Minor harmony is everywhere in jazz. Whether you’re playing a tune in a minor key or a jazz standard that shifts to the relative minor for a section, you need a solid understanding of how minor harmony works in jazz. From this understanding, you’ll memorize jazz standards faster, understand chord progressions on a deeper level, and improvise with more confidence and clarity.

Compared to major harmony, everyone seems to get totally lost when it comes to minor harmony. It’s as if their teacher said…Ok, here’s The Dorian mode…now you’re all set when it comes to minor…But there’s so much more to minor harmony…in fact, there’s a whole way that chords FUNCTION in a minor key!

Like most people, I can recall running into a million problems when it came to minor keys…I played minor tunes like Autumn Leaves, Alone Together, and Softly as in a Morning Sunrise for years without really understanding how progressions in minor actually worked…

And I played jazz standards like I Hear a Rhapsody and My Shining Hour, not even realizing the important relationship between the major and minor key centers within those tunes.

I struggled to understand where a minor ii V came from – Why are the chords in them seem so different from one another? Why are they not like major ii Vs where the chords obviously share the same underlying key center?

Even a minor blues didn’t quite make sense – How does the IV chord become minor? Why do both the I and IV chords use The Dorian mode, isn’t that for ii minor chords?

But that’s just how it goes…

We get so caught up in memorizing chords to tunes without understanding the HOW and WHY behind them, that we miss out on a deep understanding of how harmony actually works.

And it’s exactly this understanding of harmony that will liberate you from needing to memorize a ton of chords simply by rote. With the knowledge of why a chord progression is the way it is, you give context and meaning to every chord and how the chords function as a cohesive unit.

But why is it so difficult to get this understanding with minor harmony?

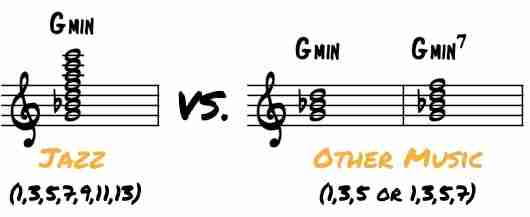

When it comes to playing jazz, minor harmony is not as easy as you might expect. You see, the way we think about harmony – especially minor harmony – as a jazz musician is slightly different than other styles of music…

Really? Jazz is different?

Yes. Despite what anyone says, jazz has harmonic complications to deal with that most other music styles do not have…

In this lesson we’re going to get into these harmonic complications and a whole lot more, starting from the very beginning and building minor harmony from the ground up.

Today we’re going to look at the intricate details of:

- How to create minor harmony

- Where each chord comes from in a minor key

- Where common minor progressions come from

- How to understand the subtleties of the chords in a minor key

- Why there are so many minor scales and their various roles

- Why the Tonic minor chord gets special treatment

- Why the V7 chord in minor becomes altered

And a whole lot more!!

But before we dive into minor harmony, let’s recap some of the essentials of functional harmony…

What is functional Harmony?

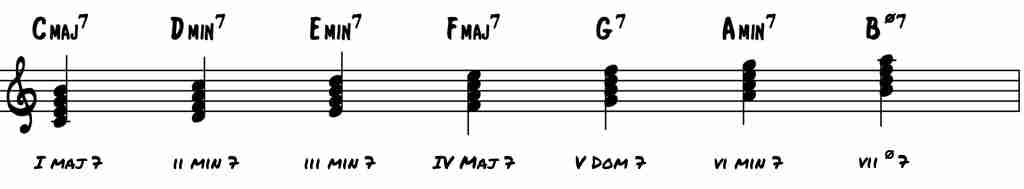

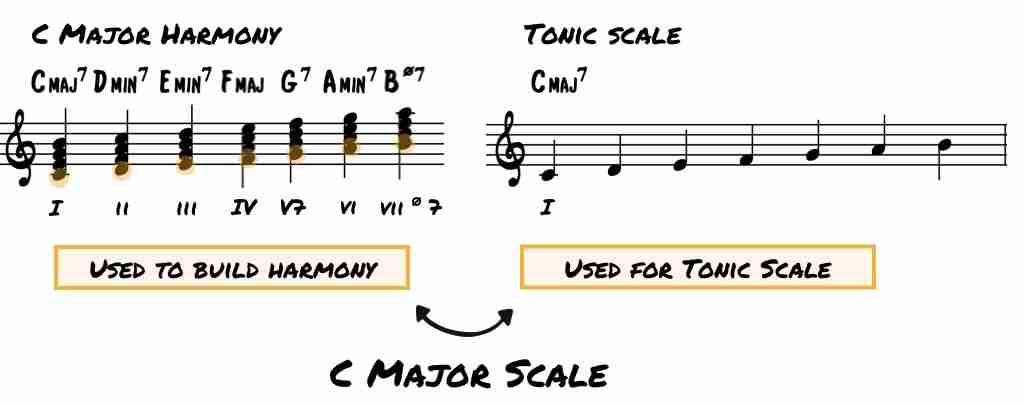

Let’s jump into a simplified version of what functional harmony is and why it’s so important. To create functional harmony, you take a scale and “harmonize it” by building seventh chords from each note of the scale, stacking diatonic 3rds. Diatonic means “within the scale”

When you do this, a set of chords emerges. This set of chords creates a “harmonic context” that’s referred to as a “key”.

So a “key” or a “key center” is actually something that is created from this process of building chords from a scale and it’s exactly this process that makes harmony functional. For example, the chords that emerge from harmonizing a C major scale create a set of chords that function within the key of C major.

