relationship between chord function, modes, consonance/dissonance, and upper structure chord-tones

- Overcome the “Parent-Scale-Shortcut”

- Understand chords and chord-tones both mentally and aurally

- Learn to use baseline scales

- Turn linear and vertical thinking into one thing

- Understand that improvisation is not mixing up notes in a scale and that it’s all about immersing yourself in the music

There’s a lot to work on here, but if you carefully follow the information and steps we’ve talked about today, you’ll be a BOSS of the Chord-Scale system.

And if you want to move beyond the Chord-scale system and fill in all the gaps in your music theory knowledge, make sure to check out our fundamental course Jazz Theory Unlocked.

In this course we’ll give you an easy to understand framework that will help you ingrain the essential elements of jazz theory and harmony, allowing you to discover how jazz tunes really work.

Inside you’ll find:

- 60 animated video lectures

- 15 step-by-step lessons

- The Framework of the 9 Elements

- A breakdown of Diminished Chords

- and much more!

If you’ve been confused with chord progressions, struggling to connect chords in your solos, or frustrated with playing tunes, this course is for you.

Get your copy of Jazz Theory Unlocked today and unlock your harmonic potential!