The Brazilian composer Antonio Carlos Jobim is well known to improvisers with dozens of tunes frequently played and recorded in the jazz repertoire. However, one song in particular stands out…

The “Garota de Ipanema” or The Girl from Ipanema.

Composed in 1963, it propelled a Bossa Nova wave around the world and was recorded by some of the most popular artists of the time. But it also quickly became a victim of its own popularity, turning into a parody of itself in pop culture.

Despite all of this however, it’s a classic that is still played by some of the best musicians. And unbeknownst to many, contains some essential harmonic and melodic details that every serious player should know.

In this lesson we’ll take an in-depth look at the musical details of this classic standard and highlight 10 improvisation tactics taken directly from the solos of the masters to use in your next solo.

Let’s get started…

Learning the tune

The most famous version of this well known Jobim composition comes from the 1963 album Getz/Gilberto featuring João and Astrud Gilberto along with Stan Getz…

This version was recorded in the key of Db:

However it is also commonly played in the key of F, and in the examples below we’ll feature excerpts in both keys, so be sure to learn it both ways.

As with any tune the learning process should include 3 steps: Listen to it – Sing it – Play on your instrument.

Listen to the recording until you can sing the melody and hear the harmonic movement, then try to play it by ear on your instrument. As you do this, keep the lyrics in mind and ingrain the bossa feel as well.

3 Notable recordings

Along with the iconic Getz/Gilberto version, here are 3 other takes on The Girl from Ipanema that will give you some insight into the melody, harmony, and interpretation of the tune…

1. Frank Sinatra & Antonio Carlos Jobim

Recorded live for a 1967 television special “A Man and His Music + Ella + Jobim,” accompanied by the Nelson Riddle Orchestra with an arrangement by Claus Ogerman:

2. Elaine Elias featuring Michael Brecker

From her 1998 album Sings Jobim, with an arrangement that shifts keys throughout:

3. The Oscar Peterson Trio

Recorded for the 1964 album We Get Requests:

With each artistic interpretation ask yourself:

- How is the chord progression and melody approached?

- Any chords changed or subbed? Notable arrangements?

- How does each soloist approach the chord progression?

- What do you like about certain recordings and not like about others?

All of these answers will eventually shape your own approach to the tune.

Understanding The Chords

Learning this tune isn’t just about memorizing the melody and chords however, it also goes back to a strong understanding of jazz harmony…

To improvise effectively you need to hear the tune in terms of harmonic relationships in a key rather than a sequence of chord symbols. This will open the door to improving your solos and allow you to play it effortlessly in other keys.

And it all starts with studying the harmonic function of each sound. Let’s take a closer look at the two sections of the tune…