The first chord in the set, the “Tonic” chord, is the “home base” of the key – all of the other chords function in relation to the Tonic. For instance, the key of C major has the Tonic chord of C major 7 and all of the other chords function in relation to C major 7.

The whole reason chords function a specific way within a key and progress to specific places is because the key center was created by this process of harmonizing a scale.

Within the context of a key, each chord contains a degree of tension or resolution – some chords have a stable sound and others have an unstable sound.

As one would expect, the sound of unstable chords “wants” to move toward stable sounds. This is what causes chords to naturally move in a specific way within the context of a key – it’s why chords progress and why we call them chord progressions.

Understanding functional harmony and all that’s included within it is very important to jazz musicians because it’s the foundation for where all the chord progressions to the classic jazz standards come from. The better you understand functional harmony, the better you’ll understand jazz standards…

For a refresher on functional harmony and how this process is applied to major harmony, make sure to read through this lesson on harmonizing major scales and creating major harmony before you get into how to do this with minor.

Once you’re ready, let’s get into how minor harmony works…

How to create minor harmony: Relative major & Relative minor

Creating and understanding the chords that function in a minor key is very similar to understanding how they are created and function in major.

To begin, let’s quickly outline the process of “Harmonization” we talked about:

- Choose a key we want to define, then write out the scale from the tonic of the key that we will use to build chords from

- Build seventh chords from each note of the scale by stacking diatonic 3rds. Remember this is called “harmonizing” the scale.

- Label each chord based upon the chord quality and numbered position it occupies within the key. This is what it means to define “chord function” within a key.

So, the first challenge is to choose which scale we are going to harmonize to define a minor key.

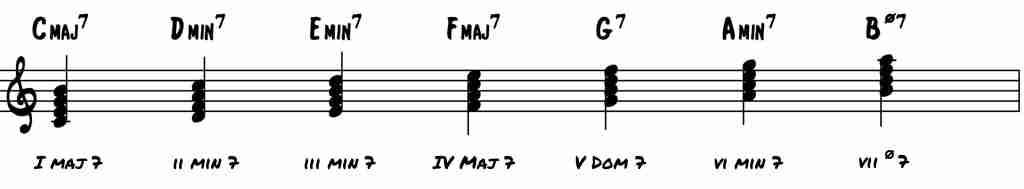

To understand where minor comes from and to discover the initial scale that we’ll harmonize, we first have to go to major harmony…Take a look at a harmonized C major scale – Our functional harmony in the key of C major:

Now, do you remember what makes this whole set of chords function in the key of C major? They function in C major because the chords revolve around our Tonic chord – the I chord, our “home base.”

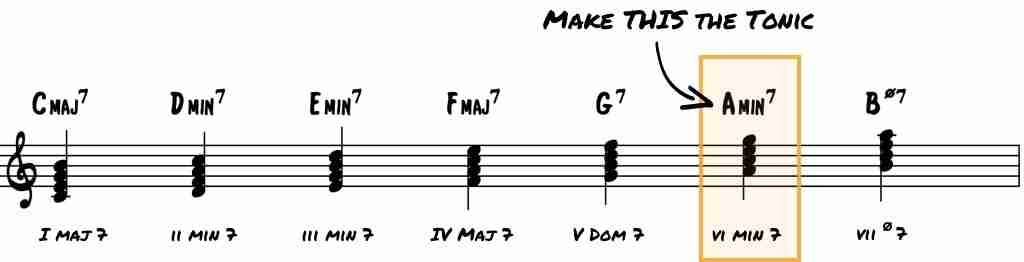

So, if we wanted to transform our home base into a minor key instead of a major one, we would have to make a minor chord and scale our Tonic instead of C major.

