Have you ever thought about why you’re practicing every single day for hours and what you’re actually trying to achieve with all your hard work? To play better over a G7 chord? To master that tricky ii V I? To get a better sound? To improve your technique? To play fast and loud? Of course all of these things matter, but none of them are the true goal of practicing.

The whole reason you’re practicing is to perform a tune.

Sounds simple, doesn’t it? But then why does practicing jazz improvisation have to be so complex?

Everything you do, whether it be ear training, transcribing, learning language, or anything else…everything leads to performing tunes.

This subtle yet powerful point gets lost somewhere along the way and we end up spending our precious practice time in the endless rabbit-holes of jazz improvisation, the infinite minute details, rather than where it counts.

You know how it goes…

You jump from one thing to the next, practicing all the things you think you should practice. You spend time on scales, arpeggios, tone exercises, technique exercises, transcribing, soloing over lots of tunes using play-alongs…but for some reason, you’re still not improving the way you want.

And really it’s pretty simple…

In our frantic race to become a great jazz improvisor, performing tunes has become an afterthought, instead of the focus.

By realizing the true endpoint of all of your practice, to perform well over tunes, you can restructure your practice routine to achieve your goals more quickly and make better use of your time.

Practicing jazz improvisation just got a whole lot simpler.

Rethinking & Restructuring your jazz improvisation practice routine

There’s so much to practice…

A million different things and each one takes so much time to gain any sort of mastery over. But, this infinite sea of stuff to practice is actually an illusion.

You see, most of the time, we think of “tunes” as a separate category of practice from “ear training,” which is different than “jazz language,” and not the same as “transcribing.”

We also consider “visualization” its own thing, “technique,” “sound,” and any other practice topic we can possibly think of as a separate compartment, each needing its own attention.

The problem with this?

That’s a whole lot to practice!

You’ll drive yourself mad.

Who has the time? Even if you did have the time, why would you want to make things so difficult and convoluted?

Feeling overwhelmed and not knowing what to practice is a huge problem. It leads to skimming the surface on everything, and not actually improving at the true goal: to play well over tunes.

So instead of thinking about each practice topic as a separate thing, what if we started from the endpoint and worked backward from there? Might that be a better way?

The whole idea is to start with the goal of performing ONE specific tune and structure your daily practice routine to reach it.

You can start to shift your practice routine in this direction starting today. It’s not difficult and it just might be the subtle change you’ve been looking for.

Your Tune Based Practice Plan

Rethinking your practice routine in this way is simple. Make no mistake though…by no means does it allow you skip the tremendous amount of work needed to improve at jazz improvisation.

But, it does conceptually simplify how you approach your practice, making you focus more easily and consistently, while directly moving you toward the goal of improving at tunes with the aim of performing them.

The idea of a “Tune Based Practice Plan” is easy: Instead of the tune being an afterthought that you have to apply everything to, you instead begin with the tune and ask yourself, “What’s required to perform this tune?”

Here are the 3 steps to your tune-based practice plan…

Step 1.) Choose a tune

This is not rocket science. Choose one and ONLY one! Less is more. By really focusing one one tune, you will learn a lot more than trying to tackle ten at once.

Perhaps start with one of these 5 tunes you should know, or check out how to build your Jazz Repertoire.

Step 2.) Ingrain the right melody and chord changes

Once you’ve got a tune in mind, it’s time to focus on the melody and changes.

It sounds simple, but in today’s world of lead sheets and fake-books, it’s become pretty difficult to learn the “right” chord changes.

Learning the changes to a tune does NOT mean memorizing chord changes from a lead sheet, arpeggiating chords, and determining chord-scale relationships.

The only reliable way to accurately learn the melody and chord changes to a tune is to check out what’s happening on multiple recordings.

Even if you could get your hands on the “perfect” lead sheet for a tune, it still wouldn’t give you a crystal clear picture of what’s going on harmonically because in jazz, many of the specific chord sounds and alterations vary depending on the specific recording, the musician comping, or even the particular chorus.

