As an aspiring musician today, you should consider yourself lucky. What I mean is, right now, you have access to more information, more resources, and more answers than any musician to come before you…

Think about it…in a few seconds you can find a recording and the sheet music to any jazz standard ever written. You can see the exact notes Miles Davis played on Kind of Blue, the lines John Coltrane used on Giant Steps, and hundreds of other famous solos.

Before you even improvise a single note you can start with a virtual library of scales, licks, and techniques cued up for every single chord you’ll encounter.

Yet, for some strange reason, becoming a great improviser hasn’t gotten any easier.

You might have noticed this with frustration in your own practice routine:

- I have a ton of resources (books, solos, masterclasses), yet for some reason I’m still not improving!

- I’m practicing scales and exercises but they aren’t translating into musical ideas in my solos…

- Why do I still have trouble hearing & memorizing tunes even though the sheet music is right in front of me?

- Why aren’t the transcribed solos I’m learning and analyzing not improving my ability to play tunes?

It makes you wonder…is this flood of easy information actually a good thing?

And more importantly, is information alone really the secret to reaching your goals as a musician??

If you’ve been frustrated with your musical progress, this is the question you should be asking yourself. And surprisingly, the answer revolves around one important piece of the way you’re learning this music…

Enter the ‘Struggle Effect’

Right now it might seem obvious to begin with all of the answers right away…

To walk into the practice room with the chords and the melody in front of you, the exact scales to play, and licks for each progression – so there’s no confusion or wasted time.

But here’s the thing that isn’t obvious, this common approach to learning music omits an essential piece of the puzzle…the process of discovery.

You see, information alone isn’t everything, especially when it comes to an art form like improvisation. Those notes, chords, scales, and theory aren’t going to change your playing – it’s the journey you take to find them.

The method you use to discover musical information will determine the skills, technique, and growth that you acquire. In fact, your learning process is the single most important factor affecting how you hear music, how you conceptualize harmony, and how you play tunes!

The trap of easy answers

Modern music education is built around streamlined information that’s handed to us on a platter – easy to digest tidbits of theory rules, sheet music, chord symbols, and scales to play over various progressions…

There’s a reason for this, it gives students an easy way to play over chords that they aren’t hearing, tunes that they don’t know, and to improvise without learning language – a short cut to the ‘right notes’ without having to develop larger musical skills.

But it comes with a cost – If you don’t have to work for information you’re not going to develop your ear, you’re not learning harmony, and you’re stuck improvising with scales.

To fix this gap you need to go back into the practice room and start finding answers for yourself – and this means embracing some struggle.

Struggle doesn’t mean despair or giving up…it means working to discover information on your own. Not taking the easy or comfortable path of looking up chords and tunes, but dealing with the sound of the music directly, patiently, and with focus and slowly building your skills.

Educators have seen the positive effects of struggle on students who aren’t given the answers right away, but are forced to work and problem solve on their own until they arrive at the answer.

And the same is true in music, the discovery process (and the time & effort it takes) is the doorway that will open up all of the other musical information and associated skills that you’re looking for!

Benefits of the ‘Struggle Effect’

- A process that allows for mistakes – Ask questions and experiment. Take a guess and try again. You’re not just finding the answer but understanding the “why” behind it and building your musicianship along the way.

- Develop real world skills – As an improviser you need to have your ears open and react to unknown situations. When you hit that “I don’t know wall” and struggle to find the answer you’re strengthening this musical “muscle.”

- Adaptability and problem solving – Working through the unknown forces you to find musical clues and be open to unexpected directions – find familiar guide posts then fill in the blanks as you go.

- Shape your musical identity – When you think, hear, and find answers for yourself you build confidence in your skills, connect and develop your inner ear and cultivate “your sound.” You are defining the music in your own way.

As we’ll show you, it’s not only OK to not know the answers or be lost as you’re learning music, it’s a vital step in your learning process as a musician.

Below we’ll look at 4 areas of your musicianship where embracing the “struggle effect” will drastically improve your musical skills and give you the results you’re looking for…

1) Learning Music by ear

The first place we encounter this ‘struggle effect’ as musicians is when the written music is taken away…

Those times when there are no notes to look at, no chords to rely on, and no key signature to help us – just you and the sound of the music.