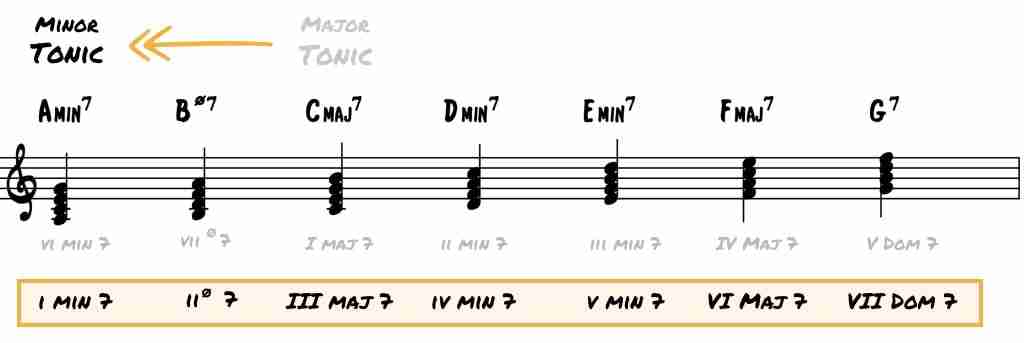

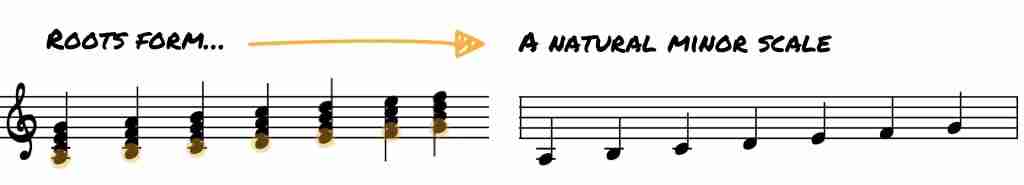

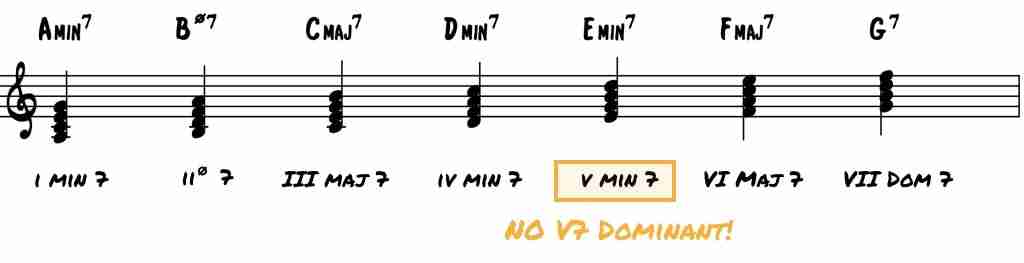

To do this, we shift the entire scale and all the chord chord functions a minor 3rd down to the relative minor, so the Tonic becomes “A minor.” Then we renumber the functions of each chord in relation to the new Tonic (The One Chord):

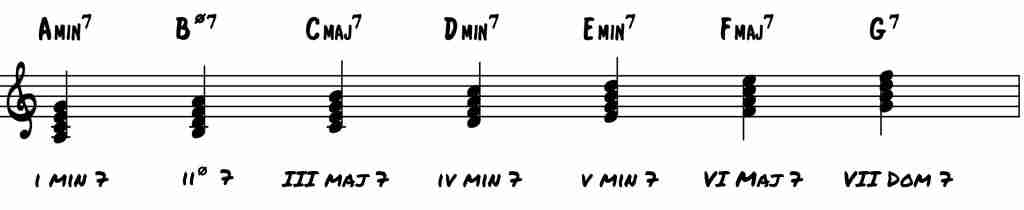

Now the scale the chords are built from (The scale formed by the roots of the chords) is not C major, but A Natural Minor, the 6th mode of a C major scale, also called the Aeolian mode.

As you can see, when we build seventh chords from each of the notes in A Natural Minor, what we call “harmonizing the scale”, we’ll arrive at the exact same chords that we had from C major…the only difference is now the chords function in relation to our new tonic, A minor.

This harmonized scale is where the bulk of minor harmony in jazz comes from – the Natural Minor Scale.

Coming from a jazz theory context where Dorian and the Melodic Minor scales play such key roles, it’s very important to understand that in terms of classic harmony, minor keys are born from Natural Minor, not Dorian or Melodic Minor…

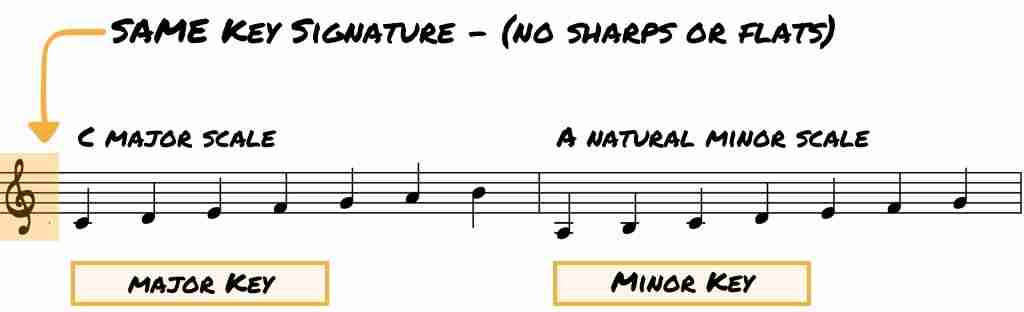

When people talk about a song in the key of A minor, this is the minor they’re talking about – It’s the same key signature as C major, but the key is minor instead of major.

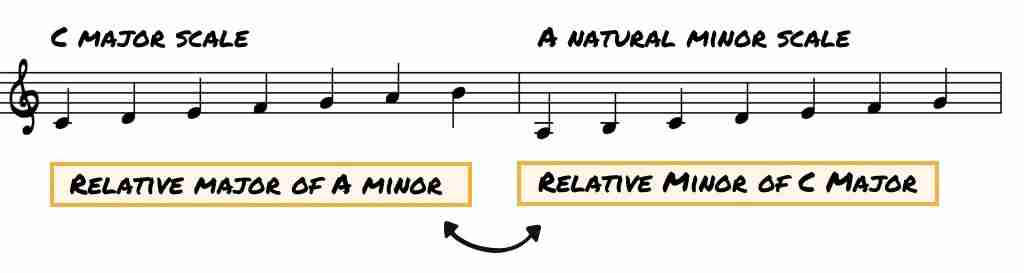

In fact, this particular relationship between major and minor is so important that there’s even a special name for it: Relative Minor and Relative Major

For example, A minor and C major are relative to one another:

Memorizing all the relative minor and relative major relationships is a valuable piece of information. Many jazz standards move between these two places.

Now, look at the chords that came from harmonizing our Natural Minor scale and see if you notice anything that’s missing…

Do you see anything that seems a little strange?

If you noticed that the V chord is a minor 7 chord and not a dominant 7 chord, then you’re on top of things.

Chords that function as a V chord in jazz are usually dominant 7 chords because this is where the interesting tension lies…Clearly it lacks some essential ingredients, which is why the Natural Minor scale alone is rarely used for minor harmony in jazz or even other musical styles…

So harmonizing the Natural Minor was our first step into minor harmony, but it’s not complete!!

Where the V7 chord comes from: The Harmonic Minor scale

What’s the problem with a V chord that’s minor instead of dominant?