That’s right. You might listen to a recording of Stan Getz playing Stella by Starlight…

And then, you might hear Miles play it with Herbie Hancock…

The specific chord voicings are not precisely the same, yet the “big places” the tune heads to are. Finding these macro details, while understanding the micro details is key to successfully playing over any tune.

When you learn a tune, it’s your job to understand what chords make up the fundamental structure of the tune, and where there may be some variance.

So, in some sense, because of all this variance, there’s no 100% “right” changes, however, there are definitely chord changes that are just plain wrong. And much of the time, learning from a lead sheet or a fake-book causes you to learn the wrong changes.

By listening and studying different recordings of the tune, you’ll quickly learn the “right” changes and ingrain both the melody and changes on a much deeper level than if you learned them with your eyes from a lead sheet, instead of from a recording with your ears…

Here are a couple articles that will guide you through the process of learning the changes to standards straight from a recording:

- A Downloadable Handbook on Learning Tunes From a Recording

- How to Learn Jazz Standards with the Piano

Step 3.) Aquire and develop soloing strategies for each part of the tune

Most people stop right before this step once they’ve learned the melody and chord changes leaving the rest up to chance, but jazz improvisation is not about chance. It’s about being prepared.

Once you’ve got the right chord structures accurately ingrained in your mind, fingers, and ear, you need to learn how to play over it, after-all, this is the actual goal you’re trying to achieve with ALL of your practice.

Take a second to digest that.

ALL of your practice is meant to culminate in you performing this very tune you’re working on, so this is where the bulk of your practice time should be spent.

Here’s the idea…

For each piece of the chord changes, you want to acquire various strategies or approaches to how you’re going to solo over it.

Not one strategy for the whole thing and not one strategy for each piece, but several strategies for each piece.

Now, with each tune you work on using this method, the better you will get and the more knowledge you will have at your disposal…

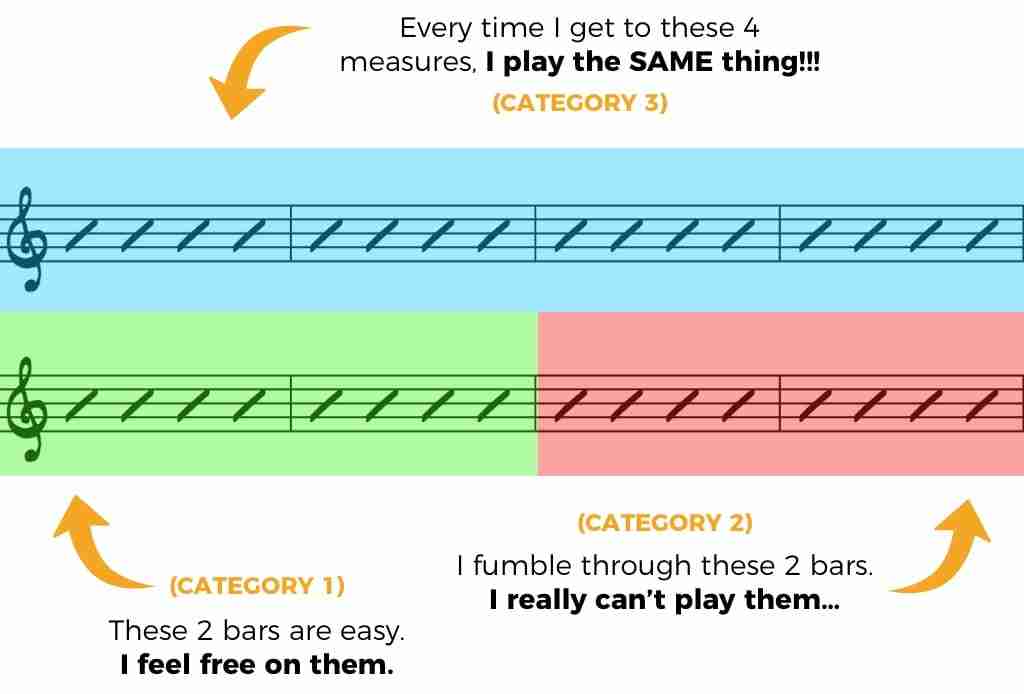

But, no matter what, every part of the chord changes of a tune will fit into one of these 3 categories, and keep in mind that a part of a tune could be just about anything…a whole A section, 8 bars, 4 bars, 2 bars, a few tricky bars, a single bar, a transition between bars, or even just one specific chord for two beats:

