Many chords are pretty easy to understand. But dominant seventh chords with an assortment of alterations…they’re a whole different animal! What’s with all this b9, #9, b13, #11, b5 stuff! There seem to be a million ways you can alter them and so many available scales. And even when you know the theory, playing over altered dominants in a musical way can remain quite a mystery…

If you feel this way about altered dominant chords, you’re not alone. I remember being super confused when teachers would try to explain all these weird altered notes to me. No matter what advice I took, I couldn’t seem to play over them in a way that didn’t sound artificial, like I was doing math in my head or trying to spell a long word.

And what I realized is that no one had ever laid out exactly what was actually possible with dominant seventh chord alterations, so I was in this mental place where I really didn’t know what was going on or even have an idea of what was harmonically possible.

It’s not until I started to have a mental image of these chords and all of the structural relationships in and between them, that things became a whole lot easier.

In today’s lesson, you’ll get this mental image in your head too, demystifying dominant 7 chord alterations for you once and for all…

Start with seeing the alterations

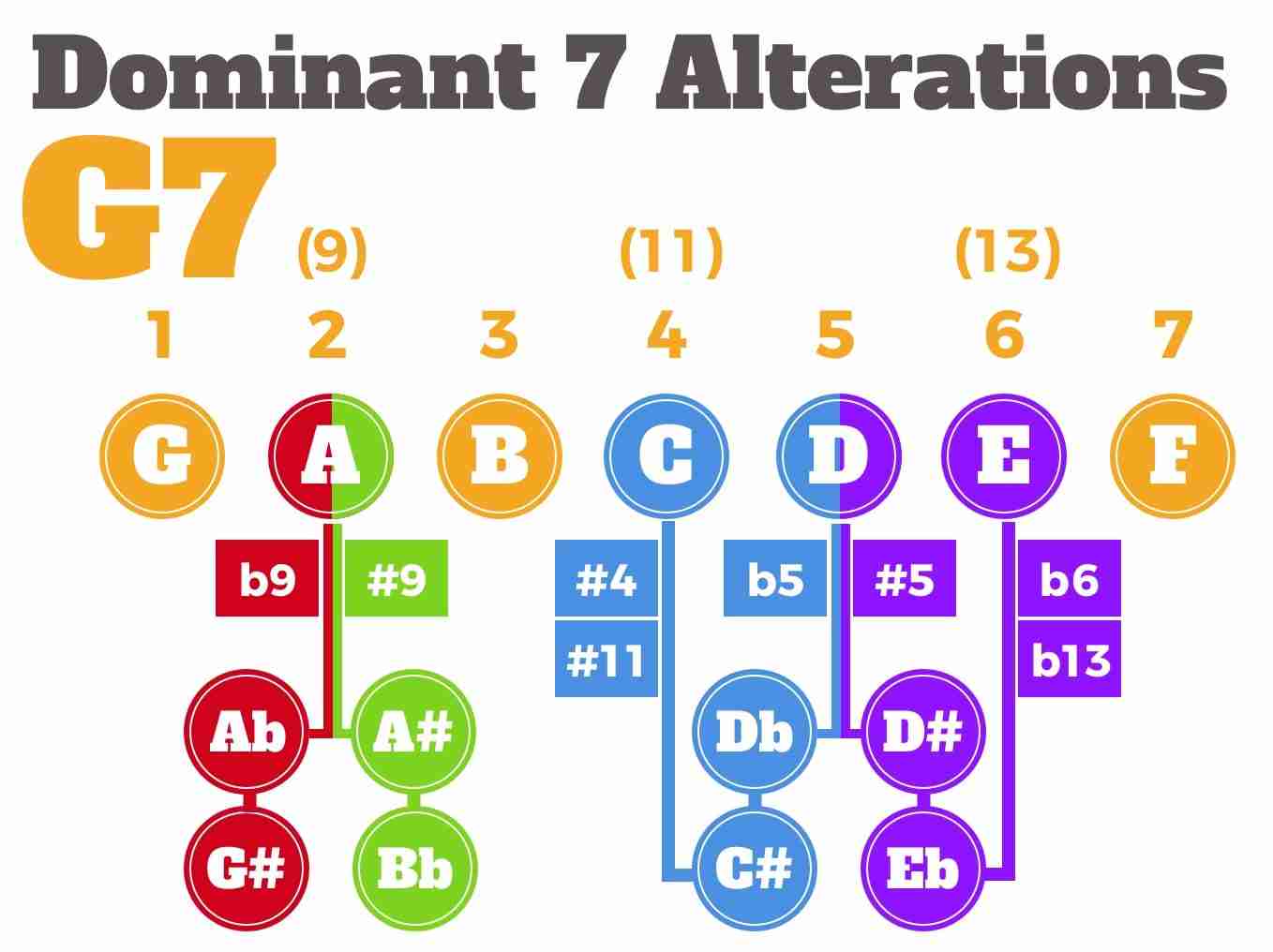

People can talk about dominant alterations all day, but until you have a clear visual example of what’s happening, it can be difficult to sense all the relationships going on.

But what would a visual of all these relationships even look like?

You know when you’re lost in the NY subway, or any other public transit system for that matter, you find that nifty color-coded map of all the lines, and within a few moments you know exactly where you are, where you want to go, and how to get there?

Today, we give you this map for dominant seventh chords…

Although this diagram may look simple, well hopefully it does as that’s the goal, it sums up a ton of relationships and takeaways that you need to understand. Seeing these key points visually should give you the “click” moment you’ve been waiting for where you say, “Oh, I FINALLY get how all this dominant seventh chord alteration stuff works…it’s actually pretty EASY.”

