I wish I could tell you it’s all fun. That every time you practice music is meant to be super creative, interesting, and joyful. That it never feels like you’re just working and trudging through. But the truth is, until we have devices from The Matrix that can hook up to your head and teach you Mandarin in 5 minutes, there’s no way around the countless hours of conscious repetition needed when practicing music. So for now, we can send Neo back to Hollywood and be on our jolly way to the practice room…

Everyone talks about how to practice jazz as if all you have to do is transcribe, learn tunes, and a few jazz scales…and voila!! You’re playing jazz!!

If only it were this easy and straightforward…

Of course these are all good things. Through transcribing you can learn language. Working on jazz standards is a must. And scale and theory knowledge help support and explain the concepts and sounds you’re learning.

But how does all this information actually get in your brain? And not only how does it get there, how do you have it when you need it?

This is a question I’ve asked myself many times.

If only there were a way to get information to permanently reside in my head, ready to use at any moment.

That’s exactly what we need as jazz improvisers…

The least sexy part of practicing music

When it comes to practicing music, there are a million things to tackle when playing jazz. But removing instrumental technique and sound from the equation, practicing jazz improvisation can be broken down into several different modes that you might be in when practicing:

- Discovery Mode – This is all about discovering new information. Transcribing, learning a tune, figuring out something by ear by one of your favorite musicians…these are all discovery oriented.

- Concept Mode – This has to do with your conceptual understanding based upon how you analyze and interpret information that you discover. How does Bird get to that #5 on the dominant 7 chord so eloquently? What was he thinking over that altered dominant chord?

- Drill Mode – This part of practicing music is the repetitive drilling of information, for example, when you create an exercise over a specific chord change or progression, or take a specific line and practice it over and over until you have complete mastery over it in all keys.

- Pure Improvisation Mode – This is when you solo over chord changes while not thinking about anything in particular. You’re just improvising and playing as if performing.

This is just one way to think about how things fit together when practicing, but let’s take a look at a few different practice topics and see where they might fit into this schema of the four different practice modes…

Most people spend the bulk of there practice time in the “Pure Improvisation Mode“, soloing with play-alongs over and over. Other people get hooked on transcribing or learning tunes, which are both part of “Discovery Mode”, as you’re discovering new information.

And many people live in the land of “Concept Mode,” trying to analyze and interpret what Bird or another musician was doing and boil it down into neat little concepts…

Now, all of this is great, and you should be in ALL 4 modes of practice at different times during your practice, but what do most people overlook and barely spend any time on?

Drill Mode.

The LEAST sexy part of practicing music, but the MOST important.

Why drilling information is so important to practicing jazz music

When practicing music, we have a problem that is quite unique to jazz.

I call it the “real-time” problem and it’s exactly what you might guess it is.

It’s the problem that when performing jazz, everything occurs in “real-time,” meaning there are no second chances, do-overs, or take-backs. Everything unfolds and develops in the moment.

What unfolds is a result of what you already know combined with what’s happening in the moment – the other musicians playing and how you’re interacting, the vibe, the acoustics of the room, the energy of the audience.

Where we run into problems is with the “what you already know“ part…

You see, you can transcribe all day. You can learn the changes to a jazz standard straight from the recording. You can discover and analyze jazz language. You can improvise over a jazz play along 1000 times…

But without breaking this stuff down when you’re practicing music into simple and meaningful exercises and mindfully drilling them over and over, the information will not be there when you need it.

The “Drilling” part of practice solves the biggest problem we have as jazz musicians. It implants the information we need most into our mind, yet nearly everyone avoids it. It’s really simple. If you want to be better at playing jazz, don’t avoid it.

Perhaps it’s not as fun or exciting as discovering new information…Sometimes when I’m transcribing, I feel like I’m figuring out the method to the greatest magic trick in the world. With each note I learn, I get closer to unraveling the secrets behind what makes something sound so special.

Or when I’m just soloing and playing over a standard, I get lost in the moment and remember how much I love to play the saxophone.

While these activities are very important and so central to practicing jazz, they do not deal with the most crucial problem.

The real-time problem.