- Category 1: Groups of chords you are already comfortable with – not only are you comfortable with these sections of the tune, but you also vary your playing in these parts and have melodic freedom

- Category 2: Groups of chords you are not comfortable with – these parts of the tune are difficult. You may be able to “get through” these chords or sections, but you are fumbling and barely making the changes

- Category 3: Groups of chords you are comfortable with, but play the same thing on every time – this happens all the time, in fact, if you play a tune long enough, all the Category 1 groups eventually become these Category 3 groups because you naturally become bored of the things you play all the time.

Always, with every tune you know, every tune you kind of know, and every tune you don’t know, you can pull apart the chord changes into these 3 categories.

Let’s take a look at an example.

In this example, the first 4 bars you can play just fine, but you tend to repeat yourself over and over. The next 2 bars are easy for you, and the last 2 bars you haven’t gotta clue how to approach.

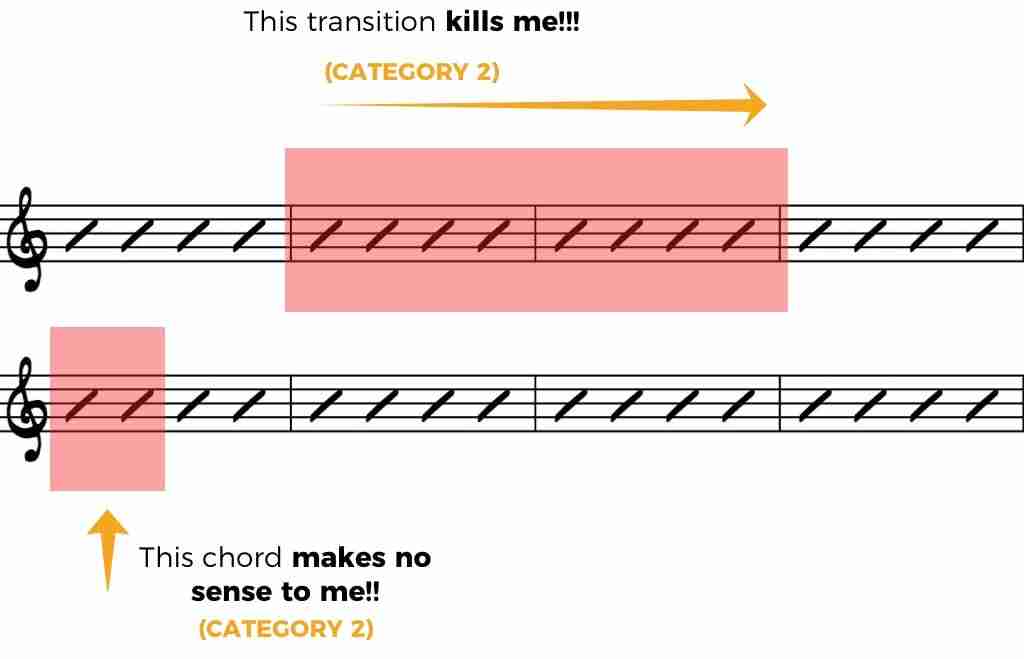

Or maybe, it’s a transition between one measure and the next that gives you trouble. Or, perhaps it’s just a single chord that lasts 2 beats…

All of this is valuable information.

You’ve defined what you can do and what you can’t. This is the roadmap telling you exactly what you need to work on to be able to perform this tune well.