Now, spend some time studying the diagram in order to develop a visual and mental impression of all the relationships in the diagram. Read each one, find how it’s illustrated in the diagram, and let the information soak in:

- There are only 4 “altered” pitches – They are color coded. Until now, you’ve probably known there are only 4, but haven’t seen how they all map out.

- The 9th, 11th, and 13th are the same as the 2nd, 4th, and 6th – These pitches are the same, even though they have different names.

- All 4 of these can be described as “around the 9th and the 5th” – You can lower or raise both the 9th or 5th. Of course, as the diagram shows, you can raise the 11th, which is the same pitch as b5, and lower the 13th, the same pitch as #5. You should be able to think through ALL of these roadmaps to the various altered pitches. In other words, You should be able to think of b5 OR #11. #5 OR b13. Don’t limit yourself!

- For the b9 and #9 there are enharmonic notes (G# & Bb) – You’re not a music theory teacher. You’re a player. If the enharmonic notes are easier to think about, use them. For example, on an A7, a #9 is technically B#, but there’s nothing wrong with thinking of C instead.

- The b5 is the equivalent pitch to #4. The #4 is also called the #11 – These pitches are the same. The rare thing to watch out for is notation that implies a specific voicing. For example, sometimes a composer will specify a b5 instead of a #11 because they do not want a natural 5 in the voicing.

- The b6 is the equivalent pitch to #5. The b6 is also called the b13 – These pitches are the same. Same thing as above though. Notation can specify a specific voicing.

- The root, 3rd and 7th stay “intact” – This of course makes sense because the bass note, the major 3rd and dominant 7th define the chord. As long as they remain, the G7 quality can be heard. If you removed or changed any of these three notes, the chord would no longer be a G Dominant 7 chord. (Well, you could suspend the 3rd and turn it into a sus chord. There are no absolute rules in this music, no matter what anyone tells you!)

- Every chord, despite all it’s alterations, is still just a dominant chord – A major 3rd and a b7. Everything else is simply an added flavor on top of this fundamental structure.

Once you’ve got a handle on these key relationships and takeaways, move on to understanding how the diminished scale relates to dominant 7 chords…