Perhaps if the consequences were greater for not solving this problem, we would have greater success. What if the consequence of not being able to use, recall, manipulate, and improvise with everything we’re learning would result in physical harm?

In some activities, this actually is the case…

The “real-time problem” is not unique to jazz improvisation. In fact, many other activities have this problem, especially sports. A specific sport where this problem plays a key role is in the world of combat sports.

MMA, Muay Thai, boxing…with the rising popularity of the UFC, combat sports and their fighters have become household names. I bet you know who Connor McGregor is whether you want to or not.

So what can we learn from this violent and crazy sport?

Combat sports and practicing music are more alike than you think

Walking into a ring isn’t easy. Your heart’s pounding and you’re thinking “What did I get myself into?“

Even at the low level of Muay Thai that I compete at, it’s still a trip…

And when you’re in there, time really does slow down. You respond instinctively. The things you know the best come out and literally everything else you forget. In a flash it’s over and you’re hand is either raised or it isn’t…

It becomes very clear to you and all of those watching where you put your time in, and where you didn’t.

When you’re preparing for a fight you’re drilling something over and over because you need your body and mind to respond in a specific way for a given situation, without thinking.

Drilling something over and over creates INSTINCTUAL reactions for a given situation.

Like jazz improvisation, you use all 4 modes of practice while preparing. In training you use:

- Discovery Mode – Your coach and peers teach you new techniques. You watch video of your heroes and steal their techniques. You’re learning new ideas and variations all the time.

- Concept Mode – You mentally figure out how you can think about each technique. You conceptualize it, name it, understand it on a deep level.

- Drill Mode – You create simple exercises that focus on a specific technique and drill the exercise over and over until you’re body naturally responds the way you want it to. You build on these exercises and drill those, pushing yourself further.

- Pure Improvisation Mode – You spar with your peers, sometimes consciously using the techniques you drilled that day to reinforce them and add them to your improvisatory weapons, but remaining in the moment and improvising with what the situation at hand. You experiment and see how you can integrate the techniques and change them in real-time in response to what’s happening in the sparring session.

If you trained for a fight and spent little time in Drill Mode, you may intellectually understand things, but couldn’t actually use the techniques and knowledge in the fight. You’d be severely handicapping yourself and risk serious potential injury.

So, while the consequence of botching a chord change or not being able to play over the bridge to Have You Met Miss Jones is basically nothing in comparison, we should act as if we’re a fighter preparing for a fight.

If you actually want to improve at jazz improvisation, you need to be in “drill mode” for a lot of your practice time.

You don’t need a million jazz concepts. You don’t need that much language. You don’t need to transcribe every Bird solo. What do you need?

You need information at your immediate disposal that you can manipulate, modify, and morph in the moment to you’re liking.

It’s not fun. It’s not creative. It’s mechanical and it’s thought out, but it’s the way to actually get the information you want, into your mind.

Using Drill Mode in practicing music

It’s easy to change how you practice music to include more drilling if you keep yourself on task and know exactly what you’re practicing, when you’re practicing.

Get your music practice into Drill Mode with these 4 easy steps:

- Find something you want to work on – This could be a jazz standard, a piece of jazz language, a jazz improvisation concept or technique, or anything else you’re interested in improving. The best things to work on when practicing music are the things you are NOT good at. When in doubt, GO SMALL. For instance, If you’re working on a tune, choose 2 or 4 measures of the tune. If you’re working on major jazz language, take one piece of major jazz language. If you’re working on a concept like a diminished scale pattern, take one variation of the pattern.

- Create simple exercises which work on the problem area – Once you find your weak spots, create clear exercises around them. They can be melodic, harmonic, rhythmic, technical, motivic. But without creating a definitive exercise that attacks the area you want to work on, you won’t be effective in Drill Mode. You can combine multiple things you want to work on into ONE exercise. For example, you could combine a Charlie Parker line with a jazz standard you’re working on as we’ll illustrate later.

- Choose an amount of time for drilling the exercise in each key – It’s important to hit as many keys as possible to even out your technical and mental facility in the more difficult key centers. Depending upon how long your exercise is choose an amount of time that allows you to drill the exercise sufficiently in one key before moving on to the next. This could be 1 minute, 2 minutes, or even 5 minutes in each key if what you’re working on is quite complex. Figure out what works for you and the particular exercise.