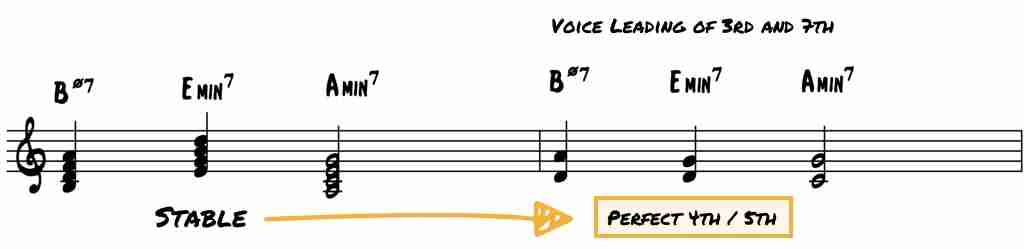

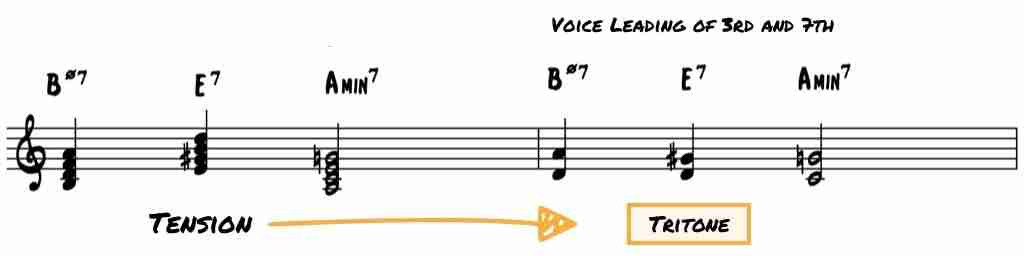

When the V chord is a minor 7 chord, as we get from harmonizing the Natural Minor scale, instead of a dominant 7 chord, it lacks the intervallic tension needed to drive our ears toward the tonic chord in a V to I progression – a progression we encounter everywhere in jazz…

You see, the tritone interval between the 3rd and 7th of a dominant chord creates the intervallic tension that our ear picks up on within a dominant chord and wants to hear resolved.

A minor 7 chord does not contain this interval, so it doesn’t have the harmonic tension necessary for an effective V to I in jazz.

We want the V7 chord in the key of A minor to be E7 instead of E minor 7 so it contains the tritone and builds the necessary tension from V7 to I…

So if we want this V7 dominant sound in minor keys, where can we get it from??

Enter the Harmonic Minor Scale.

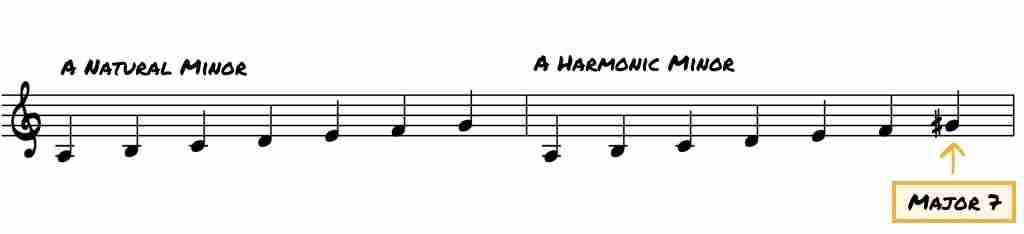

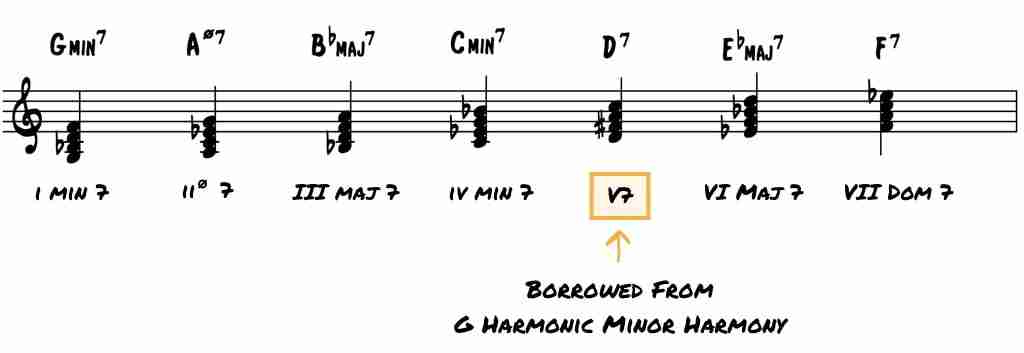

It’s called the Harmonic Minor because it’s commonly harmonized to create chords in a minor key, but it is often used for melodic purposes, too. The ONLY difference between the Harmonic Minor and Natural Minor scales is the major 7th.

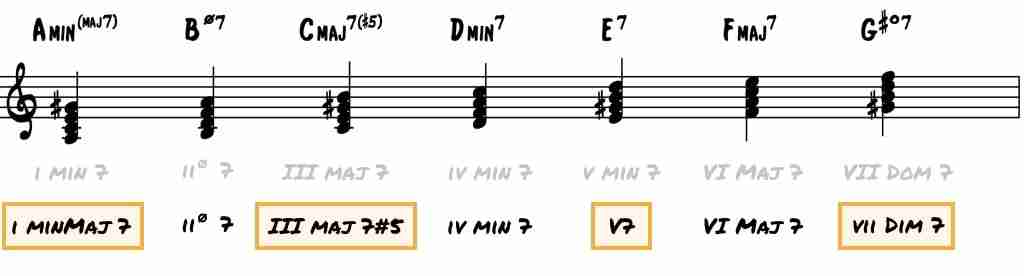

This one modification (The G# ) changes 4 chords in our Natural Minor scale harmony…