This might happen in a lesson with your teacher, at a jam session, during a performance, or in the practice room. A situation where you’re forced to learn directly from a recording or improvise over an unfamiliar tune by ear.

At times like these it’s common to feel completely naked and freeze up. There’s nowhere to hide and your musical weaknesses are put front and center. “What is the first note of the melody, what are the chords, what is the key, what do I even play??”

This is our first test as players – where we are presented with a choice. In these situations we can either take:

1. The ‘Easy’ route:

Simply look up the information…grab a fake book, find a lead sheet, look up the chord progression, search for a transcription, find a lick to use. You play it safe and immediately get the answers, avoiding the discomfort of not knowing and being lost, but not improving.

2. The ‘Struggle’ route:

Work to find the answers yourself. What is actually happening in the music & what are you hearing? Focus on the melody and chords, break it down slowly, and work through it piece by piece. This will take more time and effort, but you’re ingraining the music and building your musicianship.

Time and again you’ll face this choice as a musician, but only one option will lead to the meaningful musical progress you want.

The path to improving your musicianship begins with your ear, dealing directly with the sound of the music. Push yourself to take in information aurally and slowly try to figure it out even if you don’t know or can’t do it at first. On the other side of this struggle are the answers you’re looking for…

Learning by ear looks different than you might expect – instead of a casual one time listen where the notes and chords are instantly revealed, it often means spending hours repeating a small section of a recording, stopping and starting until you figure it out.

This is where the “struggle” part comes in, and it’s also where you’ll make the most progress.

Ready to start your journey of learning music by ear? Want a guided method to improving your ear? Check out The Ear Training Method:

Keep in mind that you don’t have to learn everything by ear at first, especially if you’re just starting out. However, make it a point to learn one thing by ear each practice session.

It could be anything from a simple melodic line all the way to an entire tune. The more you do it, the easier it will get!

2) Building repertoire

Another important activity for any musician in the practice room is learning tunes…and one of the most effective ways to do this is directly from a recording.

The only catch is that this can be difficult to do by ear, especially when you’re starting out. As you’ve probably guessed, this is the second area where you’ll hit the “I don’t know” barrier and struggle for information.

Every tune, from Stella by Starlight to Giant Steps, presents some sort of musical challenge. This might be a single chord, a confusing harmonic progression, a line in the melody, an interval, or a chord voicing.

The way you learn the tune & overcome this challenge is directly tied to how you’ll play it! To see what I mean, let’s take a standard like Without a Song…

Again, we’re faced with two options:

(1) The Easy route – Right now you could look up a lead sheet, memorize the chord symbols, and get right to improvising…But realistically, what are you going to improvise looking at a sequence of chord symbols?