The A section

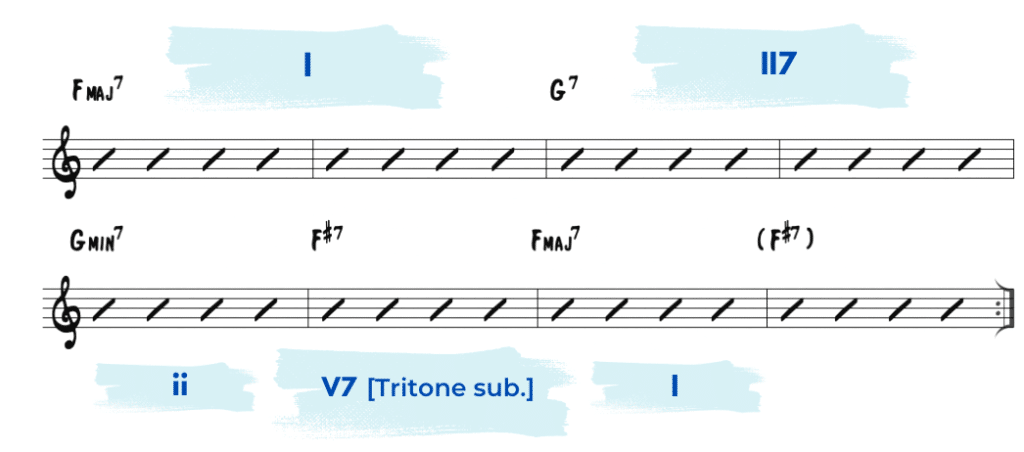

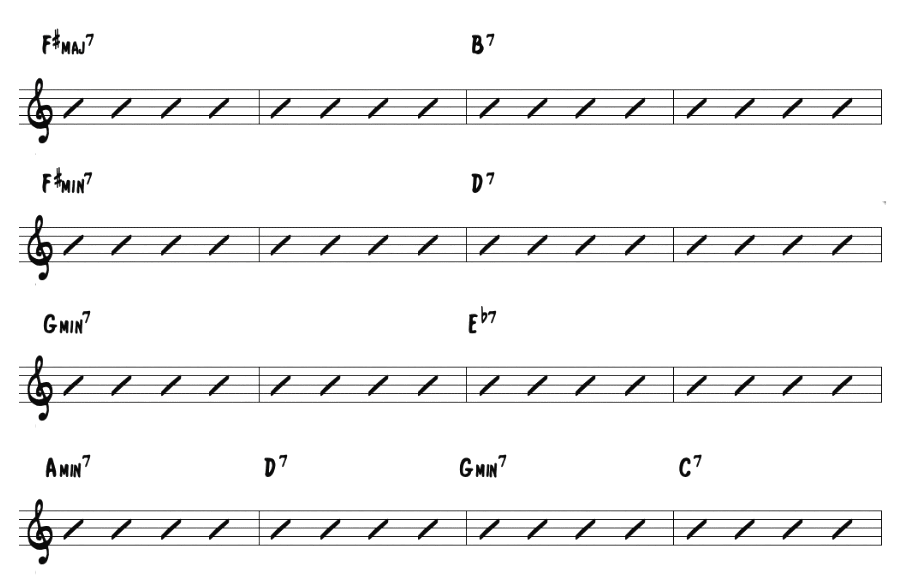

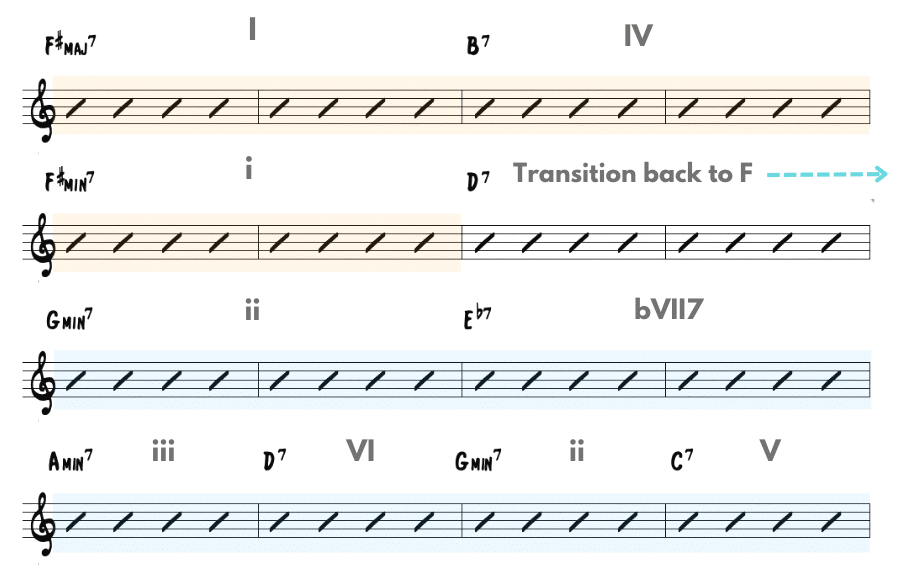

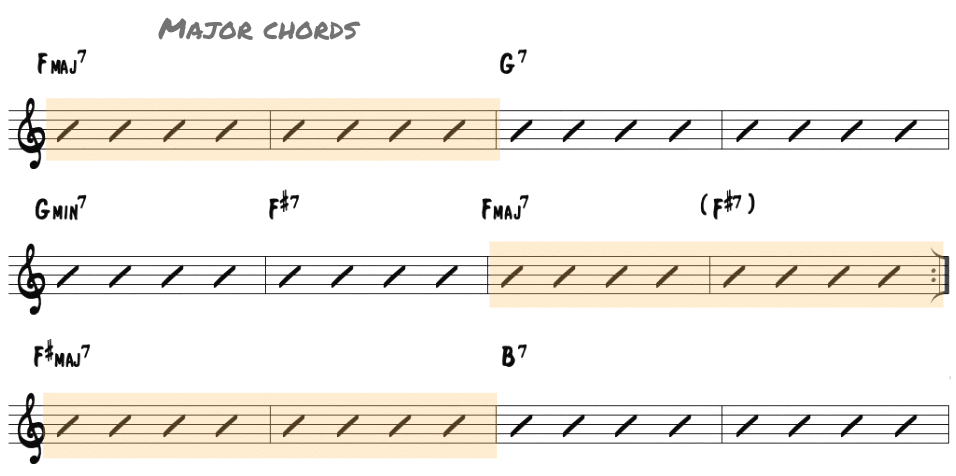

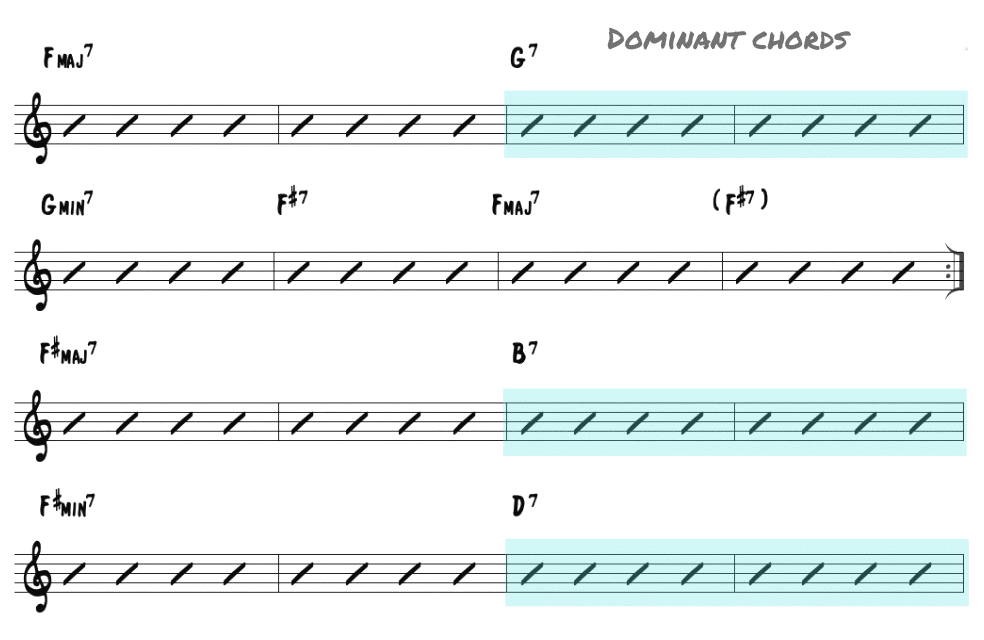

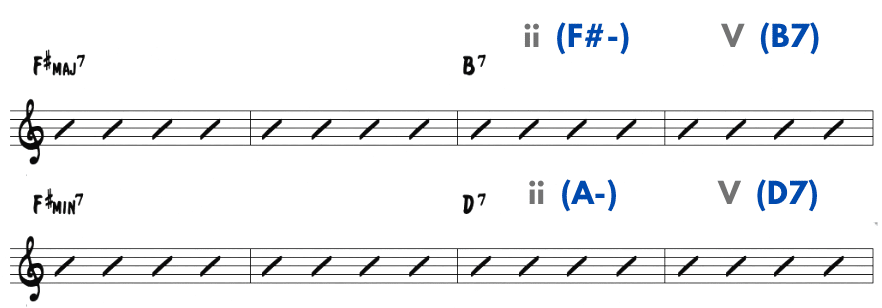

The first 8 bars of The Girl from Ipanema feature a simple and fundamental chord progression that’s an essential part of many standards: I – II7- ii – V7 – I (shown here in F major):

This is a progression that you should know and be able to play in all keys, noteably found in tunes like Take the A Train and Cherokee.