And it’s okay if an entire tune is all Category 2s for you right now. You have to start somewhere! In fact, a tune based practice plan is a great way to start out because instead of feeling the need to tackle everything in jazz improvisation all at once, you’ll instead work on only the essential elements that appear in the tune right in front of you.

So what do you do with each of these groups of chords in the various categories?

Category 1s you can let be because you can already play over them.

But Category 2s and 3s need some work…

And here’s a simple approach for you.

For every place that either gives you trouble or you play the same thing every time, come up with three ways to play over it that YOU like.

Maybe over a tune like All The Things You Are, your Category 2s and 3s look like this:

- The first measure moving to the second measure

- The entire bridge or the second half of the bridge

- The 8 bars after the bridge

So with all of these spots, your job is to transcribe, create, or combine anything you know to define three clear ways to play over each of them.

The point is, assuming you followed step #1 and got the right chord changes and that you have a clear understanding of the chord structures going on and can access them with no effort, then the reason these spots of the tune give you trouble right now is that you lack an idea of how to approach them.

And if you know what’s going on harmonically and you have the chord fundamentals together, then all you need is some concrete ideas of how to play over each of these places in the tune.

A single afternoon transcribing your favorite player soloing over these sections, or an evening spent writing out your own exercises over these measures of the tune will give you the practice tools necessary to improve at soloing over these specific parts of the tune.

Think about it. In one SINGLE practice session you could find solutions to all of these problems.

Then, all you have to do is spend some dedicated time practicing the lines, exercises, and harmonic information that now lie before you.

Here are a few step-by-step articles that will help you figure out this process:

- Breaking Down a Tune: It Could Happen to You

- Creating Your Own Exercises From a Transcribed Line

- How to Steal Musical Lines and Ideas

- Getting Jazz Language

Your practice goal is to transition ALL pieces of a tune from Category 2s and 3s, to Category 1s.

If Category 2s or 3s remain, you’re going to have difficulty with the tune.

Ok, so now you know what a “tune based practice plan” is and how to do it, but you may still be wondering why it helps you so much to structure your practice around tunes.

Well, if you give it a chance, rethinking your practice routine in this way will actually help you a lot more than you ever I thought.

It’s so easy to think, “This week I’m working on Autumn Leaves” and zero in on all the necessary requirements needed to perform that tune, whether it be transcribing sections of solos to figure out how you’re going to play over them more effectively, learning the chords of the tune from a Bill Evans recording, or coming up with your own line over the bridge. Literally all of your practice can be structured around this one tune.

Now, contrast that to, “This week I’m going to transcribe a Dexter Gordon solo, work on 5 different lines, try to incorporate this new scale I heard about, do some ear training on altered dominant chords, work on my swing feel, practice out of this new etude book I just got…and oh yeah…learn Autumn Leaves”

Which practice plan do you think is going to be more effective toward performing tunes, the true goal we’re trying to achieve with our practice?

Which one will you actually retain the information from more easily? Which one will you progress faster with? Which one will allow you to perform Autumn Leaves with more musical clarity, freedom, and confidence?

This doesn’t mean that you always have to focus all your practice around a single tune all the time. Of course you should do some ear training on the go or work on some crazy concept that interests you.

You can of course structure your practice any way you see fit. Perhaps you want to start off with some tonal or technical exercises – you could actually structure these around the tune too, and that would be even more beneficial, just sayin’ – but the idea is to use this strategy as a guideline to simplify how you approach practicing.

It’s subtle, but it can make a huge difference…

10 ways a tune based practice plan will make you improve way faster

As you should know by now, a tune based practice plan can greatly simplify how you think about your day to day practice as a jazz musician.

This practice strategy does a few very helpful things:

- It defines the requirements for your practice – Every tune has specific requirements to play well over it. By choosing one tune as your starting point for your practice routine, you’re spoon-fed the things you need to practice. You suddenly know who and what to transcribe. You know what kind of language you don’t have at your disposal and where to find it. No more wondering what you need to practice!