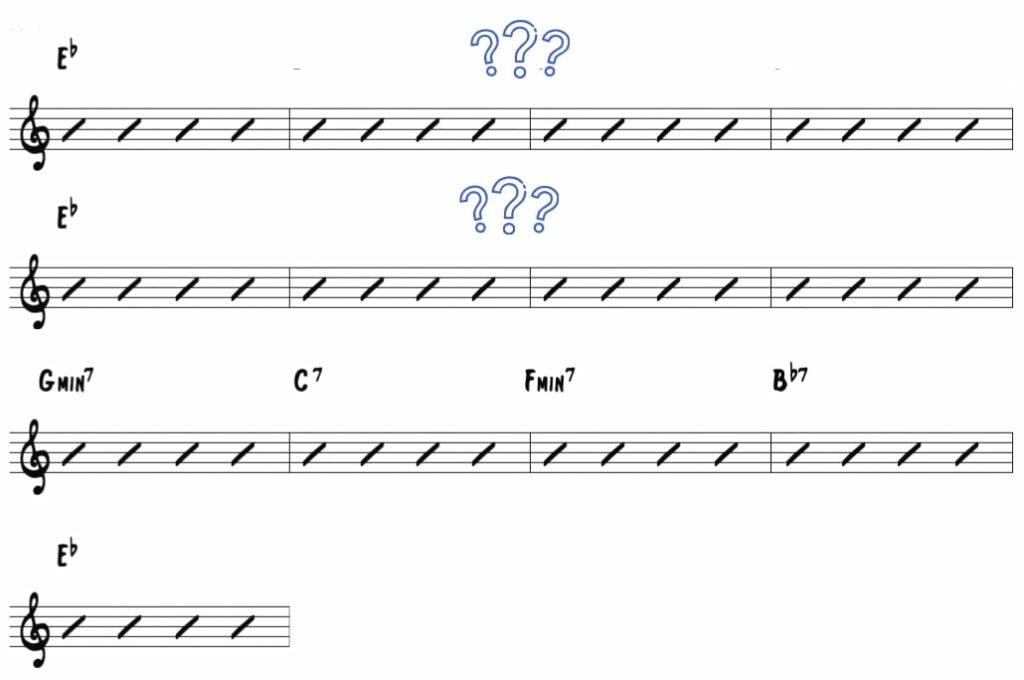

(2) The Struggle route – Now let’s explore how you might approach the tune on your own, working to find your own answers. Take the opening A section of the tune…

Using the lesson of the previous section, we’ll strive to figure it out by ear. As you repeat the sound clip a few times, listen for big musical clues:

Is the tune in major or minor? What is the meter? Any familiar chord movement? Can you identify a home key or arrival at the tonic? Any notable bass movement?

Learning a tune is never as straight forward as it seems. For example, chords are often substituted or skipped, there are different arrangements, the bass may not play the root, and progressions can change from chorus to chorus.

However, all of these details will point you in the right direction of figuring out the melody and chord progression. As you listen a bunch of times and learn the melody, you might make the following mental notes:

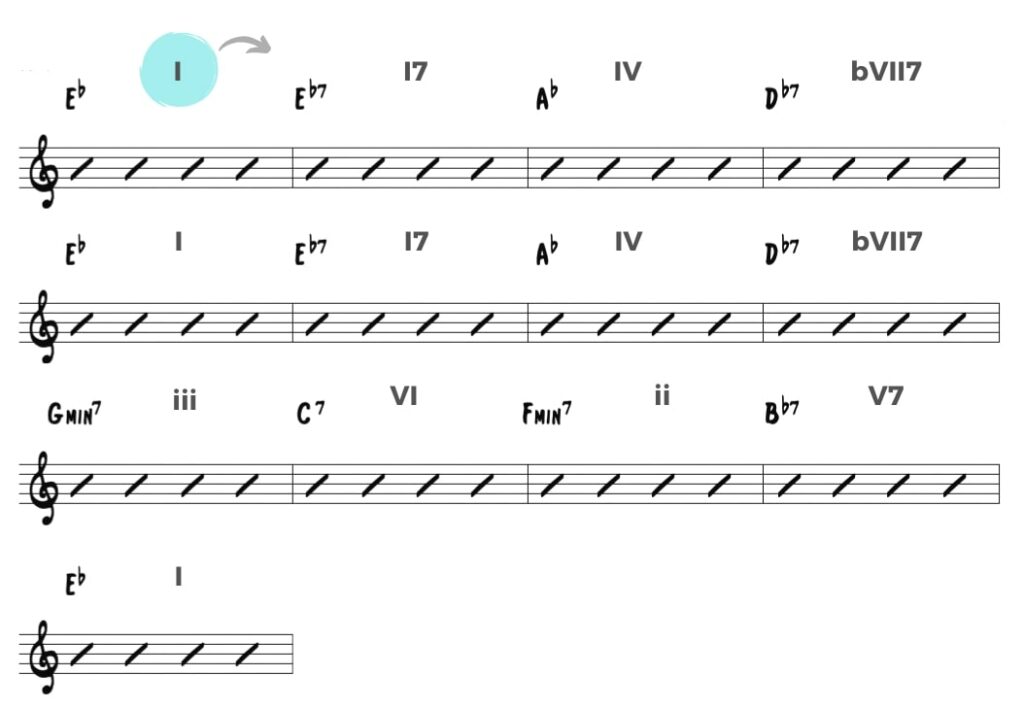

- The tune is in Major (it begins and ends with an Eb major chord)

- I hear a ii-V progression

- I recognize a iii-VI (turnaround) movement

- However, there are a few unknown chords after the initial Eb chords

Now let’s fill in those blanks. We know we start on an Eb chord and land on it again in the 5th measure, but now we need to figure out what is happening between these two spots…