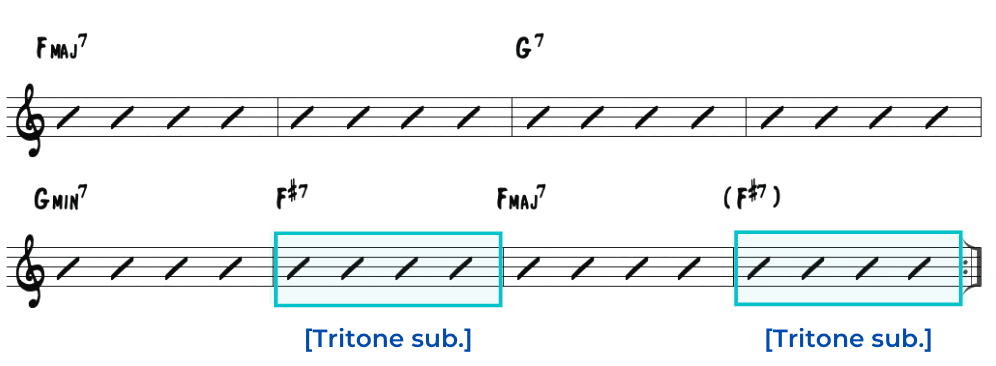

The I chord moves to the II7 – the V7 of V7 – and then a ii-V-I progression leads back to I. In this progression the V7 chord is often replace by a tritone substitution (F#7 in place of C7).

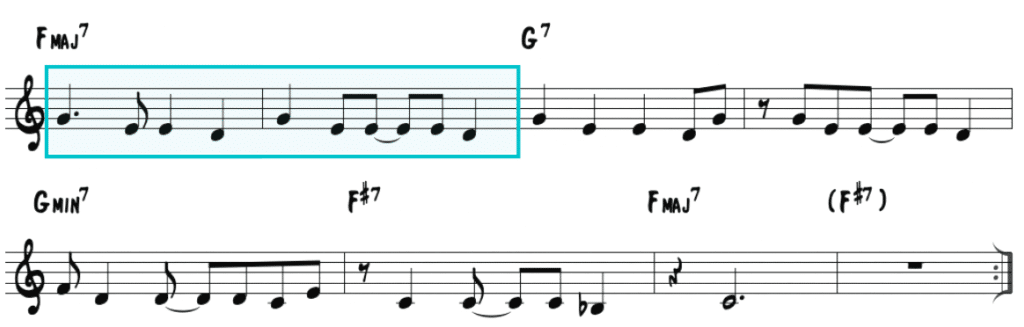

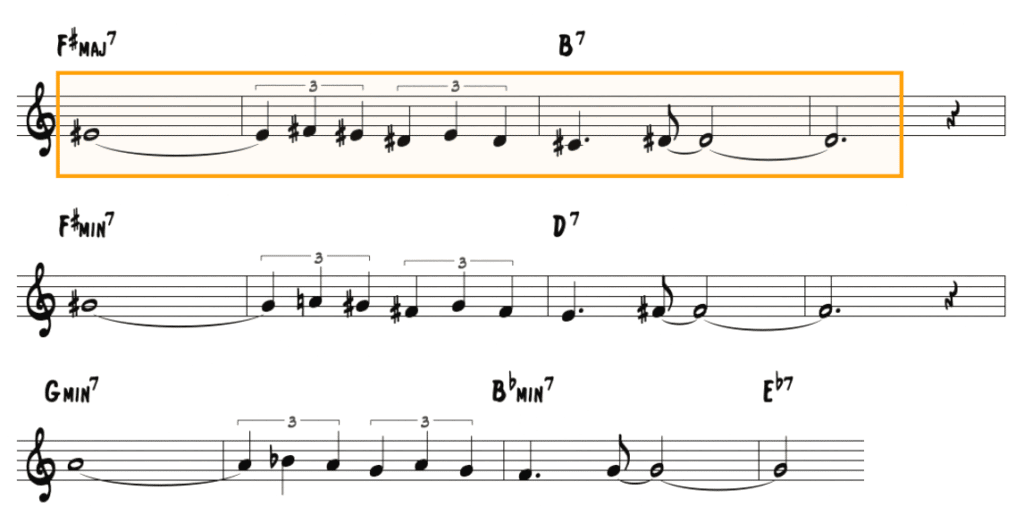

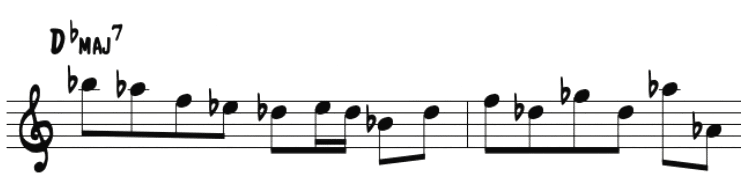

Let’s take a look at the melody of the A section:

In this section Jobim composes using melodic sequence to create his phrases. The melodic idea played over the initial F Major chord, highlighting the 9th and 13th of tonic sound, is repeated in the next two bars over the II7 (G7) chord.

Then the same shape is repeated in single measures over the ii-V-I progression. Showing a quality of strong and memorable melodies – simple, rhythmically strong ideas stated with intent and repeated.

The Bridge

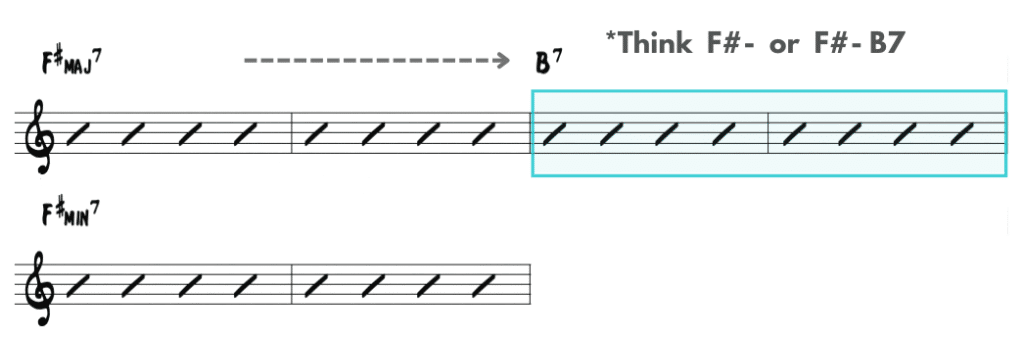

The harmony on the bridge begins a half-step up from the tonic, starting in F# major. And this is another harmonic tactic that you’ll see in some well known jazz tunes like Body & Soul or Cherokee.