- I min 7 becomes I min Maj7, A min 7 to A minMaj7

- III maj becomes III Maj7 #5, C Major 7 to C major 7 #5

- V min 7 becomes V7, E min7 to E7

- VII 7 becomes VII diminished, G7 to G# diminished 7

This is where the V7 dominant chord comes from in minor keys…from harmonizing the Harmonic Minor scale…

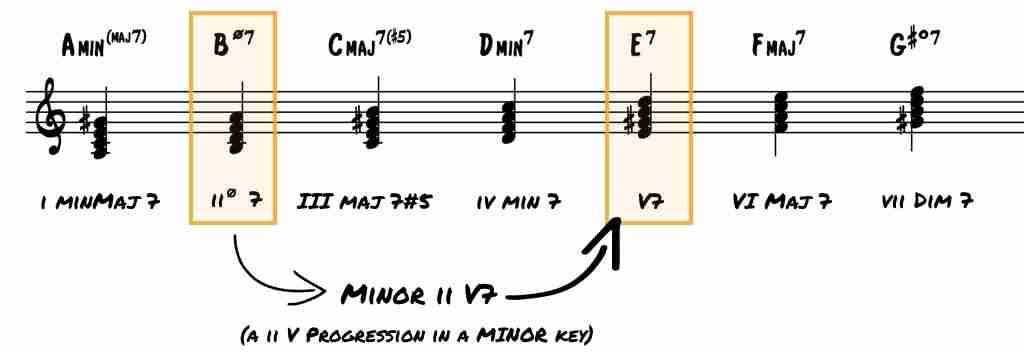

And this is where the minor ii V7 comes from as well:

But one thing to realize is that V7 in a minor key is slightly different than V7 in major key…

How V7 is different in a minor key

In jazz, when V7 is moving to I, whether it’s in a major key or minor key, the chording instrument can add alterations to the chord voicing.

But if you’ve ever worked on tunes containing minor ii V7s before, you’ll notice that when you see a V7 chord in a chart, or hear a V7 chord functioning in a minor key, it’s pretty much always notated and played with alterations.

Why are dominant alterations a CHOICE in major keys, but seem REQUIRED in minor keys??

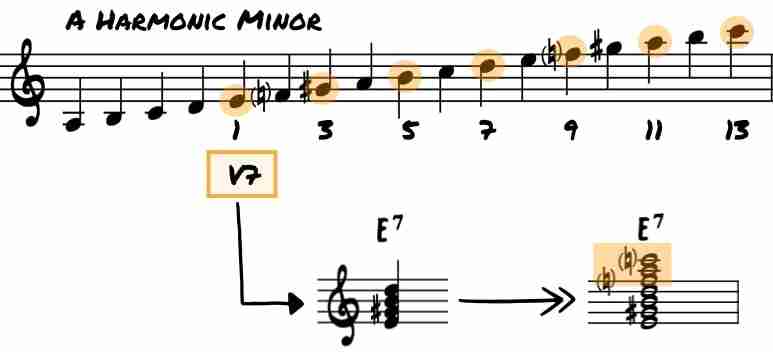

To understand why V7 in a minor key tends to be altered, we just have to look at the upper structure of the chord – 9, 11, 13.

We simply take our V7 chord (E7) that we got from harmonizing Harmonic Minor and extend the chord-tones up to the 13th, and this is what we get…

Notice that the extended chord has a b9 (F), a natural 11 (A), and a b13 (C). The upper structure of this chord contains altered chord-tones that imply the use of an altered chord voicing.

The natural 11 is never included in the voicing because the natural 11 on a major or dominant chord within a chord voicing conflicts with the sound of the major 3rd and would only be used in sus chord voicings.

But the b9, b13 (same as #5) and possibly the other two of the four possible alterations, a #9 or b5 could easily be included as well.

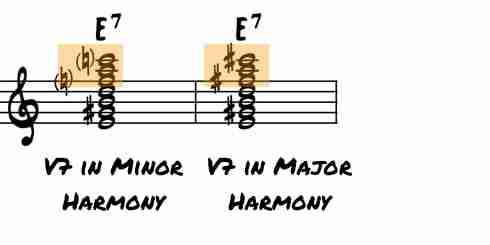

So, to contrast minor with major, if we look at the underlying harmony of a V7 chord functioning in a minor key versus a V7 chord functioning in a major key, we can clearly see that in minor the alterations exist in the chord extension, whereas in a major key, they don’t…

This is why altering the V7 dominant chord in minor keys is generally seen as required, whereas in major, the comping instrument has a choice whether to alter the natural chord-tones or not.

This subtle point, that a V7 chord functioning in major is actually slightly different than a V7 chord functioning in minor, took me years to understand. Coming to grips with the upper extensions of the chord structure and where they come from will result in a much deeper understanding of V7 chords in a minor key.