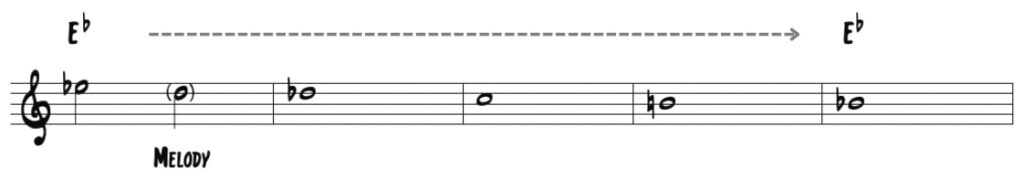

Start by focusing on any clues in the movement of the harmony or bass movement. In repeated listening, can you begin to find step-wise harmonic resolution or a guide tone line?

How do you find these notes? Play along with the recording, find the first chord, and start on different chord tones. Where do you hear the notes wanting to resolve or move next?

Another clue is to check the bass line for the root of the chords:

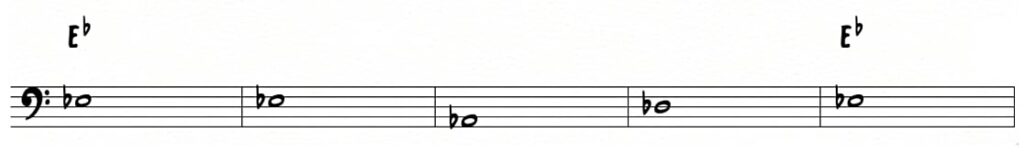

The process is like an image that starts out blurry and then slowly comes into focus with each musical clue. Putting these two lines together we can figure out those unknown chords:

At this point you’re conceptualizing the melody and harmony in terms of sound and music. You’ve gone through the process of not knowing and now you’ve ingrained the chords and melody through an “aha” moment.

These are musical skills that you can use to learn any other standard, and better yet, you are in a great position to begin improvising your own solo over this tune!

Simply by embarking on the process of figuring out a tune by ear, scanning the recording for musical clues, you’re gaining valuable insight into the melody, harmony, and song form that you won’t get from looking up the tune in a fake book.

But we’re not done yet, we have to make sense of these notes and chords and harmonies…what is the story or function of each chord in the larger form?

Specifically, how does each chord function in the larger key of Eb major?

Looking at the chords in the context of Eb Major and determining which chords are arrival or transition points, some harmonic elements that stand out are:

- The I chord moving to IV via a I7 chord

- A bVII7 chord or Backdoor ii-V in the 4th bar

- and the use of Cycle movement – I to VI to bVII

As you can see, an important part of learning tunes requires an understanding of how harmony is used in a jazz context.

Looking for a way to make sense of harmony as it’s used in the context of jazz standards? Need a process that will give you the tools you need to easily learn tunes on your own? Check out Jazz Theory Unlocked

Learning tunes is something that you’re going to be doing as long as you play an instrument. The sooner you start learning them on your own, the easier the process will become…and the better you will sound!

3) “I Don’t know what to Play”

“I don’t know what to play!” We’ve all said this as musicians at one point or another…

You encounter a chord, a progression, or a tune where you suddenly draw a blank. You’re not hearing anything and you’re lost, scrambling for something to play...

In moments like this it’s tempting to find a “quick fix.” To turn off our minds and ears and rely on someone else for the answers…looking up the chord progression or finding a scale that will alleviate this moment of confusion.