The trick is to start in F# major and somehow get back to the tonic key of F by the end of the 16 bars…

And Jobim does this in a clever way, take a listen to the harmonic movement:

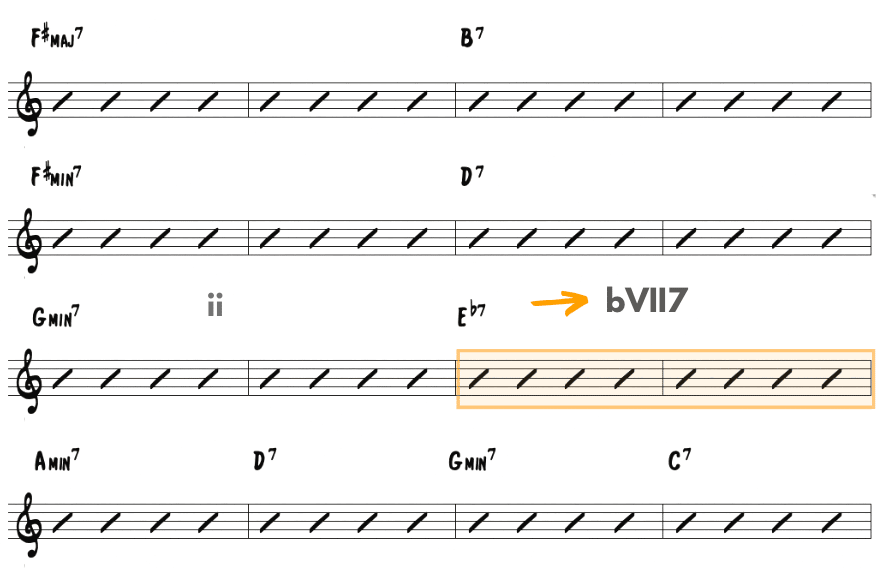

Here the F# Major chord moves to its IV chord and then to the parallel minor – this major to minor movement on the bridge also happens in Body & Soul and Cherokee as well.

From here Jobim then moves a minor 6th away to a D7 chord, and here we are effectively on our way back to the universe of F Major, (the VI chord leading to the ii).

The ii chord then moves to the bVII7 or backdoor ii-V leading to the turnaround which resolves back to the A section.

* Looking to master the essential progressions in the jazz repertoire once and for all? It’s time to get Jazz Theory Unlocked!

Now let’s focus on the melody of the Bridge. Here, Jobim once again uses melodic sequence – repeating the same melodic shape every 4 bars:

He starts on F, the previous tonic, now presented in a new harmonic context – as the major 7th of F#. He then repeats this 4 bar phrase twice more, ascending to the 9th of the F#- chord and later the 9th of the G- chord.

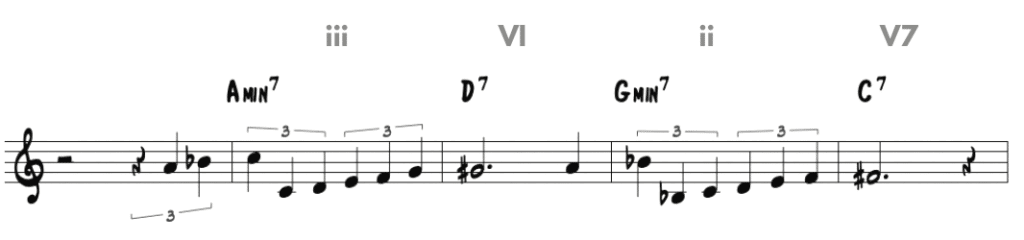

The last 4 bars of bridge feature a iii-VI-ii-V progression or turnaround leading back to F major, emphasizing #11 on V7 chords:

Now the question is, how are you going to improvise over this tune??

10 Tips for better solos

Here are 10 improvisation tips when soloing on The Girl From Ipanema, with examples from the recording we highlighted above…

1. Develop Major Language

One of the tricky parts of creating a solo over this tune isn’t unfamiliar keys or complex progressions, it comes down the basic chords you find in nearly every jazz standard!

Specifically, the Major 7th chord. If you look at the larger form you’ll find two bar sections of Major 7th chords popping up repeatedly:

And to create a musical solo in these spots you can’t just rely on scales and arpeggios, you need to have strong musical ideas that you’re hearing – what we refer to as language.