- It focuses your practice time – Because you know what to practice, you spend your time wisely. You don’t think about everything you could possibly practice but instead you focus on what you need to practice to perform the specific tune. Your time isn’t wasted switching between topics. You dial in to exactly what will make you perform the tune better. You focus on what’s in front of you.

- It becomes easy to be consistent – One of the biggest problems in improving at anything is being consistent with what you’re trying to learn day in and day out. By simplifying your practice plan in this way, you’re making it easy for you to consistently practice. You’re in a crunch for time? You adjust. Can’t make it to the practice room? You visualize everything about the tune you’re working on. Because it’s easy to think about what you’re practicing, you’ll become more motivated toward being more consistent with your practice regardless of your time constraints. Excuses go right out the window.

- It forces you to become GREAT at the fundamentals – No matter how much we talk about ii Vs, or dominant chords, or practicing language in all keys, you probably still haven’t had the chance to dedicate the necessary time to these things to master them. But with this approach, that’s okay! For example, if You’re working on Autumn Leaves, you’re forced to work on ii Vs to successfully play the first 4 bars, or if you’re having trouble with the next 4 bars, you’re forced to finally give minor ii Vs the attention they deserve. With this approach, there’s no longer a need to spread your time out between all the fundamentals. Pick a tune, and let them come to you in an achievable fashion.

- It gives you a ton of ear training – You have all the ear training you want right in front of you by simply studying the recordings of the tune. By figuring out the melody and chords by ear, you’ll naturally push your ear to new heights, learn to hear intervals, bass lines, chord qualities, and lines. And, on top of all of this, because you’ll be learning all this with your instrument, you naturally connect your ear and fingers. This is the best kind of ear training you could ask for.

- It brings to light what you SUCK at – The easiest way to know what you’re not good at as an improvisor is to take a solo over a tune. After a chorus or two, I bet you can pinpoint the exact spots that you were just barely getting through or felt like you were faking it. The whole point of practice is to improve upon the areas that you’re weak in. If you don’t know where you’re weak, you can’t do this. But, with tune-based practice, it becomes apparent very quickly what you can and can’t do.

- It directly relates to the true goal of practice: performing a tune – While working on a specific chord, line, or concept is great, out of the context of a tune, it’s not directly related to the goal of performing tunes. Of course you can integrate everything you’re learning into tunes, but it’s even easier to structure your practice around a tune in the first place. In this way, everything you’re working on is automatically integrated for you as you practice because you’re already thinking in terms of the context of a tune.

- It gets you working on chord progressions and sequences of chords besides the most common ones – So much of the time, we think that if we just master a few essential chord scenarios that we’ll be able to tackle EVERY harmonic situation we’re every thrown into, and while ii Vs and things like them do make up a ton of the progressions you encounter, there are still many times where a tune makes use of these familiar elements in an unfamiliar or slightly awkward way. Focusing on these variations directly will make sure that you can deal with them when you’re performing.

- It keeps you improving continually on a tune – Much of the time we see a tune as something that needs to be checked off a list. “Okay. I learned Stella By Starlight. What’s next?” But that’s not really how it works. The more you play and perform a tune, the more comfortable you become with what you play over a tune. And sometimes, you become really bored with everything that you can come up with. That’s where this practice strategy comes in. It’s time to revisit the tune and develop a fresh perspective on all the spots that you’re bored with.

- It forces you to connect everything you’re practicing – While there’s nothing wrong with first transcribing a solo, then working on some random tune, and after that running through some jazz language, your practice can be much simpler and more effective if they are all connected. Placing all your practice topics around a specific tune gives you this huge advantage.

By restructuring your daily practice around the tunes you want to perform, you’ll aim yourself toward your goals in a much more direct way.

With some focus and constantly staying aware of the places that need the work, you’ll soon have a tune you’re so comfortable with, you’ll actually want to perform it in front of people.

And then shortly there after, you’ll have two tunes. Then three. And before you know it, you’ll have a complete set of tunes that you can’t wait to PERFORM, and that’s the whole goal of practicing!