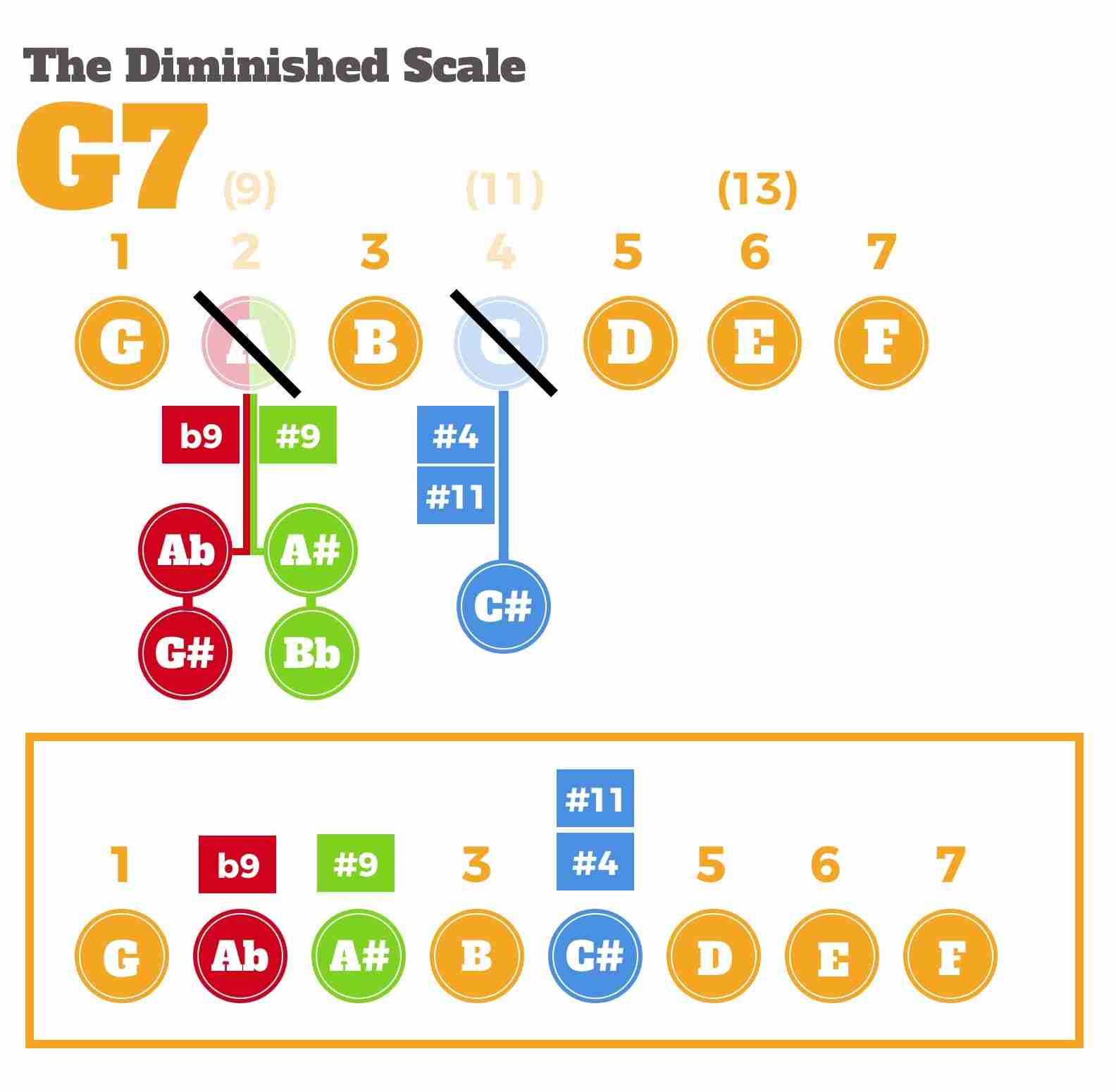

Diminished over dominant – It’s really that easy

When people try to use the diminished scale they think SO much, “Which scale is it? Wait, the half whole one or the whole half?”

They overcomplicate things, often get frustrated, and end up not using the diminished sound over dominant 7 chords at all. Using the diminished scale over a dominant chord is much simpler than you think.

Take a look at the relationships and it all becomes clear:

Has it dawned on you yet that using a diminished scale over a dominant 7 chord is the same as using a b9 & #9, and a #11?

That’s all it is.

Of course, the diminished scale is really cool because it’s an 8 note symmetrical scale that you can form interesting patterns from, but, conceptually over dominant, it’s just a dominant 7 chord with a b9, #9, and #11.