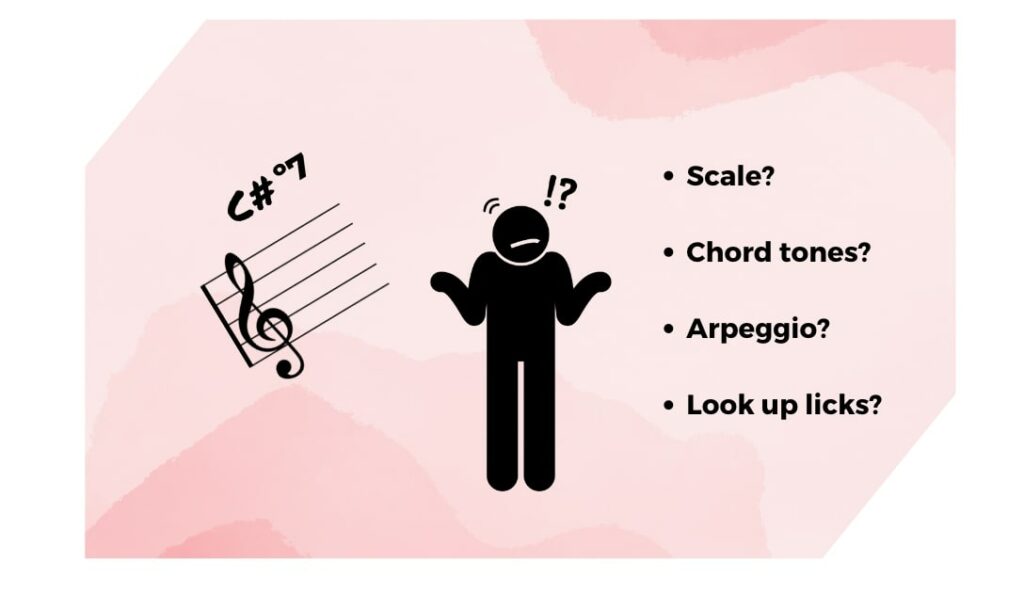

As you learn tunes and build your repertoire, this “unknown” sound that you encounter can be anything from an unexpected dominant chord to

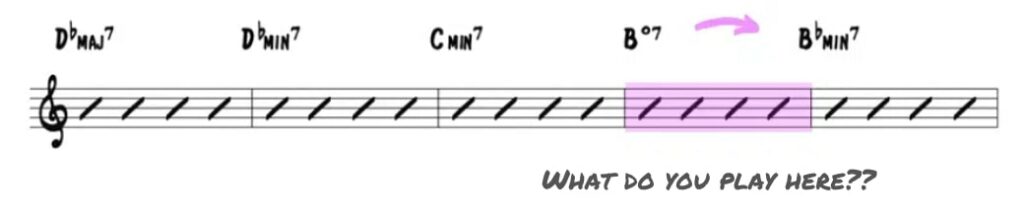

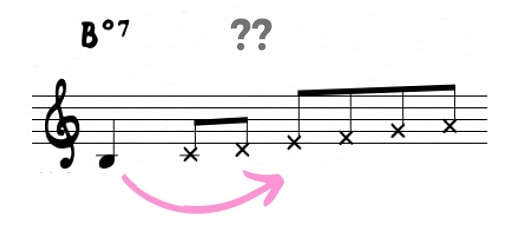

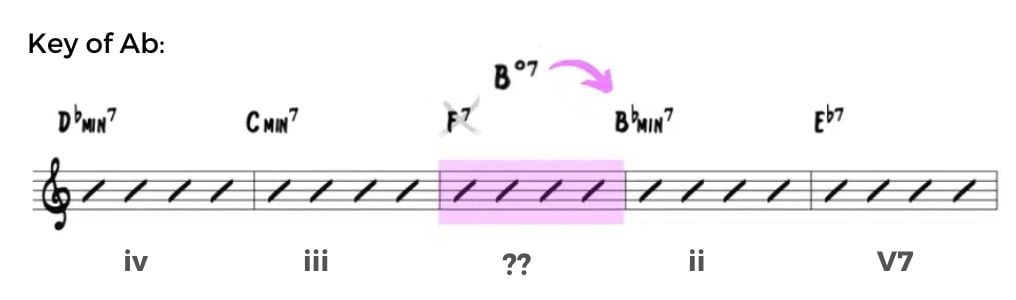

For example, let’s say you’re working on the popular standard All the Things You Are and you get stuck on the Bº chord in the last 8 bars of the tune:

A lead sheet will tell you that it’s a Bº chord. But what do you do with that? Play a scale, mess around with the chord tones, go up and down the arpeggio??

The truth is you’re still not hearing the sound, you don’t yet know the harmonic function, and you’re approaching it with theory definitions other people have given you. Rather than looking it up, now we’ll try to figure out how to find the answers yourself:

First isolate the chord or progression and ingrain the sound of it on repeat. Here’s an example of Art Tatum playing this chord:

Slow it down, repeat it, and sing along with it. What are you hearing? Which notes stick out to you? Play it on a piano and break it down note by note.

Start from the root and move up, playing along and experimenting with different notes. Which ones work and which don’t?

Some tones are obvious while others are subjective – Do they sound “right” to you?