- Set a timer and drill the exercise – It sounds like overkill, but investing in a digital timer and forcing yourself to use it will keep you on task and accountable. Even if you had all the time in the world to practice music, drilling material with a timer on your stand will greatly increase your productivity.

And remember…Don’t space out! When you’re practicing music and in drill mode especially, make all the mental, physical, and aural connections you possibly can. Know the chord-tones you’re working with, the scale fragments, the harmony. Play with the sound you want to perform with and be mindful of what you are drilling!

Now that you understand the process of how to integrate drilling into your practice, we’ll look at a few examples of how you can drill jazz language in all keys, drill jazz language over a jazz standard, and how you can drill chord-tones over standards.

But first, let’s define something we want to work on and jump into Discovery Mode for a hot second and find a line to use in the exercises we create.

Let’s work on something everyone has issues with…The Bridge to I Got Rhythm Changes.

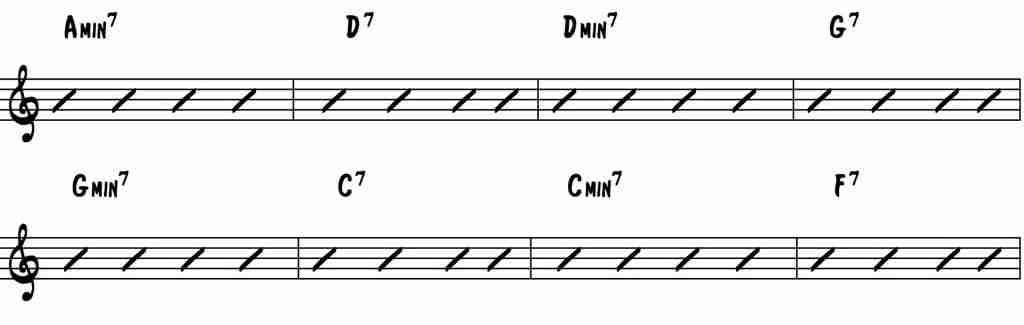

There are a million ways to think of the chords changes to Gershwin’s I Got Rhythm but for today, we’ll be thinking of them as a series of two five one progressions around the Cycle as if we were playing Rhythm Changes in the key of Bb.

This standard jazz chord progression tends to trip people up time and time again because they don’t create exercises over it and spend time in Drill Mode when they’re practicing. It’s not that difficult, but you need to isolate the problem and work on it consciously.

For these exercises, we’ll use jazz language from Charlie Parker because we’ve been talking about him so much in this jazz lesson. Listen to him play Confirmation and pay close attention to the bridge, that’s what we’re going to steal…

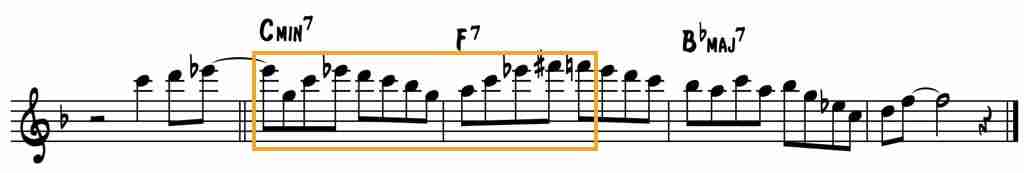

On the bridge of his solo on Confirmation, he plays this:

And we’ll be using the boxed out part of the line in our exercises.