Now, moving back to harmony…our V7 chord in a minor key as we’ve been talking about, comes from Harmonic Minor harmony, not the Natural Minor harmony that we began this lesson with…

Some resources might tell you that minor harmony comes solely from the Harmonic Minor scale OR the Natural Minor…

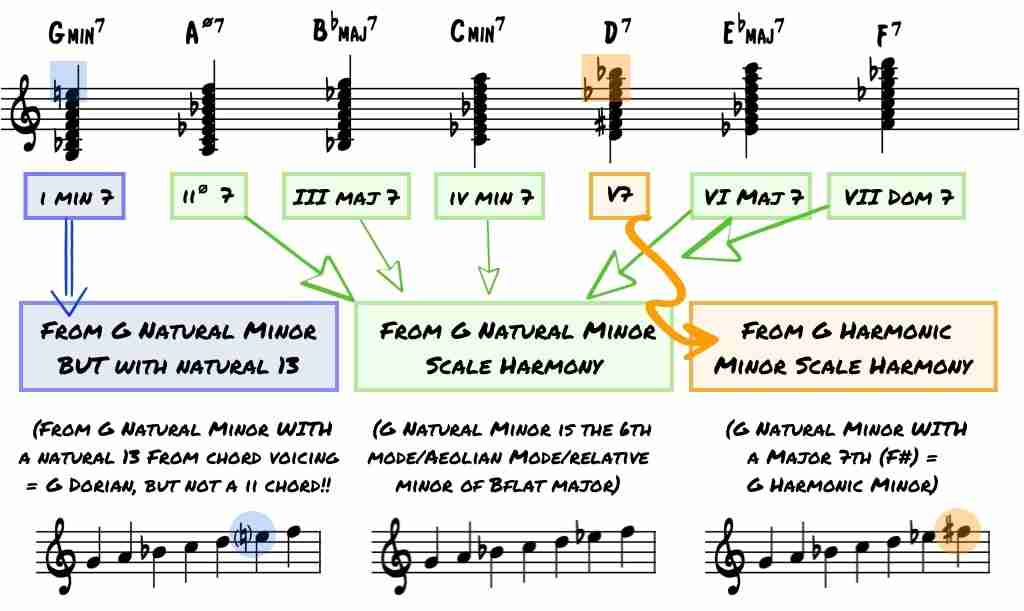

But more often than not, especially in jazz, compositions will use some chords from harmonizing the Natural Minor scale, and some chords from harmonizing the Harmonic Minor scale.

The music theory name for this is called Chord Borrowing and it opens up a world of possibility…

Minor Harmony in Jazz: Chord Borrowing

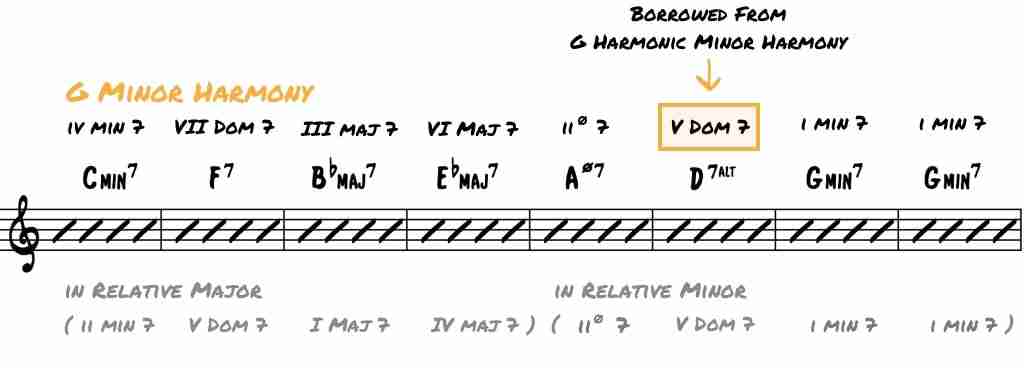

If you transcribe a bunch of chord changes to jazz tunes in a minor key, or tunes that move between the relative major and minor keys, you’ll quickly realize that for minor, jazz tends to use mostly chords from harmonizing the Natural Minor, and then borrow some chords by harmonizing the Harmonic Minor scale…

Chord borrowing is exactly what it sounds like…you BORROW chords from another scale that starts on the same pitch, music theory calls this “parallel keys.”

Some examples of borrowing from parallel keys are:

- Borrowing chords from C Natural Minor, when composing in C major

- Borrowing chords from C Harmonic Minor, when composing in C Natural Minor

This means that even when strictly following music theory guidelines, you can use TONS of chords outside of the harmony created by harmonizing a single scale because you can borrow any chord from any parallel key!!

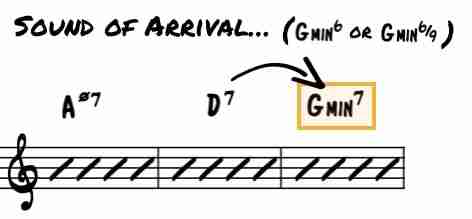

Most jazz tunes use a mixed concept of minor harmony, using chords that emerge from both the Natural Minor and Harmonic Minor harmony. For example, take a listen to Chet Baker play Autumn Leaves:

Now like we say all the time, when it comes to jazz…there’s never one single correct way to look at anything!!!

You can think of the entire first 8 bars functioning in G minor, which is how it probably sounds to most people…or you could think of the first 4 bars in the key of Bb major and the next 4 bars in the key of G minor…

But no matter how you think about it, what’s important is that you understand the relative major/minor relationship between Bb major and G minor, and that all of these chords could come from Natural Minor harmony except the V7 in the minor key, which is borrowed from Harmonic Minor harmony.

When writing in minor keys, or major keys that move to the relative minor, this formula that uses the chords from Natural Minor harmony and borrows the V7 chord from Harmonic Minor harmony is extremely common for jazz composers to use:

And while you could theoretically borrow a bunch of chords from Harmonic Minor, most of the time when dealing with standards, it’s primarily just the V7 chord. You may sometimes encounter the VII diminished chord or the I minor-major 7 chord, but the V7 is the one that will be there pretty much all the time.

And just like the V7 chord in minor gets some special treatment, the Tonic minor chord has a few harmonic complications to deal with, too…

The Tonic Minor Chord and Scale in Jazz

Next we’ll talk about a tricky issue that has to do with the chord-tones and scale of the Tonic chord in a minor key.