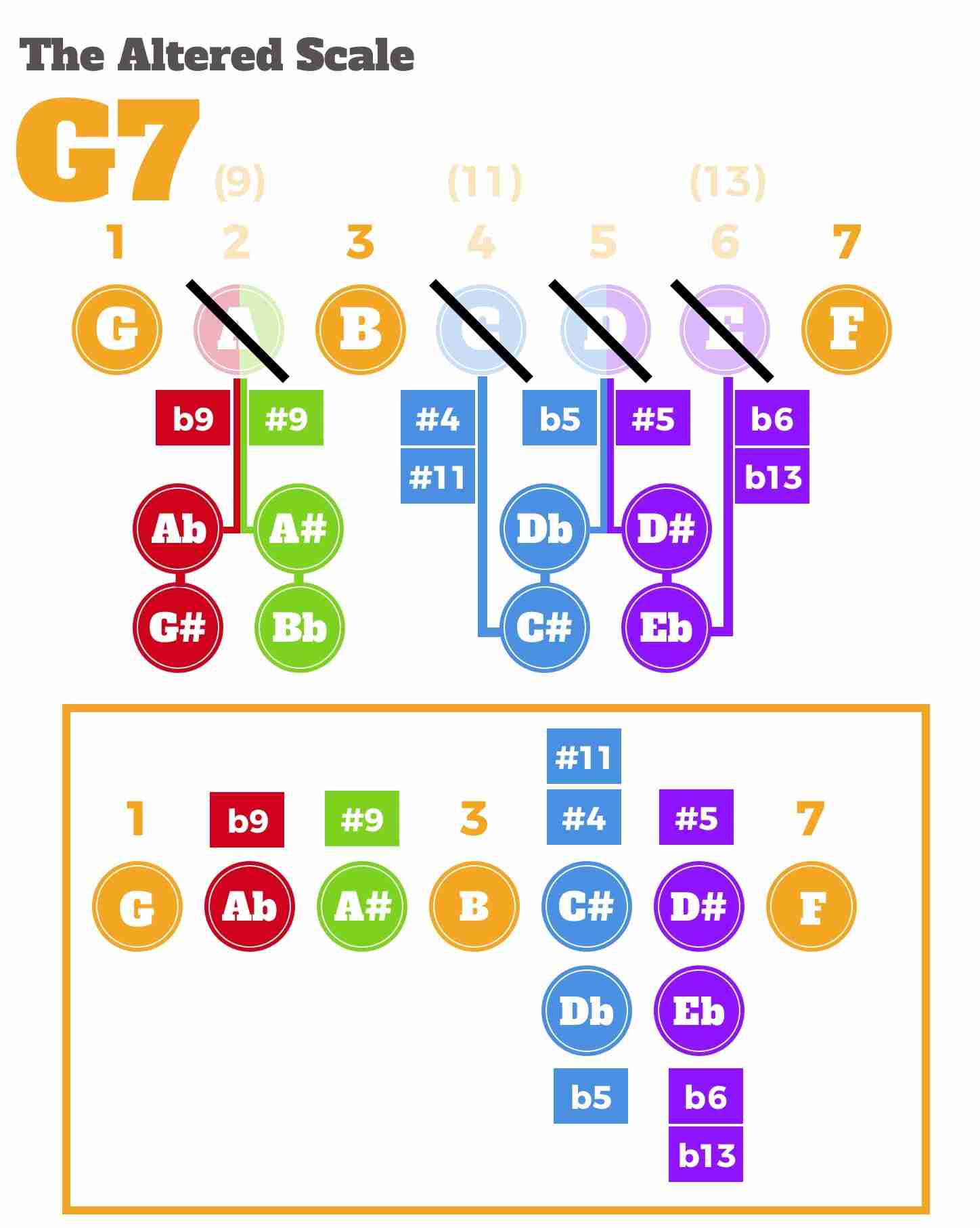

The Altered Scale – A view from above

We’ve written quite a few articles about the altered scale because it’s pretty tricky to grasp. Even once people know the altered scale, it’s even more difficult to use it musically.

The problem is that most people learn the shortcut: go up a half step from the altered chord and play the melodic minor scale.

And after that, their altered scale and chord knowledge stops.

To use the altered scale effectively, you really have to know what’s going on. What’s being altered in the chord? What are the sounds that are happening? What are the relationships? What’s the context?

A view from above gives you the best insight into this scale:

Just looking at this visual, it’s very clear what’s happening.

- The only chord-tones that remain “unaltered” are the root, 3rd, and 7th

- The 9th gets replaced with the b9 & #9 and the 11th gets raised as well, the same way these chord-tones were altered using the diminished scale

- The two pitches 5 and 6 are transformed into two other pitches the b5/#11 and #5/b6/b13.