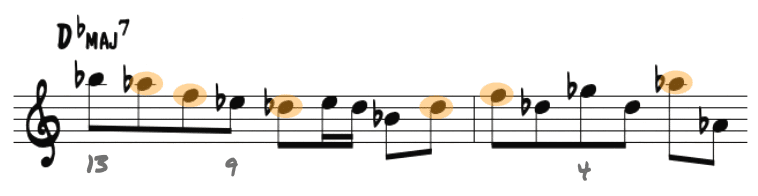

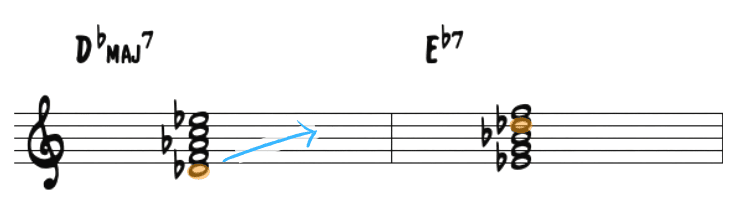

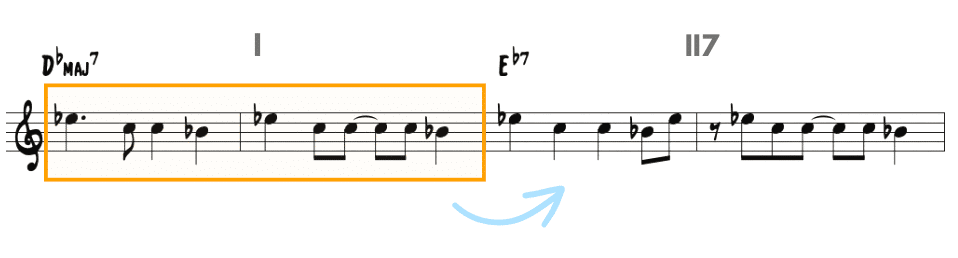

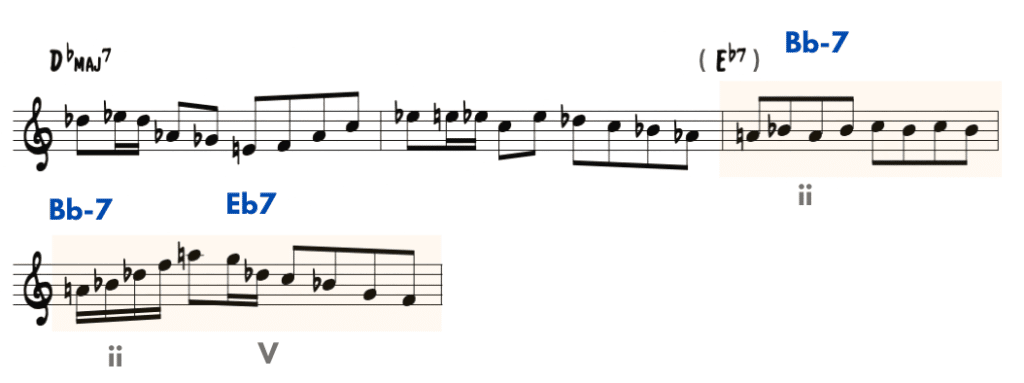

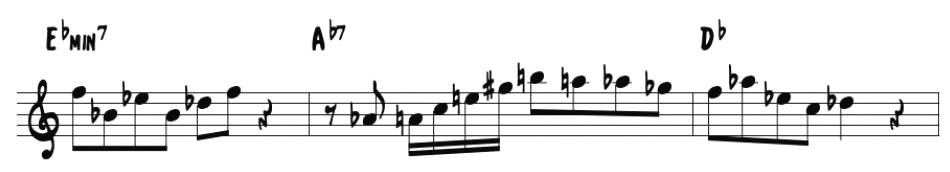

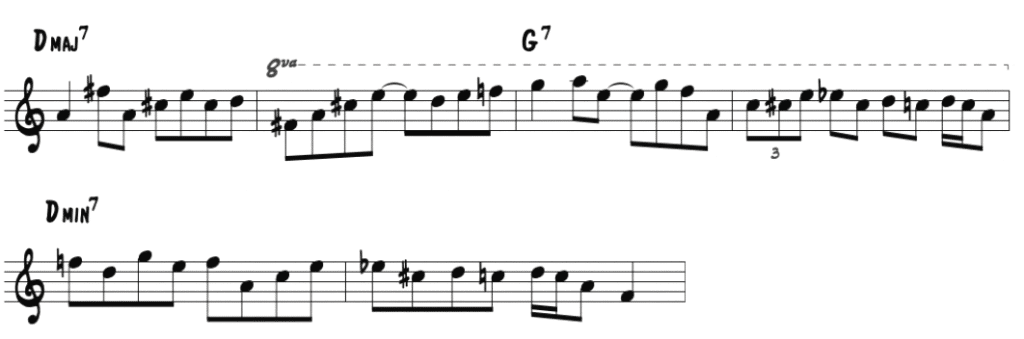

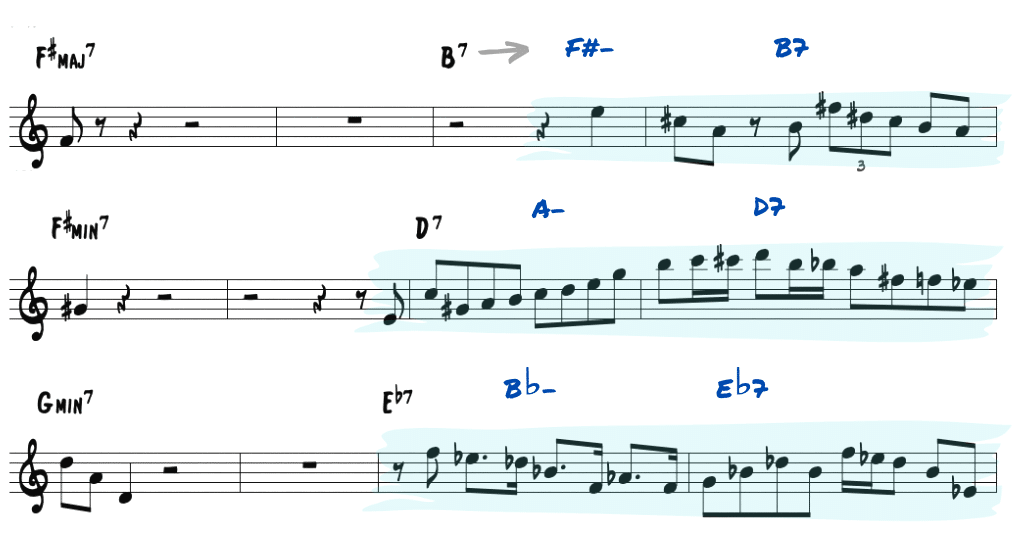

To see what I mean, listen to how Oscar Peterson plays over this Db Major 7 chord in his solo:

In this line you hear a defined musical idea using simple material, a major triad skeleton with the 13th, 9th, and 4th.

Here’s another example of major language from Oscar Peterson:

Remember, your solo statements don’t have to be complex or full of chromaticism to be effective, just stated with rhythmic definition and musical intent. With this in mind, let’s take a listen to a few examples of how Michael Brecker approaches these chords in his solo:

Again the melodic content here is simple, but played with rhythmic clarity – a major 7th arpeggio that includes the 6th and 9th. Here’s another example from Michael Brecker on major chord that is centered around the major triad w/9th and 13th:

Note how he utilizes the 4th intervals at the end of the line.

The crux of improvising on this tune comes down to creating musical ideas that aren’t scales or theory…rather musical statements played with intent, rhythmic clarity, and feeling. You want to be thinking and improvising in terms of musical ideas!

2. Develop V7 Language

Along with major chords, this progression also contains a number of static Dominant chords.

It’s important to note here that the dominant chords in this tune function differently – not as chords resolving to I, rather as sounds in their own right. And this means you need to have some tools to play musical statements on these sounds…

As with any sound, it’s incredibly useful to study how great improvisers approach the chord melodically. Here are two examples of Michael Brecker creating musical statements on the V7 chords:

In this line he implying D- to G7, bebop scale (link) fragment (major 7 moving to b7)

The ability to play over an extended or static dominant chord, not just as a chord resolving to I, is essential for any improviser. Whether it’s the Blues, Rhythm Changes, or any other standard, you need to have techniques for creating musical ideas on V7 chords.

The next line happens over an E7 chord. Notice how he implies ii-V motion, B- to E7 to create linear motion…

*Want an easy, step-by-step approach to developing the jazz language in your own solos?? Check out our Melodic Power Course and change your playing…

3. The I to II7 relationship

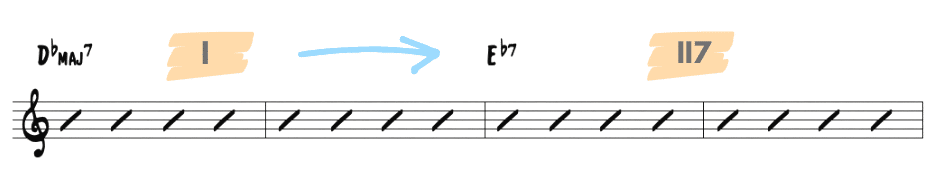

One of the defining features of the progression to The Girl From Ipanema is the Major I chord moving to the II7 in the first 4 bars of the tune:

This I to II7 harmonic relationship is found in a number of standards in the jazz repertoire like Take the A Train and Cherokee, and is one that you need to have melodic tools for.