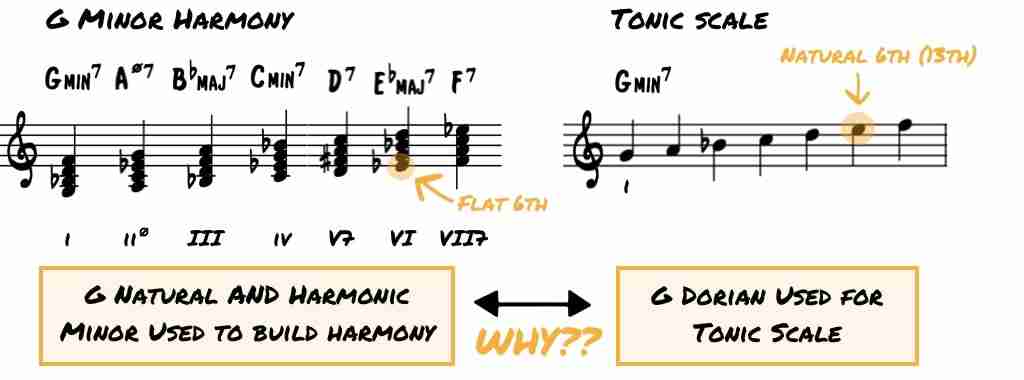

You might assume that because Natural Minor and Harmonic Minor are used to create harmony in a minor key, that they’d also be the appropriate scale for the Tonic minor chord. Typically, the scale used for the Tonic of a key is the scale used to to create and define harmony for the whole key, as with a major key and the major scale…

But on the flip side…in a minor key in a jazz context…neither the Harmonic Minor or Natural Minor scales are used as the Tonic scale…

Why is this, that in jazz, Tonic minor chords don’t use either one of the scales that we used to build minor harmony from?

Well, here’s the thing…in jazz the upper structure chord-tones 9, 11, and 13 are implied with every single chord, no matter how the chord symbol is notated.

So, in jazz, the chording instrument in the group will typically voice each chord to include upper structure chord-tones and altered notes – 9, 11, 13 or their altered counterparts b9, #9, #11 (b5), b13 (#5).

This sets jazz apart from most other music.

Other genres do NOT add these chord-tones so casually and in the moment! You see, in other music the 9th, 11th, and 13th are of much less concern, unless a chord symbol specifically notates it. This is a major difference between jazz and other music that so few people realize…

So what does this mean in terms of Tonic minor chords?

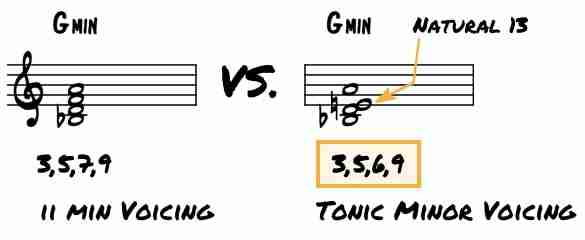

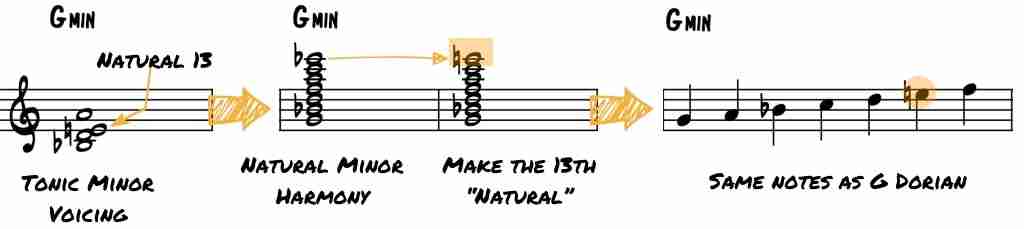

It means that the chording instrument will add some combination of 9, 11, and natural 13 to the voicing of Tonic minor chords, and there’s a specific reason that Tonic minor chords are commonly voiced with a natural 13th…

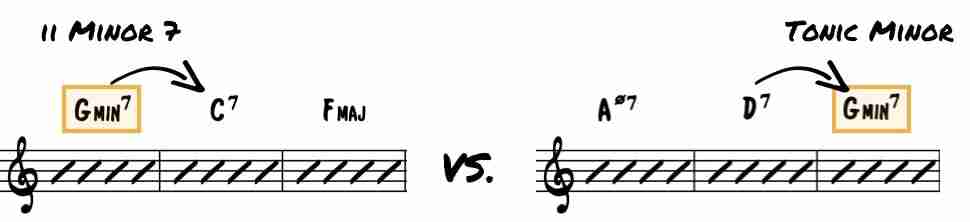

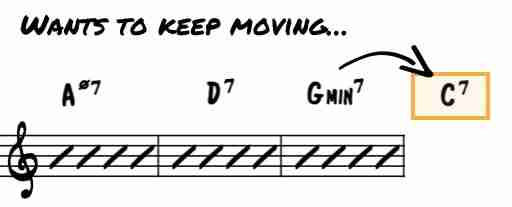

When it comes to Tonic minor chords, we want them to sound different than a ii minor 7 chord that precedes a dominant chord, as in a ii V I progression. In other words, we do not want our Tonic minor chord to sound like it wants to progress to a V7 chord like a ii min 7 chord does…

To distinguish these sounds and make a Tonic minor chord sound more like an arrival point, a “home base”, the natural 13th (the 6th), along with the 9th are commonly added to the voicing…

Listen to what this Tonic minor voicing sounds like…

Now, instead of the Tonic minor chord sounding like it’s going to continue to progress as illustrated in the following example…

It will sound like an arrival point like this…

The chord is voiced like a minor 6 or minor 6 9. And, be aware that it may still be notated as minor 7 chord because of the short-hand nature of jazz chord notation. Remember, upper structures (9,11,13) are implied with chords in jazz.