Once you have a grip on how the altered scale fits into the picture, it’s time to get beyond scales and basic chords, and see what role alterations play in dominant seventh chord voicings…

And if you want to go deeper into understanding the theory behind chords, make sure to check out our course Jazz Theory Unlocked…

Dominant 7 Chord Alterations – Understanding Chord Voicings

So now that you have a subway-map, literally, of dominant chords in your brain, you should have a pretty easy time understanding how dominant chord voicings are constructed and why there seem to be so many different “flavors” of a dominant seventh chord.

A chord voicing is that mysterious group of notes that the piano, guitar, or any other “chording” instrument is playing behind you while you’re soloing. The act of playing these chord voicings in succession as in a chord progression is called “comping”.

The thing is, when someone is comping, it’s up to them what specific chord voicings they use. Sure, the jazz standard you’re playing may specify certain chords, but it’s largely up to the comping instrument to interpret the chords in the moment and respond accordingly depending upon where they hear the music heading.

For example, over a dominant 7 chord heading to the tonic, they might add a b9, or #11. Or they might play a natural 9 with a #5.

It sounds complex, but when you break it down, it’s really not.

Let’s take a look at how easy it is to construct a dominant 7 chord voicing with some alterations.

It all goes back to two things:

- Which notes you include/omit in the chord voicing – In our examples, we’ll include: 1, 3, 7, 9, 13

- What order you play the notes in – In our examples we’ll make the order: 1, 7, 9, 3, 13

We’ll construct three different dominant seventh chord voicings.

In all of our chord voicings we will include the root, the 3rd, and the 7th along with either a natural or altered version of the 9th and 13th.

By keeping the voicing in the same structure but gradually altering the 9th and 13th, you’ll get to hear exactly what’s going on.