Figuring out what to play on a chord is essentially finding your own sound. Focusing on what you are hearing, getting a deeper understanding of the sound and harmony, developing your own ideas, and crafting a personal approach to each chord type and progression.

Next, determine the function of the chord within the harmonic context or larger key of the tune. How does this chord relate to the chord before it and the chord after it – are there any chord tones that resolve by half-step?

Remember, a chord or chord type is not one size fits all. For example a D minor chord can exist in different keys and have different chord functions or chord tones depending on the tune and chord progression. Simply looking at the chord symbol or trying to apply one scale is not going to work!

Finally transcribe how great players improvise over this sound. What techniques are they using? Here’s an example from a Barry Harris solo over this chord:

Using all of these different clues you’ll begin to develop various ways of conceptualizing the sound or chord and some personal approaches to playing it, defining the sound in your own way.

The “struggle” of going through the process on your own yields a whole host of musical benefits, while the “easy” route would put you in a box of one scale or one lick.

4) Transcribing a solo

As a musician working to improve as an improviser, you’ve probably heard that transcribing solos is the best way to learn the jazz language.

However, this all sounds a lot easier than the reality you face when you sit down with a recording and try to figure it out note by note…

And this is the last area we’ll look at where the ‘struggle effect’ can make a huge difference in the benefit you get out of the entire process.

Why not just find a transcription and simply read the notes?…Well the truth is, the person that did that transcription and struggled through the process got all the musical benefit! And if you want to absorb these lines into your playing and understand the concepts behind them, you need to go to the recording and go through the process yourself.

Transcribing musical phrases and solos directly from a record can be challenging, so here are a few tips to keep in mind and make it easier:

- Break it into small sections – Transcribing doesn’t have to mean slogging through an entire solo. You can learn on one chorus, one phrase, or even one musical idea and see musical benefits.

- Slow it down – Reduce the tempo so you can easily hear each note, then over time you’ll be able to hear larger chunks of music at faster tempos.

- Sing it first – Repeat one phrase, line, or small idea until you can sing it, then try play it on your instrument.

Check out this lesson for some more tips on improving your approach to transcription – 10 Killer Tips for Transcribing Jazz Solos

Going through the transcription process

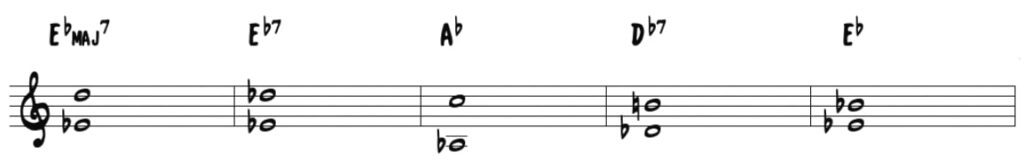

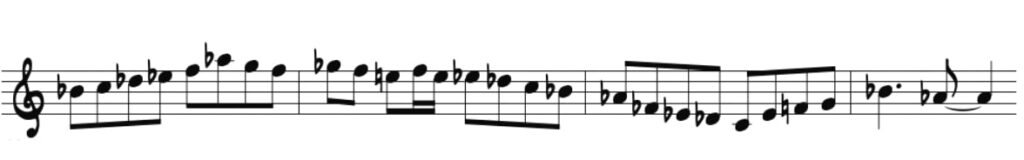

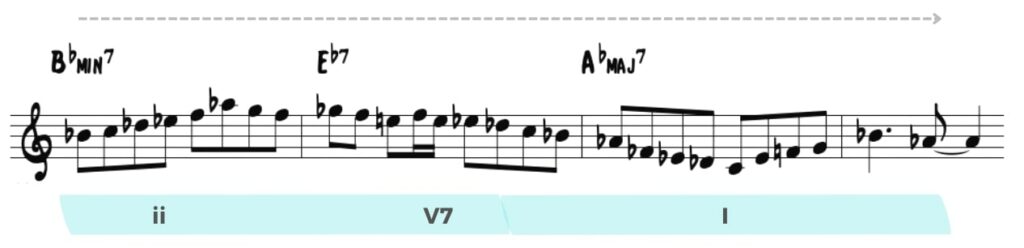

To show you what I mean, let’s take a line that you might transcribe. Here is a line from Kenny Dorham’s solo on Let’s Cool One:

Listening as many times as it takes figure out each note…this is the part that will take the time and effort. Here’s how the process might look:

- Find the first note

- Can you hear a line, phrase, scalar motion, an interval, a particular chord tone?