The II7 chord (or V7 of V7) and shares a number of chord tones with the I chord:

The II7 is almost like the upper structure notes of the I chord (containing the 9, #11, 13) while retaining the root and third of the tonic sound. And Jobim utilizes these shared tones in the melody…

The initial statement on the I chord uses the 9th and 7th which then turns into the root and 13th on the II7 chord. And this is a tactic that you can use to your advantage as you navigate these chords in your solo.

Listen to how Oscar Peterson utilizes the shared tones between the I and II7 in his 2nd solo chorus:

In this line he retains the F and C on both sounds – the 3rd and 7th on the Db chord and the 9th 13th on the Eb7 sound. Like any other dominant chord, you can also imply the related ii-V here as Oscar Peterson does in this next line:

The approach you choose – repeating shared chord tones or opting for more linear motion – depends on what you are hearing and where you want to take your solo.

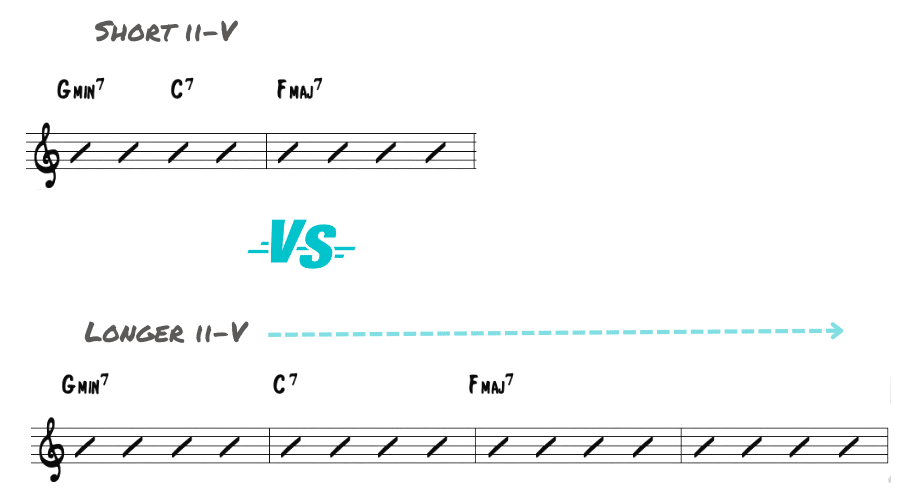

4. Playing Longer ii-V’s

Another spot in the A section that requires some specific musical tools is the ii-V-I in the last 4 bars…

In this tune each chord in the progression is sustained for one measure, and this can be surprisingly challenging to navigate due to the laid back tempo and slow harmonic rhythm of this tune.

If you’re accustomed to shorter one measure ii-V’s that you can apply licks, this progression will force you to play musical ideas.

Start by ensuring that you have some ii-V language and techniques. This also means having language for each chord type in this progression – Major, minor, and V7.

Let’s look at a few examples of how the masters approach this spot in the progression, starting with Oscar Peterson:

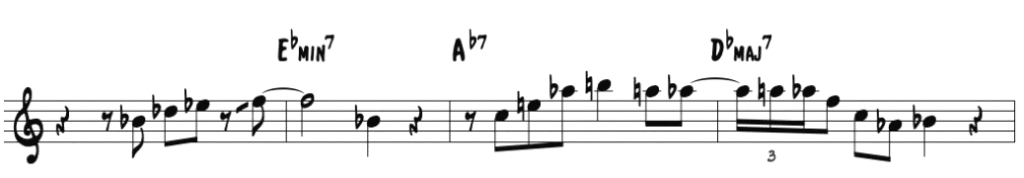

A musical phrase utilizing tension and alterations on the V7 chord (#5, #9, b9) and resolving to the I. Now let’s listen to what Michael Brecker plays over this longer ii-V:

In this line he arpeggiates the ii chord and alters the V7 chord before resolving to I. The key is having language and multiple techniques in your bag for approaching this sequence, from individual chord techniques to longer phrases