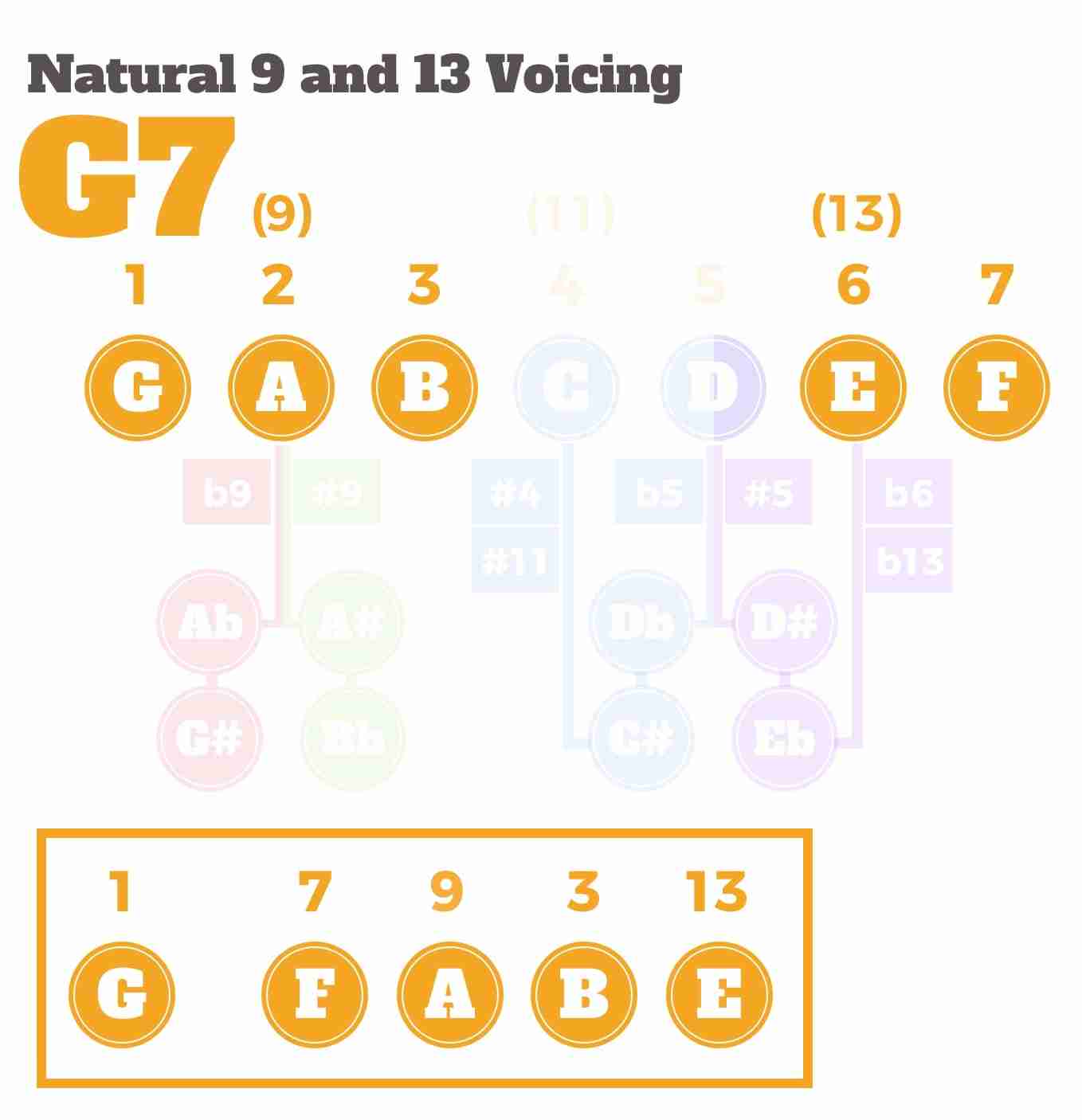

Dominant 7 Chord Voicing with a natural 9th and natural 13th

Have a listen to this voicing.

In this first chord voicing, it’s all unaltered notes. The root followed by 7, 9, 3, and 13 on top. Now, this doesn’t mean you can’t alter notes in your improvised lines.

It means that the sound going on behind you uses a natural 9 and natural 13. You need to learn to hear that specific flavor of a dominant chord and how your melodic lines fit with it to best know how to play over that sound.