Now, today, I did your discovery homework for you, which does you NO good. The whole point of Discover Mode in your practice is that you discover things for yourself. So keep that in mind and do your own homework. It’s not much of a discovery if someone hands it to you on a silver platter…

But, now we’ve got our chord changes that we want to work on and we’ve got a piece of jazz language over a ii V I which will help us create an exercise to drill. Let’s move on to Drill Mode…

Exercise #1 – Jazz Language Exercises In All Keys

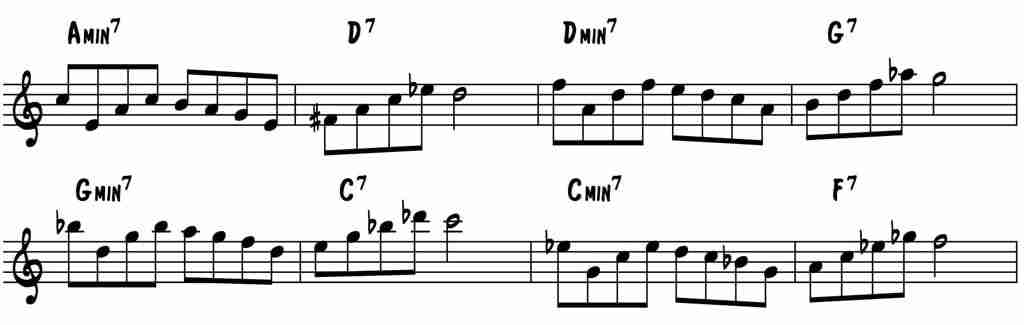

This is a very simple and straight forward exercise in theory, but many people have difficulty with it in practice. You’re simply going to play the Charlie Parker line in all keys. Make sure to refer to this lesson for pointers on playing jazz lines in all keys.

What you need: A timer, 12 minutes, and a jazz line you love

Basic Idea: Take a line through all keys

Directions:

- Set a timer for 12 minutes

- Take a jazz line like the Charlie Parker line below play it in one key over and over for a full minute with a metronome on 2 and 4. Pay attention to the chord-tones the line consists of and how they relate to the harmony. Always keep the harmony in the back of your mind. You can also alternate between playing and visualizing the line.

- After a minute is finished, go down a half step to a new key and repeat. Do this for 12 minutes, and you’ve drilled the line in all keys

Exercise #2 – Jazz Standard Exercises With Jazz Language

What you need: A timer, 24 minutes, a jazz line you love, a jazz standard

Basic Idea: Take a line and use it over a specific spot in a jazz standard.

Directions:

- Set a timer for 24 minutes

- Combine a jazz line with 4 to 8 bars of a jazz standard. In our case, we want to work on the Bridge of Rhythm Changes, which is 8 bars long. Modify the line to fit the changes however you see fit. You do not need to play the line as it originally was played.

- Then, play through the 4-8 bars using the line in the spot where the line fits harmonically. If it fits in more than one place, play it in all of those places. If it doesn’t, rest during those sections and keep the time in your mind or with a metronome. Do this for 2 minutes in each key.

Exercise #3 – Chord-Tone Exercises Over Jazz Standards

What you need: A timer, 24 minutes, two chord-tones, a jazz standard

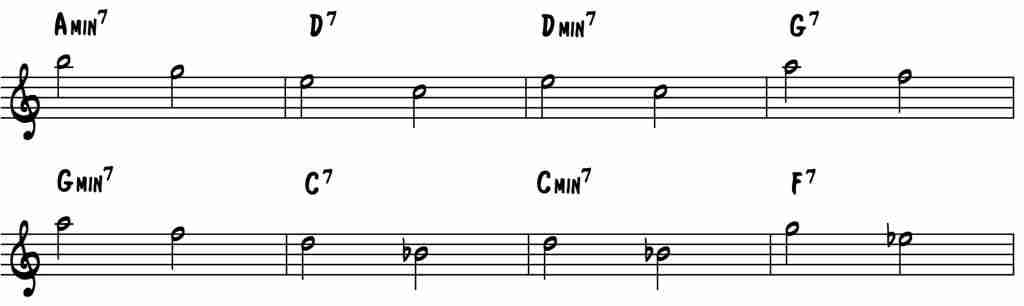

Basic Idea: Take two chord-tones and play them over the chord changes to a jazz standard.

Directions:

- Set a timer for 24 minutes

- Take a couple chord-tones like the 9th and 7th and eight bars of a jazz standard

- Then, play through the eight bars using the two chord-tones. Do this for 2 minutes in each key.