- Take it measure by measure or even note by note if you have to. As you improve you’ll be able to hear and learn longer phrases.

- Aim for the notes you know and then fill in the blanks. You might hear the first note, a piece in the middle or the ending. Go back and fill in the blanks, each listen will reveal more clues.

- Sing it and focus on the melody – your goal is to internalize these sounds, not just write them down!

After some work you’ll finally get the entire line:

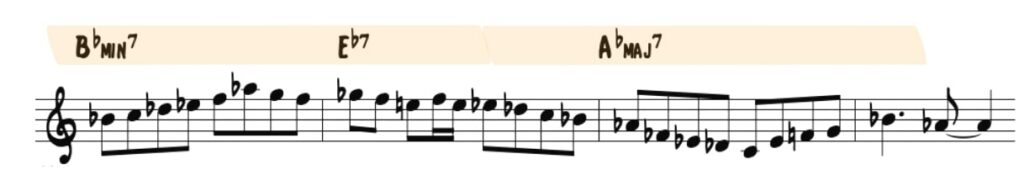

However, it’s not enough just to know the notes, you also need to understand the harmonic context as well:

In this case the line is over a ii-V-I progression in the key of Ab. You can figure this out by listening to the bass notes and the chords, and learning the overall form of the tune.

Extracting musical techniques

Next focus on the musical techniques and concepts within the line. The goal is to isolate, define, and absorb each one into your own playing.

In this Kenny Dorham line you could extract the following musical concepts:

- ii-V-I language

Focus on the entire line as a ii-V-I line to learn and apply to your own solos:

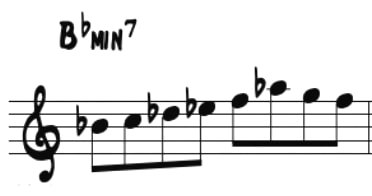

- Minor language

Isolate the first measure of the phrase as piece of minor language or ii chord techniques and learn it in all keys:

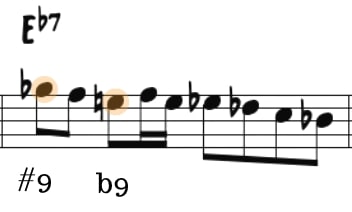

- Altered V7 techniques

Ingrain the altered dominant techniques Dorham uses on the Eb7 chord:

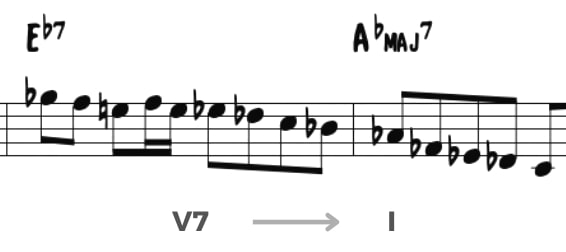

Or focus on the last two bars as an example of V7 resolving to I:

- Major language

And finally, zero in on the last measure as a Major language technique on the I chord, utilizing the b6 as a passing note:

This process can involve figuring out the notes, the harmony, writing it down and analyzing it, or it can simply happen simultaneously.

The end result of struggling through the process of figuring it out yourself is that you now know the solo or line by ear and on your instrument. You understand the harmony and now you can apply these techniques and concepts to other solos!

Easy vs. Struggle

As you can see, in the practice room you’re going to continually be faced with a decision…

You can take the easy, instant information route and mindlessly read lead sheets and apply scales…

Or you can “struggle” to build your skills, dealing directly with the music itself.

This choice will pop-up in how you listen to records, learn tunes, approach improvising over chord progressions, and transcribe solos – and the choice you make will ultimately determine your progress as a player.

Remember, the longer you avoid struggle in the learning process, the longer you are delaying your musical growth!

This doesn’t mean that you have to make your entire practice a struggle overnight however, rather strive to start incorporating some of these ideas into your practice routine.

In you next practice session:

- Learn one melody by ear

- Figure out one tune from a recording

- Learn to play over a chord without using a prescribed scale

- Or transcribe a simple line by ear and extract your own concepts

Trust me, the results will speak for themselves!