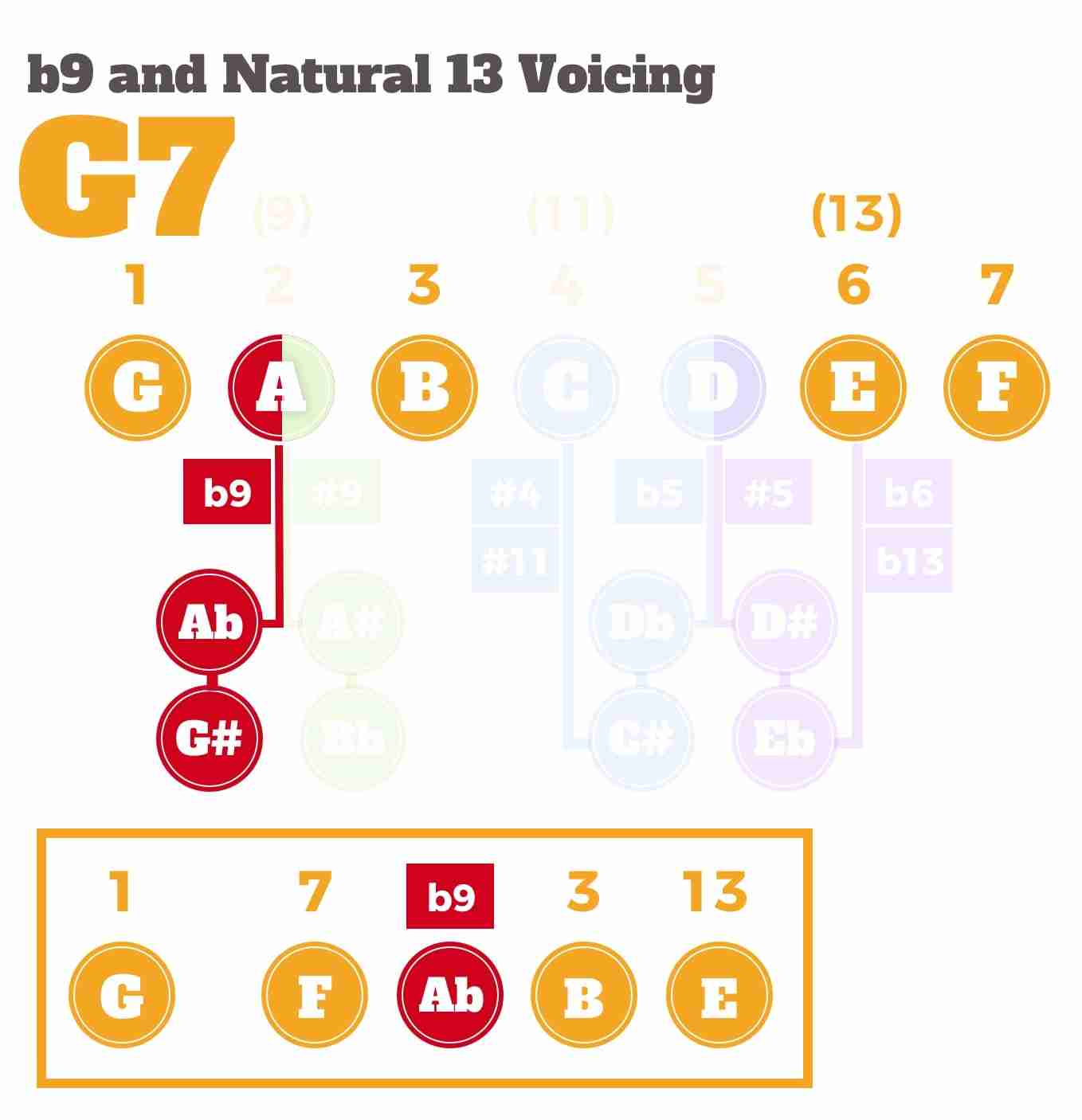

Dominant 7 Chord Voicing with a b9 and natural 13th

In this second chord voicing, all we’re doing is flatting the 9th from the previous voicing. The root followed by 7, b9, 3, and 13 on top.

In classic jazz music theory and chord-scale relationships, this sound corresponds to a diminished scale because it uses the natural 13 and not the b13 or #5.

This is good information to know, however, it’s not a rule that every time you hear this sound you have to use the diminished scale. In fact, you can easily play a b13 over this sound and sound great if you know how to use it in terms of jazz language and you can hear how to resolve it. So, know the theory, but don’t be limited by it.

Playing a diminished scale over this sound is but ONE perspective to play over it. Try others. Experiment. As much as we all love the DMV, you don’t need a license to be creative 😉