5. Using a Tritone Sub in a ii-V-I

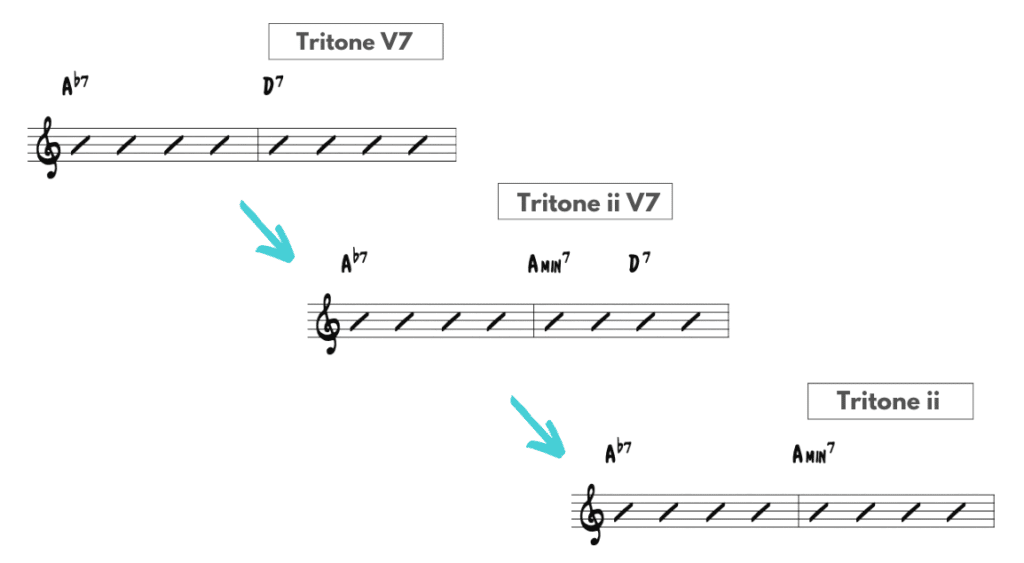

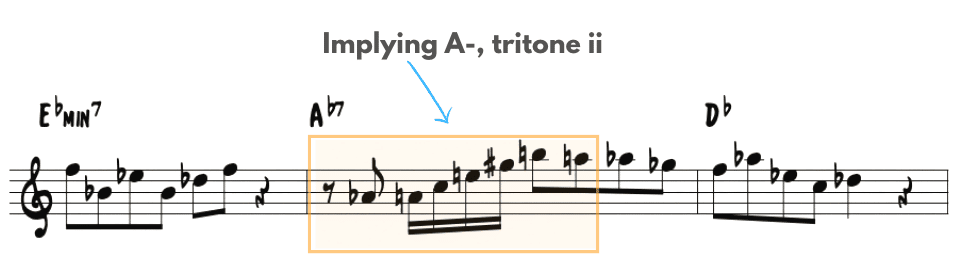

Tritone substitution is a harmonic tactic that jazz musicians often incorporate into their solos, and in The Girl From Ipanema it is often used in place of the diatonic V7 chord in the A section:

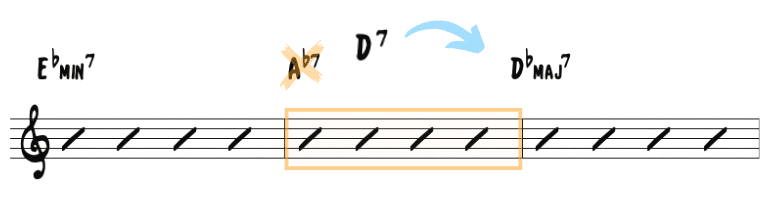

If you’re playing the tune in the key of Db, this would mean implying a D7 chord rather than the diatonic Ab7 dominant chord:

Let’s take a look at how Oscar Peterson implies this tritone sub in his solo, especially over the ii-V:

Over the Ab7 chord, Peterson an A minor-like arpeggio which resolves to Db. But, how is this related to the tritone sub of D7??

Along with the dominant tritone sub of a V7 chord you can also use the tritone ii chord – A- D7 over Ab7, A- over Ab7 – this ends up being a minor chord a half-step above the root.

Along with the substituting a V7 chord with another V7 a tritone away, try utilizing the ii chord of the tritone sub – as a tritone ii-V or simply a ii chord – as another option in your solos.

In Oscar’s line he utilizes the tritone sub by implying the related ii- (A-7) of the tritone V7 chord (D7):

Michael Brecker does the same tactic in his solo as well:

Over the F#7 he plays a G- sound, implying the C7 tritone sub, which then resolves to B minor. Adding this “tritone ii chord” to your musical arsenal will yield a new world of V7 alterations in your solos.

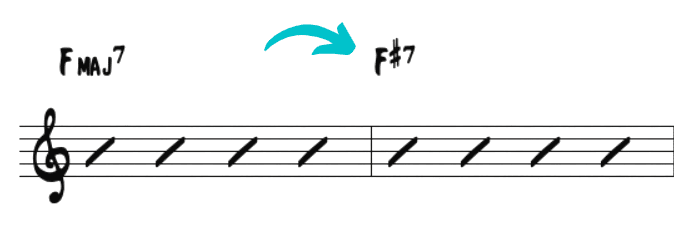

6. Major I to Tritone sub

Along with the V7 chord being subbed in the ii-V, another unique harmonic relationship in the A section of this tune is the I chord moving directly to a V7 sub at the end of the phrase…

This harmonic sequence is also often used as an intro or ending vamp for the tune, so it’s a good idea to ingrain this relationship and have tools to solo over it:

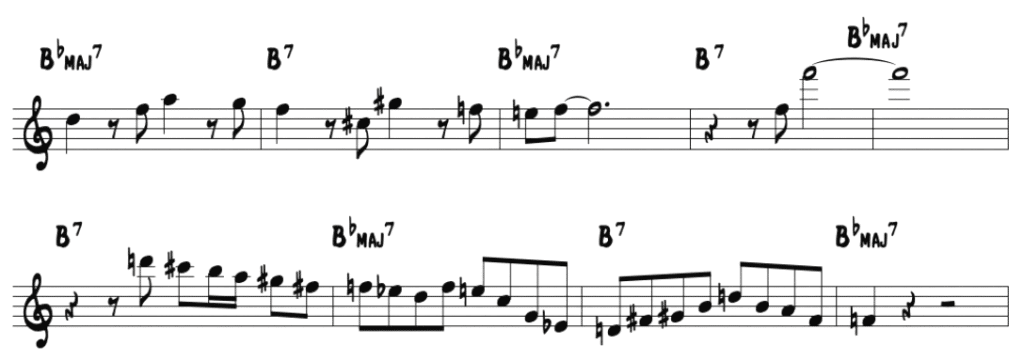

Listen to how Michael Brecker navigates this harmonic relationship at the end of the tune, moving between Bb Major 7 and B7:

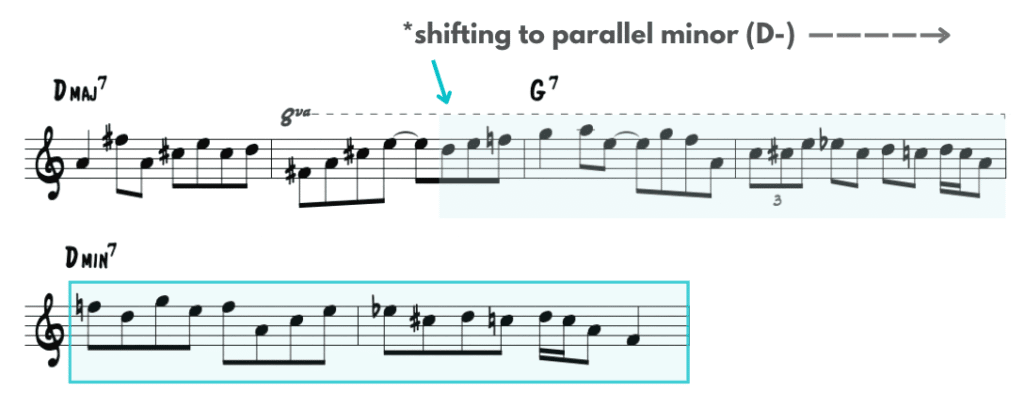

7. Major to minor on the Bridge

As we outlined earlier the Bridge begins with a Major 7 a half-step above the tonic, F# major in the larger key of F. This chord then moves to IV chord and then to the parallel minor…

However, you can imply a Major to parallel minor movement in your solos with a harmonic trick – thinking about the V7 chord in the 3rd measure as minor ii or ii-V:

The result here is F# Major moving directly to F# minor, with the same sound continues in the next bar, greatly simplifying the harmonic approach.