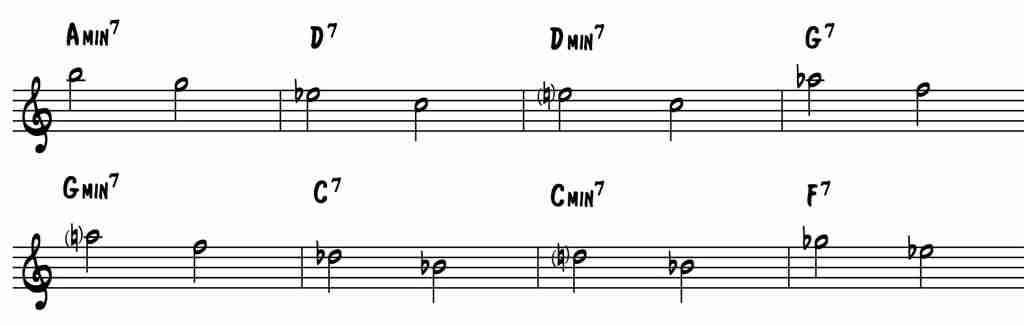

We’ll take the bridge of Rhythm Changes, thinking of a ii V for each key instead of just a dominant chord, and play 9-7 for each chord:

The exercises you can come up with are infinite! You can also BUILD on your exercises as you practice. For instance, you got 9-7 down on Rhythm Changes with a metronome on 2 and 4 at a brisk pace with no mental effort? Now, play 9-7 on the minor seventh chords and b9-7 on the dominant seventh chords.

With one little change you’ve created an effective exercise that you can practice and drill to better learn how to alter dominant seventh chords.

Introducing altered chord tones like this after you master the non-altered basic version is a great way to push yourself and take your playing to the next level.

And don’t forget about all keys. Once you can play the Bridge to Rhythm Changes easily using 9-7 in the key of Bb, Try B and the other 11.

See how an “easy” exercise becomes complex very quickly? Do not under estimate the power of simple exercises and having COMPLETE mastery over them while you practice. When you get to the more advanced variations it will become completely apparent if you truly put the time in on the fundamentals.

Remember, the process is simple to incorporate drilling into practicing music:

- Find something that you want to improve – In the last exercise it was the Bridge of Rhythm changes AND 9th and 7th chord-tones. Remember, an exercise can hit MULTIPLE weak spots.

- Create a highly relevant exercise around it – Relevant is the key word. Don’t make things difficult. Keep them simple and clear.

- Set a timer and Get in Drill Mode – This is where a large portion of your practice should be spent, where you’re drilling bits of information and pieces of jazz standards that you want to improve upon.

If you use this process, you’ll improve much more quickly than if you transcribed 100 solos, learned 100 tunes from jazz play along sets, or played a tune with a jazz backing track 100 times in a row.

You do want to transcribe. You do want to learn tunes. You do want practice just improvising. But creating exercises and DRILLING the information in an effective way is what will actually allow you to take advantage of everything you’re transcribing and learning so you can use it in real-time when you perform.

And that’s the whole point of practice.

The fastest way to get better at playing jazz

You have to practice to get better. That’s a given everyone knows. But you have to be aware of the different modes of practice and where you’re spending your time.

You should be in all 4 modes of practicing music at some point. Do you remember what they are?

- Discovery Mode – Discovering new information

- Concept Mode – How you analyze and interpret information that you discover

- Drill Mode – Repeating an exercise over a specific chord change or progression and practicing it over and over until you have complete mastery over it

- Pure Improvisation Mode – Soloing over chord changes while not thinking about anything in particular as if performing.

I bet when you do some serious introspection, you’ll find that you may be spending your time in only 1 or 2 of the modes. Hit all four and don’t skip Drill Mode. It’s by far the most ignored, but when combined with what you’re discovering through transcription, learning jazz standards, ear training, and music theory, it will yield the biggest gains.

Everything you’re learning depends on it.

When you’re wondering why you’re not getting where you want to in jazz improvisation or why a part of a jazz standard is still difficult, it’s because you haven’t spent enough time drilling exercises in these weak spots during your practice. It really is that simple.

Remember, when you’re in Drill Mode, consciously work on one thing at a time while knowing what musical problem you’re working on and exactly how you’re solving it… and last but not least…DRILL the $%^% out of it!!!!