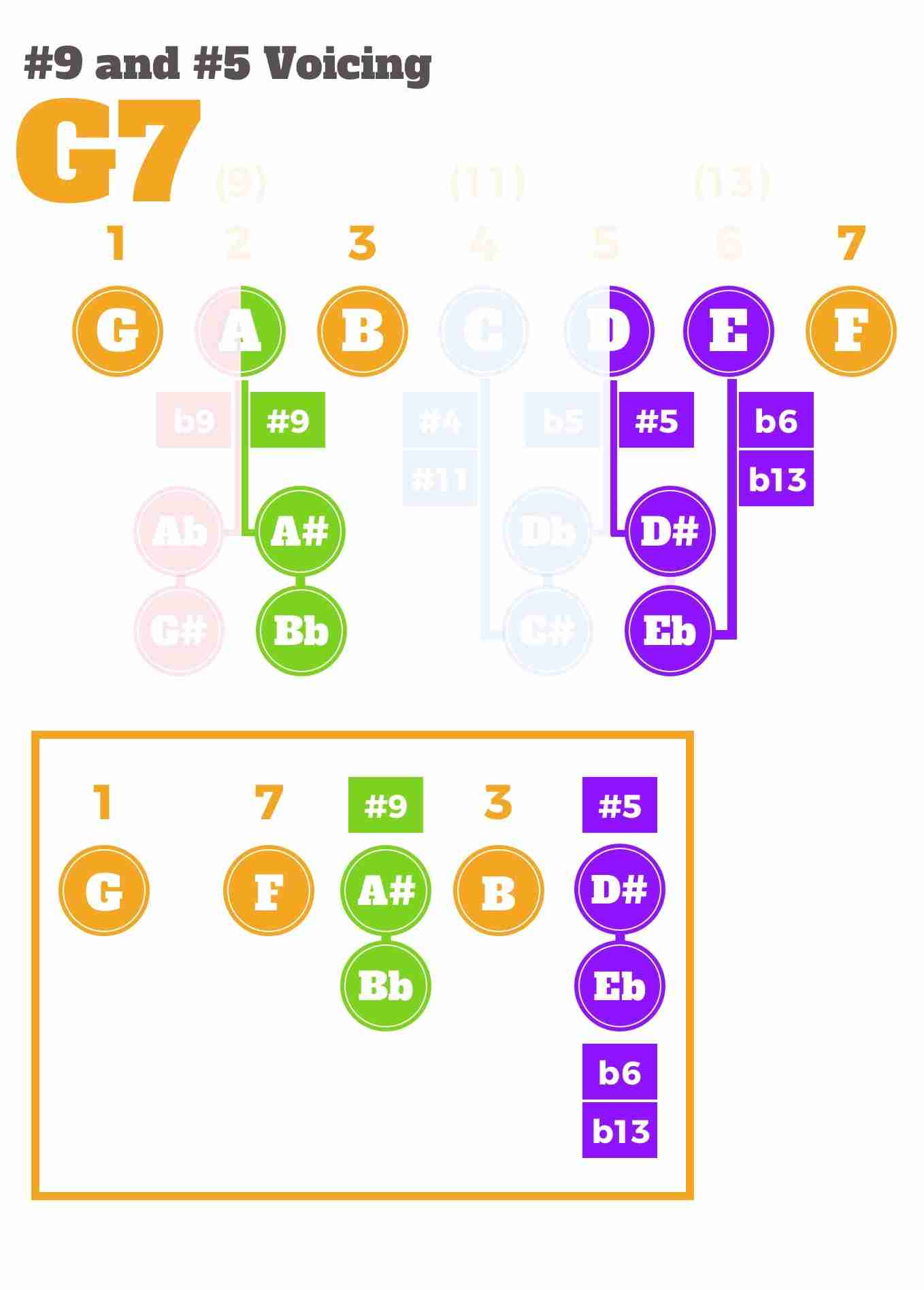

Dominant 7 Chord Voicing with a #9 and #5

In this last chord voicing, we’ll flat the 13th from the previous voicing. The root followed by 7, b9, 3, and b13 on top.

Notice how all three of these voicings sound quite different, but are still dominant chords?

Now for this sound, jazz theory calls for the altered scale because it contains the b13/#5. But, just as I said before. Know the theory but also know that there are plenty of other ways to think about and play over this sound.

Remember. It’s a SOUND. That’s right, a sound is going on behind you while you improvise. A scale choice does its best job to guide you to the strong notes of the voicing, however, by conceptually knowing and having the ability to hear the chord voicing, you can craft lines that are structured around the chord-tones in the voicing without relying so heavily on jazz scale or theoretical knowledge.

And if you really want to get into hearing the specifics of chord voicings, The Ear Training Method goes through a ton of them in a systematic way.

Dominant Seventh Chord Alterations Demystified

Sometimes there are things that no matter how many times somebody tells them to you, they’re still confusing…

The solution: find a totally different way to conceptualize the information.

And when it comes to jazz improvisation, visuals can help explain relationships to us and give us a better idea of what’s happening, whether it be harmonic, melodic, or even rhythmic.

It’s my hope that the diagram I’ve shared with you today sheds some light onto the mysterious altered dominants for you.

Spend some time with the subway-map of dominant 7 alterations and make sure you’re seeing all the information that’s there. Then:

- Work through the first diagram in all keys – Try writing it out in another key, or just saying the notes aloud in a new key

- Quiz yourself on quickly knowing what the alterations are for every dominant chord. Start with the b9 and work through all the alterations in all keys. Our Visualization Course takes this idea to a whole new level if you need some extra guidance.

- Mentally practice diminished over dominant – Think slowly through every dominant chord using the diminished scale by substituting the 9th for the b9 and #9, and raising the 11th. Connect the relationships in your mind.

- Mentally practice the altered scale – Think slowly through every dominant chord using the altered scale by substituting the 9th for the b9 and #9, and raising the 11th as you did with diminished. AND substituting the 56, for b5/#11, #5/b13

Have fun exploring all the variations of altered dominant chords. They truly are one of the most beautiful sounds in this music and learning to understand, hear, and play over them will add a whole new dimension to your playing!