So, because of the way we voice Tonic minor chords specifically in jazz, the melodic notes that sound most consonant over this chord include the natural 13th instead of the b13th.

Looking at our Natural Minor Harmony, we have to raise our b13 to natural 13…and the result is the common minor scale we jazzers know so well..The Dorian Mode:

Pretty weird, huh? That the Tonic chord doesn’t use the scale(s) you build minor harmony from…

This single issue trips up so many jazz players – from this one issue, I’ve seen so many jazz musicians think minor harmony comes from The Dorian mode instead of Natural and Harmonic Minor. Don’t let this be you! It’s a little strange, but remember…it all goes back to the chord voicing and the actual sound.

Why understanding minor harmony matters

We’ve gone over a lot today, so let’s take a minute to digest everything…

From where minor comes from, to issues with dominant and Tonic minor, there is a lot to understand for a complete picture of minor harmony.

Use the diagram below to see all the relationships we’ve talked about and how everything fits together into the framework of minor harmony in jazz:

There’s a BIG difference between theory used as shortcuts to play jazz and theory used to gain a deeper understanding from a compositional and structural standpoint – today, we did the latter.

You see, music theory alone will not make you a great musician, but it can help you understand the how and why of chord progressions. And in turn, this understanding will help you figure out how to utilize your jazz language over these progressions more effectively.

In learning anything, understanding the WHY behind something is crucial…

I’m not one of those people who does well with shortcuts or someone telling me, “just do this and don’t worry about why.”

I need to know why.

And what I’ve found is that if you understand the why behind something, you can do whatever it is you’re trying to do, much better.

It often goes like this though…when you first learn something, you’re acquiring new information so fast, that you don’t really care about the why, or even have the skills to truly understand it, so you just gather information, which is great…

But as time goes on, if you don’t go back and fill in these gaps in your learning, the shortcomings will eventually rise to the surface.

While today’s lesson gets into some pretty tedious music theory, understanding it will help you HEAR BETTER. It will help you PLAY BETTER , COMPOSE BETTER , and help you make better sense of just about anything having to do with minor.

And at first it may not even be obvious to you how the information helps you…but the bottom line is this: A better understanding of minor harmony will lead you to better results with the countless tunes and progressions in minor.

Some of the things we talked about today get confusing really fast…so to help you with this, here’s a list of some of the takeaways that I hope you get…

Essential Minor Harmony Takeaways:

- The Relative relationship of major and minor – A relative minor key lies a minor 3rd below (or a major 6th above) the root of a major key. For example, A minor is the relative minor of C major. And, C major is the relative major of A minor.

- What a minor key means – The Natural Minor is what people mean when they refer to “a minor key.” For instance, “The key of A minor” means the key of A Natural Minor. This is why “The key of C major” and “The key of A minor” both have no sharps or flats.

- Why there are multiple names for Natural Minor – The 6th mode of a major scale is called Aeolian. It’s also the Relative Minor of the major scale it comes from, and it’s also called a Natural Minor Scale. All three of these names refer to the same scale, but from a different point of view.

- Why minor harmony starts with Natural Minor – Minor harmony starts with the Natural Minor, which naturally occurs in the major scale as the 6th mode, the Aeolian Mode. But Natural Minor harmony is incomplete because it lacks crucial chords like the V7 dominant.

- How Natural and Harmonic Minor are related – Natural Minor has a minor 7th. Changing the 7th to a major 7th, transforms the scale into a Harmonic Minor scale. This is the only difference between Natural and Harmonic Minor scales.

- Why we use harmony from both Natural and Harmonic Minor – Natural Minor alone lacks essential jazz chords, like the V7 dominant. To transform the V minor 7 chord into a V7 dominant chord, we harmonize the Harmonic Minor scale and borrow the V7 from there, meaning we replace the V minor 7 chord in the Natural Minor harmony with the V7 dominant chord from Harmonic Minor harmony.

- What Chord Borrowing means – Chord Borrowing is a music theory term that means to borrow a chord from a parallel key or scale. Parallel means that the two scales start on the same root. For example, C major and C minor are parallel.

- The common jazz formula for chords in minor – Jazz often uses the chords from Natural Minor, but borrows the V7 chord from Harmonic Minor. This is not always the case, but a pretty typical scenario.

- Why the V7 in minor is altered – The V7 chord is typically altered because the extended chord from Harmonic Minor harmony contains the b9 and b13 in the upper structures of the sound.

- Why the Tonic minor chord generally includes the natural 6th – Tonic minor chords are generally voiced with the 6th in order to distinguish the sound of the Tonic minor and make it sound more like a home base, rather than a chord that wants to move to a dominant chord like a ii minor 7 chord in a ii V I.

- Why the Tonic scale is not Natural Minor – In jazz, in a minor key, our tonic scale is not the Natural Minor. We tend to voice a Tonic minor chord with a natural 6th, which makes the Tonic scale The Dorian mode. It has nothing to do with a ii minor chord function, even though it uses the same scale-tones as Dorian.

As you make progress with this lesson, keep in mind that these are not rules to obey. They are explanations and interpretations to help your understanding as a jazz improviser, composer, and musician.

The music theory behind minor harmony may seem overwhelming, but just take it one concept at a time…

With some study, you’ll add a complete understanding of how minor harmony works in jazz to your toolbox and open up harmonic doors that never made sense to you before!!