Check out how Oscar Peterson utilizes this concept over the Bridge, (this example is in the larger key of Db, with the bridge in D):

Leading into the G7 chord Peterson switches to D minor material, which he continues for the next four measures:

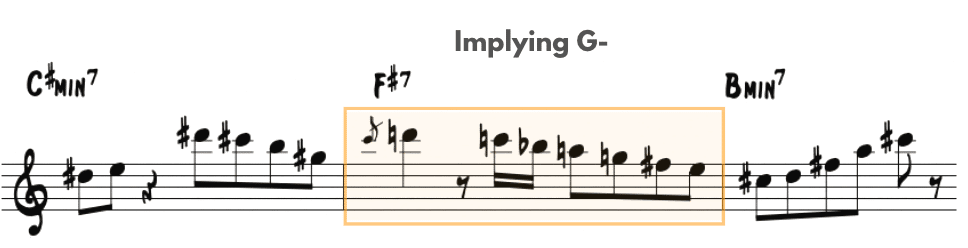

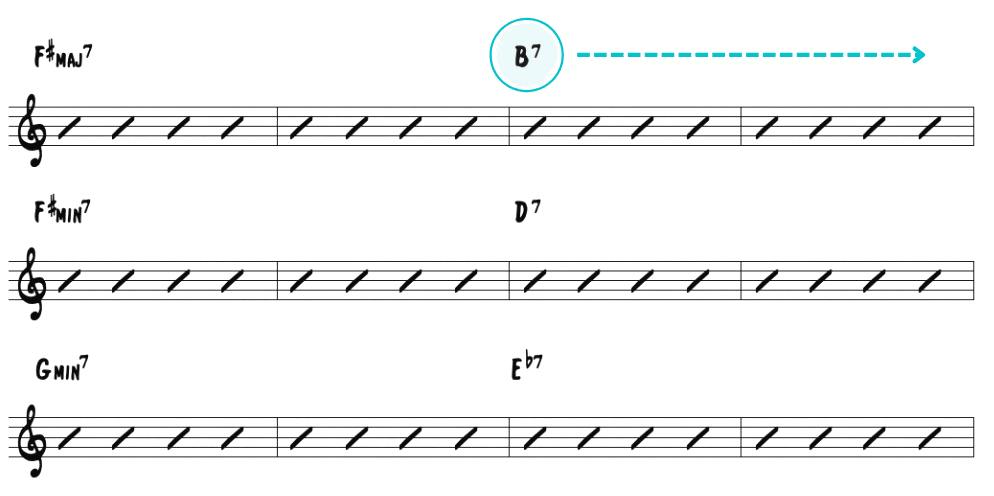

8. Implying ii-V’s on the Bridge

On the bridge you have recurring 2 bars stretches of dominant chords, and these V7 chords don’t all resolve to a related I chord…

Building on the previous concept of implying related chords on V7 sounds, another way to create linear motion on these static dominant chords is to imply a related ii-V progression:

Check out how Michael Brecker does this in his solo to create moving lines on otherwise static chords:

9. The Flat VII7 chord

The bVII7 chord is a common V7 chord substitution that you’ll find in jazz standards leading to the I or iii chord.

This chord, or a ii-V variation of it, is also known as the “back door ii-V,” and you’ll find it in the 11th bar of the Bridge:

As we highlighted above, Brecker approaches this bVII7 chord with ii-V material, but let’s take a look at what Oscar Peterson does here, applying standard dominant language in a different harmonic setting:

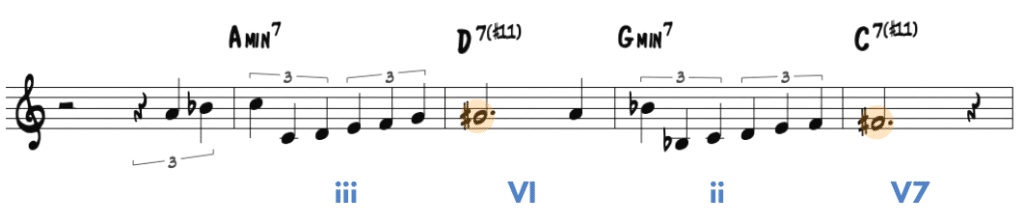

10. The turnaround

The turnaround or iii-VI-ii-V progression is an essential harmonic piece of many jazz standards, and The Girl From Ipanema is no exception…

The final four bars of the Bridge feature a turnaround leading back to the A section:

In your own approach to the progression, you need to make sure you have some melodic and harmonic tactics for navigating this spot in the tune.

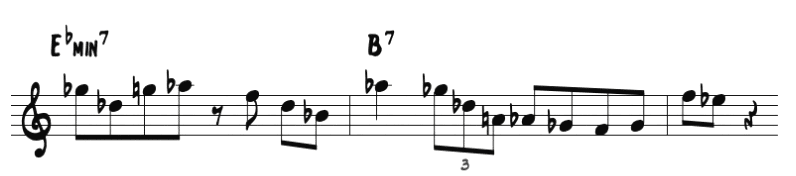

Listen to how Oscar Peterson approaches this progression in the line below:

Here he uses a diatonic triad on the minor iii chord, alters the Bb7chords by emphasizing the #9 and b13 and then opts for an augmented (#5) sound on the Eb- and Ab7 chords.

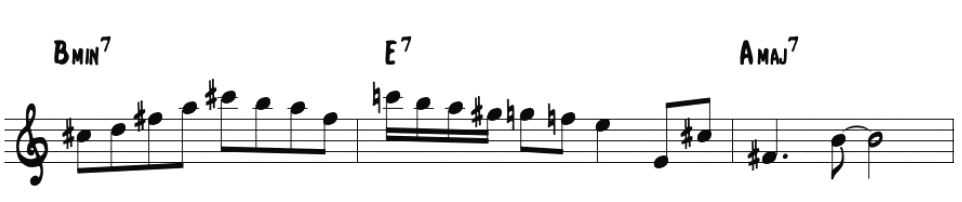

Now let’s check out how Michael Brecker approaches the turnaround in his solo…

In this phrase he uses the ii- of the tritone sub (G-) on the F#7 chord and on the E7 chord (F-), both V7 alteration highlighting the b13 as well as the #9 and b9 sounds.